Is your transit agency succeeding? It depends on what it’s trying to do, and most transit agencies haven’t been given clear direction about what they should be trying to do. Different people have different goals for transit, and those goals lead to different kinds of network.

To see why, look at this little fictional town. The little dots indicate dwellings, jobs, and other destinations. The lines indicate roads. Most of the housing and destinations in the town area concentrated around two main roads.

Imagine you are the transit planner for this fictional town. The dots scattered around the map are people and jobs. The 18 buses are the resources the town has to run transit. Before you can plan transit routes you must first decide: What is the purpose of your transit system?

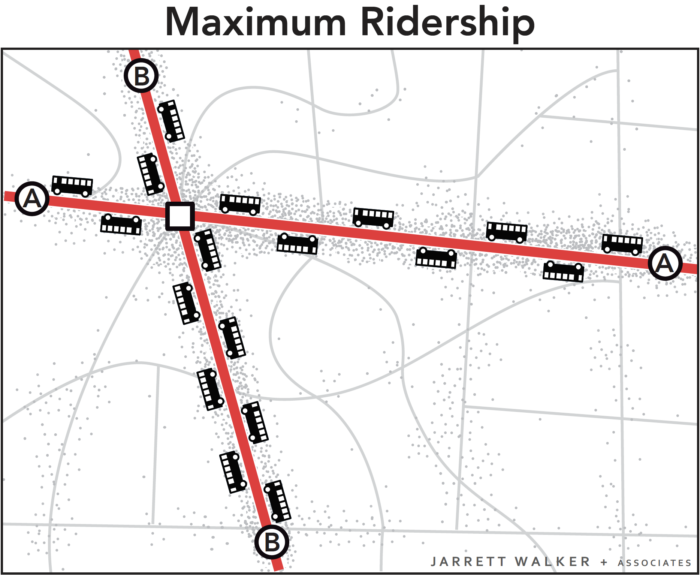

Designing for Ridership

A transit agency pursuing only a ridership goal would focus service on the streets where there are large numbers of people, where walking to transit stops is easy, and where the straight routes feel direct and fast to customers. Because service is concentrated into fewer routes, frequency is high and a bus is always coming soon.

This would result in a network like the one below.

All 18 buses are focused on the busiest areas. Waits for service are short but walks to service are longer for people in less populated areas. Frequency and ridership are high, but some places have no service.

Why is this the way to maximize ridership? Frequency tends to have huge payoffs. Most people find a bus coming every 15 minutes to be more than twice as useful as a bus coming every 30 minutes. Frequency also makes it easier to change between buses, which expands the range of destinations people can reach. So when we concentrate frequency where the most people will benefit from it, we tend to get the best ridership results. If you want to read more about this, see here.

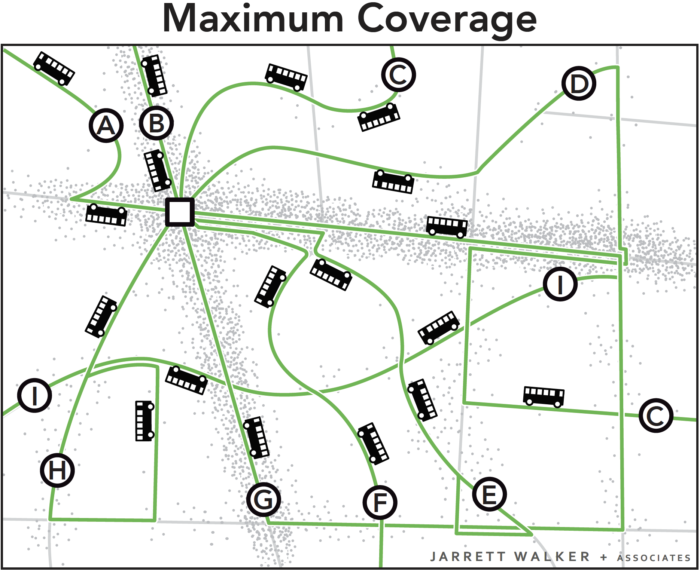

Designing for Coverage

A network designed only for ridership would not go to many parts of the city at all. If you think a transit agency owes some service to everyone in the community, you want a network designed for coverage. To achieve this goal, the transit agency would spread out services so that there would be a bus stop near everyone. Spreading it out sounds great, but it also means spreading it thin. The resources would be divided among so many routes that it wouldn’t be possible to offer much service on any of them. As a result, all routes would be infrequent, even those on the main roads. Infrequent service probably isn’t coming when you need it, so it isn’t very useful, so not many people would ride.

The 18 buses are spread around so that there is a route on every street. Everyone lives near a stop, but every route is infrequent, so waits for service are long. Only a few people can bear to wait so long, so ridership is low.

(By the way, in the coverage network I could have used on-demand or “microtransit” vans instead of buses on fixed lines. This is another tool for providing low-ridership coverage service.)

In these two scenarios, the town is using the same number of buses. These two networks cost the same amount to operate, but they deliver very different outcomes.

Both Goals are Important

Ridership-oriented networks serve several popular goals for transit, including:

- Reducing environmental impact through lower Vehicle Miles Travelled.

- Achieving low public subsidy per rider, through serving the more riders with the same resources, and through fares collected from more passengers.

- Allowing continued urban development, even at higher densities, without being constrained by traffic congestion.

- Reducing the cost of for cities to build and maintain road and bridges by replacing automobile trips with transit trips, and by enabling car-free living for some people living near dense, walkable transit corridors

Coverage-oriented networks serve a different set of goals, including:

- Ensuring that everyone has access to some transit service, no matter where they live.

- Providing lifeline access to critical services for those who cannot drive.

- Providing access for people with severe needs.

- Providing a sense of political equity, by providing service to every municipality or electoral district.

Ridership and coverage goals are both important to many people, but they lead us in opposite directions. Within a fixed budget, if a transit agency wants to do more of one, it must do less of the other.

Because of that, cities and transit agencies that lack adequate resources need to make a clear choice regarding the Ridership-Coverage tradeoff. In fact, we encourage cities to develop consensus on a Service Allocation Policy, which takes the form of a percentage split of resources between the different goals. For example, an agency might decide to allocate 60 percent of its service towards the Ridership Goal and 40 percent towards the Coverage Goal. Our firm has helped many transit agencies think through this question. Here is an explanation of how this conversation played out in a typical US transit agency.

What about your city? How do you think your city should balance the goals of ridership and coverage? There is no technical answer. Your answer will depend on your values.

Further Reading

Jarrett Walker’s Journal of Transport Geography Paper, which first introduced this concept, is here.

Thinking outside the box: in your hypothetical city, allow denser zoning outside your 2 main streets to concentrate uses and allow more people to walk and bike.

That’s definitely the long term solution, and if your transit agency / government is smart, they’ll be aiming for that. But most transit organisations are asked to provide services now.

Most transit providers have no power to (re)zone anything, nor do they have much influence over how street networks are laid out. This is true in many English-speaking countries, but especially in the US. It’s nice to think outside the box, but as Murray says, transit providers still have to operate services within urban landscapes as they already are today, not as they ideally should be.

This trade-off doesn’t really address locations where the funding is not adequate to meet either goal.

Say you have a grid-based city, 25 avenues by 25 avenues, with perfectly distributed population. You have 4 bus routes, 2 running north-south, two running east-west, at 30-minute intervals.

Reducing frequency to every 60 minutes to add another route or two isn’t going to build ridership. Eliminating a couple of routes to improve frequency isn’t really going to help either.

The only solution is to up the budget.

I think going to these municipalities and selling them on the idea that they can build ridership by moving around resources gives them an easy escape hatch from the real issue: they need to make trade-offs with their city budget.

The R-C trade-off is about priorities within the reality of a fixed budget. Even if you have more money you’ll still have a fixed budget.

I think JJJJ has a good point, though, that if the budget is too small, then this trade off may help people understand the theory, but it’s not very relevant to the system. My background is smaller transit systems, and we often just have one bus on the main road, with none on the other roads (in this diagram). There aren’t even resources to move around and make a choice. Sometimes those with the purse strings hear this line of reasoning, look and see that we put all our resources on the main streets, and assume we are ridership goal oriented, when in reality it’s still a coverage service.

None of this is to knock the ridership/coverage trade off, which I think is a very real and helpful way to talk about transit choices. It’s just at some point we’re debating whether a skiff or a dingy is better to cross the Atlantic, when really we need a ship.

Agree. You could say there’s two types of coverage:

– Coverage within a local area

– Coverage among broader districts

For example, let’s say you have two bus routes. Both only run once an hour and both take 75 minutes from start to finish.

The first is a bus route that winds around the suburban streets of a local area, like most “traditional” coverage routes. This means the local area is well covered, but at the expense of other areas.

On the other hand, you have the other situation where you have a bus route connecting districts far apart, but only along the main road.

Both of these examples are “coverage” so to speak but they aren’t the same sort of coverage as each other.

The point is not to increase ridership per se, it’s so that the government and public can know how much is being spent on coverage service and why, and what they’re missing out on by doing it this way. Some networks are in greater need of consolidation, and sometimes the public is willing to and former coverage riders find the consolidated corridors good enough. In other networks they’re far from this point. This issue is not directly related to the issue of whether the city should raise its transit budget: it’s focused on the optimal arrangement of eggs, not how many more eggs are needed. Both of these issues need to be pursued.

I find this example helpful because it reinforces that it’s not just about the budget, it’s also about the size of the fleet. If this town only has 18 buses, and they’re all in use (ignoring spare ratio), you can’t improve service frequency on a key ridership corridor without negatively impacting a coverage route, and you can’t extend service to a currently unserved area without taking service away somewhere else.

And at the same time, it is very much about the budget, and the number of buses is a good analogy that I find more tangible and thus more accessible.

I like the new graphic. It illustrates frequency and resources as well as density and geography. I would be interested in seeing the version for say a 70/30 split. And using some kind of different dashed lines that also indicate frequency. Wait strike that. One thing at a time.

Besides ridership and coverage, there is a 3rd dimension to think about, and that’s speed.

To give an example of this, let’s consider route “I” in the maximum coverage network. Most route route I’s ridership is probably going to come from people traveling between where it intersects the main north/south road and the main east/west road. For those people, route “I” is going to be a straight shot between the two corridors, almost as fast as driving, because the bus will hardly make any stops, due to limited activity centers along the way.

Now, consider the alternative under the “maximum ridership” network, if route “I” doesn’t exist. You get to ride all the way into the center of town on one excruciatingly slow bus that constantly stops to load and unload passengers, then ride back out again another another equally slow bus. (Basically, the more time a bus spends loading and unloading passengers vs. actually moving, the more productive route is, from the agency perspective).

Basically, a 10-15 minute drive down the back road now because something like 5 minutes (wait) + 20 minutes (ride first bus) + 5 minutes (wait) + 20 minutes (ride second bus) = 50 minutes (grand total). Even with everything running frequently, transit has utterly failed for trips in the high-ridership area, due to the lack of the “coverage” route – not because of the actual “coverage” per-say, but because of it’s speed.

While your concern is valid, it’s not a problem in practice for several reasons.

First off, there are several articles on this site about stop spacing and other issues of transit speed. Most notably, this article: http://humantransit.org/2013/03/abundant-access-a-map-of-the-key-transit-choices.html

Thus in the maximum ridership example, you can safely assume that both lines are going to be something of a BRT, with their own lane (and signal priority, etc.) and 4-500 m stop spacing (as is entirely usual in Europe). As such, protected from congestion, it could easily have an average speed close of 30 km/h (20 mph) or so, doing no worse than cars (indeed, beating them during rush hour). (Note: *average* speed. Due to traffic lights and various other causes, cars with a top speed of 50 km/h get somewhere around 30 km/h average for the whole route. Distance traveled over elapsed time.)

In fact, there is a multitude of “fancy” solutions beyond BRT. If crosstown trips are still too slow — perhaps because transit must compete with an urban free-flow motorway — and sufficient budget is available, a single route can be split into an express/local overlaid pair. The express would have stops perhaps 1 km apart, while the frequent local would gather and scatter passengers from its colinear stops to the stops of the express. (There are minor problems with this arrangement, such as the fact that the express has far higher ridership than the local, and consequently — if using buses — a much higher frequency, which is wasted to some degree.) However, it is quite common for the express to be implemented with some form of rail vehicle, e.g. a metro. In this case, a frequent grade-separated (i.e. completely protected from congestion) vehicle with 1 mile (or longer) stop spacing afforded by the colinear collector-distributor bus can easily beat the car for the majority of trips. Look at London or Moscow for great examples of bus+metro systems.

Obviously, the above only apply if the city is large enough to warrant such a “fancy” solution. Most don’t, and simply a 4-500 m (quarter mile) stop spacing frequent bus with a car-free lane does the job just fine.

On the other hand, in the maximum coverage example, it is a virtual certainty that transit would have no protection from car-caused congestion, and that stop spacing would be extremely close — though it wouldn’t matter much, if lots of them are skipped. Consequently, the average speed of transit would be perhaps 15-20 km/h (10-12 mph), and during times where the bus gets stuck in congestion, 5 km/h (3 mph) or walking speed.

Putting the two together, the more frequent service is also faster. This is not a surprise — a service used by lots of passengers makes it politically feasible to speed it up, by taking one lane away from cars and eliminating superfluous stops. As a side effect, buses cycle the route faster, thus each unit of budget becomes even more useful!

On the other hand, a service that is infrequent, and is run due to political compromises in the first place (pretend to provide service for constituents, even though they won’t use it much, because it’s next to useless due to its low frequency) won’t get that sort of streamlining, not least because its speed doesn’t actually matter to the politician making the decision. Taking a lane away from cars for a bus that only runs every 20-30 minutes is not popular, and making stops sparser is entirely counterproductive. When the constituents ask for a stop that they are never going to use to be close to them, a smart politician tells the transit agency to put down lots of stops.

asdf2: I’m not sure about your assumptions. A straight crosstown coverage route doesn’t sound like a typical coverage route, or even a coverage route at all. The coverage routes are in your second example: long milk runs to downtown, sometimes five blocks parallel to a similar route or to a frequent route. Those are the bad coverage routes. The good coverage routes go to the nearest transit/shopping center from an area that’s considered too far from other routes and too essential to leave out of the network. These routes often turn and run on non-arterials because that’s the only way to reach their target endpoint and serve people in between. Some coverage routes may have two anchors (a good transfer/destination point at both ends), but that’s more due to a lucky happenstance that both anchors are available, or it’s an interlining of two theoretical routes (e.g., an L-shaped route) for efficiency or usefulness.

So, there are a lot of cities out there where the fastest road between two major activity centers is “fastest” because there’s not a lot of stuff along the way – so less stoplights and traffic to deal with. When you drive between the two points, this is the road you take.

But buses, as a rule tend to avoid such roads for reasons illustrated in this post – the more activity centers the bus passes by, the more trip pairs it serves, hence the more riders it can serve. This is all great from an agency productivity standpoint, but from a passenger experience standpoint, it means you’re taking a road with more stoplights and congestion to begin with, plus slightly longer distance, all so that the bus can stop at more bus stops (rather than blowing past them because nobody needs to get on or off), rendering the trip even slower.

Of course, in the ideal world, the “bus” along the two major roads would be an underground subway, completely immune to stoplights and traffic jams, and built to load and unload massive quantities of riders very quickly. When building a subway, you *have* to do “maximum ridership network”, or it’s too much money in construction cost chasing too few riders.

Even with buses, it is theoretically possible to achieve similar effects by setting up dedicated bus lanes and transit signal pre-emption. But, in practice (at least in the U.S.), all the roads are going to be designed first and foremost for cars, and the only choice the transit agency has is to throw buses on those roads to sit in the same traffic and wait at the same red lights as the cars do, on top of all the passenger loading at the bus stops.

Again, in such a practical network, the only way to get decent speeds is establish at least a few key crosstown routes, even if the intermediate ridership is weak, so it’s purpose becomes quasi-coverage, quasi-express-between-high-ridership areas.

As an example of what I’m talking about in a real city, consider the following trip:

https://www.google.com/maps/dir/47.6269653,-122.2909053/47.6495782,-122.3046382/@47.6372609,-122.3082431,14z/data=!4m3!4m2!3e3!5i2.

For this trip, the “direct” car road is Lake Washington Blvd. This is the equivalent of route “I” in the fictitious city. By car, the drive is a straight shot, and takes about 10 minutes.

But, the transit network, on the other hand, has no buses that use Lake Washington Blvd. because that road mostly bisects a park, so very few actual homes and businesses to serve between the start and end points of the sample trip in the above link. So, you have to take one bus southwest, then transfer to another bus going north (or stay on the first bus a bit longer and ride the light rail, instead). So, in order to ride transit, you basically have to detour out of the way in order to follow streets where the bus can pick up more passengers along the way, so that the bus spends more time loading/unloading passengers, further slowing things down. The end result is that the 10-minute drive takes about 30 minutes by transit.

In many cases, (and this is one of them) the root cause of the problem may not be so much the transit network, but the fact that the “shortcut” road exists for cars in the first place. For example, if the “shortcut” road were, instead, a bike trail, closed to cars (which would dramatically improve the atmosphere and connectivity of the park), suddenly that 30-minute bus ride looks a lot more appealing, simply because the competing car option becomes less appealing.

In a sense, by creating these “bypass” roads, the road department is creating an unfunded mandate on the transit department, to run buses on them, in order to keep transit travel times from getting out of control compared to drive times.

>>> In a sense, by creating these “bypass” roads, the road department is creating an unfunded mandate on the transit department, to run buses on them, in order to keep transit travel times from getting out of control compared to drive times. <<<

This is something I watched unfold in Portland of the 1960's. Fast and productive routes on 1940's arterials and some very direct older streets were paralleled by the new, not yet congested Interstates. In the case of I-5 north of downtown Portland that included demolishing miles of houses and creating barriers to walking to alternate bus rroutes. And then the remaining people complained that the buses were slow. Service cuts were the response. In cases where the private companies decided to use the new Interstates, former frequent service was divided up into less frequent express and local services.

There is a problem with the thinking that X percent of money should go to ridership and Y percent to coverage. It implies that all routes must be for the purpose of either ridership of coverage. In a real city, many routes are something in between.

And for the maps: The second map seems to implie that all routes in a coverage-based network must have equal frequency. But it would be much better to have higher frequency at the main streets and lower frequency for other routes.

The maps are ficticious extremes to illustrate the point. The “percent for coverage” guideline is to ensure that cities don’t allocate too much or too little for coverage, and that they have strategic coverage goals rather than just defaulting to “Mrs Judith wanted a route here in 1975”. I’m not a transit planner but in my city it’s pretty easy to identify coverage routes: they’re the ones that fall below some ridership threshold and are not “growth-target” corridors (where the agency is trying to jump-start ridership or knows that density will come soon). Some routes have what I consider to be “coverage tails” or “coverage halves”. That may be more what you’re talking about. But agencies do that to save the segment from downgrading or deletion, hoping that it will either increase ridership or the productive part will make the coverage part cost-effective. I don’t know that agencies assign coverage hours to portions of routes, but logically they could and maybe some do, and maybe pretending that the segment its “not coverage” costs less than serving it with a separate coverage route.

Colorado’s Regional Transportation District used route segment productivity standards from the mid-80’s on. We also had “livehead” standards for productivity on trips that might otherwise run as deadheads.

Example: In 1975 I had to catch an early morning flight from Portland to Bozeman. The Tri-Met schedule had the first bus of the morning deadheading out to the airport. Luckily the deadhead went past the end of my block, and luckily the operator was able to see me flagging him in the fog. A livehead standard would determine if the added time to run the trip in service — to a major employment center — was warranted. In the Colorado experience some liveheads were successful – notably on US36 between Denver and Boulder – and some were deleted when they failed.

The problem I’m finding is that there is such intense inequality in American cities that people who in principle would probably otherwise be for transit alternatives to driving (i.e. fast, ridership-aimed transit) end up taking the position that essentially all new transit dollars should be allocated to coverage. This is because the local needy are so fully dependent on transit and unable to drive OR walk that it’s unthinkable to spend money that instead benefits middle class commuters, most of whom can afford a car anyway. Of course this leaves city inhabitants making a lower-than-average income who still need to get to work on time out in the cold. In general, this is a problem with the American left: support for the poor is so nonexistent that every government service from transit to public schools ends up bearing all the responsibility for solving poverty. How you respond to this as a transit activist?