It’s “microtransit week” at Human Transit. Last weekend I asked if microtransit is a new idea and whether this matters. I’ve also explored the question of whether apps transform the economics of transport in a fundamental way, which is an important part of the microtransit conversation.

Today, I attempt to put microtransit in the context of the goals that usually motivate transit agencies. This is all part of my attempt to figure out what advice I should be giving transit agencies, all of whom are being encouraged to do microtransit pilots. Your comments will affect how I think about this, and what I advise transit agencies to do on this issue.

What is a transit agency trying to do? What goals animate its activity and justify its use of public funds? In my career I’ve watched many planning processes that seemed to dodge those questions. Over and over, I watched people try to define goals backward from projects (“what goal will make this cool thing I want look like a good idea?”) rather than forward from things that taxpayers and citizens actually care about. My book Human Transit grew from that problem.

So let’s try working forward from typical transit goals, and see where we end up on the microtransit question.

Sorting Out Goals

Transit is expected to do many things. These things generally fall into one of two opposite groups of goals.

- Ridership goals are met when a transit agency achieves maximum ridership for its budget. Ridership goals include emissions reduction, congestion relief, reduced subsidy per passenger, support for dense urban redevelopment. Ridership goals also mean that the transit agency is offering useful and liberating service to the greatest possible number of people.

- Coverage goals are met when a transit agency meets people’s needs or expectations even though low ridership is the predictable result. Coverage goals include social service goals that assess people based on how badly they need something rather than how many of them there are. Coverage goals include political equity — the desire that every electoral district or municipality gets a little something. Finally, coverage goals can be associated with agendas of upward redistribution: Intentionally low-ridership service may be run because people who benefit have the influence to force the transit agency to do it.

The goals fall into these two categories because the kind of network you’d run is totally different in the two cases. If you want ridership, you run big buses and trains offering frequent services in places with high demand. If you want coverage, you spread service out so that everyone gets a little bit, even though it’s much less attractive. I explain why this is in more detail here. My original Journal of Transport Geography paper introducing the ridership coverage tradeoff is here.

In my work with transit agencies, I encourage them to be conscious of which kinds of goal they are pursuing. I advise transit agency boards to adopt a clear policy about how their operating budget should be divided between these goals. For example, our much-discussed Houston redesign began with a Board decision to shift the agency’s priorities from 55% ridership to 80% ridership, which meant cutting their investment in coverage from 45% of their budget to 20%.

Note the reality I’m working in here: Transit agencies have limited budgets. I often hear dreamy talk about how microtransit isn’t in competition with fixed routes. “It’s not an either-or,” people say. “They can all work together.” Well, they may not be competing for customers, but they are competing for funds. When a transit agency invests in microtransit subsidies, it is doing this instead of running more fixed route service. That’s the frame in which we must understand these microtransit proposals, at least the proposals being put forward now.

Microtransit is a Coverage Tool, not a Ridership Tool

In that context, microtransit is another way of providing coverage service. Look at the numbers:

| Service Type | Typical Passenger trips/service hour |

| Urban subway | >200 |

| Urban light rail | >100 |

| Urban frequent bus | 40-100 |

| Ridership-justified suburban bus | 15-40 |

| Coverage-justified suburban bus | 10-15 |

| General Public Dial-a-Ride | 0-3 |

| Microtransit Pilots to Date | 0-3 |

| Paratransit (senior-disabled) | 0-2 |

The “service hour” is a unit of operating cost. We measure transit by the hour, not by the mile, because pre-automation transit operating costs are mostly labor. So this table corresponds roughly to “bang for buck” for public investment. (Can you make labor cheaper pre-automation? Read on.)

The last four rows in this table are services that would not exist if the only goal were ridership. (Paratransit would be provided only as required by law, not in excess of that.) If you run those services, it can only be for a coverage goal, where low ridership is the expectation.

So, it is absurd to claim that investing in microtransit is a way to combat declining transit ridership. In any transit agency, there is a place where an hour of fixed route bus service could attract 10-100 times as many passengers than an hour of microtransit could do. If you want ridership, you’ll invest more in that bus service, not in microtransit or any other low-ridership service.

Comparing Microtransit to Dismal Fixed Routes

Now, suppose we do have a coverage goal. We’re talking about a low-density, unwalkable suburban area where ridership expectations are low for whatever service we might offer. If the goal were ridership we wouldn’t serve this area at all.

In most agencies, the worst-performing suburban fixed routes typically pick up about 10 people for every hour a bus operates. Even in the context of coverage goals, those routes are hard to defend.

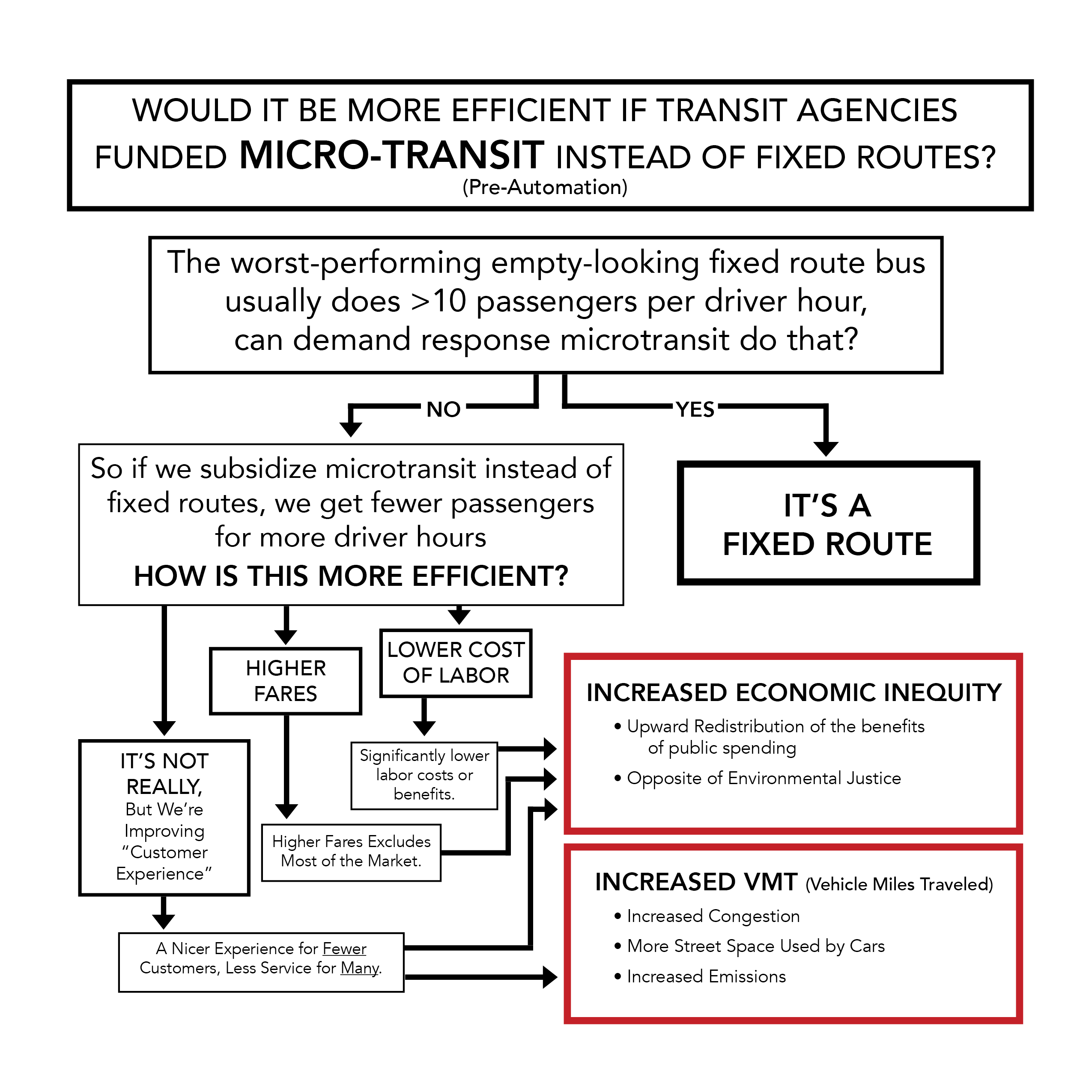

So given a coverage goal, which is the opposite of a ridership goal, the thought process for whether to invest in microtransit might look like this.

Let’s start at the top.

Flexible routing is always inefficient compared to fixed routes. You don’t really need data, although there’s plenty, to understand this geometric point.

On a fixed route, passengers gather a bus stop, so that the bus can run in a reasonably straight line that many people will find reasonably direct. This saves the bus and driver time, so the bus can get to more potential passengers, and take them to more useful destinations, in each hour it operates..

On flexible service — including microtransit — the transit vehicle meanders to serve various points where people have requested it. This inevitably leads to more driving for fewer customers than a fixed route.

There is simply no way that a flexible-route service is going to pick up 10 people per hour of operation in a low-density suburban setting. Maybe you can do it in the middle of San Francisco, but that’s not what we’re talking about here. The places where fixed route buses do only 10 boardings/hour usually have low density, long average distances, and circuitous street patterns, all of which are bad for demand-responsive service too.

So if it’s anywhere near the 10 boardings/hour of a dismal fixed route, it’s a fixed route. (There are exceptions that prove the rule. Some “deviated fixed routes” are almost entirely fixed except for a few flexible segments. Where these are productive, it always turns out that the fixed portion of the route is the source of the productivity.)

So even if your goal is coverage, why would you run microtransit instead of a fixed route? Since microtransit is reliably worse than fixed routes in passengers per service hour, what other kind of efficiency would make up for that, and make this viable?

The flowchart shows the three possible answers:

- Reduce labor cost. Forget “savings from smaller vehicles.” Operating cost is mostly labor. TNCs have certainly plumbed the depths of driver compensation, which lead, of course, to increased economic inequality and thence to a host of other ills. (You also, to a large degree, get what you pay for in terms of professional skill.) But even if those impacts are OK with you, there’s just not that much here. Suppose you cut labor costs 50% from typical transit pay scales, which is the very bottom. Now, to match a fixed route doing 10 boardings/hour, you need to do 5 boardings/hour, still far higher than what we’re seeing in any microtransit pilots. (And even all you do is match the performance of a terrible fixed route, what have you acheived?)

- Higher Fares. Of course microtransit can run on its own in a for-profit model, along the lines of UberPool. In addition, it’s possible for transit agency subsidies to reduce microtransit fares somewhat below usual TNC levels without bringing them down to anywhere near transit fares; this is being tried in some places. But this can also be a dramatic upward redistribution: more subsidy is going to people who can likely afford TNC fares anyway. There are also possibilities to subsidize TNCs for disadvantaged persons, but transit agencies have limited room (practically and legally) to discriminate in these ways. Those kinds of subsidies would better come out of social service agencies.

- “Improving Customer Experience” Who can argue with that? But the question is: Whose experience, at whose expense? If transit agencies spend more money to serve fewer people, as microtransit requires, in order to give those fewer people an improved customer experience, well, why are those people so special? “Improved customer experience” sounds great, but transit agencies are in the mass transit business, so their customer service improvements need to scale to benefit large numbers of people. If they benefit only a fortunate few, this is pretty much the definition of upward distribution of the benefits of public spending, and hence increased economic inequality. (It can also expose transit agencies to all kinds of civil rights and environmental justice challenges, both political and legal.) In short, the “customer experience” talk seems to boil down to elite projection.

All this time, I’ve been talking pre-automation. Does automation, whenever it’s really ready, blow all this away? Yes, you can erase the “increased economic inequality” box from the chart, but the “increased VMT” is still there. Because as always, if we’re putting people in more small vehicles instead of fewer large ones, we’re increasing Vehicle Miles Travelled, which means we’re increasing congestion and seizing more street space for the use of motor vehicles. Suburbs may be fine with that, but most big cities are not. There isn’t room.

So Why Would a Transit Agency Invest in a Microtransit Pilot?

Transit agencies sometimes do things that make no sense to transit professionals, because the elected officials at the top order them to do it. Right now, everyone’s talking about microtransit, so of course many elected officials are talking about it.

But in my experience working with countless elected boards and officials, it’s usually possible to steer those impulses into a conversation about goals. “When you say you want this new thing, what outcome are you really after? Are you sure this thing really does that? Have you thought through what the side effects are?” I’ve been having these conversations, about all kinds of cool-ideas-of-the-moment, for a quarter century.

At this point, I cannot come up with a logical argument from any of the commonly-cited goals of transit to the idea of investing in microtransit pilots with transit agency funds. Even if the goal is low-ridership coverage, there are vanishingly few situations where flexible routing improves on the productivity of fixed routes alone. Meanwhile, all paths in my logic lead to outcomes that most urban leaders will find bad: Increase economic inequality, both through lower wages and through the upward redistribution of benefits, and increased vehicle miles traveled. And even if you accepted those impacts, the math just doesn’t work.

(What should transit agencies do instead? Well, if the problem is ridership, look at places where ridership isn’t falling, like Seattle and Houston. Those are cities that are aggressively improving their fixed route bus systems.)

That’s a provisional opinion, which is to say that it’s a really a question. What have I missed? But please, if you’re going to comment, engage with this argument. I have heard all the beautiful stories about microtransit. What I can’t figure out are the numbers.

The last “microtransit week” post, summing up what I think we know on the subject, is here.

Instead of investing in microtransit, a transit agency can “allow” microtransit by others to serve the low density suburban coverage routes. Wouldn’t that be good for the transit agency?

Looking at case of low ridership feeder bus route looping 5km long (about 30 mins round trip) to serve a rail transit hub. Encouraging microtransit to serve one “branch” of the loop, might allow the transit agency to reshape the loop into a bidirectional route with same number of buses but double the frequencies on the stops served. Isn’t this a good goal to pursue by the transit agency?

Apologies if this doesn’t exactly address the argument you stated.

There is a tiny number of cases where this might help. But if microtransit’s productivity remains at 1/3 of that of terrible fixed routes, then even in this case a second fixed route could be cheaper.

What does “encouraging microtransit” mean? If it means not providing any subsidy, fine, though I don’t really understand how a transit agency would encourage such a thing. And if they remove a part of a route and force those people to use a TNC instead, they might run into Title VI implications because their former customers will have to pay more.

If you mean transit agencies should help subsidize microtransit, then they are putting more resources in a low-ridership area, meaning they can do less in the high-ridership area.

I don’t see why a transit agency would invest directly in micro transit service.

But it does seem that mIlicrotransit will ultimately help mass transit by reducing number of car owners on the margin, and reducing parking demand. So perhaps there is a case for transit agency to encourage micro transit in their city.

I’m not entirely convinced by microtransit either. But I think that it can be used in a way that leads to more ridership/coverage; it can gather data about (unmet?) demand that can be used to either create or refine existing fixed routes. I believe you’ve mentioned how Uber and Lyft don’t share these kinds of useful data, and they are unlikely to start. But perhaps trends, such as a previously unknown greater demand for bus service outside of peak hours, could be revealed were the data gathered publicly.

Microtransit is not the most efficient way to do this. Even if these data were a reason for microtransit to exist, the goal would be to move to more efficient forms of transit that match coverage goals.

Now that I’ve said that, I realized it was no argument at all. In fact, it is sort of an argument against it, because microtransit is trying to solve a problem that could better be solved with data.

I mostly agree with you on “microtransit”, but a few questions/observations:

In your flowchart, what if you actually do have (today) a fixed route with productivity in the 0-3 range for coverage purposes. Would your answer be simply to discontinue the route? What if retaining/serving that area is seen as a necessity (usually politics)?

What if you have a fixed route with reasonable if low productivity(~10) during the peak/day. Do you see any advantage to using “microtransit” to extend the operating hours of service in that area? Could a single microtransit service area replace multiple fixed routes after their productivity has trailed off?

To expand upon that last point:

An argument I’ve heard proposed by some as to why they don’t ride transit : fear of the unexpected. Even if transit would serve them 99% of the time (or even better than slogging through traffic, finding a parking space)

“What if my kid is sick in the middle of the day and I need to run to their school”.

“What if I need to work late/a meeting runs late and I miss the last train”

Could having a backstop of off-peak “microtransit” help to alleviate this fear, and lead to an increase in ridership on “MacroTransit” (even if they never actually use the microtransit)? Some mechanism to prevent abuse would of course be needed.

“What if my kid is sick in the middle of the day and I need to run to their school”.

Take a cab. If this happens so often that your spending on cabs outweighs your savings from taking transit, well, then I don’t know what to tell you.

“What if I need to work late/a meeting runs late and I miss the last train”

My experience living in Chicago, where a fairly high percentage of suburbanites working in the Loop take Metra, is that “Oh, man, I’m trying to catch the 5:09” worked surprisingly well to push meetings off until the next morning. Of course, the last trains to the ‘burbs were around midnight, so it wasn’t a big deal in the first place should I miss the 5:09 (or the 5:40). Sadly, I live where there is no possible way to take transit to work. *sigh*

A lot of people use concocted scenarios to avoid public transit. Let them. Planning around those corner cases is just silly. It’s like JW’s example of the elected who asked if some proposed service would get him to leave his and ride and the answer was “No, probably not”.

The problem with this argument is that microtransit would actually be LESS reliable than fixed route transit, because it is responding to unpredictable requests. If the driver is 10 minutes away from you and gets your request, s/he might have someone to drop off first, so they’ll be 10 OR 15 minutes before picking you up. And once you’re on, then someone else might have to get off (or on, or both), on your way, so you might go straight to your destination OR deviate one to three times.

Microtransit can’t be on demand straight to you and straight to your destination without being on demand for all the other riders. If it were, that’d be called a taxi (like Peter L said). And if you need to reach an ill family member, heck yeah, a taxi is worth it! But if you want more than 1 rider at a time, this trip variance gets worse and worse — you want that route to hit 10 riders per hour, it’s got up to 20 pickup/dropoff spots per hour, or one every 3 minutes on average, each of which requires at least a minute of off-path travel then another backtracking, so your trip will be very frustratingly circuitous (also more physically nauseating than a typical fairly straight bus route). And unlike for a fixed-route bus with a schedule and real-time arrival info like most cities now have, the riders on a varying route can’t align themselves to arrive for pickup in a roughly sequential path — because the route and schedule is constantly changing!

If you missed the last train, how long is this flexible route you’re looking at? If it’s”take me anywhere in the suburbs up to a train ride away, and operate till late at night” you’re gonna end up with maybe 1 rider per hour, which is again, a taxi. If a lot of people are going to the same suburb, later than the last train run, my bet is your city already has some infrequent but very reliable buses shadowing that route late into the night.

I can sympathize with this last case because I live a 15-minute walk from the transit hub of my Seattle streetcar suburb (West Seattle). It’s a bummer when I miss the last coverage-oriented rush hour bus out of downtown that stops by my house, but then I just take the all-day trunk bus route to the transit hub (terminus of the long-gone streetcar) and walk 15 minutes. Even though a bunch of other riders do the same thing, it would not be worth it for me to, say, split a cab among four of us in that 15-minute walk radius. The fourth to be dropped off would get home later than walking. The 3rd would find it to be about a wash. So they bail. And now we’ve got two people spending maybe $4 each to save 5 or 10 minutes. And unless that driver was waiting for us, we’d have to wait 5 or 10 minutes for the driver to pick us up, negating all the savings. If King County Metro wanted to serve my neighborhood better to alleviate this “missing the last bus” problem, why not just run more buses later? I’ve thought of proposing a circulating route as a last mile feeder/dropoff to/from the trunk transit hub in my neighborhood but it would just clearly be an enormous waste of money for an agency that has much higher impact spending opportunities.

“Of course microtransit can run on its own in a for-profit model, along the lines of UberPool.”

No. No it can’t. Uber fares are currently being subsidized by venture capitalists with a dream. Eventually, that dream will die (likely once it’s clear that #RoboCars are still and maybe forever in the far future) and the money will drain and Uber will be just another taxi service. Maybe.

I haven’t found (because I haven’t looked that hard) a breakdown of Uber numbers that show UberPool, their fake bus service, but I did see that they account for UberPool revenue differently than their other offerings. I’m not an accountant so I’m not clear on what that means (maybe they provide the vehicles and the drivers are on the payroll instead of being “independent contractors” that supply their own vehicle?).

The difference is lies in the published formulas for how drivers get paid. In regular old UberX, Uber takes 25% of the fare, the driver takes 75%. The driver’s share covers all the costs associated with labor and operating the vehicle, so anything Uber makes beyond its variable cost (insurance + credit card processing fees) is profit for Uber. Of course, Uber does have a bunch of fixed costs, independent of the number of rides given (lawyers, app development, driver background checks, etc.) – so they may still be losing money, overall. But, as long as the company’s cash flow per ride is positive (which, barring totally unreasonable insurance rates, it, by definition, is), UberX being a profitable enterprise is simply a matter of scaling up enough for the profits from the rides to overcome the fixed costs.

UberPool, however, is a totally different model. The company offers the customer a discounted fare, while still paying the driver 70% of what the full fare would have been had the driver been driving the same distance and time on an UberX trip. If the company is able to match enough riders together so that the cumulative fares overcome the discount, the company makes money. If it can’t (e.g. the ride goes unmatched), then we indeed have what is effectively a ride in UberX, subsidized by the venture capitalists. In theory, as UberPool becomes more and more popular, the unmatched rides will become rarer and rarer, until, eventually, the company will make money. Again, it is too early to tell if the service is inherently unprofitable, or if they are just giving large discounts for UberPool, expecting to lose money in the short term, in hopes that enough people will get into the habit of using it for the cumulative fares of multiple sharing the same ride to make the service profitable in the long term.

There is one additional category of investor-subsidized rides worth mentioning, and that’s special promotions (e.g. “50% up to 10 rides on UberX during the month of February”. These promotions are big, but likely temporary, because they’re unsustainable for the long term. One motivation might be to try to undercut Lyft and drive it out of business. Another might be to gauge how responsive ridership is to price cuts, since the “promotional coupon” price today might end up becoming the full price at some point in the future, once the human drivers are removed from the equation.

The Uber promotions are on the one hand unsustainable in the long term, but on the other hand necessary to attract drivers. The Uber fares are too low to pay drivers a market wage after accounting for the full cost of driving, like vehicle depreciation. Uber’s entire business model, supported by its marketing (“everyone needs a side hustle”), is based on drivers not noticing that they need to do all this extra car maintenance. Once drivers notice they drop out of the program, leading to very high turnover.

Thanks to the UofO online newspaper files now available, I’ve been reading the jitney controversy of a century ago in “real time.” While the war raged in Europe, the jitney craze occupied American’s urban thinkers. In The Oregonian’s articles I found the farewell speech of the manager of a Portland jitney association who showed how it was impossible to cover all costs and provide a living wage. He explained that people kept entering the market and learning this the hard way, leading to turnover and preventing his association from “stabilizing” the market. He was giving up. That was my grandfather’s generation; they are all but gone now, so now we have a generation ready to repeat the Jazz Age mistakes.

A little-noted feature of the jitney era and the current days is low-cost loans for new cars. So even if a driver takes the current cost of capital into account, they will hit a financial wall if their car wears out in a period of higher interest rates. And, if they surmount that to make a profit, some other competitor can enter the market and take a piece for themselves.

“as long as the company’s cash flow per ride is positive (which, barring totally unreasonable insurance rates, it, by definition, is)”

I’m not sure this is totally clear. Don’t they also have some variable costs for server use? It’s not at all obvious (at least to me) that these are negligible in terms of the few cents per ride that are likely profit above insurance costs.

The marginal cost of a few kilobytes of storage and bandwidth is negligible.

I’m curious how this analysis changes in an urban setting, such as with a downtown circulator intended to increase the frequency and coverage of service in a large downtown area.

Additionally, is there any positive impact to microtransit in terms of serving existing riders while also attracting new riders that would not be taking transit at all if bus was the option? In this scenario, assume the transit agency has subsidized the ride to be the same as the price of a bus trip, so as not to increase economic inequality.

“Those kinds of subsidies would better come out of social service agencies.” Do you know of places where this happens?

Yes. Australia, and I think the British-influenced world more generally. There, transport authorities deal in real costs and fares, and social service agencies subsidize the discounts.

This makes too much sense. Once you think about it, why is it the transit provider’s responsibility to allow age-based discounts? Shouldn’t the provider get the same fare for every passenger?

If society wants to provide a discount for the elderly or school-aged children, great! Schools can buy tickets for students and re-sell them to the students for a discount and elderly service agencies can do the same for seniors. Heck, give them away to their respective constituents if they want.

But why should the transit provider be penalized?

“But why should the transit provider be penalized?”

Or, to ask another way – “Why should we charge riders AT ALL at the point of entry¨?

We do not charge drivers to enter the city streets once they exit their driveways. We do not charge schoolchildren to walk thru the doors of the classroom each morning…nor should we. All public services should be free at the point of entry/engagement. That they are not (currently, in the US) is just politics.

I think that on the Continent there are similar subsidies for concession fares.

Florida’s Commission for the Transportation Disadvantaged is a social agency approach to subsidizing transportation services. http://www.fdot.gov/ctd/aboutus.htm

Also, Medicaid covers transportation costs to health care services in many states.

“TNCs have certainly plumbed the depths of driver compensation, which lead, of course, to increased economic inequality and thence to a host of other ills.”

TNCs pay as little as possible, and are exploiting pre-existing economic inequality. But if Uber replaces one job earning $18 an hour with two earning $12 an hour, is that increasing or decreasing inequality? It’s not clearly one or the other, IMO, and will depend on your perspective.

Also, you mention upward economic redistribution as something contrary to our values, but it clearly happens on a massive scale, e.g. zoning and land use policy, occupational licensing, et al.

One example in transportation is subsidies for new electric vehicles (especially Teslas), when we know new car buyers are higher income than car drivers as a whole, and even more so than society at large. (We’d likely agree it’s a bad idea, but we’re not in charge.)

I suppose you could cut this Gordian knot by requiring additional non-transit agency funding for microtransit, if you believe that transit agency spending should avoid upward redistribution.

I liked how you reduced boardings-per-hour to boardings-per-minute in your Yekaterinburg study. If it takes microtransit five minutes to detour off route, board or alight a customer, and return to the route, at most it could carry twelve people per hour. If density reduces this delay to three minutes per deviation, productivity peaks at twenty boardings per hour. (Of course, this are maximum figures)

“Flexible routing is always inefficient compared to fixed routes.”

There’s an assumption in that statement, which is what you’re missing in your analysis. Flexible routing is always inefficient compared to fixed routes….for the *transit operator*. But it is more efficient for *the customer*, who no longer has to travel to (and wait at) one of those fixed points. You can only conclude that it is *always* inefficient if you don’t take into account the efficiencies to the riders.

That’s why your efforts to find an argument leading from the goals of transit professionals to microtransit failed.

If transit agencies are only looking at *their* goals, rather than their *customers’* goals, then the operator efficiency of fixed routes is the only things that matter. It’s much easier for the agency if the customer has to devote time and resources to making things simpler for the transit operators. But efficiency for the customer also matters – it’s part of the overall calculation that riders make when they choose (or choose to avoid) transit.

This is a good point, but it requires empirical confirmation. Door to door service may, say, shave off 3 minutes at each end pre and post-ride, but only if it doesn’t on net increase trip times for everyone, from all those deviations.

Also, minutes are not all created equal. People would rather spend a minute on the bus than a minute waiting. I don’t know if people would rather spend a minute walking or sitting on the transit vehicle, for those rider deviations. We do know that people find deviations more annoying per unit of time, especially when they seem to be going in the ‘wrong’ direction.

We know TNCs and microtransit are nice for the customer, but that’s only half the case for a service. If a service doesn’t make economic sense for the operator, it’s not going to exist.

But your question related to *public* transit systems, which certainly don’t make “economic sense” for the operator (at least in the U.S., with a 30% farebox recovery rate ex NYC MTA) – yet they still exist. Microtransit doesn’t have to make economic sense in the abstract – it just has to make more economic sense than existing public transit alternatives to be a useful addition to public transit. And part of that includes the costs that *customers* have to bear in order to use public transit, since some will be willing to pay a higher fare to avoid those costs. Microtransit can save customer time, and can allow the use of much smaller vehicles (which are cheaper and more fuel efficient).

As for private providers….look, TNCs’ long-term game plan is to hope for autonomy. But there might be an intermediate stage, where they still burn money, but burn *less* money than public transit (again, with that 30% farebox recovery ratio). Such a TNC could eventually bid to replace a city’s local bus service by providing more efficient service (to the customers) for less money than the current public subsidy – the city’s still paying 70-80% of the cost of service, but stroking a check to the TNC instead of maintaining its own fleet, and the customers get better service. That’s why they’re focusing their marketing a bit on transit agencies and the politicians who fund them. They’re coming for the public subsidy dollars. As with the old joke, they don’t have to outrun the bear….they just have to outrun the transit agency.

As for Alon’s comment below, for a transit user who has close access to a *direct* bus service from start to destination, microtransit may not shave off much time. But that’s not all transit users. If you’ve got a transfer and a walk on both ends, door-to-door microtransit has a lot of room to work in to shave off travel time. A customer might have a ten minute walk to the stop, a five minute delay at the transfer, ten extra minutes of travel time due to the non-direct route from the transfer, and another five minute walk at the back end – a half-hour margin that offers plenty of wiggle room for a few detours along the way.

A TNC can only burn less money than the transit agency when it has somehow made its demand-responsive route more efficient on its end than the fixed-route transit agency service.

Or if they are able to charge a higher fare for their more convenient service. Again, the key omission in Walker’s analysis is that he focuses entirely on the efficiency to the agency, rather than including the efficient use of the customer’s time. Traditional fixed-route transit requires some customers to take on time burdens (walking to stations and transfers) to facilitate the agency’s allocation of resources. Customers have to work in order to help the provider be more efficient.

Microtransit can, in theory, take that back a bit – the service conserves *customer* time resources at the cost of being more expensive than a fixed-rate route. That can (again, in theory) allow microtransit to charge a higher fare, as customers can save time.

So if you look at *everyone* involved, microtransit *can* be more efficient – and capture some of that increased efficiency in the form of higher fares. Just looking at the *agency* in isolation doesn’t capture the whole system.

Public services have to make some economic sense too, in terms of a cost/benefit, and the benefit has to accrue to a large segment of society, in some form, to justify the taxpayer subsidy.

Sure, or the citizenry will vote out the politicians who passed the law/ordinance/regulation that implemented it. But to be fair, measurement of costs & benefits should be all-encompassing, and realistic. It would be applied equally to road building, library services, schools, armies, hospitals and all the rest of the things societies choose to spend money on. And it is (or should be) at least a 2-way street: filling a bus with riders benefits people who drive (far fewer cars competing for roadway & parking space, reduced air & water pollution, lengthened service life of private vehicles due to lowered road damage from reduced total vehicles, etc). Building roads costs all members of society – not just transit riders (less space for high-density housing, generates more private vehicle miles traveled, with all the attendant pollution, lost time, parking capacity requirements and the like, etc).

Might be fairer, more decent and just plain nicer society if we took all those sorts of measurements into account and applied them equitably (cue wistful sigh)…

If I’m the passenger, the detour works if the driver is detouring for me, but not if the driver is detouring for someone else in the car.

This is only true in certain circumstances. Alon hints at it, but your assumption is that a short walk and wait is more efficient for the rider. If you take into account deviations for other riders, the ‘efficiency’ gained by not walking and waiting can be easily erased. At this point the choice for the rider is their preference for a short walk and wait versus a longer overall trip time. There’s no clear answer on which one riders would prefer. I can say that I would prefer a shorter overall trip time and a short walk.

Whether the vehicle deviates to your front door or not, you still have to wait for it. At best, front door service might allow you to wait inside, rather than outside – but even then, that privilege comes at the cost of making the ride even slower for everybody else (because they now have to wait for you to walk to the curb).

They’re most likely inefficient for the customer as well. A fixed straightforward route is likely to be faster than a circuitous one to pick up everyone on their front door. I had several experiences in San Francisco where I had Uber discounts and was too lazy to take the bus and took an UberPool. We ended up doing long detours to pick up people and I regretted not taking the bus.

UberPool gives you very unreliable time estimates in dense urban settings. It gives you an estimate as if you were the only passenger in the car, but of course you get off-track to pick up other passengers, and it’s not unusual that your actual time in the car is double the original estimate. If you take it to a meeting, you have to take a large buffer.

Paratransit has a point: folks with mobility problems can’t easily get to the bus stops. Perhaps combining paratransit and microtransit would make sense, especially if the paratransit isn’t utilized very often.

The one benefit I see with microtransit is that it might help change people’s thinking about mass transit from “it won’t work here because (insert excuse)” to “Let’s give it a try.” Of course, we could end up with “We tried it, and it’s too expensive.”

You hit on an important point that is often overlooked. More precisely providing the general public paratransit — or microtransit lately — excuses an agency from the ADA requirement to provide a parallel paratransit service for the disabled. This saving has influenced the decision to discontinue suburban low-ridership routes — or in growth areas to never have launched regular route service in the first place.

Ridership goals are met when a transit agency achieves maximum ridership for its budget. Ridership goals include emissions reduction, congestion relief, reduced subsidy per passenger, support for dense urban redevelopment.

Microtransit connecting to HCT transit as a first mile solution is about offering another choice for getting people out of their cars and onto transit. It’s an alternative model for the park and ride. If 75% of a trip from point A to B is on transit, with 25% being on shared microtransit for first/last mile, then doesn’t that contribute to our goals to reduce emission (fewer private SOVs in use), provide congestion relief (less VMT per trip), and maximized use of subsidies (reduced capital and O&M cost of P&Rs, more efficient and lower reliance on paratransit service).

In regards to coverage, Please don’t take this as an insult or as a trolling statement, its sincerely meant as constructive feedback, but perhaps part of the issue is your sticking with traditional planning strategies and metrics to place value on a new views of an old idea? Microtransit is an old idea, but community values guide the metrics we use, and both those values and technology that influences them are changing. Perhaps we should consider adjustments to the metrics to reflect new values.

• One Person in an Uber for the entire trip is increased VMT, Uber for First/last mile only and transit on the rest, is less VMT. If those three people on the (very few) pilot projects to date, are taking high capacity transit the majority of trip, then isn’t that a win? Is it more of a win, if it is opening up P&R spaces for others? Or helping eliminate the need for them entirely?

• Claiming fixed routes are more efficient than flexible depends on your metric.

o That may only be true for the operating agency and not for the convenience of the customer. If microtransit offers improved convenience that allows transit to be more competitive with the automobile in their driveway, could more people in suburban areas choose to use transit?

o For operating hours, it’s true now, but assume automation is here and ubiquitous in 5 years. Using operating hours for automated microtransit becomes outdated. VMT becomes teh focus, and perhaps empty VMT where cars travel without passengers

o Strictly from a geometric measurement it’s also true, but you’re only measuring the one way of a two way cycle. Could Uber/Lyft/Microtransit operating in suburbs actually be more efficient if you measure empty miles traveled only. By geometric standards, buses are more efficient when inbound on the AM peak (or out on the PM peak), and are carrying the most passengers on thier route, but less efficient when traveling outbound on the AM peak (in on the PM) when they are relatively empty. For a complete fixed route cycle, the fixed route is almost always empty one way. And what about those off peak, low frequency, low ridership fixed routes that only carry 10 on the inbound? Those outbound empty miles kill its geometric efficiency

• In suburbs, microtransit shuttles operating in localized zones can dwell when not in use. It can wait for riders at the station, rather than driving from stop to stop empty, and it can optimize trips patterns to minimize VMT and maximize occupancy. Even if traveling empty in a localized zone, it may only be covering a few miles distance, versus a fixed route bus, that may travel several miles with few, if any passengers on the reverse end of its route cycle. Could one to two-mile microtransit “shuttle sheds” be developed that effectively serve stations on high capacity transit lines in the same manner as walk and bike sheds?

• If a suburbanite is using microtransit on one end, then they must be using other modes on the other end of the trip. CBDs and urban cores offer condensed and diversified mobility; Walking and bike share, much higher frequency bus and LRT service, streetcar and even car-share and ride-share. Urban centers have a lot of mobility choices and don’t NEED to rely on uber/lyft, or Microtransit shuttles on that end of the trip. Trips that start on microtransit in one suburban area, use high capacity transit, then end in another suburb on microtransit double down on benefits, and offer potentially fewer overall empty miles traveled.

JD. I don’t follow how most of these rebut my argument. I am talking about fixed route efficiency both in terms of space and in terms of labor, but mostly (pre-automation) in terms of labor. You’re not really addressing the very high cost/passenger of microtransit. Sure, it has great benefits to the ppl who use it, but why are those people so special in the context of the huge range of demands a transit agency is trying to serve?

Regarding the first mile/last mile issue.

If that is what microtransit is good for, then how should the transit agency target the subsidy? Reduced Uber fare if one end of the trip is a high-capacity transit station? Set it up similar to a transfer within the transit system?

Regarding the transit operator vs customer experience.

It seems you quickly run into conflicts between the interests of multiple users. Sure it’s nice to be picked up at your door, but what about when your van detours to drop off another passenger? As soon as you start scaling, it seems like fixed route just works better, even for the customers.

One important point about taxi-like service. As indicated in the main post, the dominant cost element is labor, which is time-based, yet the fare charged to the customer tends to be mostly distance-based. As an example, consider a 20-minute taxi ride that’s mostly on the freeway vs. a 20-minute taxi ride that’s all surface streets, with lots of stoplights. Both trips require exactly the same the amount labor (20 minutes). Both trips put similar amounts of wear and tear on the vehicle (the trip with more miles has fewer starts and stops). The former trip uses slightly more gas (maybe $1, depending on the price of gas and the fuel efficiency of the car). Yet the former trip costs far more for the customer (maybe $20 vs. $40).

What’s basically going on is that the standard taxi formula in the U.S. charges too little for the overhead of the pick-up and uses excessive mileage rates to make it up. The end result is that taxi drivers actually lose money on short trips (e.g. last mile between a suburban home and a transit station), but are willing to put up it so that they can get the occasional long trip (e.g. the person who bypasses transit completely and rides the taxi all the way between his suburban home and downtown).

If taxis were priced in way that reflected the actual cost of service (e.g. time charges pay for the driver’s time, including “deadhead” time getting to the pick-up point, mileage charges pay for the $0.535/mile cost to actually operate the vehicle), the incentives would change drastically. A “first-mile” trip between home and the transit station would cost a lot more, but once you’ve paid it, it would only be a few dollars more to dump transit altogether and ride the taxi all the way into town – in the case of a family of four traveling together, it may end up slightly cheaper to stay on the taxi than to get off and pay everyone’s bus fare. (At least that’s the case when the freeway is uncongested. If the “time” charges legitimately pay for the driver’s time, rather than mileage fees paying for time, sitting in traffic becomes very expensive; enough that getting off the taxi and onto a bus might actually save real money, at least during rush hour).

While Uber and Lyft still rely somewhat on mileage fees effectively paying for things not really related to mileage (*), this tends to be far extreme than it is for taxis. But the fact still remains that, at current rates, drivers don’t really make any money off short trips, but they put up with it in order to get that occasional long trip. (There is a reason why Uber and Lyft don’t allow a driver to know the length of a trip before accepting it; if they did, you would see a lot more drivers rejecting short trips!)

So, going back to the issue of transit subsidies for first/last mile travel. The types of trips that would be subsidized are precisely the types of trips that are *least* profitable for the driver. Even current Uber/Lyft rates may not be enough if drivers are expected to do a whole day’s worth of short trips, without that occasional long trip to give them their money’s worth.

(*) If time charges really reflected the cost of time, and mileage charges, the cost of operating the vehicle, you would see drivers largely indifferent to how long the trip is. But, if you do a Google search for Uber driver forums, you can see that drivers have a clear preference for trips in the 10-20 mile range. Short trips, there’s too little money; ultra-long trips (over 50 miles), also not ideal, because the driver has to drive too far without a paying passenger to get back.

I think it is also important to consider who is riding and the value of that ride to the individual and to society.

Compare:

* A ride by someone who has a car available for the trip and would make the trip even without transit

with

* A ride by someone who does not have a car or other convenient option available and who would not make the trip without some form for transit.

The first trip, arguably, provides less value to the individual and society than the second trip. If the trip is to/from a job, the impact is on both the individual and the employer.

So, if a microtransit service is designed to connect low-income workers to suburban jobs, it may, in fact provide similar value as the same subsidy applied to “ridership” service. (Or at least not be so out of whack as to offend your sensibilities…)

In other words, when microtransit is used as a tool to achieve specific goals in a specific context, it becomes something more than just an interchangeable transit investment. It becomes another tool in the toolbox.

John. It’s still a coverage service, even if the small number of people who benefit are low income. And surely you still have to show that microtransit is more efficient than a fixed route, which seems not to be true in most cases.

Jarrett,

Thanks for your thoughtful article. There is another dimension to equity that I feel you should include in your analysis: Total travel time. I live in San Fracisco’s Bayview district, one of the lowest income neighborhoods in the city. Many of my working-class neighbors shun public transit and spend a huge portion of their limited income on cars or Lyft/Uber fare because, as my neighbor Aaron says, “I can’t afford to spend 90 minutes getting to work”. This is especially true for off-peak and weekend travel when transit frequency plummets, the roads empty out, and car travel becomes up to 4X faster than riding the bus or streetcar.

Based on my conversations with people like Aaron, I believe that “dismal fixed route” coverage lines have poor equity because they consign riders to interminable travel times. If an on-demand or microtransit system, especially a driverless one, could significantly improve off-peak travel times while approaching the “dismal bus” in terms of cost, this would be a much more equitable outcome.

Scott, San Francisco, CA

Scott.

Microtransit is so expensive per passenger that there is no way it can be an equity solution. Extreme inefficiency means it can’t scale to meet the needs without bankrupting the transit agency. In the Bayview, you need better fixed routes.

Travel time is a key metric that we always use in our studies.

Jarrett

Yeah, this is because Muni prioritizes slow, last-resort coverage service at the expense of transit that is useful for working people. There’s no way they could afford to subsidize Lyft rides for everyone.

The problem is getting Muni to change course when you have a very participatory system with lots of “heckler’s veto” opportunities, combined with people apparently prepared to fight to their last breath rather than allow a transit-only lane in their neighborhood (see Mission Street, e.g.).

I think one could argue that paratransit which is required in the US by federal law is still a political decision to provide coverage service, but one where the local government is not allowed to choose to not provide that bit of coverage service. I think this is also a case where the letter of the ADA violates the spirit of the ADA: if you believe that frequency is freedom because it enables spontaneous trips but require paratransit users to schedule trips a day in advance, then giving that freedom for spontaneous trips only to people who do not have disabilities which force them to use paratransit is a form of discrimination.

If you’re going to argue that one person making $18/hr is less income inequality than two making $12/hr, what do you think those two people who would have made $12/hr are going to do in the one $18/hr job case, and why do you think the answer isn’t unemployment? I think income inequality is really about the people at the poorest end of the spectrum (no one should be getting upset about Elon Musk having a fortune that he can invest towards building batteries that will allow us to use power from solar panels at night, or toward reducing the pollution being breathed by people who live near freeways), and if you think jobs are the only answer, you’re once again discriminating against people with disabilities. If you care about income inequality, you should be working to get Social Security to pay a Universal Basic Income benefit of $1100/mo or more to every American over 18 rather than asking transit agencies provide less service so that they can pay higher wages.

I’d also love to see a comparison of how driver wages compare to the wages earned by their passengers; I think that would provide interesting context on whether transit employee wages are fair.

I’m a little upset about that, honestly. Why should Elon Musk or Bill Gates or Mark Zuckerberg have such a disproportionate influence on infrastructure, malaria research, or health care, respectively? Having single unelected people with so much power over entire fields is undemocratic and has real harms (ask malaria researchers how they feel about having their priorities hijacked by the Gates Foundation…).

One argument I’ve heard in favor of domestic preference/protectionist laws for transit vehicles and the like is that even if these laws increase transit agency procurement costs dramatically, the vehicle manufacturers/constructors are ultimately the political constituency that ensures transit funding keeps coming, and without them, support for increased capital spending (at least at the federal level) would be much weaker.

I wonder if a more cynical argument for subsidizing microtransit aimed at converting choice riders to transit today is that it would build support for a higher level of resources for the agency overall in the future. ‘Upwardly redistribute’ 5% of your resources today to secure a 25% increase in your overall resources tomorrow. So long as a portion of that increase goes into your mainline services, haven’t you made more people better off?

This more cynical argument is incorrect. There’s already a mode of public transit in North America that’s geared toward middle-class riders (“choice riders”) who shun more regular urban transit: commuter rail. And far from building a constituency of transit proponents, traditional North American commuter rail builds a constituency of snobs who reject any service that’s not peak-only CBD-bound commuter routes. A recent MBTA chief said “commuter rail is not public transit, it’s commuter rail.” Even the engineers get used to peak-only metrics and fight against attempts to increase off-peak frequency, e.g. in Toronto.

I’m on the same page as your argument, so I’ll pitch a micro transit scenario I don’t think I’ve seen you dismantle. It’s a fringe scenario, but I can see it being competitive in some instances:

The employee shuttle model – where everyone has the same destination (university, large employer, etc), and is approaching from a particular rapid transit stop beyond last mile reach of that destination (so for the hypotehtical users, the same origin as well). The distance of that destination is beyond walking range but also in that distance range where the local bus transfer is unappealing because of some combination of the waiting time or the short distance needed to combined with the poor route is too frustrating .

In that hypothetical, the pickup and drop off is the same for everyone, so this model beats the travel time of the flexible service which has to deviate, and it also beats the fixed route, which has to make intermediate stops along the way.

The app in this case could be used on the first leg of your trip to reserve a seat on a van from a rapid transit station bound for a particular large employer. If spots in one van fill up quickly with enough advanced warning, another van could be summoned, and so forth. The demand could be monitored to add/remove targeting the service.

I know in SAN Diego there are some bus routes which operate in Sorrento Valley from the commuter rail station to the large employment sites. Those bus routes are fixed but are very circuitous. I do not know how they perform but I would guess it’s expensive and gets poor usage.

So that’s my microtransit idea is to use the app technology to match the person to the vehicle going to their employer versus having a circuitous bus route(s) serve multiple employers on one route but takes longer for every user. It would only work in specific areas which have those characteristics.

Ride a bike. If you can’t, yell at the local municipality about protected bike lanes.

Shuttles targeted for a particular employer should be paid for by that employer. Silicon Valley companies and Microsoft outside Seattle are doing that, and I’m sure there are others/

With regard to labor costs, one of the peak periods for TNCs are on Thursday to Saturday evenings where transit service is minimally used or infrequent, required many transfers, and where there is a pool of labor willing to get compensated lower wages than they would in their day job, in exchange for the flexibility of deciding whether to work that weekend or not. I can’t turn on an app and decide to work for Target once every four weeks, or decide at 1 am that I want to go to bed instead of staying up as a shuttle driver. That’s much different than someone who is using their professional bus driving money to pay for their family’s daily expenses. Many people are willing to get paid $10 an hour (the average I am getting for late night Lyft driving, after deduction of the IRS rate and SE tax and peak hour driving bonuses) when the alternative is getting paid $0 and being unproductive.

This is one of the better arguments in favor of TNCs. Demand for taxis is highly temporal (varies by time of day and week). A fully dedicated fleet with full-time labor is therefore a lot more costly than a fleet that can be drawn at peak times from other uses (even if the other use is just sitting in someone’s garage), and a labor pool that is willing to work part-time. Of course, one might argue that the workers who reap the most benefit from such a system are those who have the luxury of being able to work as only a part-time taxi driver.

There is a huge latent pool of labor that the “sourcing” apps like takl, Uber, AirBNB, etc. are tapping into, which couldn’t be monetized in the past because even part time jobs require commitment. If you aggregate people who are able to make a commitment occasionally, but not regularly (as a retail or service industry job might) you get a good sized labor pool.

Can you provide some data or references for your values of ridership/service hour?

Back when I was a transit planner in the Milwaukee area (5+ years ago), I recall that many of the surburban bus routes serving industrial parks were in the 3-10 passengers/hour range.

I thought that the dial-ride services had higher passengers/hour than your 0-3 value. I would have estimated that number at 2-4 passengers per hour. I think that when ridership was higher they did. (City of West Bend had over 3 passengers/hour in 2013 and 2014).

Begonia. I’m sure you can find a DAR at 4 pax/hr if you look hard enough. And there are some fixed routes that survive in the 3-10 range for political reasons. But mostly the ranges hardly overlap.

One more thing to consider when you’re talking about fixed-route versus demand-response. In the United States, Federal transportation subsidies make capital investments look “cheap” when compared to operating costs.

In Wisconsin, where I worked, transit grants cover 80-90% of the cost of a new vehicle. Combined State and Federal transit subsidies only covered 45-60% of the cost of operation.

From the transit agency’s perspective then, the cost of a big, 40′ bus, which will last 10 years or more (but will only be operated by one driver) seems small when compared to the cost of 2 smaller vehicles which will likely last only 3-4 years and will be operated by 2 drivers.

Begonia, you hit on an important point. Street supervision controlling specific routes and the use of loaders at peak boarding points — common strategies before Federal capital funding — faded away, replaced by using additional buses for lowering load factors, schedule adherence or as relief buses for covering breakdowns or incidents.

“If that is what microtransit is good for, then how should the transit agency target the subsidy? Reduced Uber fare if one end of the trip is a high-capacity transit station? Set it up similar to a transfer within the transit system?”

In some areas, the problem isn’t so much the cost of riding Uber/Lyft for last-mile travel, but the fact that a deserted transit station in the outer suburbs might have no drivers around – for any price – particularly during odd hours. This results in a fear of getting stranded, which discourages people from attempting such trips to begin with (and, instead riding the Uber/Lyft all the way home from downtown since, even though it’s much more expensive, they *know* that there are going to be lots of drivers around downtown, so they won’t get stuck). A transit agency could aim to mitigate this by paying one driver $10/hour to sit around the area, waiting for rides. The customers would still cover all the actual trip fares, and if demand ever reached a point where multiple drivers are covering the area on their own, the agency subsidies can cease.

It also might make sense for an agency to subsidize the fares for paratransit-eligible customers down to the cost of riding paratransit. The per-passenger subsidy of paratransit is so insanely expensive, whatever the Uber/Lyft ride costs is bound to be less. Of course, not all paratransit customers will be able to use such a service (e.g. those that need wheelchairs), but there are some who are perfectly capable of riding in an ordinary car, but simply have a disability that prevents them from walking to a regular bus stop.

Your first idea is an interesting one. As for paratransit, that’s being tried. The problem is that working with frail people is a specialized skill that you won’t get for $10/hour, although it’s cheaper than fixed route drivers.

You make a point of discussing pre-automation situations, then pivot to automation afterwards with not much detail. It seems to me though that one would have to consider automating fixed routes as well as micro transit once automation is available.

In this case savings from automation will occur on both sides of the ledger. Moreover, automating track bound service will be easier than than bus service. Fixed routes will be easier to automate than flexible routes. Correct me if I am wrong on this but micro transit does not look that well in this way either.

Totally. We have to assume automation on both sides of the ledger.

(not traffic expert, just an IT guy here)

One thing I sometimes wonder when hearing about microtransit is if there have been trials anywhere for a fixed bus route service which “stops anywhere”.

I.e. the bus should still have a fixed timetable, should not deviate, but it could pick people at any point of the route, instead of fixed bus stops.

Yes, that’s actually how many small fixed route systems start. Then they go to fixed stops because they’re stopping too often to pick up people who are only 100 feet apart. Same way that flex routes, if they succeed, turn into fixed routes.

I think post explains pretty well why automation of transit buses is going to be politically very difficult (compared to automation of Uber and Lyft):

http://humantransit.org/2018/01/why-transit-authorities-sometimes-resist-change.html

Jarrett, there are several examples in London of very long-lasting “hail-and-ride” routes which have fixed routes but no fixed stops on certain sections, which have never felt the need to go to fixed stops. They’re coverage routes to serve low-density (by British standards, still probably pretty high by US standards) residential areas which are too far from major roads for older or disabled people to walk.

Despite my agreement with the points of the original post, I think there *might* be a business case for microtransit (to be verified empirically). Suppose we have a very low demand area, with 3-5 boardings per hour.

Scenario 1: there is a fixed-route bus already and we are considering replacing it with microtransit, with same fares. The subsidy would be roughly the same in both cases (optimistic, I know) so any advantage of microtransit hinges on the novelty effect. If potential passengers really think poorly of an existing bus service and see TNC etc as “cool”, maybe the ridership would be a bit better on microtransit that replaces a fixed route? Not sure myself if this would happen but at least I can see some potential for a better use of taxpayers’ money in this scenario.

Incidentally, there is a fairly successful example of such a transition from the pre-app age, effectively a Dial-A-Ride service with minimum 30 minutes’ notice, running since 2007 with no plans to scrap it or go back to fixed routes, details here (in Polish): http://www.mpk.krakow.pl/pl/tele-bus/jak-dziala-tele-bus/

Scenario 2: there is no service at present so the choice is whether to add a fixed-route bus or microtransit, let’s say mainly as a feeder to a mass transit line. Again, the novelty factor could suggest going for microtransit, also some internal barriers like bus and driver availability or bureaucracy could make a new fixed route difficult to get going in practice. But the key consideration here is the impact on congestion. Those 3-5 additional boardings on a bus or microtransit means 3-5 additional boardings on mass transit and 3-5 less cars on the road (assuming these people were previously driving all the way). Naturally, the extra revenue from these passengers using both the feeder and mass transit is too low to reduce the high cost of the feeder (be it a bus or microtransit). The difficult question is then how much is the city willing to spend on reducing congestion by 3-5 cars each day in each peak. Scaling it up for numerous new microtransit services across the city, we might even get 1% reduction in traffic, which would be noticeable.

The cost of this solution to the congestion issue would be undoubtedly high but it would need to be compared to alternative solutions, which could be even more expensive (e.g. major investment in transit infrastructure) or politically unacceptable (e.g. restrictions on car access to city centre).

Jarrett,

In San Francisco, I hear or read about solutions related to “microtransit” and “first-mile/last-mile” almost daily. I consider myself someone who tends to “lean into the wind” and this post answers many of my questions regarding these so-called innovations. So, thank you for your clear arguments.

My post tries to engage with two points you make in your argument: reduced labor cost (and automation) and higher fares.

What if more people would ride public transit if it was “micro” (0<=3 passengers an hour) and those people were willing to pay (i.e., no federal or local subsidy) for that service? It seems this would occur if that service provided enough convenience, reliability, and cost savings compared to driving themselves. For the following, I am making a big assumption that microtransit can meet a person's convenience and reliability needs and people are rationale economic actors.* Therefore, let's tackle the cost savings question using hypothetical scenarios in a Bay Area suburban location (daily costs in parantheses**).

Scenario A:

-person 1 owns a car. Every weekday morning, person 1 drives three miles to Dublin-Pleasanton BART station ($21.98 daily personal vehicle cost), parks their car ($3 daily), rides BART to their office near 12th Street Oakland ($4.50 x 2 trips). Weekday daily roundtrip cost = $33.98.

-person 2 owns a car and lives near person 1. Every weekday morning, person 2 takes microtransit three miles to Dublin-Pleasanton BART station ($12.94 that covers full fare x 2 trips + $19.34 daily personal vehicle cost), rides BART to their office near 12th Street ($4.50 x 2 trips). Weekday daily roundtrip cost = $54.22.

-conclusion: person 1 cost person 2 cost.

So even if this makes economic sense for an individual in any scenario, what implications would this have on the purported values and space of most jurisdictions? How many people (e.g., only elites?) can afford this service and should a public agency provide the service?

*These scenarios assume one bus with 15-mile round trip service, operating 15 miles per hour (i.e., one bus per hour); not exactly frequency freedom for person 2 (or their household) to give up their personal vehicle in scenarios B and C. Also, of course people are not rationale economic actors.

**These costs are overly simplified. Adjustments to certain assumptions could substantially change answers, although I suspect the conclusions for each scenario are similar. If you want to do that or notice I made a mistake, here they are:

-person driving daily vehicle costs: Monthly loan cost for $25k sedan of $460 (4% interest rate on five-year loan) plus monthly maintenance cost of $100 plus monthly insurance cost of $80 = daily vehicle cost of ($640/30 days) = $21.33. Six miles per day (three miles x two trips) divided by the vehicle getting 30 miles per gallon multiplied by $3.25 gas/gallon = daily gas cost of $0.65. Cost excludes terminal space for at-home parking.

-person driving occasionally daily vehicle costs same as person 1 except maintenance and insurance costs reduced by one-third for simplicity = daily vehicle cost of ($580.27/30 days) = $19.34

-both driving costs partially based on: http://newsroom.aaa.com/tag/cost-to-own-a-vehicle/

-BART parking and fare costs: bart.gov

-transit service costs: fully loaded (i.e., with benefits) operator costs of $25/hour multiplied by 12 hours a day = operator daily cost of $300. Monthly loan cost for $200k van of $3,700 (4% interest rate on five-year loan) plus monthly maintenance cost of $200 = daily vehicle cost of ($3,900/30 days) = $130. 165 miles per day (15 miles x 11 hours (operator takes four, 15-minute breaks throughout the day)) divided by the van getting 15 miles per gallon multiplied by $3.25 gas/gallon = daily gas cost of $35.75. For scenarios A & B, one could assume even cheaper labor cost (i.e., TNCs). For scenario C, I am assuming no labor cost for operating the vehicle and I did not assume a future electric van. You would still need labor to plan and manage the route, but you would need that cost in scenarios A and B as well. This also does not account for the terminal costs of storing an extra vehicle for that service during the other 12 hours of day or insurance costs.

-transit revenue = three passengers per service hour x 12 service hours = 36 passengers. In other words, person 2 is 1/18th of all passengers throughout the day.

-Full cost, assuming labor, $465.75/36 passengers = $12.94 a trip.

-Full cost, assuming no labor and automation can navigate a non-fixed route, $165.75/36 passengers = $4.60 a trip.

My Scenarios B and C were inadvertently deleted (so here all three are):

Scenario A:

-person 1 owns a car. Every weekday morning, person 1 drives three miles to Dublin-Pleasanton BART station ($21.98 daily personal vehicle cost), parks their car ($3 daily), rides BART to their office near 12th Street Oakland ($4.50 x 2 trips). Weekday daily roundtrip cost = $33.98.

-person 2 owns a car and lives near person 1. Every weekday morning, person 2 takes microtransit three miles to Dublin-Pleasanton BART station ($12.94 that covers full fare x 2 trips + $19.34 daily personal vehicle cost), rides BART to their office near 12th Street ($4.50 x 2 trips). Weekday daily roundtrip cost = $54.22.

-conclusion: person 1 cost person 2 cost.

This is embarrassing as I am not sure why Scenarios B and C are not showing up:

Scenario B:

-person 1 same as scenario A. Weekday daily roundtrip cost = $33.98.

-person 2 does not own a car and lives near person 1. Every weekday morning, person 2 takes microtransit three miles to Dublin-Pleasanton BART station ($12.94 that covers full fare x 2 trips), rides BART to their office near 12th Street ($4.50 x 2 trips). Person makes return trip home for same cost. Weekday daily roundtrip cost = $34.88.

-conclusion: person 1 cost = person 2 cost.

Scenario C

-person 1 same as scenario A and B. Weekday daily roundtrip cost = $33.98.

-person 2 same as scenario B, except microtransit one-way full fare cost is reduced because of automation ($4.60 x 2 trips), rides BART to their office near 12th Street ($4.50 x 2 trips). Weekday daily roundtrip cost = $18.20.

-conclusion: person 1 cost > person 2 cost.

A public transit agency can certainly offer microtransit at much higher fares, but this is not something they do very readily, as they have a lot of civil rights and equity obligations that make this difficult. It is more likely that a private sponsor, such as an employer, could choose to do this, especially in places like California where employee transportation is the employer’s problem.

Microtransit on calm streets can probably be automated and driverless within a few years in operational service. This is a hypothesis worth testing. Primitive, early-stage automated microtransit on quiet, low-ridership routes in the near future is a tentative but reasonable step on the development path to robo-cabs that keeps transit agencies in the game of achieving universal point-to-point service on demand as opposed to staying on a path of declining market share in surface transportation with fixed-route large vehicles. Jarrett is right that the numbers have to be forecast as workable. Bern Grush and I will explain this in our forthcoming text book, The End of Driving: Transportation Systems and Public Policy Planning for Autonomous Vehicles (Elsevier, 2018).

But in that scenario wouldn’t fixed route vehicles be automated too? In fact it would be an easier problem to solve.

I’m with CSW with this one. Any automated small-vehicle scenario needs to assume automated fixed routes, which will make fixed routes vastly more frequent and attractive.

Everyone is missing a very simple way to get more bang (rides) for our buck. It is done in most other countries. Simply reduce the total number of large 60 passenger buses carrying an average of 2 passengers per hour and use 20 passenger and 10 passenger vans as needed by demand.

It makes no since that we have so many large busses eating fuel and polluting the air wit one or 2 passengers on board. So a mix of different sizes would reduce costs and pollution dramatically.

We just need more commentary sense.

In State College, Pennsylvania, home to Penn State (and not much else) CATA is starting a study about microtransit replacing some rural fixed route service.

For example, the G route serves rural neighborhoods stretching about eight miles past the end of quarter-acre-lot and big-box-store suburbia. It has 5.3 passengers per revenue hour but that is probably raised by the higher demand stops in the developed area on the principal artery toward Penn State Campus (http://www.crcog.net/vertical/sites/%7B6AD7E2DC-ECE4-41CD-B8E1-BAC6A6336348%7D/uploads/CATA_Assessment_of_Articulated_Bus_Utilization_-_FINAL_REPORT.pdf p29).

It seems as though you are assuming demand responsive service would simply cut down on walking distances to stops, but in this case cal-de-sac developments are so long residents would never walk to the bus stop, especially with the area’s high car-ownership rate. It seems demand responsive service probably still wouldn’t make sense, but this or an even more extreme example might be closer than the examples included in the post.

Of course this example is quite specific and uncommon. CATA is able to serve such low density areas because of high student ridership to/from and around Penn State Campus (campus circulators have up to 131.4 passengers per mile – p87 of the same report). The rural area served is a relatively to extremely wealthy part of the Centre Region, so the only reason to serve it is to provide coverage since the township pays CATA to serve them. Otherwise the funds could be used for increased service on the apartment corridor trunk routes or campus circulators.