Very bad transit service cuts are coming to Portland.

Just a couple of years ago, we worked with Portland’s TriMet to develop an ambitious service expansion plan called Forward Together. Now, the agency is saying instead that they are facing a dire financial shortfall and need to make service cuts. I’m not sure why this message has changed so suddenly, apart from the failure of the state legislature to provide a new funding source for operations. In any case, the agency’s current position is that they have to cut service now to avoid worse cuts later, although worse cuts may be coming later anyway.

You can peruse the cuts here. If you live in the region, you should comment before Saturday, January 31.

I have several thoughts, which are further below, but it’s best to start by looking closely at the single most shocking cut they propose.

Abandoning a Major Hospital?

This may well be the first time that a US transit agency has proposed to abandon all service to a major medical center: Providence in inner northeast Portland. It happens to be a landscape I know well. I live nearby, grew up even closer, and go to the Providence complex for most of my healthcare. Also, I first moved to Portland in 1969 (I was 7, but already a transit geek) so I know some useful history.

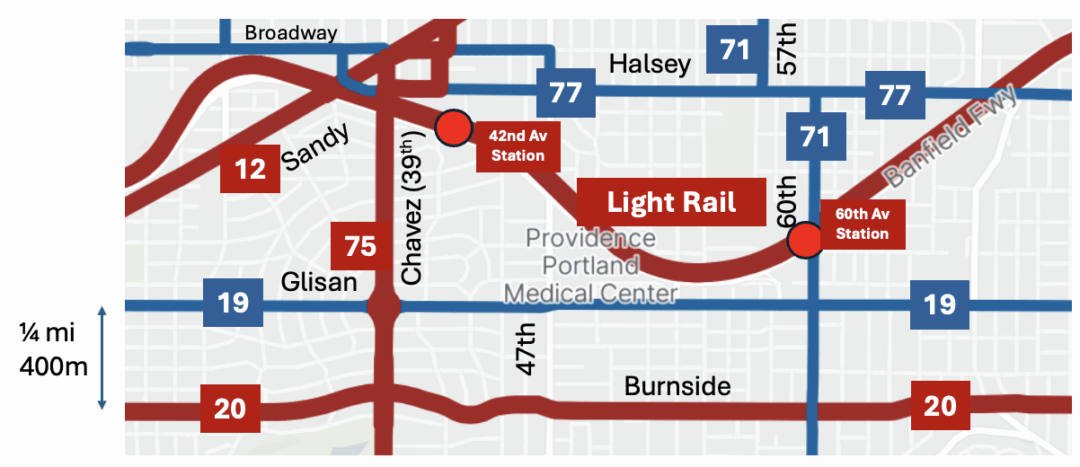

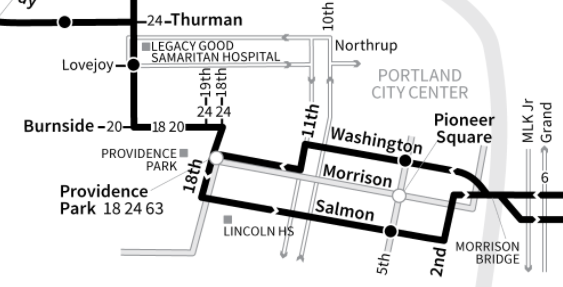

This part of northeast Portland is a fairly dense area with a good street grid where a lot of housing is being added along frequent transit corridors (red in my sketch, which is based on a Remix plot):

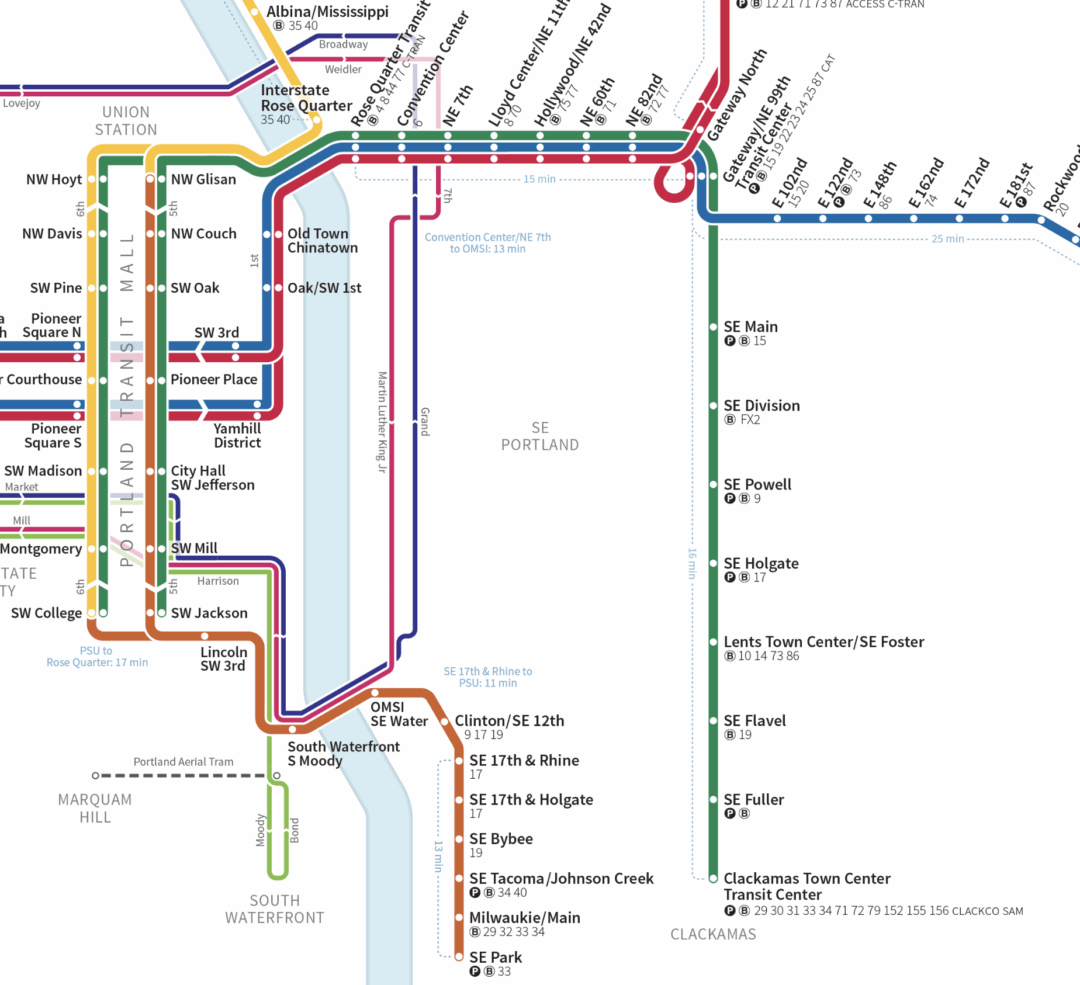

In this inner-city context, most of the blue lines, which currently run every 20-30 minutes, should be every 15 minutes, because they can perform well as part of a frequent grid. But in fact only the red lines are frequent. There’s also the sinuous light rail line, following I-84, but it only has two stations in this area, at 42nd and 60th. Do not ask me why there is no station at Providence, whose campus lies between 47th and 52nd right next to the rail line.

Now, TriMet proposes to entirely delete Line 19 on Glisan. This would remove all service within 1/4 mile walk of the Providence complex.

I was an intern at TriMet around the time of the 1982 redesign that created the current grid. At the time, all the lines on this map were made frequent (every 15 minutes or better) except for Glisan. The network is designed mostly around the principle of 1/2 mile spacing between lines, because many people will walk up to 1/4 mile to useful service. Glisan is only 1/4 mi from Burnside, too close for both to be frequent (at least in the context of the scarcity of service that is typical in the US).

Glisan is a mixed bag as a transit street. West of Providence, the neighborhood of curving streets is Laurelhurst, an area of low density and hence low demand. But Providence itself is a massive complex, a major hospital and a large building of medical clinics where many people come for appointments. Further east, beyond 60th, Glisan is a better transit street than Burnside for a while: it has a grocery store and apartments in this segment, while Burnside is climbing over the north shoulder of Mount Tabor, which limits development potential there. But long ago the decision was made that Burnside, not Glisan, would be the Frequent Service street, where TriMet would protect 15 minute frequencies at most times of day.

Now, if TriMet has to remove the 19, all the options are truly hideous. Abandon Providence entirely, along with the moderate income area and moderately dense area along Glisan east of 60th? Deviate the Halsey line (77) down to Glisan, just between 47th and 60th, to touch Providence, making it longer and thus less useful for through travel? Deviate the Burnside line up to Glisan, violating the principle that Frequent Service lines should aim for permanence since they’ve been used as the basis of dense housing development (including some on the segment that we would miss if we deviated in this area)?

I don’t know what TriMet will do. I don’t know what I’d recommend, except to say that a city with Portland’s pretensions to sustainability should not be in this position.

The Overall Design of the Proposed Cuts

The fact that service is being cut is a financial decision out of the control of TriMet’s service planners. Given the direction to make harmful cuts, I think they’ve done a good job in minimizing the harm. Some things I especially respect are:

- Sharing the pain with the light rail network. Until 10-20 years ago, many agencies would have started this process from the assumption that the rail service is special and must be protected, leading to even more destructive cuts to bus service. Instead, TriMet proposes to cut back the Green Line to just its unique segment south of Gateway, where it would operate as a feeder to the Red and Blue lines. This is a frequency gut cut all along the east-west segment now served by Red, Blue and Green (from 5 min to 7.5 min) but it’s also a cut to north-south frequency along the transit mall in the heart of downtown, from 7.5 to 15 min. A 15 minute frequency is really not relevant to internal circulation in a downtown, serving trips of under 2 miles, and the whole design of the transit mall (as redone in 2008) presumes that rail, not buses, serves this circulator function. Now that won’t work at all. So yes, a terrible cut at the heart of the system. But light rail operating costs are high, and if they didn’t cut light rail they’d have to utterly devastate the bus network.

- Some service designs that are improvements. Our Forward Together project included many ideas that have been carried forward here, though without enough frequency. (Continuous service the whole length of Woodstock Blvd, for example.)

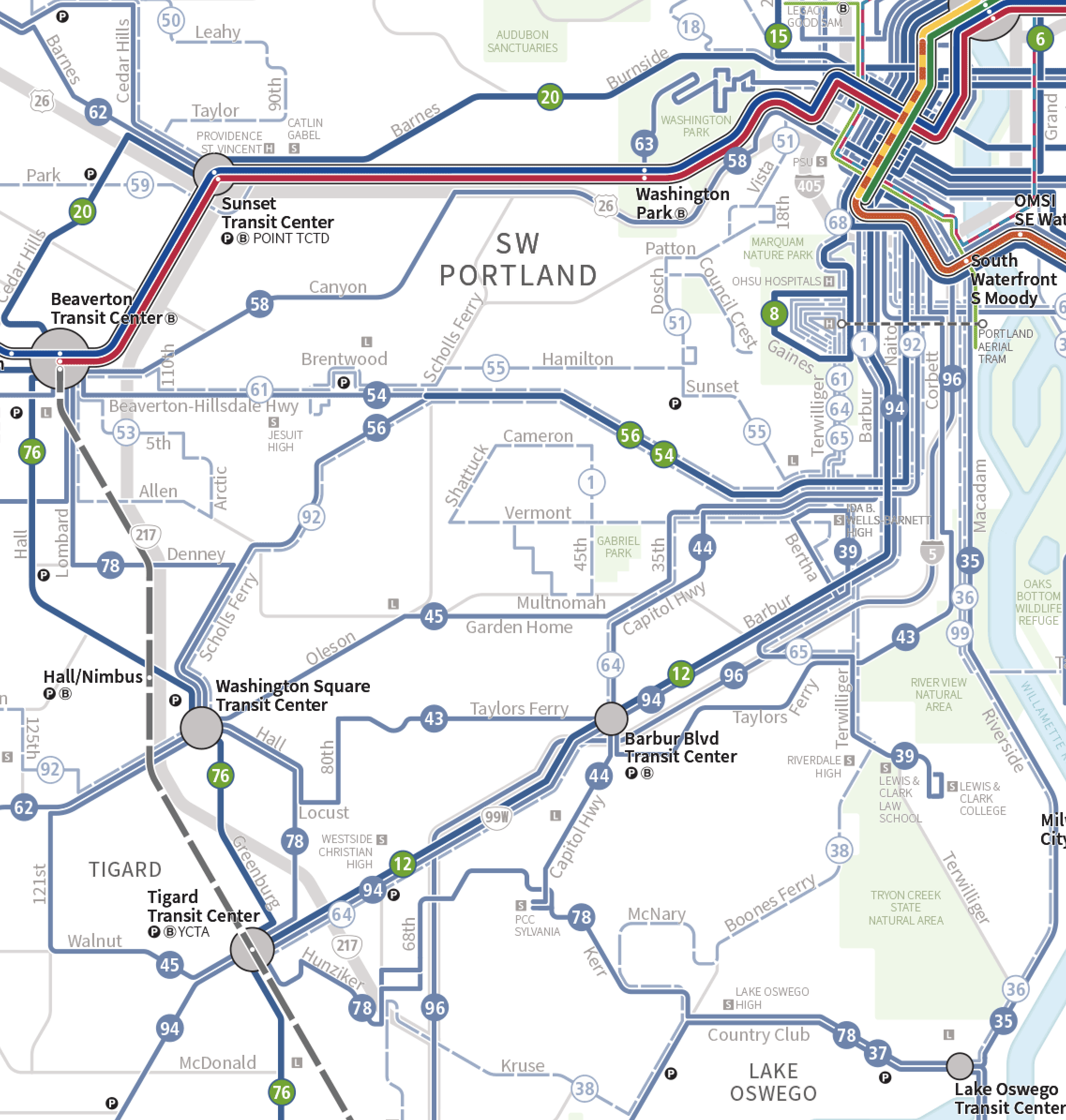

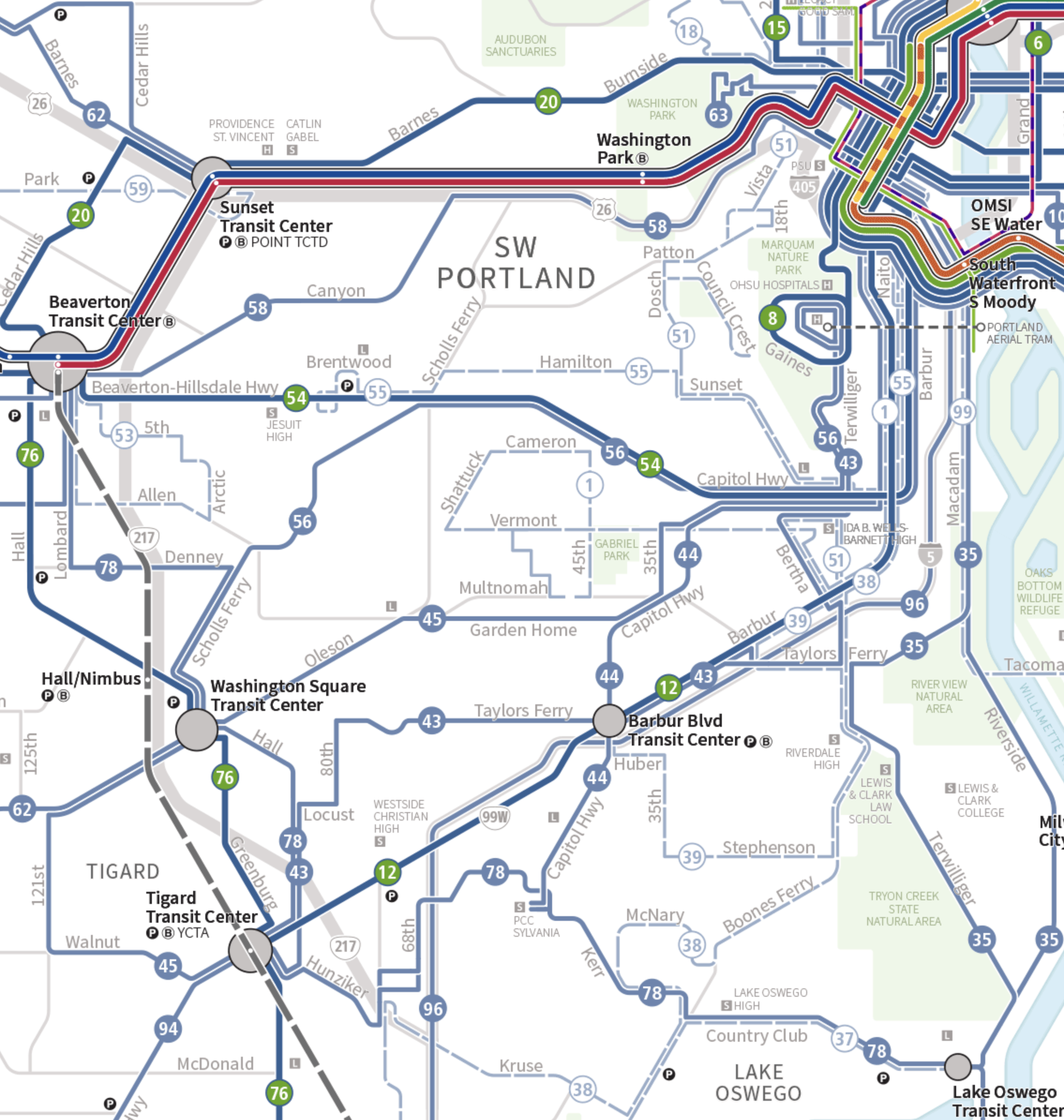

- Balanced removals of coverage. The principle of the Forward Together project, as endorsed by the agency’s Board, was that service needed to be justified by either ridership or equity. That means that low-ridership service can be offered only where it responds to a demonstrated social or economic need. As part of the Forward Together plan, TriMet has already deleted low-ridership “coverage” services in relatively affluent parts of the region, and they continue to do so in this proposal.

But overall, the plan’s impacts are dire.

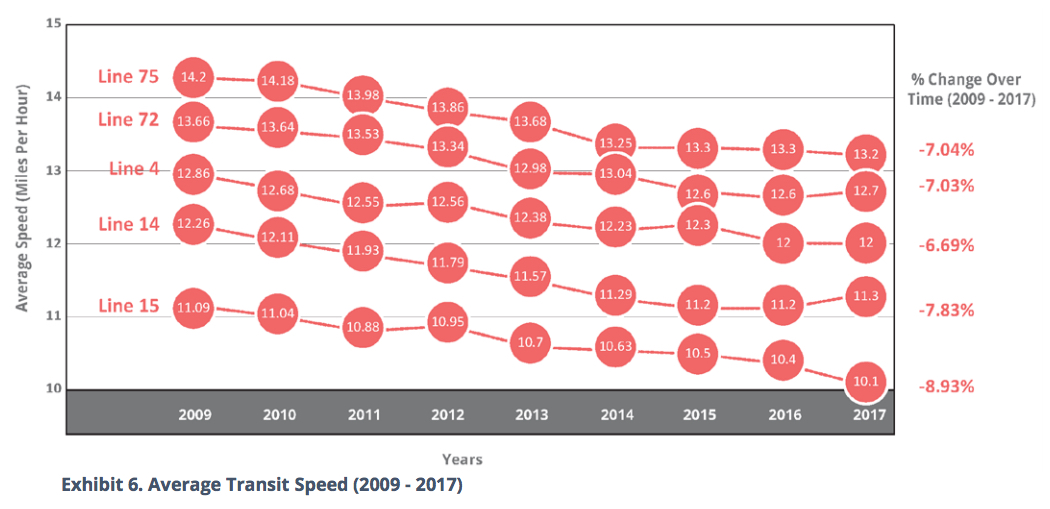

What’s more, there’s a serious risk that in the public outreach process happening now, more people will defend the deleted routes than defend the Frequent Service network. This could pressure TriMet to cut frequencies on this backbone of the region. We have already done this experiment: In the 2009 financial crisis TriMet cut Frequent Network frequencies from 15 minutes to 16-17 and triggered a dramatic loss of ridership. Frequency is never visible enough on the map, which makes it hard to defend when people are complaining about losing all of their service, yet frequency is the key to ridership. This is the eternal ridership-coverage tradeoff.)

Do We Really Want to Do This?

Oregon’s legislature recently went through a spectacular failed effort to pass a statewide transportation funding measure, where rural legislators demanded maintenance for their roads but were eager to strip out transit operating funds for cities. A measure passed that funds transit only through 2028, but that has been referred to the voters, with an election scheduled for May.

It seems likely that the best we can hope for from the state is a short-term rescue. Leaders in the region — probably working through Metro or the City of Portland — are going to have to step up if they want to save what was once one of America’s most admirable transit agencies.