Like most people who plan public transit, I hate cutting service. Most cities that I work in have obvious markets where more transit would attract more ridership and expand the possibilities of people’s lives. So of course I hate taking service away.

But sometimes we have to. Ever since the Covid-19 pandemic, there have been two large reasons that transit service can’t be sustained:

- Lack of funding. Large agencies that relied on fare revenue, especially those that moved large volumes of people into city centers before Covid-19, are having trouble balancing their budgets. Some face “fiscal cliffs” that will require new funding to stave off service cuts.

- Lack of staff. Across the world, authorities and operating companies are struggling to hire and retain bus drivers. The problem has stabilized in many places but doesn’t seem to be going away.

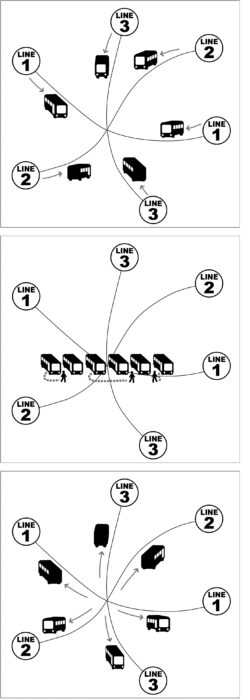

There are two kinds of service cuts, random and planned. When you hear discussion of service cuts, it’s usually about planned cuts. But the alternative to planned cuts is random cuts, so it’s important to know what those are.

Random cuts happen in the course of operations, when not enough drivers show up for work. There are always a certain number of drivers calling in sick, and agencies manage this by paying some spare drivers to be on hand at the operating base, to fill in whatever runs would otherwise be missed. But during the Covid-19 pandemic, these processes were overwhelmed by the number of employees not coming to work. Even today, many US agencies are failing to deliver some of their scheduled service due to lack of staff.

These cuts are random and unpredictable. In many cases, a particular bus never pulls out of the operating base in the morning because the driver of that bus didn’t show up, and there weren’t enough spare drivers on hand. So every trip that bus was going to do will just not be served. In other cases, operations managers are more proactive at reassigning drivers so that the most urgently needed service is saved. In either case, the customer experience is that sometimes their bus doesn’t show up, and there is no way to plan ahead for that because it might happen today but not tomorrow. It all depends on who showed up for work that morning and what decisions were made on the fly at the operating base.

This is a very bad situation, and it’s sadly routine. Why is it still happening at some agencies so long after the pandemic? Because many decision-makers are deciding that random cuts are better than planned cuts. Let’s look at why this happens, and why it’s almost always the wrong choice.

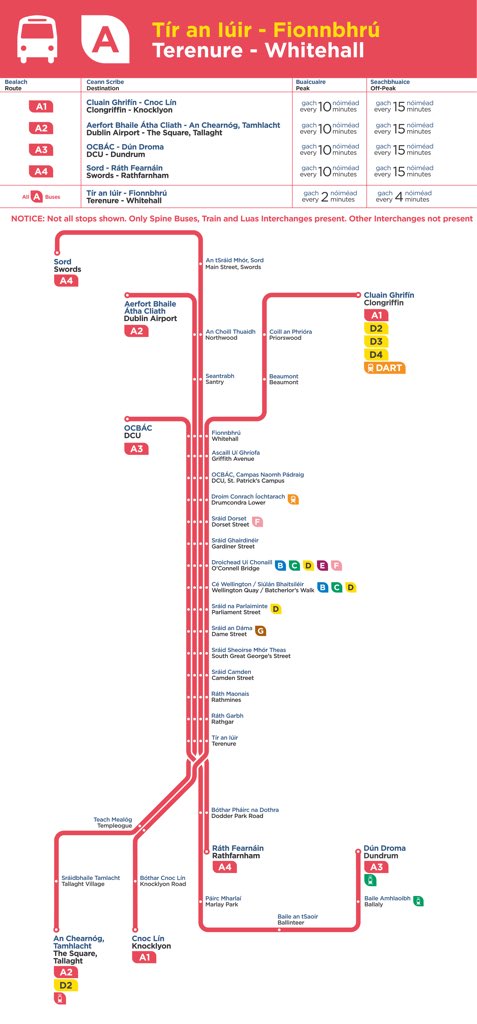

During the pandemic, I happened to be working closely with San Francisco Muni, and one thing that really impressed me is that all through the crisis, they made every effort to plan their scheduled service to match their shrunken workforce. It was chaos in the first months of the pandemic, as it was everywhere, but as soon as they could, they intentionally designed a stripped down network that they could operate reliably with the reduced workforce they still had. Ever since then, as the workforce as grown, they have been gradually and strategically bringing service back. They currently report that over 99% of their scheduled service is operating, far above what many agencies are achieving. Why? Because they designed the scheduled service to be operable in their actual situation.

But to do this, they’ve had to endure a lot of outrage. Riders unite against planned service cuts, because they’re visible and intentional. There’s a staff person putting them forward who makes an easy villain. Sometimes that staff person will even be framed as advocating the cuts, which is ridiculous. Professional transit planners are almost all transit advocates. They want to expand service. If they’re proposing to cut it, it’s because the alternative is worse.

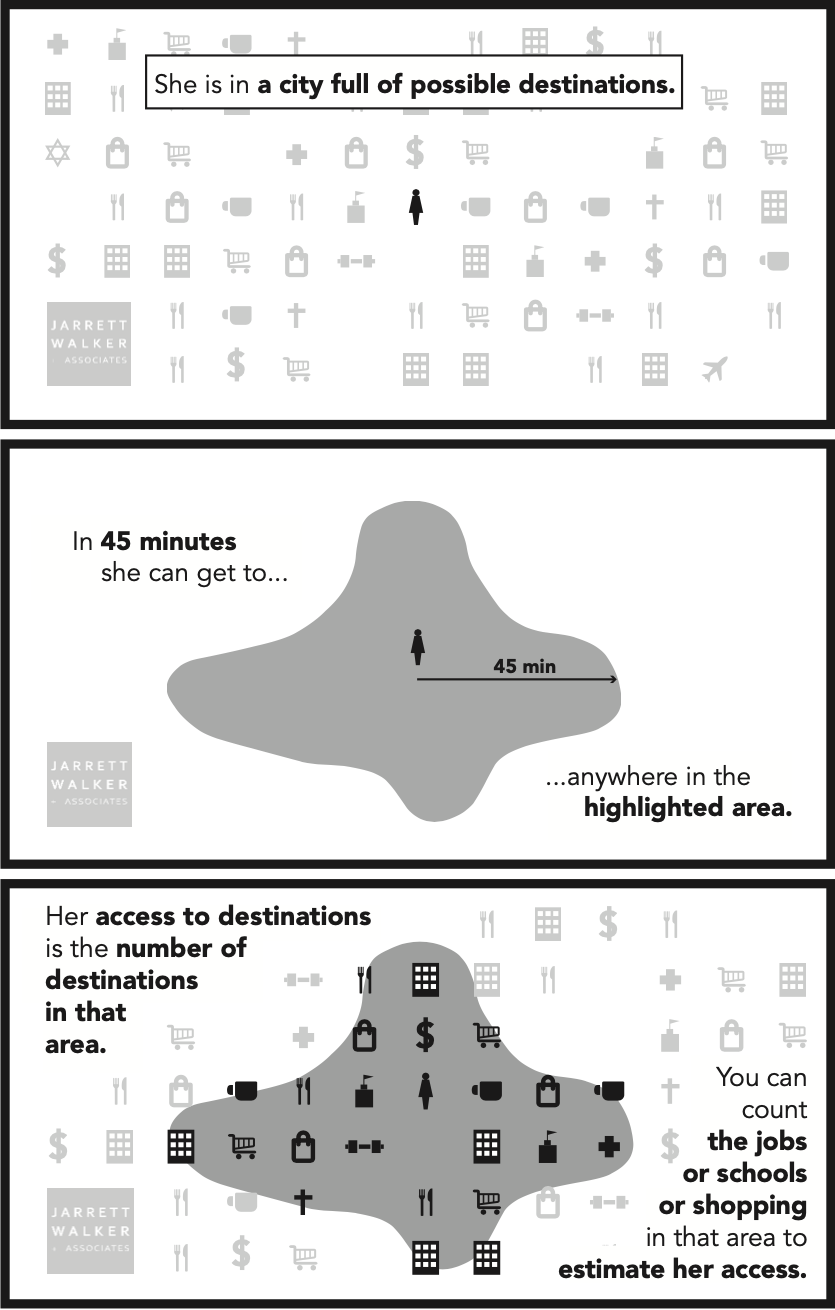

If an agency lacks the staff to run its schedule reliably, then a refusal to cut service in a planned way will just cause more service to be cut randomly. Planned cuts mean that you know that the bus you use will know longer be there, but you can be confident that that one two blocks away, or the one five minutes later, will be there. You will grumble, but it’s likely you can adapt to that. Random cuts, on the other hand, undermine the transit experience for everyone, and do so in a way that nobody can plan for. Sharing the pain among everyone may seem fair, but it’s also a good way to drive away a much larger share of the ridership.

So every time you hear a transit authority debating service cuts, ask what the alternative to the planned cuts is. Is there really a pot of money that can keep the service running? Or is there a workforce limitation, as there is in many cities, that will make an uncut service inoperable? If it’s the latter, then you can make a big show of opposing the scheduled service cuts. But all you’ll have done is condemn riders to random cuts, day after day, which will do far more to undermine confidence in the service.