Access is your ability to go places so that you can do things. In this “basics” article, I laid out why I think measuring access would help advance many important goals that appear to be in conflict, and I suggested, for both practical and moral reasons, that public policy should care about what people can do — i.e. their freedom — as opposed to just what we computer-enhanced elites predict people will do.

Many smart people have offered critiques of this idea, or at least of its practical applications. I’m particularly grateful to Alex Karner of UT Austin and Willem Klumpenhouwer of University of Toronto for this conversation, and to Matt Laquidara, who laid out a very thoughtful critique early on. Please point me to others that I may not have seen.

Two Kinds of Critique

First, let’s distinguish between rhetorical and investigative uses of analysis. In my practice as a consultant, I’m trying to break through into a public conversation, and I’ll do this only with simple explanations of things that obviously matter to people. It’s not wrong for me to oversimplify to make the idea visible and convey its importance. The work can be accurate, as far as it goes, and still be simplified.

So there are two kinds of objections to my thesis:

- those that undermine the fundamental claims of access analysis and

- those that add nuance that could make access analyses more accurate, precise, and/or more relevant in edge cases.

The latter, of course, are not objections at all. They’re just avenues for further development. You’ll see a lot of these throughout this post.

My claims for access analysis

My argument for access analysis is here, but let me quickly list the aspects of my position that seem adjacent to the critiques, and thus most relevant to this response:

- To the extent that we make strong predictions about what humans will do in the future and what outcomes will result, we are assuming that people are not really free. Free people will surprise us. Prediction also appeals to a human desire for control over history that is just not realistic. The future really is unpredictable. (More on this in my Journal of Public Transportation paper here.)

- There are degrees of prediction and the best predictive work makes much softer claims. Prediction of only near-term events, or prediction that speaks only of ranges of probability, is less problematic.

- All analysis is more reliable when it predicts that people will continue to be what they’ve always been throughout history and across cultures. It’s much more problematic assert the permanence of aspects of human society found only in the present, or in the very recent past, or in only one culture (however dominant that culture may be). Again, this is less of an issue for shorter-term predictions.

- Access analysis doesn’t need to be perfect or free of questionable assumptions. It just needs to be much more reliable than predictive modeling. Even if (hypothetically) the two methods turned out to be equal on this score, access analysis would still be preferable because:

- It’s about something that everyone cares about.

- It is correlated to many outcomes that we urgently need our transport system to deliver.

- It is a much more transparent process where the assumptions and their impacts are easy to document, even if they’re controversial.

- When you pile up the assumptions on both sides, access analysis carries a much higher degree of certainty because it isolates geometric, physical, and biological insights and relies on them to the greatest extent possible.

So let’s look at the biggest doubts about access analysis.

Is it good only for commute trips?

Our firm‘s analyses usually focus on trips to work or school, and people routinely object that those aren’t the only kinds of trips. Of course they aren’t. They aren’t even half of all trips.

However, when we think about the most long-term freedoms we need, the freedom to construct our lives and commitments according to our values, the commute (work and school) looms large. Your ability to hold a certain job, or study at a certain school, will do a great deal to define the capabilities you’ll develop, the money you’ll earn, the social networks you’ll be part of, and so on. Those things, in turn, will create the conditions for the freedom or unfreedom that you’ll experience down the line. So when we seek to quantify freedom in the broadest sense, it may be reasonable to put special emphasis on access to work or school.

Commutes are round trips made on a majority of days and that include spending several hours at the destination. They are almost always to work or school. Commutes are easier to analyze than other trips because:

- It’s easy to calculate how many people will value a trip to each destination. While the number of people who want to go to a store will vary with the quality of the store, its competition, and people’s attitudes to it, every job or school enrollment position will be the destination of exactly one resident.

- Data about the location and quantity of jobs and school enrollments are relatively good in developed countries, although there’s still a lot of variation.

- We have a useful rule of thumb about the tolerable travel time for commutes: Marchetti’s constant, the observation that across many historical periods, people have tolerated a one-way commute time of about 30 minutes. This is an example of the principle that if an aspect of human culture been true far into the past and across many cultures, it’s a more reliable basis for positing what freedoms people will continue to value.

Can we look beyond commutes?

But is access analysis good only for commutes?

In our work we do extend the principle to other kinds of trips. In our recent San Francisco work, for example, we calculated access to groceries, low-cost food resources, parks, pharmacies, and medical centers. We have also experimented with more precise pairing of residents and destinations. For example, if we have good data on both income and wages, we can calculate low-income people’s access to low-wage jobs. We can also exclude retired people from the database of people who value the freedom to access work or school opportunities, but include them — or even make specialized calculations for them — when looking at other destinations that tend to matter in a retired person’s life, including groceries, medical, and parks.

When we move beyond the commute, however, the three benefits I listed above are all absent.

- We cannot calculate, for a given person, how much freedom is provided by the ability to go to one park or medical center over another. The tool would be highly reliable for identical destinations, like McDonalds restaurants or whatever, but I think we’d all agree that if you can get to three McDonalds restaurants you don’t really have three times the freedom that comes from being able to get to just one. The freedom value of alternative destinations depends precisely on them being different from another, and we have no hope of abstractly quantifying that value. In San Francisco we inevitably made simplifying assumptions: valuing parks by the acre, for example, and valuing all medical centers the same. For present-oriented analysis you can dig deeper into trip generation patterns, through surveys etc, and refine assumptions, but that works only for analyses meant to be relevant only in the present. This is a genuine weak point for analysis.

- We have lousy data about most nonwork and nonschool destinations. Some of these things change rapidly. Even if we know where they are we usually don’t know their size or intensity.

- It’s harder to assign an acceptable travel time budget for a nonwork and nonschool trip, as I’ll address below, although we can still make educated guesses.

But predictive modeling has all these problems too! Most such modeling relies too heavily on the commute as the primary trip that matters (and on rush hour as the primary time of day that matters). All of the problems of the non-work trip are at best equal for predictive modeling as for access analysis.

Arbitrariness of Time Budgets

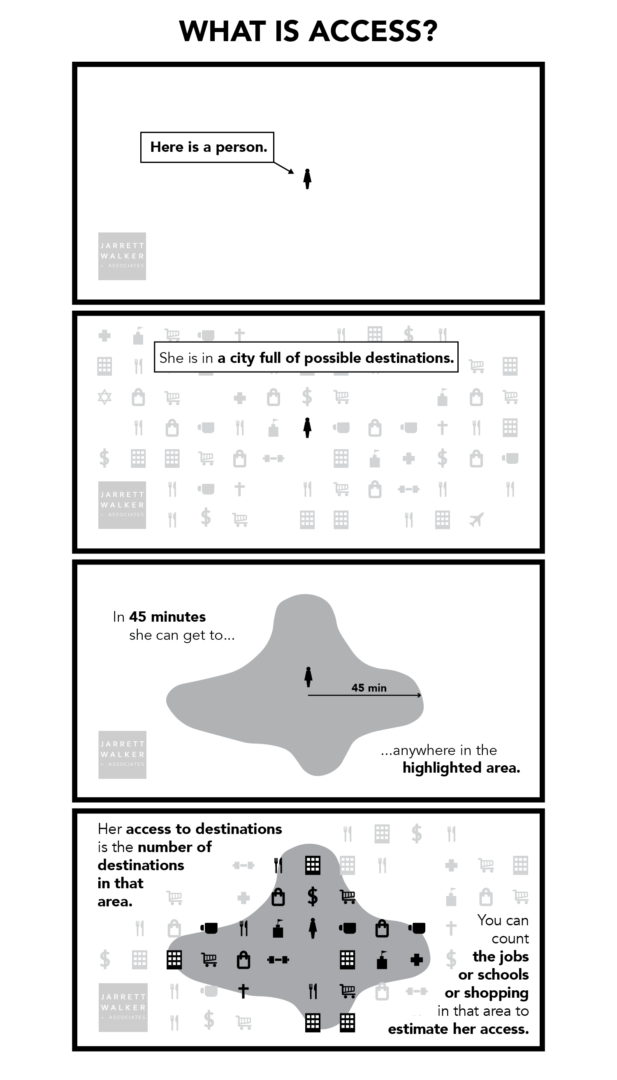

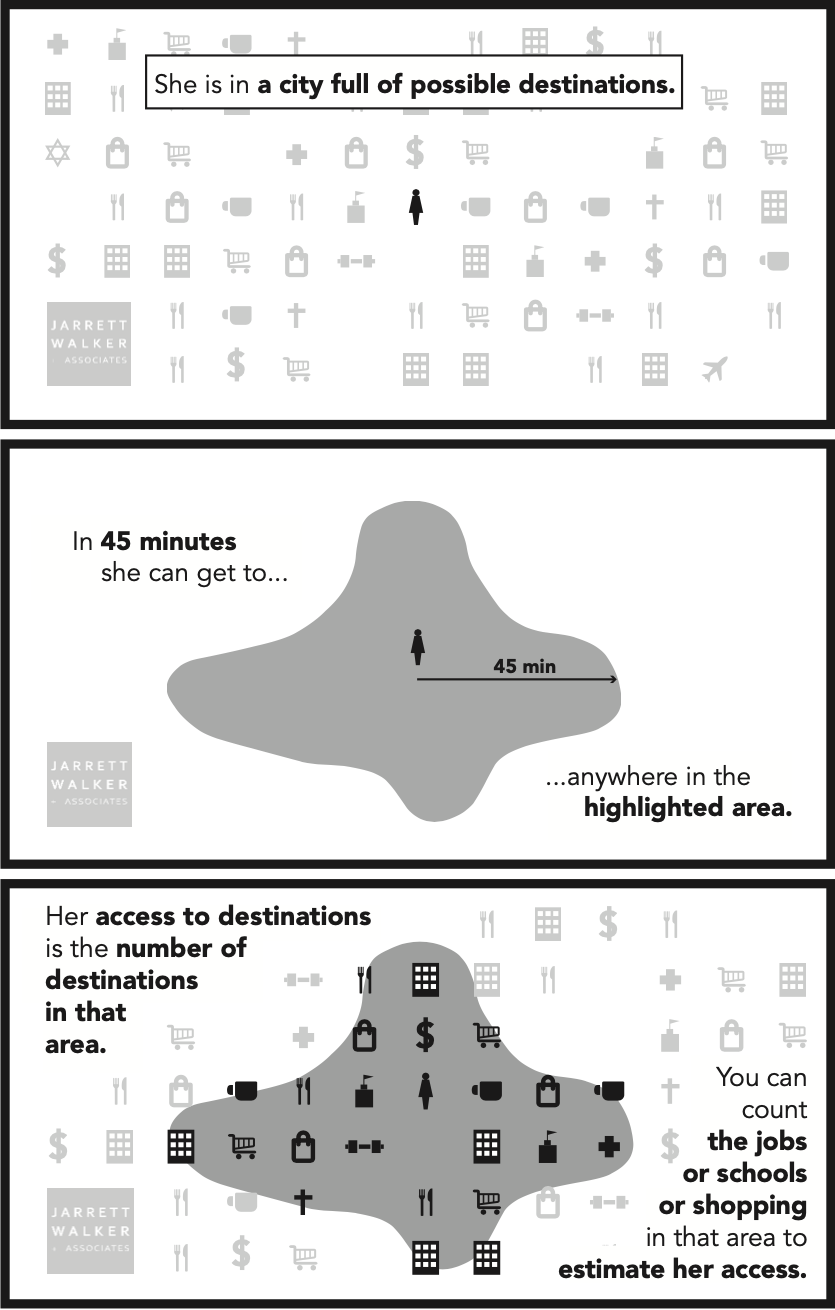

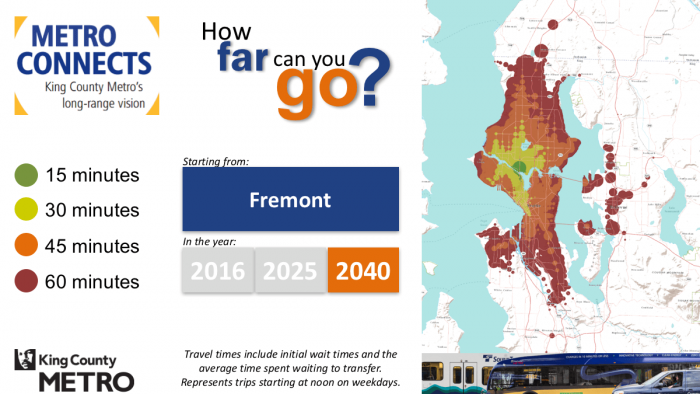

When I explain access, I have to start with the isochrone (see image above), the area that a person at a certain location could reach in a fixed amount of time. Thus, in the access analyses that underlie our reports, we usually describe what area could be reached in 30 minute or 45 minutes.

Why 30 and 45 minutes? If we had twelve fingers I’d probably be using 36 and 48.

There are two problems here: (1) We are imposing an obviously arbitrary threshold, valuing a trip that can be made in 29 minutes but not 31, and (2) We are asserting an amount of time that people find acceptable, which requires an explanation. These are interconnected.

How do we know what travel times people tolerate?

Everybody has the same amount of time. There are 24 hours in everyone’s day. When we perceive a travel time as acceptable it’s because it’s an acceptable percentage of the total time available.

You could argue that the perception of time is different in culturally “slow-paced” as opposed to “fast-paced” places, as in the stereotypes of New Orleans and New York, respectively. On the other hand, setting travel time budgets differently based on the dominant culture of a place is itself oppressive, as more and more people live in places where theirs is not the dominant culture.

Meanwhile, economists like to talk about “value of time,” which is about the value of your time to the economy, not to you. That’s definitely not what we should care about here. We’re talking about an equal right to freedom here, and the only way to do that is to posit an equal value of time.

We can plunge into social science research at this point, looking for non-commute equivalents of Marchetti’s constant. How long do people spend going to the grocery store? How long do they spend going to a park? The data will be all over the place, and it will be hard to separate how long people are willing to spend from how long they are forced to spend given their situation. Again, if we can find something that’s been true longer, and over more cultures, we should rely on it more.

But I think we could start with a couple of principles, which I suspect are relatively transcultural and transhistorical:

- We are willing to spend longer traveling if we will spend more time at the destination.

- We are willing to spend longer making a trip we make less often.

We have a finite amount of time in our day, so if we have many commitments, we’ll need to hold down the total percentage of our day spent in travel. So the commute is likely to be the longest trip we’ll make in a typical day, though we may make longer trips less often. Errand trips, lunch trips etc. are likely to need to be shorter than commute trips.

For retired people, diverse errand trips (medical, recreation, shopping) may be able to take longer than for people who spend much of each day at work or school. We need more research about retired people (and other people who are not in school and don’t have jobs) because their tolerable travel time may depend on the fact that their daily time is less scarce, and that some time-saving actions, like walking further to a more frequent bus stop, carry higher disincentives for them.

I think these principles, buttressed by some research, could help us creep toward some reasonable travel time budgets: Marchetti’s constant (30 minutes one way) for commutes, a lower number for typical errands, but possibly a higher number for retired people. Is this all wildly imprecise? Yes. Is it arbitrary? No, we’re not picking numbers out of the air. We have a sense of the right ranges. Now we come to the next problem: While the roughly correct travel time budget is not totally arbitrary, the exact one we use definitely is.

Why 30 minutes? Why not 31?

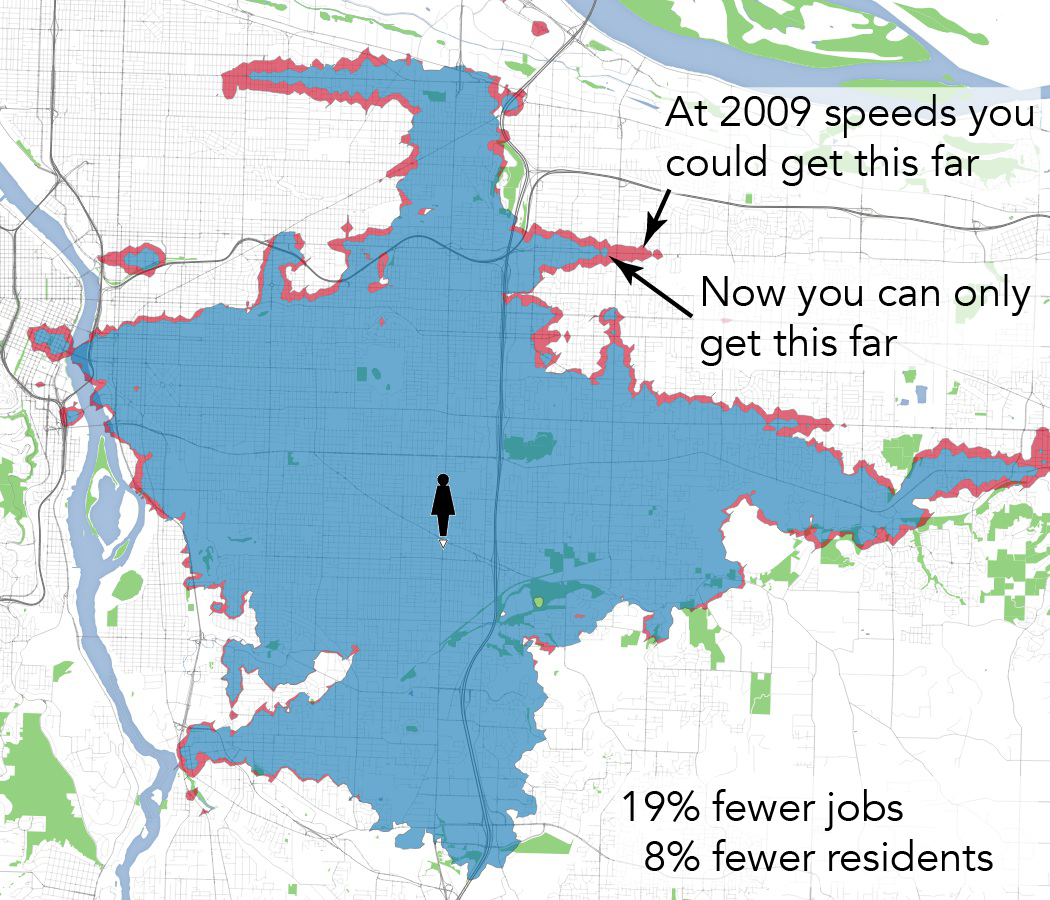

From, our work for Portland Enhanced Transit Corridors project: A person at 82nd & Foster has lost 19% of their 45-minute access to jobs in a decade (2009-19) due to declining bus speeds.

Access analysis starts with an isochrone showing where someone could get to in a fixed amount of time, such as 30 minutes of 45 minutes. But as Matt Laquidara points out, “no one who is willing to take a 45 minute trip is going to consider a destination 46 minutes away totally unreachable.” In a footnote he adds: “Why bound time at all? In theory, it’s possible to have no maximum time and compute the trip duration for every origin, destination, and starting time combination. Those could be aggregated into an average or percentiles.”

Yes, if you could tolerate a given travel time, you could probably tolerate one that’s a minute longer, but you’ll have limits. In growing cities, city bus lines in mixed traffic often slow down very gradually, a classic “boiling frog” event that causes big cumulative damage but never generates a single crisis that would attract attention and action. To a great extent, people who are used to a 45 minute bus ride may accept that it’s 46 the next year and 47 the year after that.

But at some point, they will run out of time in their day. The person whose 45-minute ride is now 55 minutes will eventually give up. They’ll change modes, or quit that job, or do what’s necessary to keep their total daily travel time down. Meanwhile, a new customer who looks up that commute will see a 55 minute travel time, and say no thanks.

So a minute’s difference may not matter, but a 10 minute difference probably does. And to talk about access as freedom, we need to be very approximately right in the travel time budget. Perhaps we’ll get closer if we come up with bell curve of weighted travel time budgets for commutes, maybe peaking at 30 minutes one way but with a long tail stretching upward past 45. This is a reasonable solution to the problem of assigning too much significance to a one-minute difference. But if we get too fancy about how we draw the curve, it takes us back to the same problem. It’s easy to quantify what people are putting up with in terrible situations, but that’s different from what a free person would tolerate. We aren’t describing people’s freedom if we’re relying on data about their unfreedom now.

So some arbitrariness, proudly proclaimed, may be better. For my own rhetorical purposes in presenting and justifying transit service plans, the soundbite and picture take us far: “The average Dubliner can get to 20% more jobs and school enrollments in 30 minutes, and here, let us show how the 30-minute wall around your life changes.” People who hear me say that rarely accuse me of claiming that 30 minutes is radically different from 31. They know I’m making a simplifying assumption so that I can show them something that they can understand, and whose value is obvious to them.

Perils of Aggregation

It’s one thing to analyze all the various kinds of destinations. It’s another more perilous thing to decide how these should be weighed to create a single measure of access. As Matt Laquidara writes:

I’m deeply uncomfortable with most any determination of what locations are important, and consequently, which ones are not. I don’t want to do it myself. I don’t want anyone else deciding it either.

For reasons we explored above, there are always going to be trip desires that are just too scattered, and for which there’s so little data, that they will tend to be omitted in analysis. Residence-to-residence trips are probably one example.

There will also always be the problem that some destinations are hard to quantify. In San Francisco, we assumed that every acre of park was equally valuable in terms of people valuing the freedom to reach it, but of course there are lots of ways to question that, and to introduce other factors such as park infrastructure. Each of those factors would make the measure more precise but also more questionable in terms of how it was projecting some people’s preferences (those who yell loudest at meetings, for example) onto the entire population.

But let’s say that refinements to access analysis make it possible to cover about 95% of trips — or as access analysis would describe it, 95% of the destinations that people will value the freedom to reach. Matt’s objection arises only when we aggregate these different destinations into a single access score. If we declare that one acre of park is worth 0.26 pharmacies, that’s a value judgment. We could try to apply survey data about how much demand each place attracts, which requires assuming that people are making all the trips they want to make. Or we could just stop trying to aggregate, which I prefer. The elected and public audiences with whom I speak usually want to hear separately about each destination type, because each is the basis for a different kind of story and has a nexus with different kinds of public policy. If you care about food security, look at access to groceries. If you care about how much exercise people get, look at access to parks. And so on.

To sum up

- Access analysis is not perfect but can be more reliable than predictive analysis, if only because it makes a more modest claim.

- Predictive modeling requires all the assumptions that access analysis requires, but adds even more assumptions about how human behavior in the future will resemble that in the recent past. Access analysis does not need to include such perilous assumptions.

- We can describe access for commutes with relative confidence. Commutes are a minority of trips but there are a variety of reasons to consider them important.

- Non-commute trips are important but harder to analyze. Still, there’s a basis for making some reasonable assumptions.

- Further work is needed on how to think about freedom of retired people, and more generally about how people’s tolerance for travel time varies with the competing demands on their time. Up to now I’ve been using busy people as the primary frame of reference. This probably contains a bias: I want transit to be useful to busy people, not just to people who enough time that they don’t feel constrained by slow service. Most people are busy.

This post is out there to start arguments, though I hope it also resolves a few. I am not an academic scholar, but I do feel confident in what I asserted in the “my claims” section above, at least until I read the comments, as you certainly should. Then, I may add some updates here.