By Christopher Yuen

For the past few decades, Toronto’s King Street, a frequent transit corridor through the densest and fastest-growing parts of the city, has been increasingly choked by car traffic. Built before the age of the automobile, and running in mixed traffic as was typical with legacy streetcar systems, the 504 King streetcar’s speed has deteriorated to just about walking speed on most days during rush hour. That was until three weeks ago, when the City of Toronto launched a one-year pilot project to restrict car traffic and give transit the space it needs to move. The Globe and Mail has a great piece on the significance of this project here. Details on the project and its design are available at the City of Toronto website here.

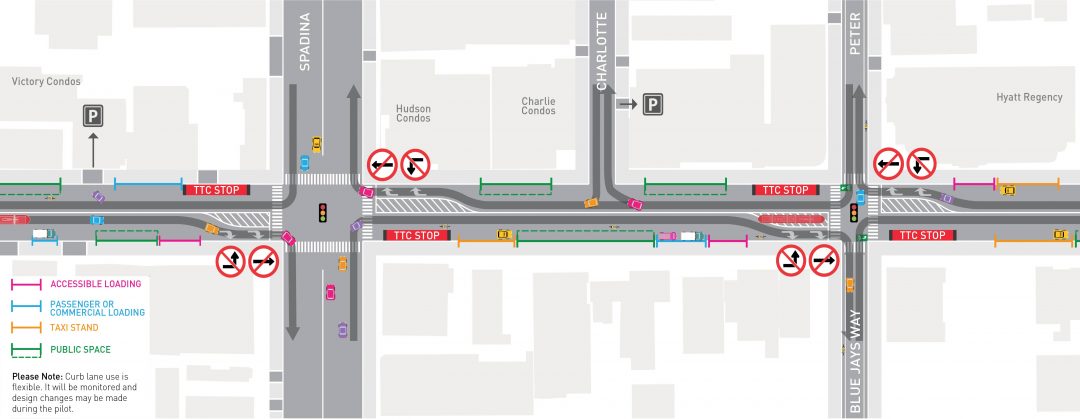

The new design of 4-lane King street was particularly thoughtful, given some of the constraints the corridor faces. While transit malls in some cities completely ban non-transit vehicles, existing high-rise parking garages that front onto King Street and businesses throughout the bustling entertainment district without back lane for loading and deliveries meant that vehicular access had to be maintained. Under the new design, left turns and through-travel are prohibited for cars and trucks at all major intersections- requiring drivers to turn right and use alternate streets.

At the approach to intersections, vehicles waiting to turn right form a queue in the right lane, out of the way of transit. At some intersections, cars receive an advance turn signal ahead of pedestrians to ensure the tail of the turning queue does not impede the streetcars.

Taken on a weekday at 4:00pm, this scene would have been much more chaotic with through-traffic blocking transit before the project. Now, cars are channeled to turn right at every intersection. (Photo: Alex Gaio)

Without through-traffic, having two lanes at the start of each block is no longer necessary, allowing for an important feature for efficient transit operations- far-side stops. Streetcar tracks in Toronto, and in many legacy systems, operate in the middle of the road. To board and alight, passengers must step into the roadway, protected only by a rule prohibiting motorists from passing open streetcar doors. As a result, stops have always been located on the near-side to reduce the risk of drivers making a right turn onto a transit corridor and immediately conflicting with passengers getting on or off a streetcar. Under the new design, streetcars stop on the far side of most intersections, beside barriers that effectively extends the curb to the second lane at the start of each intersection.

New far-side stops with a temporary curb-extension mean passengers no longer have to walk through a traffic lane to get on and off the streetcar. (Photo: Alex Gaio)

In addition to the obvious safety benefits of the new design, the far-side stops also allow transit vehicles to travel faster. Traffic signals along Toronto’s King Street already feature transit signal priority- they detect an approaching transit vehicle to hold a green light, or shorten a red light. With near-side stops, the unpredictable dwell times at stops would sometimes cause the traffic-signal to time-out, leaving the transit vehicle with a red light just as it closes its doors and is ready to get moving. Far side stops allow signals to be held for a streetcar to get through an intersection before stopping for passengers.

The new design also re-allocates curb space as loading zones, taxi stands and for new seating and patio space mid-block- all valuable features for a dense, mixed-use central business district which would not have been possible when all four lanes have been dedicated to the throughput of cars.

New public spaces like this will become especially valuable when patio season begins. (Photo: Alex Gaio)

Since its launch, public support has been for the most part, positive. The all-at-once approach to implementing this pilot across the corridor has ensured that the new inconvenience to some drivers has also been matched with a drastic, noticeable, and immediate improvement for everyone else. Across the twittersphere, Torontonians are reporting anecdotes of more consistent departures and trips taking half as they did previously.

#TTC customers have spoken! The #KingStreetPilot has improved transit for the over 65,000 daily King streetcar commuters. HT @g_meslin pic.twitter.com/NbDbtbVRVz

— Josh Colle (@JoshColle) November 20, 2017

Even among some taxi drivers, subject to the same turn restrictions throughout the day, initial skepticism appears to have eased.

My cab driver just now: ‘Did you see what they did to King Street? I thought it was going to wreck the city but now that I understand it it’s actually pretty smart.’ He has no idea but he just made my day.

— Jennifer Keesmaat (@jen_keesmaat) November 15, 2017

Preliminary analysis of GPS data shows that the project is working, significantly reducing both the average and the spread of travel times. However, it remains to be seen if enough drivers will comply with the new restrictions once the initial enforcement blitz is over. If New York or San Francisco‘s bus lanes offer any guidance, Toronto should introduce automatic camera enforcement along the corridor. Over the course of this one-year pilot project, municipal staff and the transit agency will be sure to monitor the situation closely and make adjustments based on actual results.

Cities, faced with growing populations and spatial constraints, must defend the right for transit to move if they wish to limit the negative impacts of traffic congestion. Toronto’s King Street offers a story of how that can be done quickly and effectively.

Christopher Yuen is an associate at Jarrett Walker+Associates and will be regularly contributing to this blog.