In last year’s “microtransit week” series, I challenged the widely promoted notion that “new” flexible transit models, where the route of a vehicle varies according to who requests it, are transforming the nature of transit, and that transit agencies should be focusing a lot of energy on figuring out how to use these exciting tools. In this piece, I address a more practical question: In what cases, and for what purposes, should flexible transit be considered as part of a transit network?

For clickbait purposes I used “microtransit” in the headline, but now that I have your attention I’ll use flexible transit, since it seems to be the most descriptive and least misleading term. Flexible transit means any transit service where the route varies according to who requests it. As such it’s the opposite of fixed transit or fixed routes. But the common terms demand responsive transit, on-demand transit and “microtransit” mean the same thing.

This article is specifically about flexible transit offered as part of a publicly-funded transit network. There may be all kinds of private-sector markets — paid for by institutions or by riders at market-rate fares — which are not my subject here. The question here is what kind of service taxpayers should pay for.

As I reviewed in the series, the mathematical and historical facts are that:

- Flexible transit is an old idea, and has long been in use throughout the world. No living person should be claiming to have invented it. The only new innovation is the software and communications tools for summoning and dispatching service. You can now summon service on relatively short notice, compared to old phone-based and manually dispatched systems that only guaranteed you service if you called the day before.

- Flexible transit is extremely inefficient compared to fixed route transit, for reasons that no communications technology will change. Flexible services meander in order to stop at or near each person’s destination. Meandering consumes more time than running straight, and it’s less likely to be useful to people riding through. Fixed routes are more efficient because customers walk to the route and gather at a few stops, so that the transit vehicle can go in a relatively straight line that more people are likely to find useful.

- How inefficient are flexible services? While there are some rare exceptions in rare situations, few carry more than 4 customers per driver hour. In suburban settings, fixed route buses rarely get less than 10, and frequent fixed route services usually do better than 20.

- There is no particular efficiency in the fact that flexible transit vehicles are smaller than most fixed route buses, because operating cost is mostly labor. You can of course create savings by paying drivers less than transit agencies do, but if a particular flexible service achieves a low cost per rider, that’s not because it’s flexible. It’s because you’re paying the driver less.

- The only places where flexible service is the most efficient way to achieve ridership are places with very, very low transit demand, like small towns, rural areas, and the lowest-density suburbs. If there is no demand for fixed routes that could carry more than 4 boardings per driver hour, you might as well run flexible.

- Therefore, except in very low demand places, flexible transit makes sense only if ridership is not the primary goal of a service. If your goal is coverage, however, they may still have a role.

All transit agencies must balance the competing goals of ridership and coverage. Coverage means “providing access to transit regardless of whether many people use it.” A typical measurement of coverage is “___% of population is within ___ distance of transit service.” Coverage goals arise from popular principles such as “leave nobody behind,” “be there for people who need us,” and “provide a ‘fair share’ of service in every city or electoral district.” They are important goals to many people, but they tend to conflict with ridership goals, because they require running lots of service that has no hope of every being highly productive in ridership terms. (For a fuller explanation of this critical concept, see here.)

To provide clear direction to planning, we always encourage transit agencies to form a clear policy on how much of their resources should be set aside for service whose goal is a high coverage, not high ridership.

Once you have decided to invest some of your resources in coverage service, and know that ridership is not the point, flexible service may have a role. That’s because if your goal is take credit for bringing transit close to many homes, it’s sometimes more efficient to do that without actually near every home every hour.

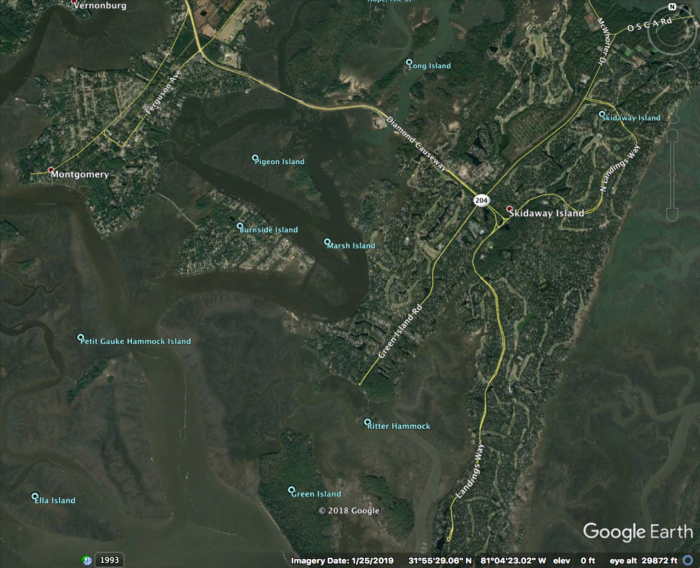

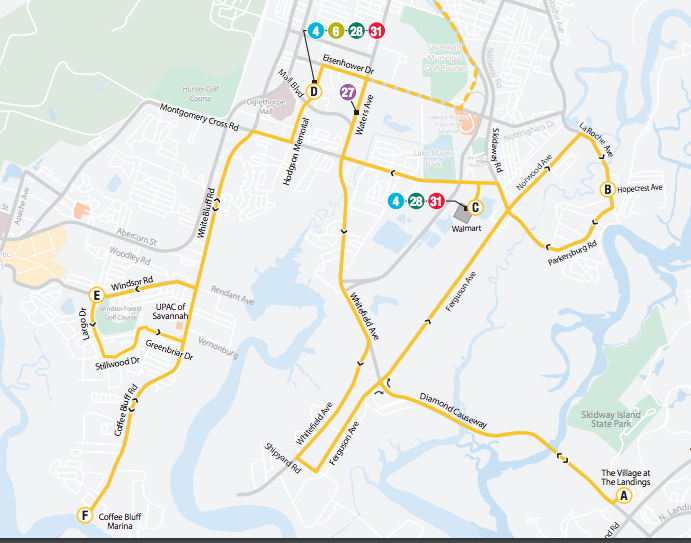

In a great deal of American suburban development, you’ll find things like this:

This series of peninsulas and islands on the south edge of Savannah, Georgia is covered with very low-density residential development, in which entire neighborhoods are effectively cul-de-sacs. A fixed route that tried to cover this area would have to go out each peninsula, turn around, and come back. In fact, there’s a bus route that tries to do that.

It’s a rare example of a route who’s ridership is so low that flexible service might do better, and it’s not hard to see why. Few people would be willing to ride through all these loops.

A flexible service could service this area with fewer driver hours. To do this, it would allow enough time to go to perhaps half of the peninsulas in each hour, but would take credit for covering all of them. That way, it would provide the lifeline transit access that is coverage service’s goal. If enough people lived in landscapes like this, then this tool could help an agency satisfy a target like “90% of residents are within 1/2 mile of service.”

Flexible service isn’t always the right coverage tool. There are many areas where density is too low to attract ridership, but where the street network puts most homes and destinations within a reasonable walk of through-streets. Fixed routes can cover those areas quite efficiently, even when meeting a coverage goal. But flexible services do have a place in the coverage toolbox.

However, contrary to almost all “microtransit” marketing, ridership is the death of flexible service. Suppose that a flexible service on these peninsulas was so attractive that many people began calling it. Then the flexible route van would be expected to go to every peninsula every hour, which is impossible. So more vans would have to be added, still at a very high cost/rider. This process would devour the limited coverage budgets of most agencies, and if those agencies haven’t established a clear limit on what they’ll spend on coverage service, this process can start threatening high-ridership service. At that point, someone should ask: If you end up deleting a bus carrying 30 people/hour so that you can run a van for 3 people/hour, aren’t you basically telling 27 people/hour to buy cars?

So attracting many riders to flexible services is the last thing a transit agency should want to do. In fact, when flexible services become too popular, they have to be turned back into fixed routes. Imagine that a flexible service covering the area above got so popular that you needed three vans to run it. At that point you might as well just run a separate fixed route for each peninsula, at which point each one could be reasonably straight. Still, though, three buses may be more than this particular area deserves, when you look at the total budget for coverage services and spread it over the whole region. So if you really want to claim that you’ve covered all of these peninsulas, you want flexible service, but you also want to take every possible step to keep ridership down.

For this reason, too, flexible transit must avoid being more convenient than fixed routes. It may need to have a higher fare, and it certainly shouldn’t offer service “to your door.” If the goal is coverage to areas where fixed routes don’t work, like these Savannah peninsulas, then you should provide the same quality of service that fixed routes do, which is to say, service to a point within a short walk of your house. This keeps the van out of cul-de-sacs and gravel roads, allows it to follow a somewhat straighter path, and thus allows it cover more area in an hour, which is the whole point.

So most discussion of flexible services or “microtransit” is missing the point. The Eno Foundation report, for example, went to great length to sound optimistic about pilots that were achieving three passengers per service hour – a worse-than-dismal performance by fixed route standards. Flexible service will never be justifiable if the goal is ridership, because if ridership were the goal you wouldn’t serve places like these low-density peninsulas at all. Only if the goal is coverage do these services ever make sense, so only in that context does flexible service appear as a possible solution.

Unfortunately, plenty of “microtransit” marketing is still sowing confusion about this. Transloc promises to “solve the frequency-coverage dilemma,”[1] which is dangerous nonsense. “Microtransit” is a kind of coverage service, not a way to avoid having to think about how much service to devote to coverage goals.

Flexible service will never compete with fixed route on ridership grounds, so it should stop pretending that it can. Market the service as what it is. It’s one tool for providing lifeline access to hard-to-serve areas, where availability, not ridership, is the point.

[1] Transloc page https://transloc.com/microtransit-ondemand-software/ as of August 28, 2019.

How does “flexible transit” compare to the rest of the spectrum between taxis and buses? Is it just a new name for dollar vans, jitneys, share taxis, Marshrutkas, etc. Those seem to be self-sustaining where labor costs are low.

There is a hybrid system fairly common in the Midwest, mainly in small towns and outer suburbs: it’s called route-deviation service, where there is a basic bus route but deviations can be arranged up to a certain distance from the route, often for an extra fee, by calling the dispatch office ahead for pick-up or often by directly asking the driver for drop-off.

Here are links to some examples:

https://www.metrotransit.org/Data/Sites/1/media/pdfs/Schedules/RouteMaps/46/420Map.pdf

https://www.cityofwinona.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/03-20-2017-revised-transit-brochure.pdf

https://www.cityofwinona.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/DAR-Deviation-Brochure.pdf

https://docs.google.com/viewerng/viewer?url=https://powr.s3.amazonaws.com/app_images/resizable/2019%2BSteel_02dcce2a_1545335348638.pdf

In the classic debate about ridership vs. coverage, there is one dimension that is often neglected and that’s what I like to call “directional coverage”. Directional coverage is about people not just having *some* bus that goes by their house, but the ability to travel both north/south and east/west, rather than just one or the other.

In many cities, the demand patterns point overwhelmingly along the radial corridors that go to/from downtown, so the ridership-focused routes will all be radial, rather than crosstown routes. But the budget for “coverage” routes isn’t interested in serving the crosstown market either, since they would fail the test of being the “only service in the given area”. After all, any cross-town trip is still possible by riding one (ridership-oriented) radial route all the way into downtown, and another back out. It might mean an hour+ bus trip for what would be a 10-15 minute drive, but least it’s *possible*.

It is the lack of “directional coverage in traditional bus routes that leaves many people wishing for microtransit, even in populated parts of the city with relatively straight gridlines. Because at least Uber and Lyft will take you on a crosstown trip when you want to make a crosstown trip, rather than forcing a long detour through downtown because most of the ridership comes from downtown-bound passengers.

It is for this reason exactly that I wasn’t on board with the concepts for the Cleveland redesign, for example. They weren’t well thought out and there is * literally * no crosstown service on those maps connecting the populated areas on both sides of the Cuyahoga river/industrial areas. Yes, a couple radials touched endpoints but given all that I have read on this website that seems really, really weak.

I was involved with the development of the Flex service for Outer Cape Cod http://www.capecodtransit.org/flex-route.htm which is a deviated fixed route service. The service has fixed stops but will deviate up to 3/4 mile on request. It has been in operation since 2005 and serves a seasonally sparse population and the more robust summer population well. I feel this is a good example of an innovative “flexible” transit service tailored to the needs and constraints of the communities it serves.

Fantastic clear thinking Jarrett.

For the example given, the big risk with an hourly flexible service is deviation demand to go to more than half the coverage area such that you can’t keep to a timetable with fixed resources. So you lose if ridership is low (dismal productivity) but you also lose if ridership is higher (travel time blows out and/or costs blow out and/or you have to refuse bookings). You could try to get around the timetable reliability problem by not having a fixed timetable but that makes it even harder to use and wait times could blow out instead. Maybe there is a very narrow band of ridership where it works reasonably okay, but that would be easily lost with a little change in ridership. I’m not finding much upside with a flexible transit approach.

So what’s the fixed route alternative then? You could run two fixed routes every two hours, serving half the coverage area each. There would then be no deviation demand risk, you wouldn’t need to worry about ridership growth, you wouldn’t need to divert operational funds into running a booking system (eg you could buy a longer span of hours instead), the service would be much easier to access (no bookings required and services can appear in trip planner results), the service would be reasonably reliable, and operating costs would be fixed. Sure, two-hour headways are not very convenient (you’d have to organise your day around the timetable) but it would still be an available lifeline. Depending on the rules of your jurisdiction you might be able to merge with a school bus service to increase peak frequency up to hourly. All up, it might be a more appropriate service level investment for a very low demand catchment, leaving funds available to run patronage orientated services elsewhere.

“Flexible transit services have a very high operating cost per rider, and always will…”

Always is a long time. 5 years until autonomous taxis, or 12 years until autonomous taxis, or 22 years until autonomous taxis is wayyy sooner than that. If you want to exclude autonomous taxis from the discussion you should say so, but they’ll happen eventually and upend the economics of parts of transit systems.

The implication is, “very high operating cost per rider *compared to the operating cost of fixed routes*…”

If AVs (or some other technological breakthrough, change in labor regulations, or any other change) make it significantly cheaper to operate a vehicle, running that vehicle in a straight line on a fixed schedule will still be a fraction of the cost of running it in a meandering path through neighborhoods at specific times requested by riders. And it always will be.

Exactly. Folks don’t quite get this. Take away the driver, and suddenly there are a lot of routes that are far more affordable. One of the big selling points to a dynamic system is that you have less waiting. Rather than sending a big bus on the big street every half hour, the van will come around when you want it (more or less). Fair enough. But if there is no driver, than vans go on that big street every five minutes. Another big selling point to these on-demand systems is they work like taxi-cabs. They take you where you want to go — no transfers. But if there are vans and buses running every five minutes, then the wait time is actually less than an on-demand system. The transfer penalty is minimal, and the system is more efficient.

You just can’t escape the geometry. Micro-transit makes sense only as a low volume form of coverage service.

In the Santa Clara County case providing flexible transit as a glide path for existing riders is probably necessary in order to collapse the system and avoid stranded riders from lobbying their politicians to keep service. That has worked well in Orange County where the 191 and 193 buses in San Juan Capistrano and San Clemente were cancelled and replaced with Lyft subsidies. The deviations were doing much less than 10 passengers per hour. In a democracy, people paying the bills have a say in what coverage they get, and telling 27% of the public that they don’t even get a bus an hour within a half mile of their home may not engender those people from supporting transit.

Yep, sounds like a classic case of low-volume, coverage service put in place because that is the political preference. Nothing wrong with that. But pretending that this is somehow a new and wonderful invention that solves the ridership-coverage trade-off is simply untrue.

I work for a public transport operator, and we’re working on the flexible transit you mentioned, one that doesn’t go door-to-door but a short walk away. Like you said, it’s a coverage service looking to add declining ridership on the fixed route and let it avoid inefficient detours.

If there’s a small number of users of a transit route, are there precedents for consulting directly with customers on the choice of fixed route schedule? For many customers, the benefit of fixed-route vs. dial-a-ride services is the ability to negotiate the ride schedule in order to meet appointments, etc… Perhaps Silicon Valley innovators could focus on optimizing scheduling instead of routing to achieve the public benefit they seek.

FWIW, I was involved in a kind of flexible transit solution. In my former hometown, the train station is in the middle between the two towns sharing it. There is a bus route providing a local service, but only every hour. The idea we came up with, and which also got implemented is a fixed route, essentially for getting passengers from the train to the towns, which means that there is essentially passengers getting off.

The key was that people telling the driver where they want to get off, and the driver was allowed to move a stop from one place to the other one. For me personally, that was very helpful, because instead of the intersection with the street leaving to my home, there was a shortcut using a stair to a dead-end street, which was way shorter. With the time, the drivers knew where I wanted to get off, when I said, “at the stairs”… and neighbors were asking for that stop too.

Despite the fact that the driver was officially not allowed to change the route, he did it from time to time; I recall an evening with very bad rain, and I had guests from overseas… and the driver almost got us to the front door (and we were not the only passengers by far).

Anyway, this concept may be useful for places where there is no scheduled pick-up.

This reminds me of a school bus route I used to ride. On the way home, I started switching from the route I was officially assigned to to a nearby route that stopped half a mile away from my house, because it took a more direct path and spent less time meandering. After noticing that the bus passed by an intersection a mere 1/4 mile from home, I one day decided to ask the bus driver if they could just stop there and let me off. After a few days of this, the bus driver learned the routine and the unofficial stop effectively functioned like an official stop. That said, I never dared to use that stop for the morning commute, so that approach does have its limitations.

In the world of transit buses, the closest I’ve seen to that are some rural bus routes which follow a fixed route, but allow passengers to get on and off the bus anywhere along the road where the bus driver deems it safe, even if there isn’t a bus stop sign. On rural roads, this is practically the only way to make service usable, as it’s too expensive to put up a separate bus stop sign in front of every house. Yet, on roads without sidewalks, making people walk to the nearest intersection with a bus stop would be unsafe.

I also rode a bus once where the bus followed a fixed route for able-bodied passengers, while allowing disabled customers to call a phone number in advance to request deviations. By having the fixed-route do double-duty, it allowed the agency to avoid the expense of running separate paratransit shuttles, while still providing curb-to-curb service to wheelchair-bound/mobility limited passengers, as mandated by the ADA. This in turn, meant better frequency and span on the fixed route than would otherwise be possible. The tradeoff of course, is that at any moment, your “fixed route” ride might decide to take a 10-minute detour to pick up or drop off a paratransit customer, thereby making your travel times somewhat unpredictable.

I’m always a bit bemused by the argument that transit agencies have to run service everywhere, no matter how minimal/non-existent ridership is. We don’t expect school districts to build schools in areas without children. But somehow transit agencies are “obligated” to serve very low density areas with fragmented road patterns.

“We don’t expect school districts to build schools in areas without children.”

You sure about that? My cousins went to this school.

Start zooming out.

https://goo.gl/maps/BZqVoHi8xvtVtamV9

Merseytravel (the public transport agency covering the Liverpool city region in the UK) is to run a twelve month trial whereby service 211 Speke Circular (a service run under contract to the transport authority) is to be replaced by an ArrivaClick demand responsive service. Looking at the route map of the 211 you can see it comprises two connecting one-way loops making for circuitous and lengthy journeys.

https://www.merseytravel.gov.uk/about-us/guide-to-Merseytravel/Documents/211%20Speke%20circular%20(from%2029%20April%202019).pdf

https://www.busandcoachbuyer.com/arrivaclick-to-replace-bus-service-in-speke/

Hybrid is the way to go for medium-density places, but even deviations should try to maximize designated stops. A flex route always serves popular stops with direct routing every trip, but also deviations. For less popular stops, especially where located off route, it would be efficient to serve these only when requested. Nothing frustrates riders on board more than making a bunch of turns for no one getting on or off. Tech enables turns to change on demand. Flex stops would be similar to fixed stops, just only served on demand. And with new tech, these special stops can be served more immediately upon request, including real-time turn directions and announcements for driver and rider alike. GPS tech enables a rider to locate their nearest fixed and flex stops, plus real-time data for when to get there, and/or request a deviation to a flex stop, if deemed more convenient by the rider. Of course, tech also enables a message to the on-demand rider when their request exceeds the timing or scheduling limits of the next trip, too. But then, the rider will be given the choice of walking to the next closest fixed stop or waiting for the next available deviation to the flex stop.

Perhaps it’s like Hyperloops, Maglev, and Monorails – designed to protect the one-person-per-private-vehicle hegemony for a 2nd century by preventing investment in proven systems.

Jarrett, Microtransit is a variant of Demand Responsive Transit in that the Microtransit service area is geo-fenced and small – just a few square miles depending on population and employment density. The problem with microtransit is over-promising – We’ll take you anywhere within that geofenced service area. If the neighborhood wants to subsidize that high level of service, bully for them. To make this financially sustainable in a rural area or suburban sprawl, the guidelines need to be stricter.

I see Microtransit as sustainable in a rural or suburban area if the structure is Many-to Two: a transit hub for commuters and to whichever grocery/pharmacy will kick in a subsidy for those who due to age, disability or whatever are not commuters. Like the post office, not every neighborhood gets service on demand or on-the-hour. This is where microtransit needs to emulate fixed route. We’ll be in your neighborhood at X and maybe also XX minutes after the hour, call us if you want to be picked up. At Y minutes after the hour, the small bus will be in a different neighborhood. This is how transit can maintain coverage while still concentrating resources on productive routes.

Microtransit labor costs can be tamped down by subcontracting and using non-CDL size vehicles.

Looks like the economy and geometric realities of on-demand micro transit are beginning to be realised in Oxford, England where a commercial operation called “Pick Me Up’ is struggling to pay its way. Now the bus company (one of the large UK bus groups) is latching onto a recent announcement from the new UK government that buses matter, and promising money (which in no way makes up for the austerity cuts in recent years). Government plans include funding for new demand responsive bus services.

Some of the comments below the article are interesting, talking about not being able to rely on getting to your destination at your desired time, and about the lack of people per trip.

https://www.oxfordmail.co.uk/news/18194404.pickmeup-bus-service-scrapped-without-funding/?ref=ar