Short answer: Because the buses are timed to meet each other, and this is harder than it looks.

Long answer: If you’ve used public transit in an area that has infrequent trains, including the suburbs of many cities, you’ve probably wondered why the bus and train schedules aren’t coordinated. Why didn’t they write the bus schedule so that the bus would meet the train?

First of all, let’s gently note the bias in the question. Why didn’t you ask why the train wasn’t scheduled to meet the bus? We assume that because trains are bigger, faster, and more rigid, they are superior and buses are subordinate. You’ll even hear some bus routes described as “feeders”, implying that they have no purpose but to bring customers to the dominant mode.

But it’s rare for an efficient bus route to have no other purpose than feeding the train. Public transit thrives on the diversity of purposes that the same vehicle trip can serve. At a busy rush hour time, you may encounter a true feeder bus that’s timed to the train and will even wait if the train is late. But most bus services carry many people locally in their area, on trips that don’t involve the train connection. For these networks to work, they have to connect well with themselves, and this is harder than it looks.

We’re talking here about infrequent bus routes (generally every 30 minutes or worse) and infrequent trains. When frequency is high, no special effort is needed to make the connection work.

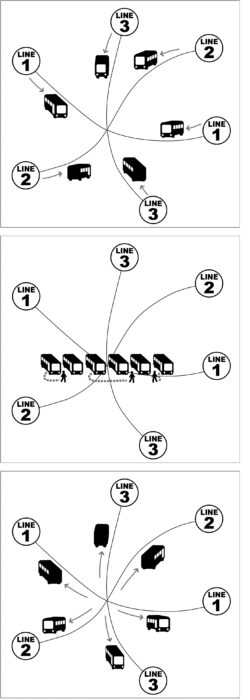

Pulse scheduling. Buses of many lines are coordinated so that buses meet at the same time each hour, allowing fast transfers despite low frequency.

Infrequent transit networks have a huge problem. There’s not just a long wait for the initial bus or train. There’s also a long wait for any connection you may need to make to reach your destination. We often combat this problem with pulse scheduling. At key hubs, we schedule the buses to all meet at the same time each hour or half hour, so that people can make connections quickly even though frequencies are low. We design the whole network around those connections, because they are so important to making the network useful.

That means that the whole schedule has to have a regular repeating pattern. As much as possible we want this pattern to repeat every hour, so that it’s easy to remember. We even design route lengths to cycle well in this amount of time, or multiples of it.

If the train schedule has a similar pattern, we will certainly look at it and try to match our pattern to it. But the timing of a pulse determines the schedules of all the routes serving that point. Sometimes we have lattices of interacting pulses at several points, which can make an entire network interdependent. You can’t change any of these schedules without changing all of them, or you lose the fast connections between infrequent bus routes that makes suburban networks usable.

Sometimes, an infrequent trunk train service will also present a repeating hourly cycle in its schedule, and if so, we’ll look at that and try to coordinate with it. But at most this will be possible at a couple of stations where the timing works well, because of the way the local bus schedules are all connected.

More commonly, especially in North America, we face an irregular regional rail or “commuter rail” schedule, where there may be a regular midday pattern but there’s often no pattern at other times. The pattern may often shift during the day for various reasons that make sense for the train operation. All this is toxic to timing with the local bus network. Local bus networks need that repeating hourly pattern to be efficient and legible. For example, if at 1 PM the train pattern suddenly moves five minutes earlier, the bus network can’t adapt to that without opening up a gap in its schedules that will affect lots of other people.

Usually, the regional rail network and the local bus network are part of different transit authorities, which makes this an even bigger challenge. A particular problem in multi-authority region is that different authorities may have different schedule change dates, sometimes baked into their labor agreements, and this prevents them from all changing together at the same time. But the core problem isn’t just institutional. Merging the authorities won’t solve it. No efficient bus system – working with sparse resources and therefore offering infrequent service – can make timed connections with a train schedule at every station, and especially not if the train schedule is irregular. It’s just not mathematically possible.

The best possible outcomes happen when the rail and bus authorities have a relationship that recognizes their interdependence rather than one based on a supposed hierarchy. That means that the rail authority recognizes that the local bus authorities can only connect with a repeating hourly schedule pattern, and tries to provide one. It also means that rail schedule changes are made with plenty of warning so that there’s time for bus authorities to adapt.

With the decline of rush-hour commuting due to increased working from home, transit demand is even more all-directions and all-the-time. It no longer makes sense to just assume that one trip – say, the commute to the big city – is superior to another, like the local trip to a grocery store or retail job. All possible trips matter, and we get the best transit network when authorities coordinate to provide the best possible connections for all of them.

The same logic applies to infrequent ferry services.

Yes, of course.

The best possible outcome is a Verkehrsverbund, where the authority over service levels (meaning schedules and fares) is with the “umbrella” agency, and where the operators have simple operation contracts with specified service levels.

This also solves the timetable changing issues.

“We’re talking here about infrequent bus routes (generally every 30 minutes or worse) and infrequent trains. When frequency is high, no special effort is needed to make the connection work”.

In much of Europe, passengers would never accept that everything more frequent than 30 minutes is “frequent” and doesn’t require coordinated timetables. Here in Stockholm we have buses that are timed to meet the metro, even when the metro comes every 10 minutes. Generally, rail-bus connections (not bus-bus connections) have the highest priority, since that is how most passengers travel.

Also check the timetables for Frölunda Torg in Gothenburg. They have pulse connections every 10 minutes during most of the day.

Still I feel that we are inferior to the Verkehrsverbund countries, with their integrated planning with coordinated timetables across the whole network.

I am guessing this post is related to the Suffolk County post, as the Long Island Rail Road is a major factor there. There does seem to be some hourly consistency in LIRR schedules during midday and weekends. Perhaps timing buses to meet trains at those time periods would be possible.

However, the biggest problem would be when the same bus route serves two or more rail stations or timed transfer points. It really may not be possible to coordinate all those buses with the rail system.

It seems to me the next best solution would be to make any necessary wait as comfortable as possible with amenities, such as benches, shelters (even better if climate controlled), stuff to read, and possiblity to buy snacks/drinks. I’m not very familiar with the East Coast, so may some of that already exists.

The amenities idea makes sense for long-distance transportation (e.g. airports). But, it is not appropriate for people’s everyday commute trips. For an everyday trip, that doesn’t work. Nobody is going to choose a two-hour transit trip over a 30-minute drive, no matter what amenities you provide for the 55 of those 120 minutes spent sitting around at a train station waiting for a bus.

This makes sense in theory, but I have seen enough empty buses leave the rail station i use (which is also a bus hub, for different agencies, and is located in an urban area) as i come down the stairs — instead of waiting for a few minutes — to switch modes for my last miles. it’s especially galling as the bus schedule is a vague idea rather than a dependable occurrence: the next bus may come in 10 minutes or 30 minutes, and there’s no way to tell which. At the tail end of a 2 hour commute that makes a big difference to me.

My system has one of our two pulse points at an hub what is also served by 10 Amtrak trains a day (5 in each direction). We get asked this question all the time, and your answer is on point. However, there is one more variable:

The Amtrak train’s schedule is very unpredictable. Rarely they are right on time. Sometimes they are 25 minutes or more late, and anywhere in between. There’s also no real way to know when you’re waiting there. Even if it was relatively simple for the bus schedule to align (it isn’t, the trains don’t follow any sort of clockface schedule even on paper), they don’t follow the printed schedule with any kind of regularity so the point is moot.

My apologies for my grammar in the first sentence. Moving too fast and didn’t proofread!

There are issues with reliability as well. Buses, trains (or ferries) can be late. Then there is the transfer time. Or more specifically, the range in transfer time. The stations themselves make a big difference.

For example, Sound Transit now runs the 522 bus to the Roosevelt Station (in Seattle). It was originally timed with the train. Part of the problem is that it is a deep-bore station. The bus doesn’t stop right by the station, either. So riders have to get off the train, take escalators (or elevators) up until they are at the surface, then exit the station and get to the stop itself. Some people do this quickly — others don’t. So even if the train is waiting there, and the train is perfectly timed, it isn’t clear how long it should wait. Average walk time? Worse walk time? What if worse walk time is longer than the frequency of the trains?

You have the same issues going the other direction, but you also have the reliability of the bus as well. If a bus gets there a couple minutes early, that is fine. But if the bus is a couple minutes late, you’ve blown it. It gets worse with the train (as Jack pointed out).

That is why they gave up on that idea. The bus just runs every so often (as does the train). The key (as it is with most transfers) is for them to be running frequently.

This also explains why it is rare to try and time connections when you run (relatively) frequently. A bus leaving a ferry dock may sit there quite a while, as people slowly stream on. It may leave the dock well after it is supposed to (because the boat was late). But it still makes sense to run that way assuming the ferry is infrequent (half hour or worse) and that is where most of the riders are coming from. Going the other way, the bus has to be scheduled to arrive well before the boat is supposed to leave (in case the bus gets delayed).

In keeping with the idea that transit is for more than peak-hour suburb-to-downtown commuting, there is the issue of coordinating connections in multiple directions. If a bus has to arrive early enough to let it passengers board the train, but also wait for the train passengers to board the bus, it will be dwelling at the train station for a while, but perhaps less than the interval between bus trips. And there can be trains in at least two directions, so which one do you sync with? All the more reason for higher frequency.

Long waits at the station are not always a problem – the bus drivers need regular times to get off the bus use a restroom and stretch their legs. However if you arrive on one bus and transfer to a different it needs to be a short wait. Thus if the bus only meets the train/ferry it works great to plan a long wait there. However if people might always want to transfer to a different bus going a different direction then that time the driver used is stolen from the riders and you should instead fine a place for the drive to take a break where there will be nobody on board (that is the end of the route).

If there is a long distance between the train/ferry and the bus, then it is physically impossible to time these connections without being unfair to someone. Either you rob time from someone who is getting on the next bus, or you make someone transferring from the train wait a full cycle.

That sort of dwell is ideal for a bathroom break for the driver and maybe 5 minutes of “not sitting”.

Buses that aren’t timed to the trains is only a symptom of the bigger issue: Segregation. In a typical American transit system, buses and regional trains targets completely different customers. Buses are for lowly paid (mostly people of color) service workers, while regional trains is for highly paid (mostly white) who works 9 to 5 in downtown. They are expected to drive to the train, hence the huge parking lots at the stations. High fares and very few trains outside of peak hours and peak direction discourages other people from the trains.

In Europe, buses and trains are used by the same people, therefore it’s natural for them to have coordinated connections.

Johnny has accurately described pre pandemic markets. However, stats from several metros indicate fewer 9-5 drones but more service workers and others using transit evenings and weekends returning post pandemic. As an example of a parallel train to train connection issue, Caltrain now publishes a specific timetable indicating NB and SB connection times at Millbrae where BART terminates directly adjacent the San Francisco-San Jose (limited extensions to Gilroy). This is serious progress given that the transfer has been problematic for over a decade and a half.

As to the reliability issue, given that we now have real time arrivals available on line, dispatchers in the various agencies should be able to contact the train or bus to seek a delay in departure time to allow the feeder to arrive. Yes, this will need some interagency cooperation, but making the system work better for the pax is the presumptive raison d’etre .

The Verkehrsverbund concept in Switzerland, Austria, Germany, Holland works wonderfully. Buses are timed to trains, S-Bahns, U-Bahns, trams. You espouse the benefits of the network; those benefits extend beyond just buses and should include the rail network. The planning and schedule creation for the rail network need to be unified with rest of the transit network and need to operate on the same pulses.

Two practices in the English speaking world really retard the full benefits of the networks. One is the balkanization of transit agencies, where each transit agency is led by its own board, has its own policies, sometimes fare media, its own website and schedule formats, and does its planning and fare setting for its own needs, and barely considers the interests and benefits of other operators. It’s exactly this problem that a Verkehrsverbund can solve, since it gives fare setting and scheduling responsibilities to the Verkehrsverbund.

The other is the relative disregard for schedule adherence. The European countries as well as Japan place a high value on conforming to the schedule, and have the tools to support the operator keeping on schedule and track performance. In our systems it’s not unusual for buses to begin at the terminal 5 minutes later if the operator thinks they will make it up, and the next operator to begin on time and get ahead of schedule. To really make it work, you need realistic schedules as well as a culture of adherence to the schedule, even if that means starting on time and waiting at points on the route or driving a bit slower or longer dwells at stops when appropriate

Dear all,

A good disccussion to which not much can be added, but which shows that bus and train integration strongly depends on the environment and legal and financial frameworks. But central for me is the will of the client or the carrier to add value. Arguments you put forward Jarret were also used in the 80s in the Netherlands and Switzerland. In the end it could be (much) better. ( Bahn 2000 in CH goes from EC to Postauto) and rural areas in the Netherlands, where integration goes so far that train drivers can also be bus drivers simultaneously.

To give some background information I have some presentations from a UITP congress on Bus Train integration in Switzerland and the Netherlands I’ll mail them to the HT mail address.

I have a quibble that I didn’t notice being addressed in the previous comments – every time you say “hourly”.

Even the value of “repeating pattern” is largely from its predictability and not solely from its repetition, but a known pattern affects the math and “hourly” is a social construct.