Last Thursday, I joined a panel discussion put on by the Seattle Times about "gridlock". Mike Lindblom of the times summed it up here, and I previewed it here, but I'm thinking about the guy who came up to me afterward.

At great length, he told me that Seattle's streets had been planned and designed for cars. He began listing specific streets, why they were built as they were, with the number of car lanes that their designers had intended.

He objected to what was happening to his city's streets: replacing 4 tight lanes with 2-3 lanes to add room for bikes, pedestrians, and transit stops. Not because he hates those things, but because we were betraying the original intent of the design. These were meant to be car streets, so they should always be car streets.

The conversation sticks with me because he wasn't angry. (Angry people are boring and unmemorable.) Instead, he seemed more offended and hurt. The urbanists remodeling Seattle's streets were betraying a promise that someone had made to him.

I don't agree, but I can feel his feeling. This kind of empathy, I contend, is a stance worth practicing.

Here's an example, or maybe a confession. I'm one of those tech users who've been trained by experience to fear so-called upgrades. Just now, Apple told me to upgrade to "El Capitan," and all about how it would be better. None of the featured improvements are things I want, so my first reaction is that they're just adding complexity and thus increasing the risk of malfunction and confusion. Based on my experience, I'm entitled to suspect that (a) they've probably introduced new bugs and (b) they've probably wrecked something that I do value about the current version.

So I'm kind of person who upgrades at the last possible moment, only when the oldest version is collapsing into engineered rubble.

Computers are one of many spheres where I'm happy with what I have and would prefer it quit changing. What's more, what I have and like is what I feel the tech companies promised me, in other marketing messages long ago, a promise that I can now see them as betraying.

Maybe you don't have this feeling about computers, but I bet you have it about something.

Another word for this feeling of betrayal might be invasion. Because really, we're talking about home, and the fear of the invasion of home.

In my early fifties, I'm at home with with my hard disk and thumb drives, just as my mother, in her seventies, is at home with notebooks and manila file folders. When Millennials tell me my stuff should be in the Cloud, it doesn't matter what the argument is. The feeling is that Stalin plans to knock down my sturdy and ancient hovel, move me to a shoebox in a concrete modernist tower, and put all my stuff in some mysterious storage promising me that the System will take care of it.

So yes, I'm conservative in this most primal sense of the word: I get defensive about various kinds of home: physical and intellectual. And at this primal level, I bet you are too. You may be sold on the Cloud — and maybe you're right — but I bet you have a ferociously defended sense of home about something. If you feel aversion about something changing, or anger about something having changed, that's it.

And this kind of conservatism could be more compatible with advocating necessary change, but only if we who advocate change could hear it, and convey that we hear it.

Now and then I'm reminded that for a lot of people, "home" includes their car. If that's the case, then of course "traffic" is as offensive as Stalin threatening to knock down your hovel. And then I see this on a street in Portland today:

This is the universal fear-image of other people's cars: not your friends and family, and therefore something invading your neighborhood, your home. (It's a night image because in the day you might recognize the driver, and be less fearful.) And so the battle between homes, yours and that evil motorist's, is joined.

I think about these things on a rainy weekend to remind myself that conflict about changing the built environment is inevitable, because we are so deeply wired to fear for our homes. What's more, our sense of home can be so extended into the world (as our cars, neighborhoods, or for environmentalists, our planet) that it will inevitably conflict with the "home" of others..

But even if we can't agree with someone about an issue, we should practice empathizing with the feeling that something we rely on is under threat. Because on some issue, I bet you have that feeling too.

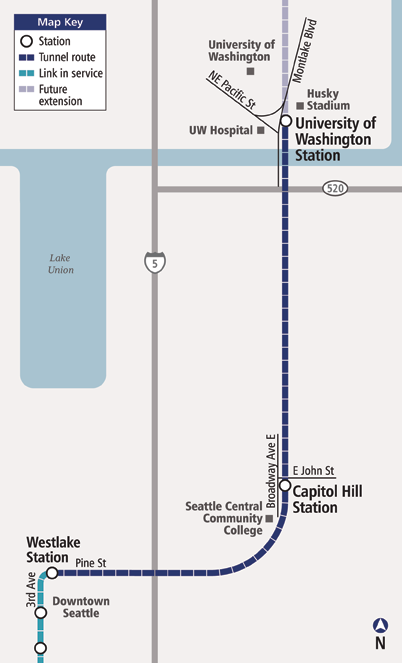

he dense Capitol Hill neighborhood, opens today. And if you vaguely associate Seattle with vast

he dense Capitol Hill neighborhood, opens today. And if you vaguely associate Seattle with vast