For the past few years, planners at the transit agency TriMet and MPO Metro in Portland have been carefully shepherding the development of a new sort of transit project for the city. It’s turning into a new sort of transit project, period — one that doesn’t fit in the usual categories and that we will need a new word for.

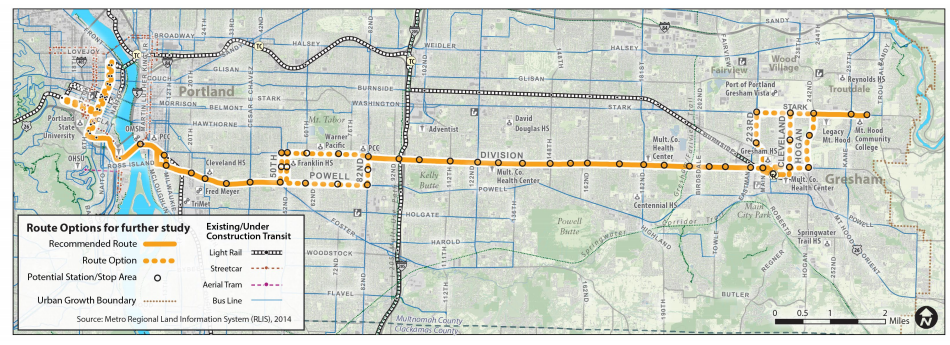

The Powell-Division Transit and Development Project extends from downtown across Portland’s dense inner east side and then onward into “inner ring suburb” fabric of East Portland — now generally the lowest-income part of the region– ending at the edge city of Gresham. It was initially conceived as a Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) line, though one without much exclusive lane. It would be a new east-west rapid element in Portland’s high-frequency grid, and also serves a community college and several commercial districts.

(Full disclosure: JWA assisted with a single workshop on this project back in 2015, but we haven’t been involved in over a year.).

Below is a map of how the project had evolved by 2015, with several routing choices still undetermined. From downtown it was to cross the new Tilikum bridge and follow Powell Blvd. for a while Ironically, as inner eastside Portland began to be rethought for pedestrians and bicycles, decades ago, Powell was always the street that would “still be for cars.” To find most of the area’s gas stations and drive-through fast food, head for Powell. As a result, it’s the fastest and widest of the streets remaining, but correspondingly the least pleasant for pedestrians.

Half a mile north is Division Street. For the first few miles out of downtown, Division is a two lane mainstreet, and it’s exploded with development. It’s on the way to being built almost continuously at three stories. Further out, Division is one of the busier commercial streets of disadvantaged East Portland, though still very suburban in style as everything out there is. (For an amusing mayoral comment on that segment, see here.)

Because dense, road-dieted Division is very slow close to the city but wide and busy further out, the project began out with the idea of using Powell close-in and then transitioning to Division further out, as Division got wider, though of course this missed the densest part of Division, which is closest-in.

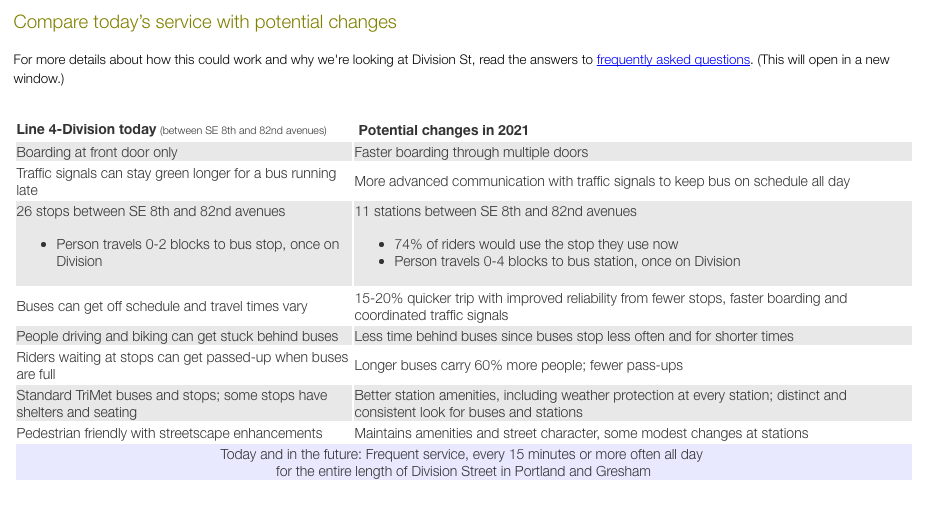

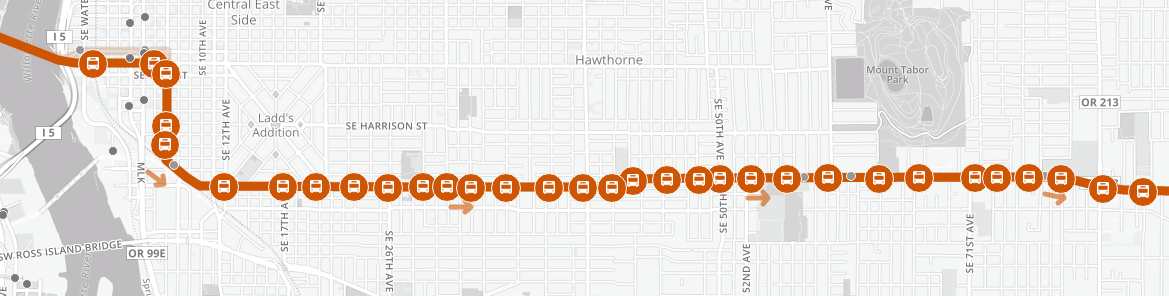

However, very little of the corridor would be separated from traffic. While this project was never conceived as rail-replicating, it was based on the premise that a limited-stop service using higher-capacity vehicles, aided by careful signal and queue jump interventions, could effect a meaningful travel time savings along the corridor, compared to trips made today on TriMet’s frequent 4-Division. That line runs the entire length of Division and is one of the agency’s most productive lines, but it struggles with speed and reliability.

As it turned out, though, the travel time analyses showed that from outer Division to downtown, the circuitous routing via Powell cancelled out any travel time savings from faster operations or more widely spaced stops.

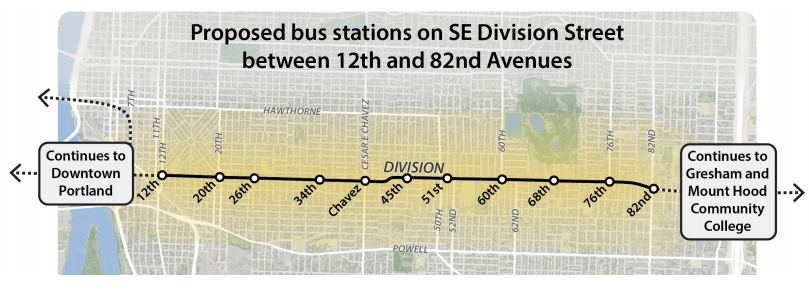

As a result, planners looked at a new approach, one that would seek to improve travel times by using inner Division, which had previously been ruled out. Inner Division is a tightly constrained, 2-lane roadway through one of the most spectacularly densifying corridors in Portland, and one that is rapidly becoming a prime regional dining and entertainment destination. This development has led to predictable local handwringing about parking and travel options. Here’s what that alternative looks like:

Proposed Division station locations

Current 4-Division eastbound stops

The new plan is basically just stop consolidation with some aesthetic and fare collection/boarding improvements. But the stop consolidation would be dramatic. Note that one numbered avenue in Portland represents about 300 feet of distance, so the new spacing opens up gaps of up to 2400 feet. If you’re at 30th, for example, you’d be almost 1/4 mile from the nearest stop.

Such a plan would be controversial but quite also historic. It’s a very wide spacing for the sole service on a street. On the other hand, the wide spacing occurs on a street that is very, very walkable — one of the city’s most successful “mainstreets” in fact. And it’s basically the only way to optimize both speed and frequency on a two-lane mainstreet like inner Division.

At this point, it would be strange to call this project “BRT” (Bus Rapid Transit); even the project webpage refers to this alternative as “Division rapid bus”.

Disappointing as this will be to those who think BRT should emulate rail, it has one huge advantage over light rail. In Portland, surface light rail tends to get built where there’s room instead of where existing neighborhoods are, so it routinely ends up in ravines next to freeways, a long walk from anything. This Division project now looks like the answer to a more interesting question: What is the fastest, most reliable, most attractive service that can penetrate our densest neighborhoods, bringing great transit to the heart of where it’s most needed?

This is such a good question that we shouldn’t let arguments about the definition of “BRT” distract from it. Because it’s not a question about technology. It’s a question about people.

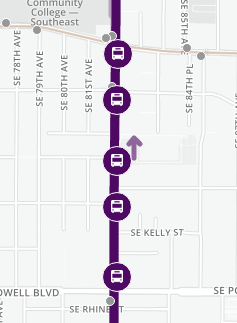

Line 72 stopping pattern (Powell to Division, approx. 0.5 mi)

Upgrading the 4-Division to a rapid bus line (without underlying local service, which is impossible due to the constrained roadway) should present a real improvement in quality of service (in terms of capacity using the larger vehicles, and in a 20-25% travel time savings), while at the same time being easier to implement and less disruptive to existing travel patterns.

It also provides a template for TriMet to consider stop consolidation and frequent rapid service on other corridors like the aforementioned Line 72. Rather than seeing this as a failure to design a rapid transit project, perhaps we can celebrate a process that has steered away from a path that would have resulted in a disappointing outcome, towards a more limited, more economical, but still meaningful improvement for riders.