To complete your trip in a world-class transit system, you may have to make a connection, or “transfer” as Americans say. That is, you may have to get off one transit vehicle and onto another. You probably don’t like doing this, but if you demand no-transfer service, as many people do, you may be demanding a mediocre network for your city.

There are several reasons for this, but let’s start with the most selfish one: your travel time.

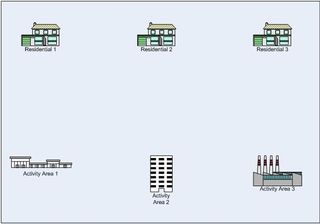

Imagine a simple city that has three primary residential areas, along the top in this diagram, and three primary activities of employment or activity, along the bottom.

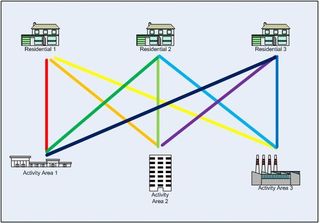

In designing a network for this city, the first impulse is to try to run direct service from each residential area to each activity center. If we have three of each, this yields a network of nine transit lines:

Suppose that we can afford to run each line every 30 minutes. Call this the Direct Service Option.

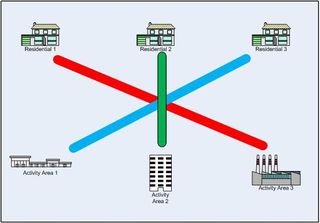

Now consider another way of serving this simple city for the same cost. Instead of running a direct line between every residential area and every activity center, we run a direct line from each residential area to one activity center, but we make sure that all the resulting lines connect with each other at a strategic point.

Now we have three lines instead of nine, so we can run each line three times as often at the same total cost as the Direct Service option. So instead of service every 30 minutes, we have service every 10 minutes. Let’s call this the Connective Option.

Asking people to “transfer” is politically unpopular, so the Direct Service option is the politically safe solution, but if we want to maximize mobility with our fixed budget, we should prefer the Connective option. Consider how long at typical trip takes in each scenario, from the standpoint of a person whose needs to leave or arrive at a particular time.

Let’s arbitrarily look at trips from Residential Area 1 to Activity Area 2. For simplicity, let’s also assume that all the lines, in all the scenarios, are 20 minutes long.

In the Direct Service scenario, a service runs directly from Residential Area 1 to Activity Area 2. It runs every 30 minutes, so on average, the waiting time is 15 minutes. Once we’re on board, the travel time is 20 minutes. So the average trip time is:

Wait 15 minutes

+ Ride 20 minutes

= 35 Minutes.

Now look at the Connective Option. We leave Residential Area 1 on its only line, which runs every 10 minutes, so our average wait is 5 minutes. We ride to the connection point and get off. Since this point is halfway between the residential areas and the activity centers, the travel time to it is 10 minutes. Now we get off and wait for the service to Activity Area 2. It also runs every 10 minutes, so our average wait time is 5 minutes. Finally, our ride from the connection point to Activity Area 2 is 10 minutes. So our average trip time is:

Wait 5 minutes

+ Ride 10 minutes

+ Wait 5 minutes

+ Ride 10 minutes

= 30 minutes.

The Connective Network is faster, even though it imposes a connection, because of the much higher frequencies that it can offer for the same total budget.

As cities grow, the travel time advantages of the Connective Network increase. For example, suppose that instead of having three residential areas and three activity centers, we had six of each. In this case, the direct-service network would have 36 routes, while the connective network would have only six. You can run the numbers yourself, but the answer is that the Direct Service network still takes 35 minutes, while the Connective network is down to only 25 minutes, because of the added frequency.

Common Objections

Lets anticipate a couple of objections to this thinking:

The Modeler’s Objection

If we were actually using travel time as a means of estimating ridership, we would have to consider the widespread view, built into most ridership models, that connections impose a “transfer penalty” in addition to the actual time it takes. These penalties assume that even though people say they want the fastest possible trip, they’ll actually prefer a slower trip if it saves them the trouble of getting out of their seat partway through the journey.

In the above example, for example, a model might assume that although the average trip in the Connective option is faster, the Direct Service option would give us higher ridership, because the Connective option imposes the inconvenience of the connection. The modeler might say that this inconvenience is the equivalent of 10 minutes of travel time, so that the Connective option will really attract ridership as though the trip took 40 minutes instead of 30. This common modeling approach assumes that the inconvenience of transferring is something different to, and separable from, the time that the transfer takes.

There is considerable documentation behind the addition of this kind of factor, but the unpleasantness of the connection experience depends on many details of how the connection works. If two buses or trains arrive on opposite sides of a platform, facing one another five meters apart, with their doors open at the same time, walking out of one and into the other is a pretty low level of inconvenience for most passengers. If the connection involves getting off a bus, crossing a busy street, and waiting for another bus not knowing when it will arrive, the inconvenience is much greater.

So the configuration of the connection matters. Transfer penalties are based on a crude averaging of many different types of connection experience, so good interchanges will reduce these penalties. Modeling assumptions about a “transfer penalty” (as distinct from the time the connection takes) deserved to be scrutinized: What kind of connection experience was used to calibrate the model?

The 9-to-5 Commuter’s Objection

Many people who make regular commutes would object to the way I’ve inferred average waiting times from frequencies. After all, if a particular airline route has one flight a day, that doesn’t mean we have spend half the day waiting for it. We go on with our lives and work, and go catch the flight whenever it is going. Many people do treat commuter service schedules in this way. Even if the bus runs every 30 minutes, they’ll just do other things until it’s due, and then go out to catch it.

However, the average wait is still a valid way of capturing the inconvenience of low-frequency services. For example, if you need to be at work at 8:00 and your bus is half-hourly, you may have to take a bus that gets you to work at 7:35. This means that every morning, you’ll have 25 minutes at your destination before work starts, time you’d probably rather have spent in bed. You may figure out how to make use of this time, but it’s still time you must spend somewhere other than where you want to to be.

Note too that for simplicity we have presented this example in terms of commutes to work, but of course, a good public transport system serves many kinds of trips happening all day. You may figure out how to make use of a predictable 25 minute delay at the beginning of your work day, but it’s much harder to deal with unpredictable 25 minute gaps in the many trips that you need to make in the course of the day, such as while taking a lunch break or running errands that involve many destinations. So all-day frequency still matters.

Other Advantages of Connective Networks

Several factors argue for Connective networks over Direct Service networks.

- Average travel time is better than the worst-case time calculated above. In the Direct Service network, everybody’s trip takes 35 minutes. In the Connective network, two-thirds of the market has a 30-minute trip, but one-third of the market (those still served by a direct route) have an even faster trip.

- The Connective network is made of more frequent services. Frequency makes connections faster but it also stimulates ridership directly, especially when we consider the needs of people who have to make several trips in a day, or who want to travel spontaneously, and who therefore need to know that service is there whenever they need it.

- The Connective network is simpler. A network of three frequent lines is much easier to remember than a network of nine infrequent ones. Marketing frequent lines as a Frequent Network can enhance the ridership benefits of this simplicity.

This last item is so important that I’ll do another post on it soon.

Most transit networks start out as Direct Service networks with relatively little focus on connections, but as the city grows bigger and more complex, connections become more important. In most cases, though, there’s a transition from a Direct Service network to a Connective one, a transition that often requires severing direct links that people are used to in order to create a connection-based structure of frequent service that is more broadly useful and legible.

Helping agencies through this hard step is one of my specialties as a consultant, and while there’s usually a moment in the process where the resistance seems overwhelming, the agencies I’ve worked with are almost all glad that they broke through this resistance, because the result was a network that was much more frequent, and therefore more relevant to the life of the city.

The transfer penalty – and the perceived cost of uncertainty in making connections – are both real and must be measured. Yes many models use gross assumptions – but they can also be calibrated to local circumstances. And adding information systems, and other facilities at transfer points can reduce the perceived cost of transfers. But so many systems design networks – and transfer points – to minimize the operational cost not provide the best service to the passenger – and win new riders.

What is REALLY good for a city is when transfer points are made the centrepiece of good urban design – or “development oriented transit” as Sam Adams calls it. Talking about transportation as though it is a stand alone topic and not one intimately involved in the urban fabric is a good indicator that the writer has not taken the care to study the impact of decision making on how people live. Transport is a derived demand – and currently we demand far too much motorised transport because of our disdain for urbanity. Transit systems need to be seen as part of a much bigger picture of remaking our urban places.

I replied to Steven’s comment here:

http://www.humantransit.org/2009/05/chicken-egg-chicken-egg.html

But the complaint about transfers is not usually about *one* transfer, particularly a well-designed one.

The complaint is generally about *multiple* transfers. Taking two trains (or two buses, or one train and a bus) is not much worse than taking one. Taking three trains starts to get a little annoying, but if they’re high-frequency and the transfers are easy, still not too bad. Taking four trains is pushing it, though still done if the transfers are good — and taking four buses is just unpleasant. Taking five trains is quite unpopular.

This calls for well-designed transfers and an attempt to *limit* the number of transfers. To their credit, this is being done in modern designs by attempting to concentrate transfer points. Gaps such as “arrive in London at Paddington Station, leave from London Bridge, take two Tube lines to interconnect” are not attractive; super transfer centers like Berlin’s Hauptbahnhof are.

The hostility to transfers comes from situations like London’s, or Chicago’s multiple commuter train stations (interconnect by… walking several blocks or getting a taxi. Or taking two buses.)

Well said, it is all a question of trade-offs of travel delay for schedule delay, and how thick the market is. If there is sufficient demand for frequent service, direct routes are better, but until there is such demand, frequent indirect service may be preferable to infrequent direct service. The worse is infrequent indirect service, which will attract almost no-one with an option.

It would help too if the transit vehicle is going a significantly faster average speed than a bicycle, which normal bus service does not. So for me the trip from home to city center, which I can do on one bus that runs more-or-less directly diagonally across town, is as fast by bus as by bicycle if we don’t count the wait for 20-minute frequency service against it. From work to city center, similar. But home to work involves a trip south-east to city center, a long wait, then a transfer to a bus that goes back as far west as my starting point was. Can bicycle direct to work in a third the time, and a car is faster still.

@Nathanael: What’s more, can you imagine the five-train or 4train1bus trip it would take to get to LAX from a place like Fullerton or Sylmar? Los Angeles is admittedly trying to resolve one major piece of the problem by improving its downtown connections, but it’s still hamstrung by numerous connectivity issues.

Great post. I wrote on the same topic a few months ago.

http://seattletransitblog.com/2009/04/28/classification-of-transfers-by-headway-length/

You might also enjoy

http://www.amazon.com/Urban-Transit-Operations-Economics-ebook/dp/B000UOJZD4/ref=sr_1_2?ie=UTF8&s=books&qid=1247294072&sr=8-2

It was the book we used for my transit planning class.

This ignores the fact that transfers can also be missed (and often are). Consider how much more people will pay for a non-stop flight from A-B to avoid having to go through DFW and miss a connection, for instance. (The airlines have noticed!)

Of course, the penalties for missing a transfer on a mass-transit system, and missing a scheduled flight due to a delay, are quite a bit different. One is frequently measured in minutes, the other in hours.

Likewise, I’d deal with a 30-minute delay on a missed flight when I fly every month or two on business. I would not tolerate a 30-minute delay due to a missed connection very often on a daily commute. Especially if I own a car that I can go back to.

In the German-speaking world, transfers are timed, and trains stick to schedule, so you can be sure you won’t miss the connection.

Elsewhere, urban rail systems don’t always time transfers, but the waiting times are still short because of the high frequencies. For example, Singapore’s central transfer station doesn’t offer timed connections, but trains run every 6 minutes even off-peak, so missing the connecting train isn’t a big deal.

Thanks, Alon. Yes, my example above was specifically about high-frequency transfers, and the fact that with a limited budget, you need to require the transfer to build the frequency. Note that the travel time estimates in this post are average. If you just miss a connection, the waiting time at the connection is 10 minutes instead of 5, still no slower than the low-frequency, direct-service option.

It would be nice if the ‘new transit’ cities were talking about building rail networks with frequencies like the ones you and Alon are talking about.

They’re not.

They’re building commuter rail at 30-minute headways, or, at best, light rail at 15-20 minute headways. The transfers, if they exist, are to other light rail lines at 15-20 minute headways, or to awful city bus service.

Let’s be real here – in THAT environment, you’d better make sure that first rail line delivers a direct ride for most riders or you might as well not even bother.

(And starting those systems as ‘shorter, multiple, high-frequency’ is not an option – I’m referring to cities like Dallas, Seattle, Austin, etc here – many are assuming lots of transfers AND high headways, in other words – like Austin’s idiotic Red Line).

M1EK: what you’re saying is that those transit builders are incompetent, so they couldn’t implement competent solutions well. In either case, the response should be to dump the local planners and replace them with people who know what they’re doing.

When the system is run well, you can time transfers. When it’s built well, the first line will be an urban rail spine extending in both directions from the CBD, maximizing ridership and minimizing operating costs; the suburban lines will come later.

It’s not that hard. Calgary did it right, and got the busiest light rail system in North America out of it.

No, Alon, I’m saying that the transit planners operate in the real world – where designing a high-frequency multi-line rail system is not politically or economically feasible.

The choice is either between a good light rail line that carries its own weight without requiring a bunch of transfers, or a bad rail line that forces everybody through one or more ‘intermodal’ centers, usually on to buses.

You can’t time transfers on to / off of city buses. South Florida learned this the hard way.

Great post. What do you think about “timed” transfer centers? My city has had them since the County absorbed our city’s transit authority thirty years ago. We, the riders, find them to be dead, desolate, uncomfortable and disconnected suburban areas where there is practically no transit service outside of the half-hour pulse. They cause excessive travel time, mainly because the transfer areas aren’t central, they’re mainly on the periphery.

Some effort, like you’ve said, should go into making transfer areas easy to navigate, but one additional point might also be to have such places where one can get some use out of “wait time” to run errands: to buy a few groceries, to get a cup of coffee, etc. in cases where one inevitably misses a connection.

Pierce Transit could use some of your expertise. They’re in the middle of redesigning the system thanks to a change in leadership and constrained sales tax revenue. If you could take a look at the network, I’d be grateful for any thoughts you might have about it. Heck, maybe the board could even hire on as a consultant. You’ll find more information at http://PierceTransit.org It’s the second-largest public transit agency in Washington State.

I forgot a long time ago to post this; please forgive me.

Austin’s Red Line, which requires most potential passengers to transfer to a dedicated shuttlebus to get to their final destination in all of the major activity centers in the core, has seen ridership drop off a cliff since revenue service began:

http://mdahmus.monkeysystems.com/blog/archives/000652.html

Just today, the city’s urban rail election (which actually would carry tens of thousands per day rather than the 400 the Red Line is now hauling) was pushed off to 2012 at the earliest because the Red Line has destroyed momentum for rail here:

http://mdahmus.monkeysystems.com/blog/archives/000653.html

So sometimes, in fact, transfers aren’t good for you and your city; sometimes they’re the death of future transit service, in fact.

One major assumption with Jarett’s “connective” model is that it assumes that the transfer point is always on your way, that is, passing by it won’t add any time beyond the overhead of the transfer itself.

In reality, this assumption is very often not true. Consider Jarett’s own example (assuming his map is drawn to scale). A trip from residential area 1 to activity center 1, or activity center 1 to activity center 2 would require traveling a very circuitous route just to pass through the transfer center. The difference in travel time between the “direct” option would be far more than the wait for the second bus, especially if these are slow buses with frequent stops, operating in mixed traffic.

I’ve seen numerous examples of systems in which buses take excruciating detours so that all buses that serve an area meet at a single point. This makes travel extremely slow for anyone passing through the transfer point, regardless of whether or not they actually have to transfer. To make matter worse, the millions of dollars that get spent to construct the transit center in the first place reduce money available for operations, resulting in lower frequencies and an even worse experience.

I agree more with Jarrett on transferring. In my city, I can go to a major shopping center by either a direct line or by transferring. But I prefer to transfer because the direct line runs infrequently, while two other lines that run more frequently can get me to the center sooner than if I had to wait for the direct line.

Maybe our city is unique (Granada, Spain), but the system works pretty well by having all the buses go to the main street (closed to cars BTW), where you transfer to another bus if needed. To me, one bus transfer is fine. Two is best avoided! Madrid metro on the other hand is way cool. Probably only a 2 minute headway on most lines! I don’t know why anyone would bother to drive in Madrid.

While I agree with Jarett here, on the advantages of connections, when done right, I’d like to play Devil’s advocate here and state a couple of objections that I haven’t seem fully addressed:

1) Jarett’s model assumes that expected wait time is half the headway. This looks great on paper, but the ability for this to actually happen depends on every bus sticking precisely to it’s posted schedule to actually achieve the desired headway. In practice, as we all know, buses tend to get bunched and when they get bunched, the average wait the customer experiences is often significantly larger than half the headway.

2) Jarett’s model is also based on the assumption that minimizing expected travel time is the objective. However, it is also important to minimize the risk of encountering a lengthy delay. After all, if you have to be somewhere at a certain time, it’s the worst-case travel time, not the average-case travel time that determines when you need to leave home.

In Jarett’s own model, the worst-case travel time with the connective model (assuming wait time = full headway) is 40 minutes, rather than 30 minutes, worse than the direct-service model.

Furthermore, any time you wait for a bus, you assume a certain risk that something happened before the bus got to your stop causing a lengthy delay. If the wait happens twice, you have double the exposure to such risk. For example, if each bus has a 1% chance of arrive more than 30 minutes late, the connective approach gives you a 2% chance of a 30+ minute delay, rather than a 1% chance with the direct service approach.

I believe the perceived reliability issues go at the heart of the problem of why so many people are reluctant to embrace a connective approach – in order for a connective approach to work, you have to be really sure that all services involved can be trusted to arrive at their appointed time. If people don’t place complete trust in their transit agency to provide reliable service, they will always favor the direct service approach because it minimizes risk.

One point missed above is that in the Direct Service Option, there is no allowance for travel between Residential 1, 2, 3 or between Activity Centres 1, 2, 3. If they had been included and the total were still at 30min frequencies, then in terms of Trip Length | Frequency | No. Routes that’s 20min | 30min | 12routes = 35min average journies or 10+10min | 7½min | 3routes = 27½min average journies measuring from a random arrival time.

I just wish they would use connections in Brisbane. Bit of a furore over new bus routes going in at the moment.

http://www.brisbanetimes.com.au/queensland/calls-for-bulimba-glider-rejected-20120201-1qtbt.html

I used to work for a system that relied heavily on transfers. The system was configured around timed transfers at transit centers, precisely the type of network you called for.

The transfers were relatively easy to make, but the knock we got was just how slow it was. Making a timed transfer work, especially mid-route, added a significant time penalty into the route. Depending on the trip in quesiton, it also added off-direction travel.

In your simplified example above, you assume that the moving time of the trip was the same. We did not usually find that to be the case. A quick examination of your hypothetical map ahd the length of the lines shows this as plausible in your scenario as well. That could eat-up your five-minute saving pretty fast.

I agree with your basic premises:

Transfers are not the end of the world

In a resource constrained world, you have to make trafe-offs.

Every transfer is not the same and there are things you can do to make them less of a barrier.

However, in your list of ojbections, you miss the one we heard the most.

However, I would design the “Connective Option” a little different, namely in such a way that each of the three lines connects with the other two lines in two separate transfer stations instead of one mega station that connects all of them together like in your example.

I would offset each line a little, just like the Czech have done in Prague (focus on the center of the system, you get three transfer stations instead of a single megalithic station that people will only hate): http://de.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Datei:Prague_metro_plan_2008.svg&filetimestamp=20081121174523

If you weave the tracks at each transfer station in the right way you will also get the benefit of “same platform transfer to the other line” which is impossible if it is a single station serving all transfers.

While I generally agree with the “transferring can be good for you idea”, there is a flaw with the analysis you provided on your hypothetical example. You claimed that with 1/3 the routes, they can run every 10 minutes rather than every 30 minutes, ceteris paribus (the same number of buses, and presumably the same average speed). The problem is, the average route length in your hypothetical example with only three routes is longer than the average route length in the nine route scenario. So headways wouldn’t be quite cut by 2/3 if the same number of buses are running the same averge speeds.

Brisbane has route 369 which is a cross town bus service placed into operation about 6 months ago. It runs every 15 minutes for the better part of the day.

Unfortunately, patronage on this route seems terrible, listed here TransLink>Bus Review>369 http://translink.com.au/ despite good anchors at either end and intersection with multiple bus routes.

This discussion absolves city planners of their responsibility. If the three activities are co-located in three dense urban residential areas only one frequent direct connection with one stop in the middle would suffice.