Earlier this year, the Moscow Department of Transportation asked us to help rethink the bus network in the innermost part of the city, an area about 3 km in radius centered on Red Square and the Kremlin. The first phase of this project just went into operation, so this is a good time to share some of the details of why and how a bus network redesign of this magnitude happens.

Our work was a lively collaboration with DoT staff, local consultants at Mobility in Chain (MIC) and the excellent Moscow-based geographic analysts at Urbica. As with our recent work in Yekaterinburg, I worked with local experts and DoT staff in an intensive multi-day workshop to hammer out the ideas. We also helped with some of the analysis and storytelling, and developed the main ideas of the map designs shown here.

Buses Matter in Moscow

You may be thinking: “Moscow has an extensive, highly useful Metro network. Is surface transit even a big deal?” Yes. Even in Paris, with the world’s densest metro network, an intensive subway system doesn’t eliminate the need for an excellent and celebrated surface transit network. Compared to Paris, Moscow stations are spaced more widely, and they are also famously deep, which means longer walks and escalator rides. It takes at least five minutes to move between the surface and a metro platform, or between one platform and another in a transfer station. And if you’re making a 10-15 minute trip within the core, five minutes is a very long time. Together, these factors make trips using surface modes attractive, provided that the bus and tram network is designed to take people to where they need to go.

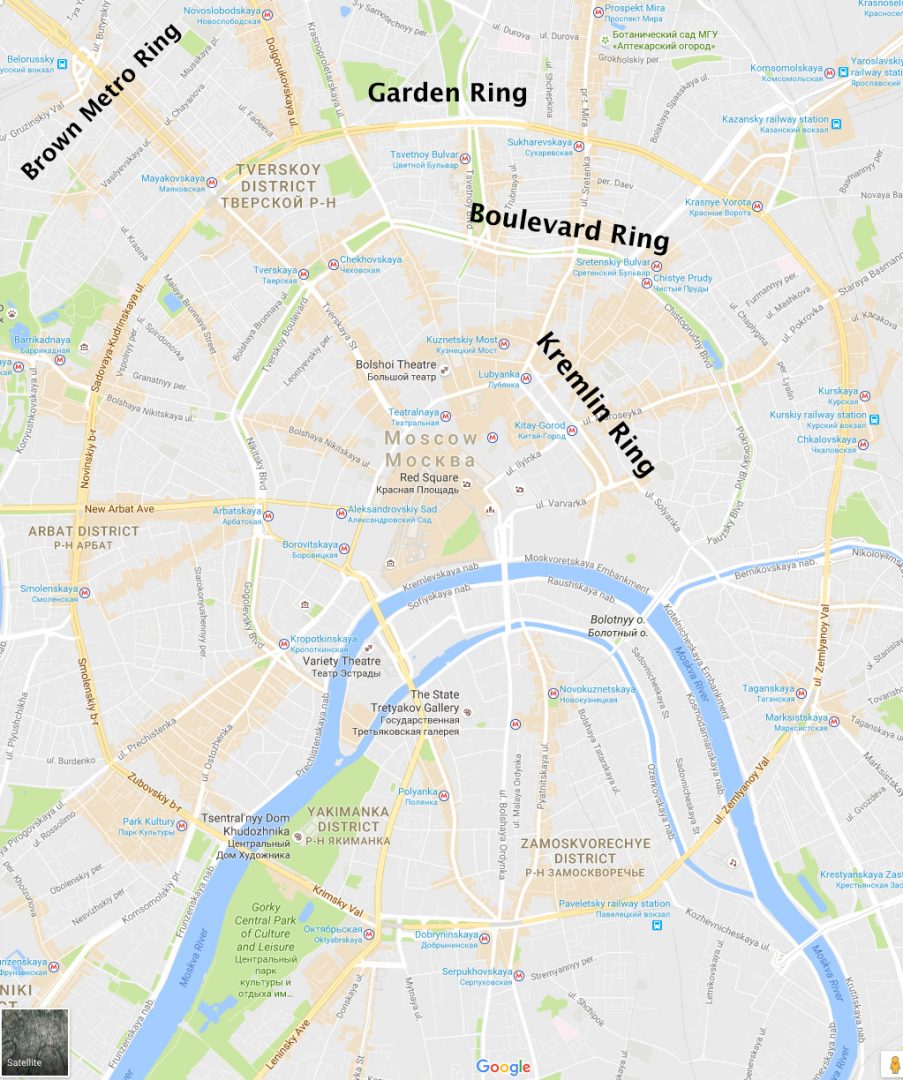

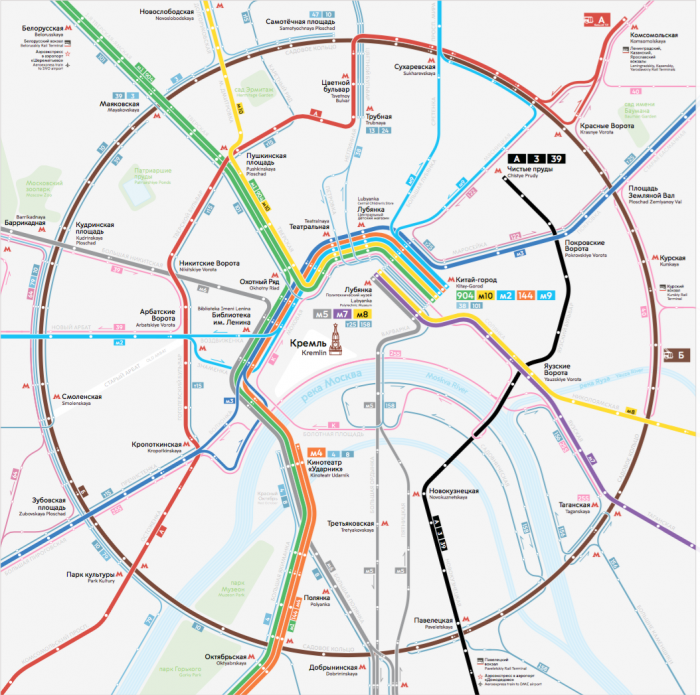

Let’s get oriented. Of all the world’s major cities, Moscow comes closest to being an absolutely regular spiderweb or polar grid. Major corridors are either concentric circles or straight radial links between these circles. This is true of the whole urban region, but for now let’s zoom into the center:

From inside to outside, we have:

- The Kremlin Ring, which orbits the Kremlin, Red Square, and world-famous citadels of religion and commerce. It’s a wide, fast street and a key stretch of it is one-way clockwise.

- The Boulevard Ring, consisting mostly of beautiful European-style boulevards with grand parks in the median.

- The Garden Ring, a very wide and fast high-speed arterial for cars, featuring many grade separations and a generally awful pedestrian environment. Memory crutch: If it has gardens, it’s not the Garden Ring.

- The Brown Metro Ring — a metro but not a street. It is outside the Garden Ring on the north and west but follows the Garden Ring in the south and east. This is the ring of intercity rail stations — just like Paris and London have — and it’s only orbital line in an otherwise radial metro network.

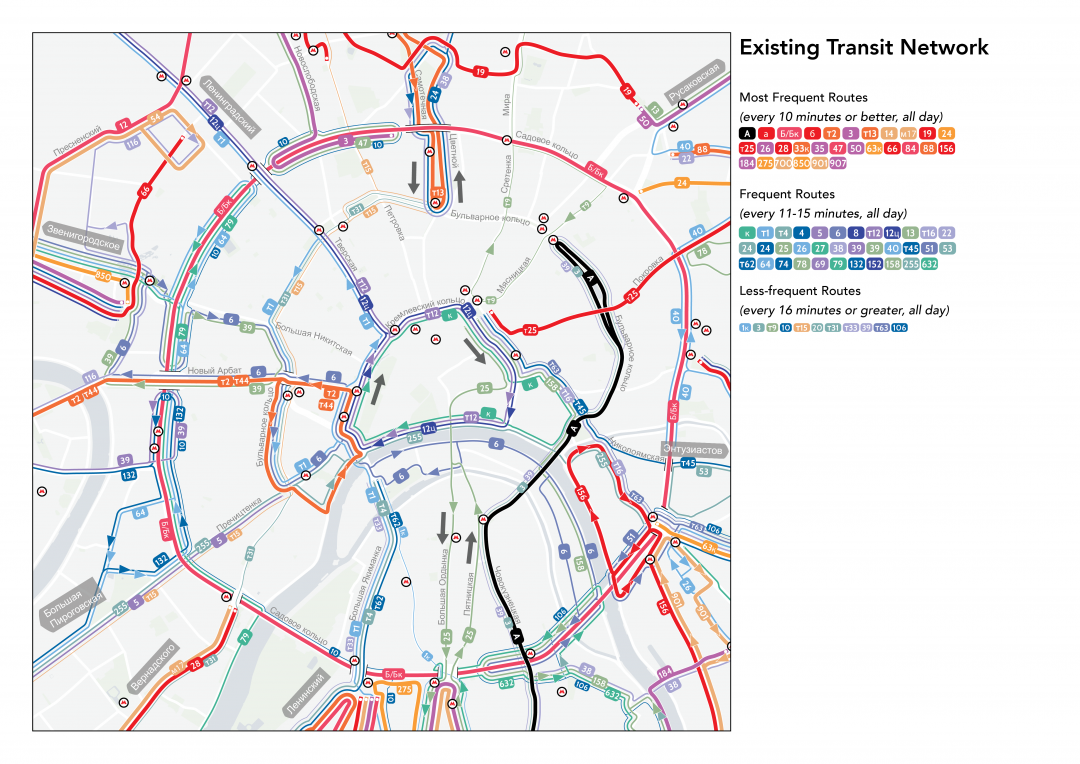

And here’s the bus network as it was until Saturday, October 8. (Download the fullsize PNG for more detail.) Wide lines in hot colors mean very high frequency. The black line is a frequent tram.

If you look closely you’ll notice several problems, apart from the staggering complexity. They all arise from the design of major streets.

Taming the Moscow Arterial

In its structure, inner Moscow is a mostly 19th century European city — reminiscent in many ways of Paris, Vienna, or Prague. It’s beautiful and very walkable, except for the major arterial streets. This is an old photo of the Garden Ring, and most of the ring still looks like this.

Garden Ring on the NW side. Old photo but typical of how most of the street looks today. Photo by https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/User:Strober

For years Moscow expanded and redesigned its major streets with the sole objective of moving as much car traffic as possible, at as high a speed as possible. (It’s routine to see cars going 80 km/hr [50 mi/hr] or more on these streets.) This goal of car traffic flow caused several decisions to be made that were bad for surface transit.

- Grade separations: The Garden Ring has numerous grade-separations with intersecting roads. These grade separations prevent transit on one street from stopping anywhere near transit stops on the intersecting street. Sometimes your bus will miss a Metro station because it’s flying over or under it, unable to stop nearby.

- Underpassages instead of crosswalks. Many of the wide, fast arterials have no crosswalks. Instead, there are occasional underpasses or bridges for pedestrians, and Metro stations also serve this purpose. This means the two sides of one of these streets are very far apart, which means the two directions of transit service are not always serving the same place.

- Forced Turns. As arterials were expanded and sped up, secondary collector streets — often walkable used by transit — were turned into “right in, right out” where they touch these arterials. This disrupted many logical bus routes that formerly ran straight across these intersections. Along the Garden Ring in the map above you’ll notice lots of local routes making U-turns and bizarre looping patterns. These are mandated by the forced turns.

- Limited Turns and One-Way Streets. As we see worldwide, when the goal is to flush cars through a city, you’ll see many one-way streets and restrictions on cross-traffic turns (i.e. left turns if you drive on the right as in Russia, right turns if you drive on the left). This forces the two directions of a transit line apart — often very far apart so that they no longer serve the same places. For example, try tracing route T1 (pale blue) from where it enters the map in the northwest. It ends up serving completely different places in the two directions, all the result of one-way streets and prohibited turns.

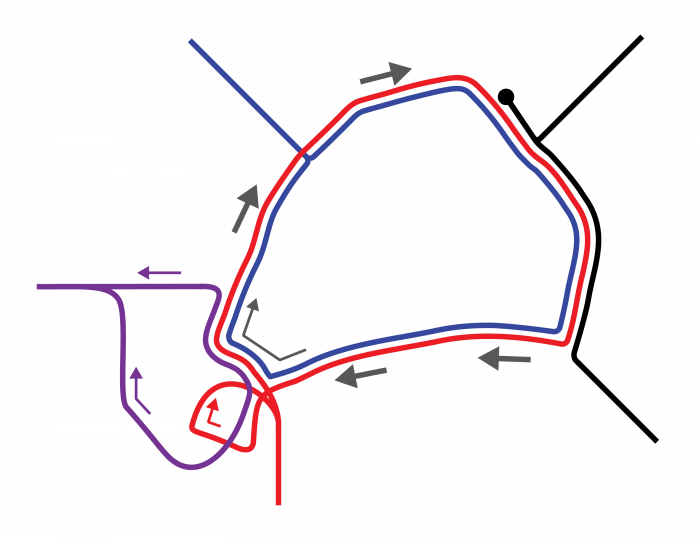

- One-way loops. Very few people want to travel in circles, but that’s what the buses have to do. At the very center of Moscow, the Kremlin Ring flows clockwise-only around the innermost core. This is the biggest obstacle to transit of all. There are no stops on the south side of the ring, which is essentially a freeway. So a two-way line flowing across this area would be able to serve the core in the eastbound direction only. Westbound it would fly nonstop past the core — missing all its major destinations and metro connections. This is why almost all existing routes have to terminate in the core rather than flow across. The entire structure of the inner city bus network was dictated by the one-way traffic pattern of the Kremlin Ring. Indeed, this diagram shows pretty much all of the things that a bus could do at the Kremlin Ring, which is not much:

Fortunately, the Kremlin Ring has just been fixed. A continuous bus lane has been built allowing buses to run two-way across all parts of the Ring. Various limited-turn and forced-turn problems are also being solved through infrastructure projects, over the next few years. (Even the Garden Ring is starting to be civilized, with help from our colleagues at Mobility in Chain.)

This changes everything, and allows for a totally new network that will be vastly more useful.

The New October 2016 Network

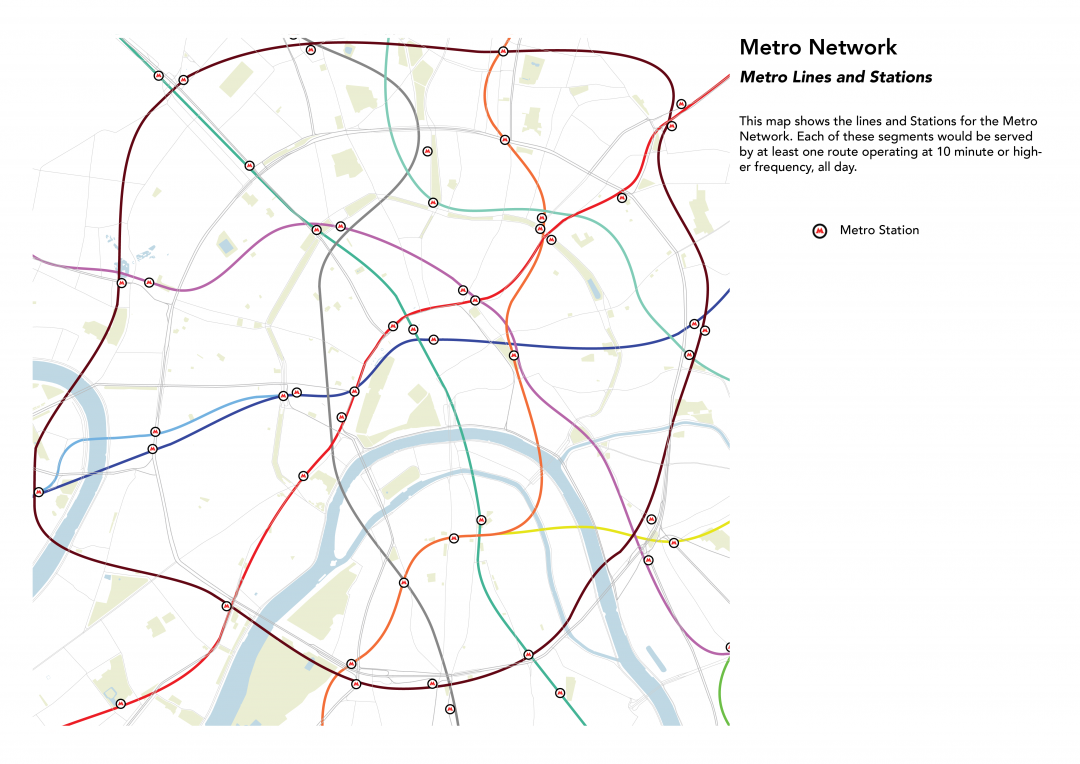

The new network, implemented on Saturday, October 8, looks like this. For greater detail, download the file here.

At this early stage, most lines that could be connected across the core haven’t been connected yet. Note the dark blue line from southwest to northeast, which is the only new one. But the network has been reorganized so that it all flows two-way through the core of Moscow, serving the same places in both directions. This is already a huge improvement. Note the vast increase in the number of wide lines — meaning very high frequency. (They are all colors in this map but only hot colors in the existing system map above.)

As always when you’re trying to expand liberty and opportunity for most people, the result is fewer routes running more frequently in simpler, straighter, two-way patterns.

And That’s Not All …

We got to this network by first designing a network for 2018, then backing up to identify the things we could implement immediately. That means there’s more to come: The next phase combines these routes into more patterns that run right across the city. That means even more frequent and direct routes, even simpler routings, even better access across this dense and diverse urban core, all while reducing the actual volume of buses along the Kremlin Ring and vastly reducing the number of buses that need to park there at the end of the line. We look forward to being able to show those maps soon!

Hopefully this new network can still be served with as many efficient, zero-emissions trolleybuses as the old network was, and hopefully grouping the lines into simpler high-frequency routes can be a guide for future investment in bus lanes, electrification, and conversion to LRT. Also, it looks like the buses and trolleybuses are finally being unified under a single numbering scheme! Maybe trams will get in on this too eventually.

This looks great! We just need to hope that the public accepts the changes.

Tel Aviv went through a rationalization of the bus network a few years ago, but it was ill-explained, and the public pushed back and got several of the good changes reversed. Take a look for example at route 5 (navy blue) in the following maps:

http://humantransit.org/2012/07/guest-post-a-readers-struggle-to-map-tel-avivs-transit-network.html

The top map is the redesigned, (more) rational network. The bottom map is after the pushback, where route 5 reverted to its old pattern that looks like an elongated figure-8, the result of three separate route extensions starting in the 1960s. Going back to the old pattern made little sense, but that’s what happens when politicians don’t back their transit planner because they can’t stand up to the little old lady who lost her personal bus stop. Hopefully the Moscow politicians can do better.

This is one thing that totalitarian governments have the potential to do quite well. If the people in charge have the support of Putin and don’t need the support of the general public, they don’t have to worry about the little old lady.

Of course, it also means that if they decide to level half the city to build more freeways, there’s no stopping that either, so lack of accountability can be bad too.

Interestingly, most of the old routes have been largely unchanged since the Soviet days with their totalitarian city planning. I feel like these changes are in part a result of the influence of the city reformers who manage to exert some democratic influence at the local election level, now that the central government has allowed the Mayor of Moscow to be elected rather than appointed by Putin.

Well the mayor of Moscow is the former head of Putin’s presidential administration. But indeed he was elected this time. I would be careful to see now reformers at work or real democratic influence in that move. On the other hand he acts according to the people’s will in his own view – as Putin reflects automatic the will of the Russian people, if by elections or without. That is how such leaders view themselves and are viewed by a part of the population. Germany, my home country, has some experience with that kind of leaders and when I look at Russia in the last years I understand better how Germany changed in the 1930ies. And by the way, quite a lot of planning decisions in the 1930ies till 1945 were really good – but overall in retrospect Europe would have been better off without that kind of leadership.

Outstanding work, Jarrett!

Awesome work, but I have to note that it’s amazing how for commenters, this highly collaborative project that received a plenty of public input still boils down to Putin and totalitarianism. Come on, people! Please, read some more balanced reporting on Russia!

Happy 2018! Any follow up to the implementation?