The Vancouver metro area has now reached the climax of a frenzy of orchestrated rage directed at its transit agency, TransLink. Over 60% of voters have rejected a sales tax increase for urgently needed transit growth, largely due to an effective campaign that made the transit agency's alleged incompetence the issue.

The Vancouver metro area has now reached the climax of a frenzy of orchestrated rage directed at its transit agency, TransLink. Over 60% of voters have rejected a sales tax increase for urgently needed transit growth, largely due to an effective campaign that made the transit agency's alleged incompetence the issue.

There's just one problem. TransLink is (or was) one of North America's most effective transit agencies. Parts of the agency had made mistakes, and of course TransLink was struggling to meet exploding demand in one of the world's most desirable metro areas. Almost nobody defends TransLink's governance model either. But TransLink is, or was, an effective network, run by a reasonably efficient agency. For years I cited it all over the world as a model for good planning. Whether it remains that depends on how much of it is now destroyed in the thrill of recrimination.

Admittedly, I have a personal angle on this, because I worked inside TransLink's planning department for two long stints, for a year in 2005-6 and for six months in 2011. (I have assisted them as a consultant since, but I have no contracts with TransLink now and no expectation of one.) It was, I thought, an unusually forward-thinking and principle-driven transit planning department. I assumed this was an expression of Metro Vancouver's unusual culture of intentional, strategic, controlled urban development. It also reflected an era of leadership that created the space for these thoughts to occur, as opposed to the crisis-by-crisis lifestyle that too often prevails in transit management.

The conversations that were happening at TransLink — especially about the difficult question of how a regional transit agency can form a reality-based relationship with its constituent cities — were extremely sophisticated and respectful. How should a large regional agency interact with city governments when it holds the technical expertise about transit that city governments mostly lack? For example, when a city government demands something that is geometrically impossible, how can the transit agency's response avoid appearing overbearing? Much of what I now know about this relationship, and the unavoidable forces operating on it, I figured out while helping with policy development there.

Today, those issues are at the core of my practice, as the relationship between city governments and transit authorities becomes an urgent issue almost everywhere.

Special-purpose regional governments are vulnerable creatures. The marquee leaders of an urban region — usually major mayors and state/province leaders — influence them but don't control them directly enough to feel responsible for them. Blame is easily shifted to them by the more powerful governments all around them.

All this is even more true when the product is transit, for four reasons.

First, transit somehow looks easy, in a way that water and power and regional land use planning do not. Many reporters have no factual frame for thinking about transit, and treat anyone with a simplistic answer as an expert. (Tip: my book can help provide that frame.)

Second, transit's success is utterly dependent on municipal actions around land use and street design, so regional transit agencies that are thinking strategically must form an interest in those municipal decisions. This is easily characterized as interference with municipal sovereignty. (I always advise transit agencies to respect local right to make decisions but to clearly describe the transit consequences of those decisions, in advance.)

Third, everyone is now screaming at transit agencies to innovate, and yet voters have zero tolerance for risk. Some of TransLink's failures are arguably innovations that didn't work out. If you expect everything your agency does to be successful, then quit telling them to innovate, because failure is intrinsic to innovation.

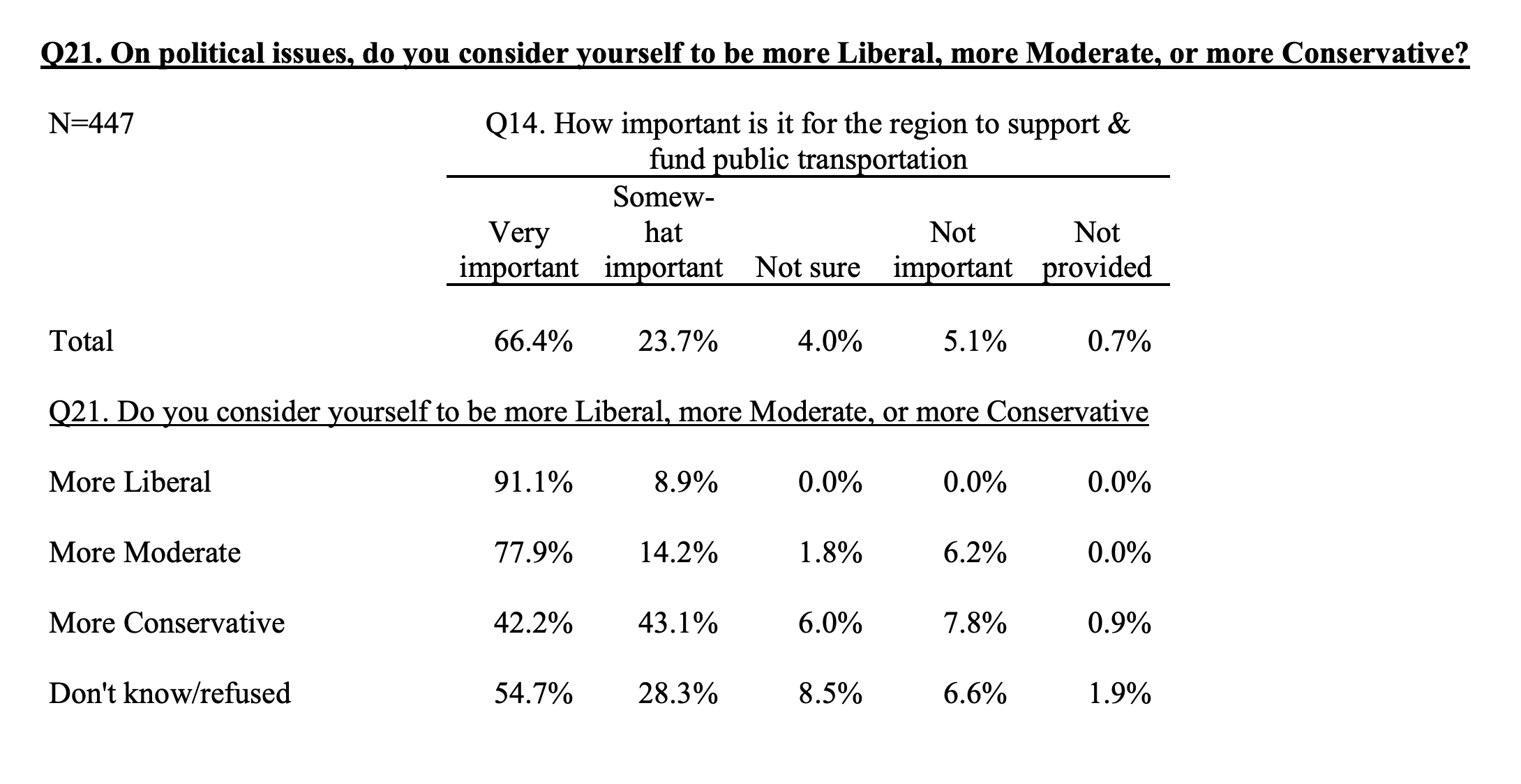

Fourth, transit, when considered in isolation as in Metro Vancouver's referendum, cannot avoid generating a ferocious difference in opinion across different parts of an urban region. In any region, maps of votes on transit referenda are mostly maps of residential density (Vancouver, Seattle), and for good reason. Transit demand rises exponentially with density: doubling density makes it more than twice as urgent. So of course the average core city dweller views transit as existential while the average outer-suburbanite on a cul-de-sac views it as unimportant. Giant regional transit agencies will continue to be pulled apart by these forces until we stop having regional transit debates and start having regional transportation debates. (The other important trend, in response to this basic math, is that core cities must exert more leadership, and funding, on their own transit issues. More on that below.)

What is amazing, then, is not that regional transit agencies are having political problems, but that so many of them are doing so well, considering. Many regions are moving forward with strong regional transit strategies, supported by working majorities of voters. Many are also making tough choices, like the painful shift in priorities that underlies Houston's new network.

Hating your transit agency is easy and fun. You don't have to understand your regional politics, in which the real power to fix transit is usually not held by the transit agency. You can also have the thrill of blowing up a big institutional edifice, as Metro Vancouver voters may now have done.

But a lot that's good will also be destroyed. In Metro Vancouver, amid all the recriminations, TransLink has lost the credibility it needs to lead reality-based conversations about transit. Maybe some other agency will step into that role. (Indeed, core cities for whom transit is an existential issue must develop that capability.) Or maybe there will just be many more years of blame shifting among the elected officials who really control transit in the region.

If you look at transit from the point of view of a state or province leader, you can understand why so many politicians are terrified of the issue. Everyone is screaming at them about it, pushing simplistic solutions, and the issue is polarizing on urban-suburban lines. Some huge problems, like equipment failures due to deferred maintenance, are curses laid upon us all by our parents' generation. What's more, most elite leaders are motorists, and need help finding their feet in the geometric facts of transit where a motorists' assumptions lead them astray. So they panic, shift blame, and leave transit agencies appearing to have more power to solve problems than they actually have. If you've never been a political leader, don't be sure you wouldn't do the same in their place.

Be patient. Breathe. Resist the desire to see your transit agency in smoldering ruins. Then, demand leadership. Demand state/provincial leadership that looks for solutions instead of pointlessly stoking urban-suburban conflict. (One possible solution is to spend more time on regional transportation debates instead of just transit debates, because regional transportation plans can look more balanced than transit plans can.) And yes, if your transit agency is being given dysfunctional direction by the region's leaders, demand a better system with more accountability to an elected official who will have to answer for outcomes.

Finally, if you live in a major city that cares about transit, demand that your city leaders look beyond blaming the transit agency, and that they do everything they can themselves to make their transit better. Remember, your city government, through its powers of land use planning and street design, controls transit at least as much as the transit agency does. Ask them: What is their transit plan? Tell them to follow the work of cities that are investing in transit themselves, beyond what their transit agency can afford, like Seattle and Washington DC., or for that matter transit-ambitious secondary cities like Bellevue, Washington, who have their own transit plans to guide the city's work. No regional or state transit authority — beholden to state or regionwide government that is dominated by less urban interests — is going to meet all of the transit needs of a dense, core city that has chosen to make transit a foundation of its livability. Their staff may well be doing what they can with the direction that they have, but they need your city government's active support, involvement, leadership, and investment.

Sorry, transit is complicated. It's fun to blow things up, as Metro Vancouver's voters probably have. But the solutions are out there, if we all demand leadership, and offer it.