Our work on Greater Cleveland’s transit network is now available online, and we’re looking for people from the area to provide their input through this online survey. The transit agency, GCRTA, hired us this year to help develop transit network alternatives that would illustrate what the transit network could look like if it shifted its focus more towards attracting higher ridership, and what it what the network would look like if it shifted towards extending coverage, as well as what the possibilities may be with different levels of funding.

The local newspaper, the Plain Dealer, has a great article about the networks and what they are intended to illustrate.

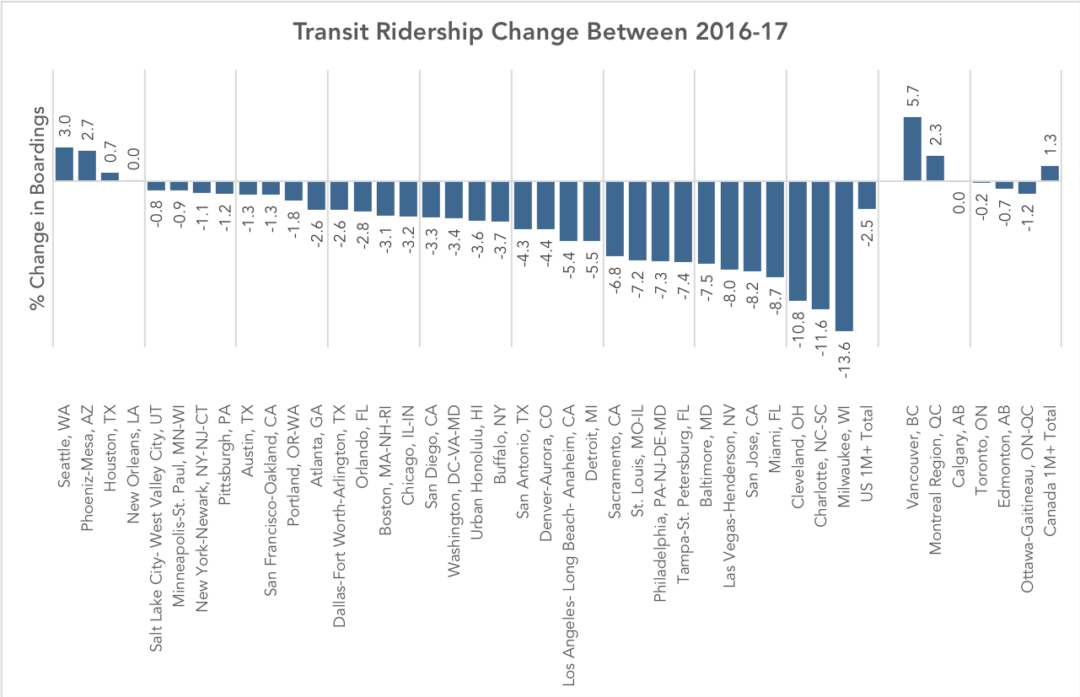

Cleveland is fortunate to have a relatively dense, and walkable pre-war era development pattern across much of the city, but as with most places in the United States, the trend over the past half-century has been the continual spread of residents and jobs to far-flung locations across the region. Since the region as a whole is growing very slowly, or not at all, this slow dispersal of the tax base poses a long-term challenge for the stability of transit resources and travel markets as more people and jobs flee to the margins of Cuyahoga County, or beyond.

When operating resources are limited, as in GCRTA’s case, the ridership/coverage tradeoff is put front and center in any discussion of what transit can do. Today’s network extends to most, but not all, of the developed area of the county, and provides little high-frequency service within the dense, walkable core of the region. Reaching more of Cuyahoga County would mean curtailing frequency in dense areas even more. But building a robust frequent network would require pulling back from many of these lower-density suburban areas, as there is little waste or duplication to reallocate in the current service design of RTA’s network.

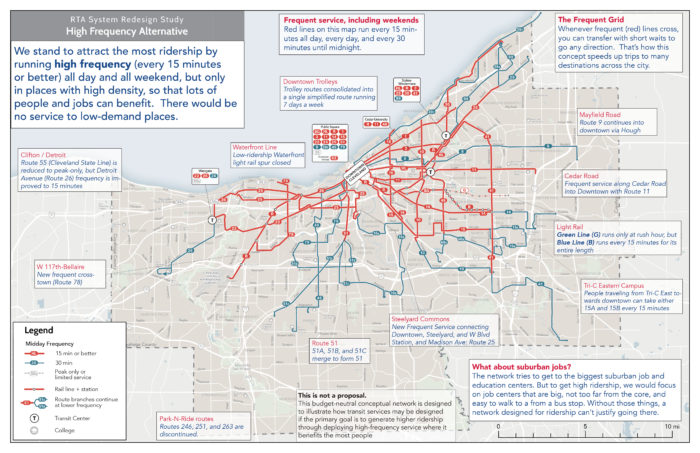

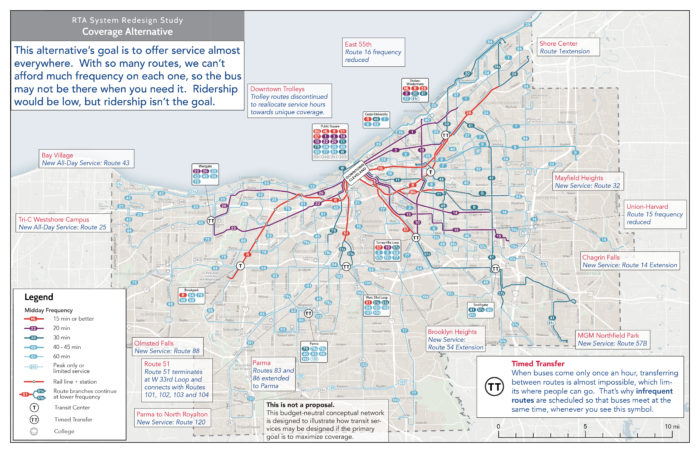

In this context, RTA has brought us in to help explore what the transit network could look like today, if different policy priorities were emphasized more strongly in network design. Further on in the project, we’ll also be developing alternatives for different financial scenarios. Right now, RTA is conducting outreach on two alternatives: a High Frequency Alternative which brings frequent service to most of the dense, walkable central areas of Cleveland and the inner-ring suburbs, and a Coverage Alternative, which spreads low-frequency service to more of county.

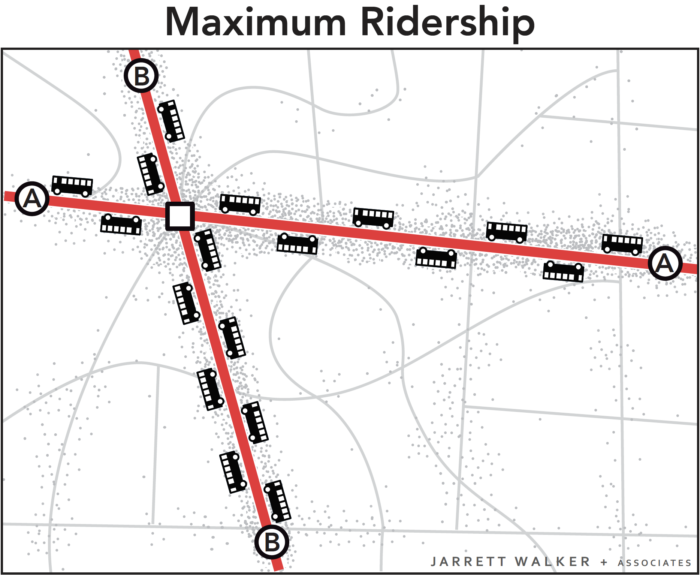

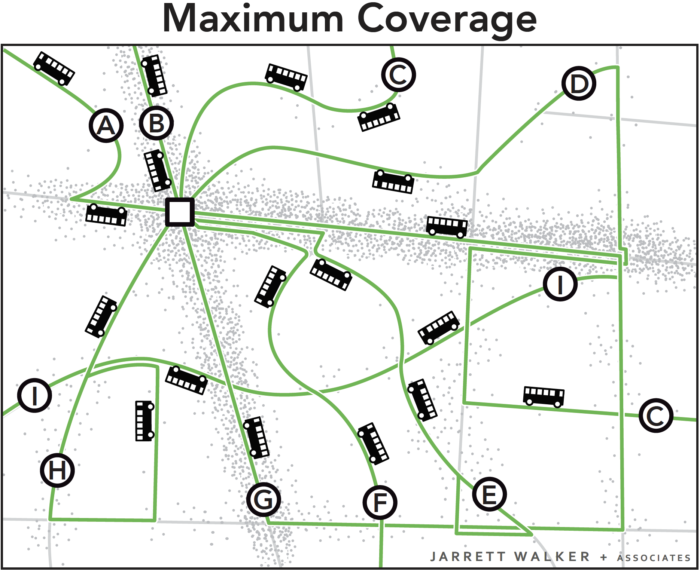

The purpose of these alternatives is to illustrate for the public, stakeholders, and the agency’s Board of Trustees the potential outcomes of a policy choice to focus more on ridership or on coverage. (You can click each map below to explore a larger annotated version).

The High Frequency Alternative concentrates service so that lines run more frequently, reducing waiting times and making travel by transit more convenient. The network would reach fewer places, but where it does reach, trips would be faster than with the Existing Network.

As a result, over 40% more jobs would be accessible by the average county resident in an hour with the High Frequency Alternative. But on the other hand, the reduction in overall network extent reduces the number of people within a ½-mile walk to transit by over 20% from current levels.

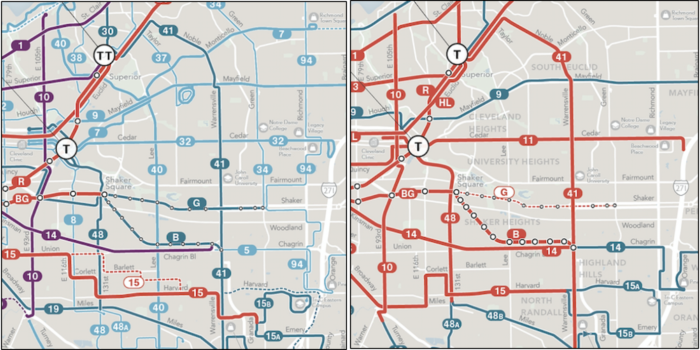

You can compare the structure of the network on Cleveland’s east side to see this principle in action:

GCRTA Existing Network (left) compared with the High Frequency Alternative (right)

On the other hand, the Coverage Alternative spreads out service across the county, but spreading it out means spreading it thin. Frequencies would be lower throughout the network. This means that the network reaches more places but some trips would take much longer. Because these are budget-neutral alternatives, expanding the reach of the network requires reducing service levels on other routes, some routes that run every 45 minutes today would run every 60 minutes, and RTA’s single existing 15-minute bus service would run every 20 minutes. About 25,000 more people would be within a ½-mile walk of a transit stop, about a 5% increase from the Existing Network.

We hope these alternatives clearly illustrate the ridership/coverage tradeoff as it applies to Cuyahoga County and Cleveland. If you live in the area, please tell us what you think! You can learn more about the project and alternatives here. Then, if you live, work or study in Cuyahoga County, be sure take this short online survey.