Throughout the past few years, the explosive growth of ride-hailing services such as Uber and Lyft have changed the landscape of urban transportation. Proponents of ride-hailing have long argued that these services benefit cities by reducing the need for people to own their own cars and by encourage them to use other transportation options, ultimately reducing the total vehicle miles driven in cities.

Throughout the past few years, the explosive growth of ride-hailing services such as Uber and Lyft have changed the landscape of urban transportation. Proponents of ride-hailing have long argued that these services benefit cities by reducing the need for people to own their own cars and by encourage them to use other transportation options, ultimately reducing the total vehicle miles driven in cities.

Last week, a new report by Bruce Schaller suggests that these ride hailing services are in fact, adding to overall traffic on city streets, and risk making urban cores less desirable places to live. Notably, Schaller’s report finds that:

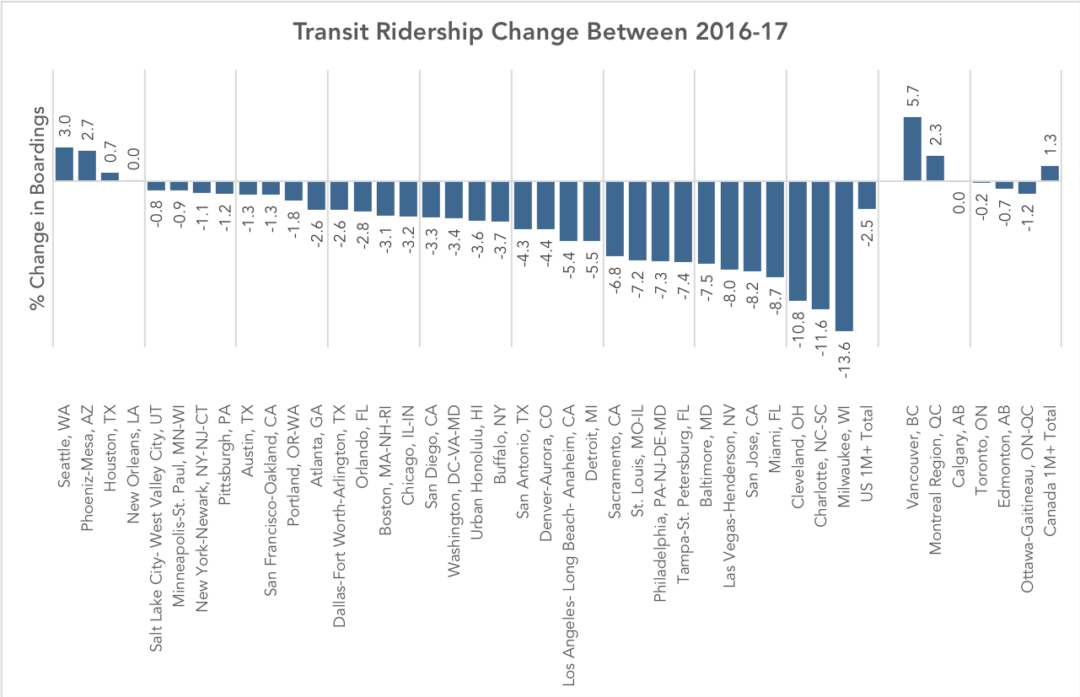

- TNCs added 5.7 billion miles of driving in the nation’s nine largest metro areas at the same time that car ownership grew more rapidly than the population.

- About 60 percent of TNC users in large, dense cities would have taken public transportation, walked, biked or not made the trip if TNCs had not been available for the trip, while 40 percent would have used their own car or a taxi.

- TNCs are not generally competitive with personal autos on the core mode-choice drivers of speed, convenience or comfort. TNCs are used instead of personal autos mainly when parking is expensive or difficult to find and to avoid drinking and driving

Schaller points out that on balance, even shared rides, offered by Lyft Line and Uber Pool, add to traffic congestion.

Shared rides add to traffic because most users switch from non-auto modes. In addition, there is added mileage between trips as drivers wait for the next dispatch and then drive to a pickup location. Finally, even in a shared ride, some of the trip involves just one passenger (e.g., between the first and second pickup).

To many readers, Schaller’s report implies that Uber and Lyft are primarily to blame for the increasing traffic congestion and declining transit ridership in many US cities. Citylab published a rebuttal to Schaller’s report, titled “If Your Car Is Stuck in Traffic, It’s Not Uber and Lyft’s Fault”. The author, Robin Chase, founder of Zipcar, disputes the scale of ride-hailing’s impacts on traffic congestion in cities. Chase writes:

[In major urban areas], taxis plus ride-hailing plus carsharing account for just 1.7 percent of miles travelled by urban dwellers, while travel by personal cars account for 86 percent.

Chase contends that traffic congestion is not a new problem in cities and that ride-hailing is no more responsible for it than the personal automobiles that still make up the majority of trips.

Special taxes, fees, and caps on ride-hailing vehicles are not the answer. My strong recommendation for cities is to make walking, biking and all shared modes of transit better and more attractive than driving alone—irrespective of the vehicle (personal car, taxi, or autonomous vehicle). Reallocate street space to reflect these goals. And start charging all vehicles for their contribution to emissions, congestion, and use of curbs.

On taxing or limiting all vehicles — called (de)congestion pricing — Chase is right on the theory and Schaller’s report doesn’t disagree. From Schaller’s report:

Some analysts argue for a more holistic approach that includes charges on all vehicle travel including personal autos, TNCs, trucks and so forth, paired with large investments to improve public transit. This is certainly an attractive vision for the future of cities and should continue to be pursued. But cordon pricing on the model of London and Stockholm has never gone very far in American cities. Vehicle mile charges have been tested in several states, but implementation seems even further from reach.

Yes, ideally, we would aim to charge every vehicle for precisely the space it takes up, for the noise it creates, and for the pollution it emits, and to vary all that by location and time-of-day. However, we have to start with what’s possible.

Ultimately, the most scarce resource in cities is physical space, so when we allow spatially-inefficient ride-hailing services to excessively grow in our densest, most urban streets, we risk strangling spatially efficient public transit and fueling a cycle of decline. If we are to defend the ability to move in cities, we have to defend transit, and that means enacting achievable, tactical policies even as we work on building the coalitions needed for bigger change. Reasonable taxes or limitations on TNCs are one such step.

Finally, these interventions should really be locally-focused, because like all urban transportation problems, this one is extremely localized. Lyft wants us to think of them as feeders to transit, which is a fine idea. But what is actually profitable to TNCs is to swarm in the densest parts of cities, increasing congestion and competing with good transit, and that’s where they do net harm. Lyft and Uber knows where every car is at every moment, so it would be perfectly possible to develop cordon-based surcharges to focus any interventions on the actual problem. Otherwise, it will be easy to say that by restricting TNCs in Manhattan we’re keeping someone in outer Queens from getting to the subway, which is not the point at all.

Christopher Yuen and Jarrett Walker