It’s been a week since Aarian Marshall at Wired published Elon Musk’s comments about public transport (“there’s like a bunch of random strangers, one of whom might be a serial killer”, etc.)

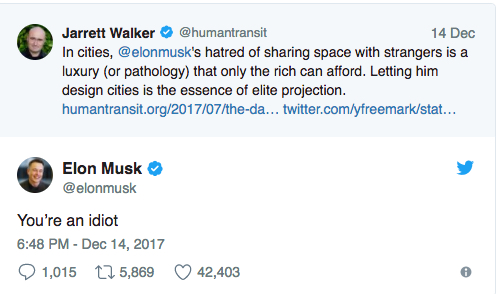

… which led to this exchange on Twitter …

… followed by a few other rude and thin-skinned tweets, all now deleted …

… which caused all kinds of unexpected things. Urban planning guru Brent Toderian launched the Twitter hashtag #GreatThingsThat HappenedOnTransit, where hundreds of people have told about great encounters with “a bunch of random strangers” on public transit; the Guardian has that story. Island Press instantly put my book on sale and sold out their inventory. And I’ve heard from hundreds of people who were offended by Musk’s comments, and by his response to mine.

Yesterday, in the Atlantic Citylab, I tried to lay out what it’s all about. Read that for the big picture. It’s much more interesting than a media roundup post!

Being called an idiot can change your life, or at least your schedule. At 6:15 AM today, a black limo appeared in front of my house and took me to a Fox Business segment with Stuart Varney. You can watch that here. And tonight I did both live and taped interviews with the BBC World Service’s Newsday program. It’s been a long day.

Now I hear Elon Musk is planning a blog post, which I look forward to.

The “Twitter war” meme … the “you won’t believe what he said!” … is really boring to me. I would much rather talk about what public transit is and why it’s so essential to great cities. At some point, I hope, Elon Musk will want to be part of that crusade. Because he’s a smart and effective guy.

Musk’s words looked really stupid from Europe. Building cities around car infrastructure is an awful idea. America sacrificed itself to show us another way.

Some of our local media are following you on twitter since the project in Yekaterinburg and they did some pieces on this as well. We’ve tried to steer the conversation to what’s really the point here away from name-calling. The media is very predictable unfortunately but in a few cases we’ve succeeded.

Clearly Musk is defensive here. It may be the “elite projection” or it may be the suggestion that his vision fails geometrically. Because he is defensive he is not taking the time to listen and/or think things through,

While he is a member of “the elite” and while Jarrett is calling out the errors of his lines of thought re transit, Musk is taking it as a personal attack rather than an intellectual disagreement. That and because he thinks Jarrett thinks he doesn’t understand geometry in general, he thinks Jarrett is calling him the equivalent of an “idiot” who does not know what geometry is.

A defensive person who thinks he is being called an idiot will lash out calling the caller an idiot.

Sadly this exchange is diminishing Musk’s reputation. He should be a natural ally. That he no longer has the luxury of time to think things through means he can’t take the time to evaluate who are experts he can trust and who are not. He is stuck in a hole here and cannot dig himself out, only in deeper. He needs to cut his loses and quit taking hits he does not need to take.

It is very likely that without realizing it Musk is a regular semi-public transit user. He surely has occasion to ride an elevator with strangers. But who knows, perhaps not.

On the positive side Musk’s loss is raising Jarrett’s stature. Although stature raising is usually itself subject to diminishing returns,

Excellent analysis Jeff.

I’m trying to make sense of the CityLab piece you authored. There, you write that “to be elite is to be a minority,” and that it would be wrong to assume that everyone shares Mr. Musk’s “tastes and priorities” with respect to “individualized transport, that goes where you want, when you want.”

But is that really true?

U.S. public transit mode share is something like 5% on average, nationwide. Even across the pond, in Great Britain, public transit mode share is 10% by number of trips and 15% by total passenger-miles covered. Desiring — and successfully obtaining! — individualized transport, that goes where you want when you want, is what the vast majority of people do, day in and day out.

So — please explain to me again how that puts someone in the elite minority.

And that’s not the only problem; there are numerous questionable statements in that piece. Here’s another: “Big cities don’t function without transit.” Really? Tell that to Houston, Phoenix, Miami, Dallas, Indianapolis, Hartford, Providence, Cleveland, Milwaukee, Cincinnati, Las Vegas, Memphis, St. Louis, Orlando and many others, each of which operates on a transit mode share of less than the 5% national average.

None of these facts could possibly be unknown to you — they come from basic government and U.S. census publications. Yet you baldly made statements that flatly contradict them.

Mass transit surely has its place in certain trophy cities like New York, London, San Francisco, Tokyo, and many others. But the world is a lot bigger than a few particular megacities, and you know it. The whole article was really disappointing and seemingly full of deliberate falsehoods.

Hey, Ben. Thanks for the comment.

First of all, national mode shares are meaningless. The US is an especially low density country, with most people living in suburbs, so of course it’s very car dependent. That says nothing about the needs or demands of cities.

Second, I should have said “big dense cities.” It’s density that really drives transit demand. However, having said that, all the cities you listed are having serious debates about improving public transit. I’ve been involved with four of the cities you list, and it’s a serious issue because people can see that if they grow their city more densely, as they want to do.

Finally, remember that if San Francisco were so terrible it wouldn’t be so expensive to live there. The free market is telling us to build more dense cities, which will mean more urgency about developing good transit.

Jarrett

Hi Jarrett,

As a planner and longtime reader with a lot of respect for your work, I’ve read this kind of exchange several times in response to your ‘elite projection’ message with some frustration. I see an equivocation (or ‘motte and bailey fallacy’) in how you write for a broad audience vs. responding to critique that goes like this:

JW: “Urban transit needs X and Y to succeed; if you listen to elites who want Z, it’s not going to work!”

Commenter: “But I live in a city where 90% of people drive to work. Most people here want and get Z. How can we be an elite if we’re the vast majority?”

JW: “Well, I should clarify that I mean cities, not suburbs, and mostly I mean ‘big dense cities’.”

Next article:

JW: “Urban transit needs X and Y to succeed..!”

You’re a prolific and influential writer in this space, and I doubt this will be the last time you have an opportunity to put out this message. So here’s my challenge: lay out a clear standard by which someone can tell if your arguments apply to their city, or some other, bigger, denser place. Lay out the conditions under which your argument succeeds and fails.

I respect your concerns that Musk, Uber/Lyft, and others in the disruptive-transportation-sphere are misunderstanding and devaluing the role of transit in cities, but go far enough down the size/density curve and there clearly is a point where cities don’t meaningfully depend on transit for their viability. Musk’s comments aren’t just being heard in the Bay Area–I suspect a lot of people in small-to-mid-size cities hear him and say “yeah, that sounds about right.”

“lay out a clear standard by which someone can tell if your arguments apply to their city”

You noted how he defines the standard

“URBAN transit needs X and Y to succeed..!”

So Musk’s vision will prevail in the smaller cities and suburbs where, say, 90%-odd percent of Americans live, and your vision will (to give you the benefit of the doubt) prevail in those few really big and dense cities where 10% of Americans live.

And, by your own admission, those metropolitan coast enclaves have the highest real estate prices and are where the actual elites live… so your entire argument is turned on its head: It’s characteristic of NY or SF (and therefore “elite”) to push mass transit, while it is perfectly average and middle class to opt for individualized point-to-point transportation.

I’ll step back and be charitable: What you’re really worried about is that the top-of-the-top professional elites who find themselves stuck in big cities like NY or SF for work reasons — but who secretly wish they could commute by car like they did when they were high school seniors growing up in Fort Wayne — will push to implement Musk’s ideas where they probably won’t work well, screwing up public transit for the other residents in the region. I know the feeling — I was once a highly paid professional living and working in Manhattan, and I hated the 4/5/6 train so much I took to driving to work every day on the FDR. I wised up an eventually left the NY metro area.

I guess this could be a problem, but it seems like a pretty niche one: It really only affects a handful of cities across the nation. Musk still has the vast majority of the market figured out far better than you do.

Mr Musk, to me, seems to be a 21st century Thomas Edison. Part clever guy, part huckster. I wonder if TAE had a swarm of fanboys that defended anything he ever said, no matter how inane, the way EM does?

Of course, unlike Edison, Musk invented the electric car and space travel, so maybe I shouldn’t use him as a comparison.

Seems to.me that Musk has the private-sector version of Nobelitis, i.e., the delusion that his exceptional skills in some areas automatically transfer to every other intellectual endeavour. The dominant “disruption” rhetoric of SV doesn’t help; you can see it in the tone-deaf way coder/engineer types talk about reinventing education or solving the homelessness crisis in SF.

Citylab article: “This means that if you decide not to ride transit because it’s too crowded, somebody else will be happy to take your place there, delivering the same level of efficiency. So the only definition of “overcrowding” that matters is the one that prevails in the culture at large—the one that determines how much personal space people will give up to fit another person on board.”

The first sentence implies something different from the second sentence. If there are enough passengers that some are left behind, then—by the first sentence—the ones who accept this level of crowding board. Thus the prevailing level of crowding is determined not by some average cultural level, but by the outlier personal tastes of the few people who are the most tolerant of crowding. Consequently, probably all passengers except the last one will experience more crowding than they would have accepted when boarding. Unless, of course, some passengers already aboard decide that it’s too crowded, alight, and wait for a later, less crowded vehicle; but I’ve never seen that happen.

A completely separate point is that cities—clusters of economic activity limited by the time it takes to commute—can be built on different methods of transportation, as demonstrated by the different “layers” of cities, American or not, that have grown up around various options. I believe the most instructive case is that of old railroad suburbs, with only walking and heavy rail. In this case, the isochrones will be a “string of pearls”, and the built area will be much the same shape.

Now imagine a walking-based city and what happens when the first commuter rail line (or streetcar) that reaches the CBD is added to it. Suddenly, a lot of land around the stations can be quickly reached by commuters. Thus some people who had previously commuted on foot decide to move from “the city” to a different part of the city, “the suburbs”. As such, the supply of land-within-specific-isochrone is greatly increased by the new line, depressing its price, and welcoming people to use it less efficiently. This has the perhaps regrettable effect of stopping the densification of “the city”, because it is more expensive to add units by demolishing an existing 2-story building and replacing it with a 4-story one than it is to build a 2-story building on a vacant lot around some station.

Furthermore, the land just around the line’s stations will see enormous pedestrian traffic (because all commuters from that “pearl” can only access the line at that station). This makes it perfect for shops. The same land is also reachable from very large parts of the city, thus is also a prime spot for offices. And, for that matter, dense residential buildings. However, to some degree all of this comes at the expense of the old parts of city, because the sudden glut of land and floorspace as well as competition from the shops adjacent to stations will depress values.

All of the above are equivalent to what happens around motorways that penetrate into the city. As long as they are uncongested and untolled, and cheap subsidized parking is provided in the city, they increase the supply of reachable land enormously. The depressed price of land invites inefficient uses. The limited number of motorway access points see a huge quantity of drive-by traffic, thus attract malls and office parks. And because they are in the same metropolitan area—economically, city—the value of land and floorspace in the central city drops.

In some way, it could be said that cars with subsidized motorways open up enough space (large area within isochrones) that using said space inefficiently is not a geometric problem if the entire city (metro region) is built around the car. There are “only” economic, social and environmental problems with having to subsidize the motorways, the parking, the costs of mandatory car ownership, the pollution, etc.—and a geometric problem if/when we have a non-auto-based compact city and lots of residents try to go into it by car.

Personally, I’m fully on the side of transit-based, necessarily walkable urbanism. Yet it must be acknowledged that even if the highways suddenly evaporated, and cars could only travel on streets, they would be faster than either buses or streetcars running in mixed traffic; and the faster lines with separate RoW (whether at grade, below or above) cannot run everywhere. As a result, there will always be some land that’s reachable only by car. And even if they have to pay for the actual costs—the market value of the land used for parking, rather than it being provided for free by the municipal government, the construction costs of motorways—there will be many upper-middle-class households that could afford that. And being only a small part of the population, it’s geometrically feasible for them to drive into the cities.

However, this vision is politically unsellable. To admit that some mode of transportation basically should be used by only one “class” is heresy. Thus we get visions with only one mode used by everyone, economics be damned. Whether that’s the “carfree” visions of either bike advocates, transit advocates, New Urbanists, etc., or the motorheads’ vision that is unusable by anything beside a car doesn’t particularly matter. And while I’m not one of them, I must admit that the motorhead vision of the city spread wide and low is at least geometrically and economically coherent, however undesirable. That is in contrast to the completely carfree visions, which are desirable but not coherent.

Personally I embrace the problem, my vision is a “low-car”, but not carfree city. Decreasing car use is a goal, but driving it to zero is not. And the key move is to destroy—ideally; realistically, at the very least, toll—urban motorways, and/or their frequent suburban access points. This would cut away large parts of the land currently within the isochrones-by-car. If the metro area isn’t already so screwed up that the malls and suburban office parks have more activity than the CBD, then uses will start to move back into the city—if the zoning allows that.

Seems like the elitism is yours in regards to your opinions. If you are so knowledgeable about transportation, why do you confuse Musk’s goals? Do you understand the difference between the needs in a dense city like NY or in Europe and the majority of car centered cities in the US? Do you understand the cost differences between building a subway and the proposed Boring Co. Tunnels? See, I don’t believe you do. There is a reason that alternative modes of transportation are being studied. Cost, capacity and automation are the 3 holy grails that these tech companies are targeting. Each has pros/cons for sure but could readily be net positives for different cities and between them. Maybe take some time to read more in depth, understand the numbers involved and the vision of the engineers. I for one very much understand the amalgam of changes coming will afford betterment of transportation. And being shoved into a subway can be fine, but 4000 public/private vehicles moving at 150mph in cheap tunnels wins in most US cities. Trolling Musk is pretty stupid BTW.