What if we planned public transit with the goal of freedom? Well, it’s hard to improve things that you can’t measure, but now it’s becoming possible to measure freedom, or as we call it in transport planning, access.

Access is your ability to go places so that you can do things. Over the last few years, I’ve come to believe that may be the single most important thing we should be measuring about our transport systems — but that we usually don’t.[1] Access isn’t a new idea, but as our data gets better it’s becoming easier to measure, and it could potentially replace many other measures that are groping toward the idea but not quite getting there.

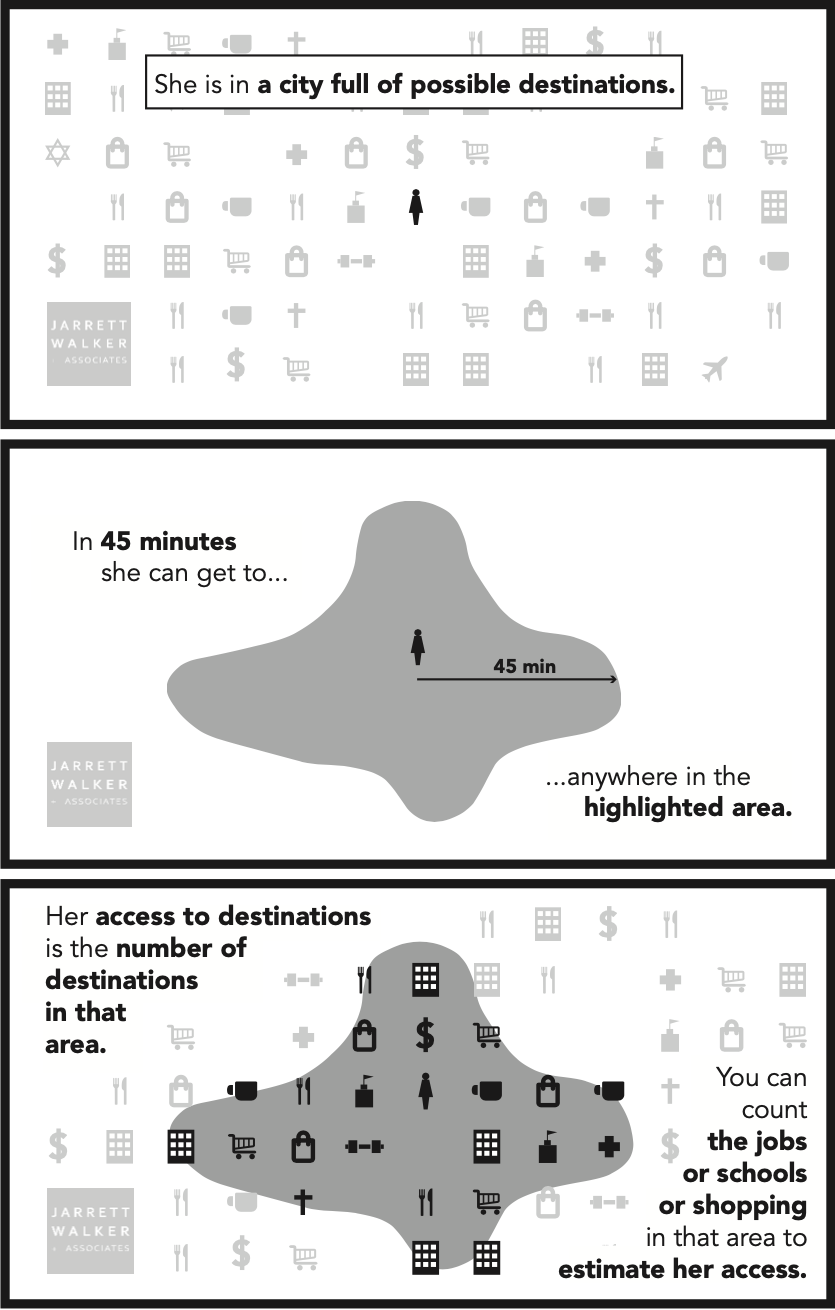

We calculate access, for anyone anywhere, like this:

Whoever you are, and wherever you are, there’s an area you could get to in an amount of time that’s available in your day. That limit defines a wall around your life. Outside that wall are places you can’t work, places you can’t shop, schools you can’t attend, clubs you can’t belong do, people you can’t hang out with, and a whole world of things you can’t do.

We chose 45 minutes travel time for this example, but of course you can study many travel time budgets suitable for different kinds of trips. A 45 minute travel time one way might be right for commutes. For other kinds of trips, like quick errands or going out to lunch, the travel time budget is less. For a trip you make rarely it might be more.

But the key idea is that we have only so much time. There is a limit to how long we can spend doing anything, and that limit defines a wall. We can draw the map of that wall, and count up the opportunities inside it, and say: This is what someone could do, if they lived here.

Access is a combined impact of land use planning and transport planning. We can expand your access by moving your wall outward (transport) or by putting more useful stuff inside your current wall (land use). We can use the tool to identify how much of a place’s access problem lies in the transport as opposed to the development pattern.

We can calculate access for any location, as in this example, but we can also calculate the average access for the whole population of any area. In the first draft of our bus network redesign for Dublin, Ireland, for example, we found that the average Dubliner could reach 20% more jobs (and other useful destinations) in 30 minutes. To discuss equity, we can also calculate access for any subgroup of the population: low income people, older or younger people, ethnic or racial groups, and so on.

Why Access Matters

People come to public transit with many goals that seem to be in conflict, but it turns out that a lot of different things get better when we make access better:

- Ridership tends to be higher, because access captures the likelihood that any particular person, when they check the travel time for a trip, will find that the transit trip time is reasonable. Ridership goes up and down for all kinds of other reasons, but access captures how network design and operations affect ridership. [2] In our firm’s bus network redesigns, we’ve been using access as a key measure of success for about five years now, and it consistently leads us to ridership-improving network designs.

- Emissions and congestion benefits all improve, because they depend on ridership, which depends on access.

- Economically, the whole point of a city is to connect people to abundant opportunities. People come together in cities so that more stuff will be inside the wall around their lives. When we measure access we’re measuring how well the city functions at its defining purpose.

- As for equity or racial justice in transit, well, isn’t equal access to opportunity at the core of what these movements are fighting for? Access describes the essence of what has been denied to some groups through exclusionary development planning and exclusionary transport planning, so it helps us quantify what it would mean to fix those things. This, in turn, could help justice struggles avoid a lot of distractions. Because in the end, access is …

- Freedom. Where you can go limits what you can do. If we increase your access, we’ve expanded the options that you have in your life. Isn’t that what freedom is?

When we improve access, with attention to who is benefiting most, we improve all of those things. It’s this remarkable sweep of relevance that makes access analysis so interesting and potentially transformative as a way to think about transportation.

Access Compared to Common Measures

Most methods for studying or improving transit assume that we should care about (a) what people are doing or (b) what people want to do.

Data about what people are doing includes travel behavior data, which are the foundation of much of the accepted methods of transport planning. In public transit, ridership data is in this category. Ridership is the basis for transit’s benefits in the areas of congestion and emissions, and also of fare revenue.

However, what people are doing isn’t necessarily what people want to do, or what they would do if the transport network were better. Much of what people do may just be the least-bad of their options given the city and transport network as it is. This problem leads to various methods of public surveying to “find out what people want,” in some sense. But there are lots of problems with that, mostly lying in the fact that people are not very good at knowing what they’d do if the world were different in some major way.

Access takes us outside of both of those frames. Instead of asking “what do people do?” or “what do people want to do?” it asks “what if we expanded what people can do?”

Access analysis does not try to predict what you’ll do. In fact, it doesn’t need to predict human behavior at all, which is a good thing because human behavior is less predictable than we’d like to think. Access calculations are vastly more certain than almost anything emerging from social science research, because they are based almost entirely on the geometric patterns of transport and development. [3]

Instead, access starts with one insight about what everybody wants, even if they don’t use the same words to describe it. People want to be free. They want more choices of all kinds so that they can choose what’s best for themselves. Access measures how we deliver those options so that everybody is more free to do whatever they want, and be whoever they are.

What Access Analysis Can’t Do

Will access analysis of transit put the social sciences and market research out of business? Of course not.

- We need to understand how different users experience public transit, and how the experience can be better designed to meet those various needs.

- We need to know exactly who won’t be served by access based network design so that we can decide what actions to take for those people, if any.

- We need to keep exploring the relationship between access and ridership so that we can identify the factors that sit outside that relationship and must be considered.

- Access analysis would also become more powerful if we had better data on the locations — to within 1/4 mile (400m) or so — of various non-work destinations: retail, groceries, medical, and so on — so that we could better assess people’s ability to get to such places.

But in 30 years of listening to public comment, I’ve heard enough times that people want to go places so that they can do things. So let’s measure how well we’re delivering that, and let’s ask ourselves if that’s more important that some of the things we measure now.

Further Reading

This post could have been much longer; in fact, I hope it will become a book. Meanwhile, here are some great resources:

- The 2020 Transport Access Manual is the first comprehensive explanation of access and how it can be applied to various questions. It’s the work of a team led by professors David Levinson (University of Sydney) and David King (Arizona State University). Full disclosure: I had a role and wrote some snippets.

- The University of Minnesota’s Accessibility Observatory, founded by Levinson and now led by Andrew Owen, is one of the main research centers on the topic. For several years they’ve been publishing Access across America, an atlas showing where people can get to from various places by car, transit, etc..

- On the philosophical issues about freedom vs. prediction, and why it’s important to separate physical knowledge from social science knowledge, see my fun Journal of Public Transportation paper, “To Predict with Confidence, Plan for Freedom.” Seriously, it’s fun.

- On what high-access public transit tends to look like, here’s a fairly evergreen 2013 post of mine, with downloadable handout, on how some of the big debates of transit planning line up with a goal of high access for a community.

I will update this post with further links.

Endnotes

[1] In the academic literature, what I’m calling access is usually called accessibility. Both of these words have contested meanings, because both have been used specifically to refer to the needs and rights of people with disabilities. I follow the recent Transport Access Manual in using access as the less confusing of these two words. Of course, we are talking here specifically about spatial access — the ability to do things that require going places — which is not the only kind. However, a lot of the ways that people are cut off from opportunity do turn out to be spatial. Transportation (i.e. access) is a major barrier to employment in the US, for example.

[2] This paper, for example, establishes a relationship between transit access and public transit’s mode share, one that is especially strong for lower income people.

[3] There are exceptions. Traffic congestion, for example, is a human behavior that affects the access calculation.

15 minutes travelling time is far more reasonable.

Every transit trip entails some amount of walking and waiting, so it is nearly impossible for a trip involving transit to be, door to door, under 15 minutes. Even in dense cities with world class transit systems, where most people do not have cars, the vast majority of sub-15-minute trips are walking trips that don’t involve transit at all. While it make be theoretically possible to wait for a bus to go 1/4 mile, in practice, it is nearly always faster to just walk.

So, in order for transit to be useful, you have to allow for a larger travel-time budget, on the order of 30 or 45 minutes.

There are lots of transit trips that are 15 minutes. Walk five minutes, wait five minutes, take a bus five minutes (e. g. https://goo.gl/maps/iRmMUxXJsNirg5EFA). This is not a short trip (it is 1.4 miles). A lot of buses go that fast, especially if they have international stop spacing and/or off board payment (both of which are become more common in North America). The most common weak point is frequency.

The isochrone maps typically don’t include the initial walk. The same is true for driving — they don’t include the time it takes to find your keys, open the garage door, scrape the frost off the windows, etc. Neither include the time it takes to get out of a building, which is significant if you work in a skyscraper. The numbers are based on time from a particular spot on the street — typically next to a bus stop.

Some of the icochrone maps ignore frequency. Good ones incorporate this. It makes sense to include different ranges within the maps. This map does exactly that, showing 15, 30 and 45 minute ranges: https://urbanist.typepad.com/.a/6a00d83454714d69e201b7c78730ae970b-popup. The 15 minute range is very important — arguably a lot more important than the 45 minute range. That doesn’t mean that the trip, end to end, will take 15 minutes or less, but it means that once you get that to that bus stop, it will.

Right, but in practice, the “walk 5 minutes, wait 5 minutes, ride 5 minutes” is more what you see in an idealized trip rather than a real trip.

Occasionally, it’s possible to get lucky and find an express bus that just happens to stop right by your origin and destination that makes a 15-minute transit trip possible. Here’s one example I was able to take advantage of a few years ago during a visit to San Diego (https://goo.gl/maps/nbX6w1ELCkFygJi59). But, it’s important to understand that trips like that are the exception, rather than the rule. The fact that there just happened to be a bus that stopped right by my hotel, hopped right on the freeway, and dropped me off a block of way of where I wanted to go, was shear luck. And, even with all that luck, the door-to-door travel time just barely clears the 15-minute hurdle. And even then, there’s still the wrinkle that the bus in question only runs every 30 minutes, so if the schedule didn’t work out, I would still find myself walking up or down the hill.

Your example showed an idealized version of a 15-minute transit trip where the origin and destination happen to fall along the same street, served by a frequent bus. But, even then, it’s a 15-minute transit trip only because the distance between the origin and destination happen to fall within a very precise, narrow range. And even then, Google Maps doesn’t account for the wait time, which can be up to 15 minutes.

Thinking through my actual trip history the past several years, I’ve made a ton of walking trips in under 15 minutes and a ton of transit trips in the 15-45 minute range. But the number of trips involving transit that were door-to-door under 15 minutes were vanishingly rare. There were several trips where I technically could have done that if I really wanted to, but it was faster to just walk.

If you look closely at the link you provided, it doesn’t include any time budget waiting for the #5 bus. The entire 10 minutes is just walk/ride/walk. That’s not realistic. Even if we assume that you get to choose when to leave to match the bus schedule, you still have to budget a minimum wait time of 5 minutes or so; otherwise, your time budget is based on arriving at the bus stop right as the bus is pulling up, and risking missing it.

With a 45-minute time budget, this distinction doesn’t matter much, but with a 15-minute time budget it matters a great deal. Simply by involving the bus at all, a minimum 1/3 of your time budget must be allocated to waiting at a bus stop – not including the walking and riding portions of the trip where you’re actually moving.

Throw in the walk time, the trip you showed just barely fits within a 15-minute time budget – with the trip just 1.4 miles in total and the final destination being right next to a bus stop. In other words, with a 15-minute time budget, the best transit can reasonably be expected to do is to allow you to cover 1.4 miles in 15 minutes, the equivalent of a medium-pace jogger.

Another way to think about it – with a 15-minute time budget, the isochrome showing where you can get to by walking only and the isochrome showing where you can get to by a combination of walking and transit aren’t really all that different. Sure, the walk+transit map is a little bit larger than a walk-only map, but not that much larger. And it’s all within a range where, even if there were no transit, you could extend your range similar by just increasing your human-powered-moving pace. For instance, starting from the point you indicated on the map, a jogger using only their feet would probably have a larger 15-minute isochrome than someone restricted to 3 mph walking+transit.

That is why to make the impact of transit meaningful, you need a larger time budget. A larger time budget allows for longer trips which allows the faster speeds of a bus to overcome the overhead of accessing it. Similar to how with a time budget of around 3 hours, access to airplanes and airports doesn’t improve your isochrome much, if at all, over what you can get with only a car – by the time you drive to the airport, park, go through security, etc., it’s not worth it anymore.

Of course, there are always exceptions, particular for trips that start and end very close to some very fast transit, such as commuter rail or an express bus. For example, here’s an example of a 16-minute transit trip in San Diego (https://goo.gl/maps/oFLDZq2ERVNL4hBn8) that would take an hour and a half to walk if there were no transit. But, that only comes close to fitting the 15-minute bucket because the origin and destination just happen to be served by an express bus (the #20) that hops on the freeway and makes almost zero stops in between. In practice, if the origin and destination are chosen at random, the liklihood of your trip just happening to line up with an express bus that well is very, very slim. A 45-minute time budget, on the other hand, makes that express bus far more useful because you can now use it to get between anywhere up to a 15-minute walk from the downtown stop and anywhere within a 15-minute walk of the Fashon Valley stop. That’s a much larger set of origin-destination pairs.

400 m, 1/4 mile .. all good and a reasonable radius for walking.

But call it “about 500 steps” and a bunch of people that don’t know how far 400 m is (Americans, mostly) or 1/4 of a mile (also Americans, mostly) will say “Oh, I try to get 10,000 steps every day and 500 is only half that!” (again, Americans). Might be worth adding to slides.

Measuring access is one of those nice concept that really takes a bunch of things that seem only somewhat related and makes it all one concept, and an easily understandable one at that. Good work!

It is also common for people to think in terms of walking time, not distance. 400 meters, or a quarter mile, is about a five minute walk. Thus you can say “less than a five minute walk” to the destination, which just about everyone would consider fairly close.

That is the difference between public communication and measurement. Time spent walking does vary between people, so to do the calculation you have to use distance. As a healthy and tall adult I can probably cover 400m in three minutes, not so when my small kids were walking with me, nor what a senior can do. But when presenting a plan, referencing “average” walking time is likely a good way to make things easier to understand.

“Access analysis would also become more powerful if we had better data on the locations — to within 1/4 mile (400m) or so — of various non-work destinations: retail, groceries, medical, and so on — so that we could better assess people’s ability to get to such places.”

I think you may be able to parse out some of that via census data. The reports not only show where people are working, but what type of work they are doing. If nothing else, you could come up with a rough “multiplier” for each type of employment. For example, if there are a lot of people employed in retail on a block, then chances are, lots of other people are visiting there. It may be that there is a big grocery store, or lots of little shops, or a bunch of night clubs. No matter what, each one will employ people who serve people (the nature of retail work). Thus there is a big multiplier for that type of work. At the other end of the spectrum is manufacturing. A large manufacturing firm does have occasional visits, but not that many, other than folks who are handling large amounts of stuff (which doesn’t transport well on a bus). You could probably do studies on employment (by looking at a sampling of the visitations) to get a better idea of the multiplier.

There are other issues, of course, but those get more complicated. For example, unless you worked there, you aren’t going to go to the 7-11 across town if there is one down the street. Except maybe if you are just visiting someone.

This also has to be considered. A lot of trips are just personal visits. Connecting high density residential areas to high density residential areas will lead to good ridership numbers, regardless of how many other attractions there are.

This is why this approach shows a lot of promise. It errs on the side of assuming that everyone wants to go everywhere, which is the opposite of a lot of traditional North American transit, which is largely based on getting to work (or maybe to school). If I see an isochrone map around a high density area, and the 15 minute color covers a huge part of the city, I know I want that. My guess is so does everyone else.

Ross. We’ve found that data disappointing. It’s sample size is much smaller and it’s statistically meaningful only at zones that are too large for the intrinsically fine-grained work of transit access analysis.

The search for a COVID vaccine has also underscored the importance of access, as described in this post. If you want a vaccine soon (e.g. within the next month), you probably can’t afford to be picky about the time or place that you get it, and the place that has vaccine for you the soonest is far more likely to be some exurban medical clinic at the opposite end of town than the local pharmacy down the street.

A transit network focused on trying to connect people to very specific places is unlikely to work for this sort of problem, the practical effect being that getting a vaccine mostly requires either a car or knowing someone to drive you around, and may be partially responsible for the racial disparities we are seeing in vaccine rollout. On the other hand, a transit network focused on maximizing the number of places you can get to in 30, 45, and 60 minutes – all day long – gives someone without a car a fighting chance of getting where they need to go in a reasonable amount of time, without having to wait weeks or months for an opening somewhere closer.

Access can be greatly reduced by operational incompetence. In a very large Florida county (Broward), I know of routes that are consistently and reliably inaccessible for hours at a time. They are inaccessible because 1) The passenger capacity of the route’s assigned bus type is far below actual passenger demand, 2) The transit system has a set of spare buses which are deployed ONLY in response to electromechanical breakdowns, and 3) Any “Bus Full” condition, even if it is well known to block all passenger access along long stretches of the route during a consistent set of hours each and every day, is simply ignored by the transit system. These affected passengers all have access envelopes of ZERO diameter. They only get to stand there and watch in the Florida heat and humidity as bus after bus (1 every 30 minutes) refuses to stop to pick them up. Any passenger naive enough to actually depend on the bus to get to work will be promptly fired due to never showing up for work on time.

Never confuse incompetence with lack of money. I’m not sure what the proportions of those are in your case, but it sounds like it’s a mix.

This may sound crazy, but where I live (Alexandria, Virginia) it’s not just a question of how far you can go in 45 minutes but how long it will take to get back. With planning, riding the only bus on our street (which mostly runs once an hour) we can travel as far as the bus goes in 35 minutes (about 5 or 6 miles: not too bad); we have to be outside a little early because sometimes the bus is early, sometimes it is late, and sometimes it doesn’t come at all. (And I can’t rely on the Metro information. When I went for my second Covid shot, it was snowing, and the Metro website said that all bus lines were running smoothly, but I didn’t see a bus all morning. I called Metro and learned that the southern few miles of our bus line were not being served at all.) Walking half a mile to other streets and waiting for a bus takes at least 20 minutes, which still gives us a range of more than three miles. Those options require leaving home according to the bus schedule. But when you’re ready to go home, it might be half an hour or even an hour till the next bus, in which case we can’t go anywhere in 45 minutes. We try to plan grocery shopping to return home in rush hour, but we still sometimes have to wait half an hour, and like those people in Florida, I’ve been left standing in the heat (last summer, with groceries) because a driver wouldn’t let me on.

We were able to get the Covid vaccine by going to vaccination centers by bus. To get hers, my wife had to take two buses to go about three miles as the crow flies, and it took an hour to get there. To get mine, I had to go seven miles, using two buses and walking half a mile, and it took an hour and a half. Getting home took much longer because I waited the better part of an hour for the buses. We are retired, so we can afford to spend hours waiting for and riding buses, but it’s not our first choice of how to spend our time, and a lot of people cannot afford the time.