Short answer: Because the buses are timed to meet each other, and this is harder than it looks.

Long answer: If you’ve used public transit in an area that has infrequent trains, including the suburbs of many cities, you’ve probably wondered why the bus and train schedules aren’t coordinated. Why didn’t they write the bus schedule so that the bus would meet the train?

First of all, let’s gently note the bias in the question. Why didn’t you ask why the train wasn’t scheduled to meet the bus? We assume that because trains are bigger, faster, and more rigid, they are superior and buses are subordinate. You’ll even hear some bus routes described as “feeders”, implying that they have no purpose but to bring customers to the dominant mode.

But it’s rare for an efficient bus route to have no other purpose than feeding the train. Public transit thrives on the diversity of purposes that the same vehicle trip can serve. At a busy rush hour time, you may encounter a true feeder bus that’s timed to the train and will even wait if the train is late. But most bus services carry many people locally in their area, on trips that don’t involve the train connection. For these networks to work, they have to connect well with themselves, and this is harder than it looks.

We’re talking here about infrequent bus routes (generally every 30 minutes or worse) and infrequent trains. When frequency is high, no special effort is needed to make the connection work.

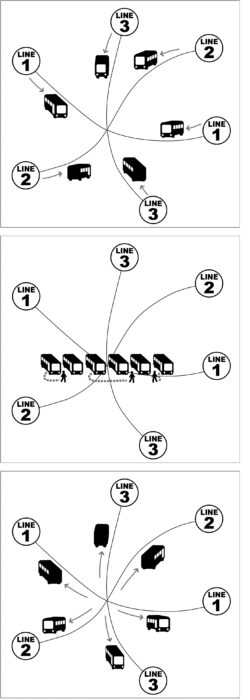

Pulse scheduling. Buses of many lines are coordinated so that buses meet at the same time each hour, allowing fast transfers despite low frequency.

Infrequent transit networks have a huge problem. There’s not just a long wait for the initial bus or train. There’s also a long wait for any connection you may need to make to reach your destination. We often combat this problem with pulse scheduling. At key hubs, we schedule the buses to all meet at the same time each hour or half hour, so that people can make connections quickly even though frequencies are low. We design the whole network around those connections, because they are so important to making the network useful.

That means that the whole schedule has to have a regular repeating pattern. As much as possible we want this pattern to repeat every hour, so that it’s easy to remember. We even design route lengths to cycle well in this amount of time, or multiples of it.

If the train schedule has a similar pattern, we will certainly look at it and try to match our pattern to it. But the timing of a pulse determines the schedules of all the routes serving that point. Sometimes we have lattices of interacting pulses at several points, which can make an entire network interdependent. You can’t change any of these schedules without changing all of them, or you lose the fast connections between infrequent bus routes that makes suburban networks usable.

Sometimes, an infrequent trunk train service will also present a repeating hourly cycle in its schedule, and if so, we’ll look at that and try to coordinate with it. But at most this will be possible at a couple of stations where the timing works well, because of the way the local bus schedules are all connected.

More commonly, especially in North America, we face an irregular regional rail or “commuter rail” schedule, where there may be a regular midday pattern but there’s often no pattern at other times. The pattern may often shift during the day for various reasons that make sense for the train operation. All this is toxic to timing with the local bus network. Local bus networks need that repeating hourly pattern to be efficient and legible. For example, if at 1 PM the train pattern suddenly moves five minutes earlier, the bus network can’t adapt to that without opening up a gap in its schedules that will affect lots of other people.

Usually, the regional rail network and the local bus network are part of different transit authorities, which makes this an even bigger challenge. A particular problem in multi-authority region is that different authorities may have different schedule change dates, sometimes baked into their labor agreements, and this prevents them from all changing together at the same time. But the core problem isn’t just institutional. Merging the authorities won’t solve it. No efficient bus system – working with sparse resources and therefore offering infrequent service – can make timed connections with a train schedule at every station, and especially not if the train schedule is irregular. It’s just not mathematically possible.

The best possible outcomes happen when the rail and bus authorities have a relationship that recognizes their interdependence rather than one based on a supposed hierarchy. That means that the rail authority recognizes that the local bus authorities can only connect with a repeating hourly schedule pattern, and tries to provide one. It also means that rail schedule changes are made with plenty of warning so that there’s time for bus authorities to adapt.

With the decline of rush-hour commuting due to increased working from home, transit demand is even more all-directions and all-the-time. It no longer makes sense to just assume that one trip – say, the commute to the big city – is superior to another, like the local trip to a grocery store or retail job. All possible trips matter, and we get the best transit network when authorities coordinate to provide the best possible connections for all of them.