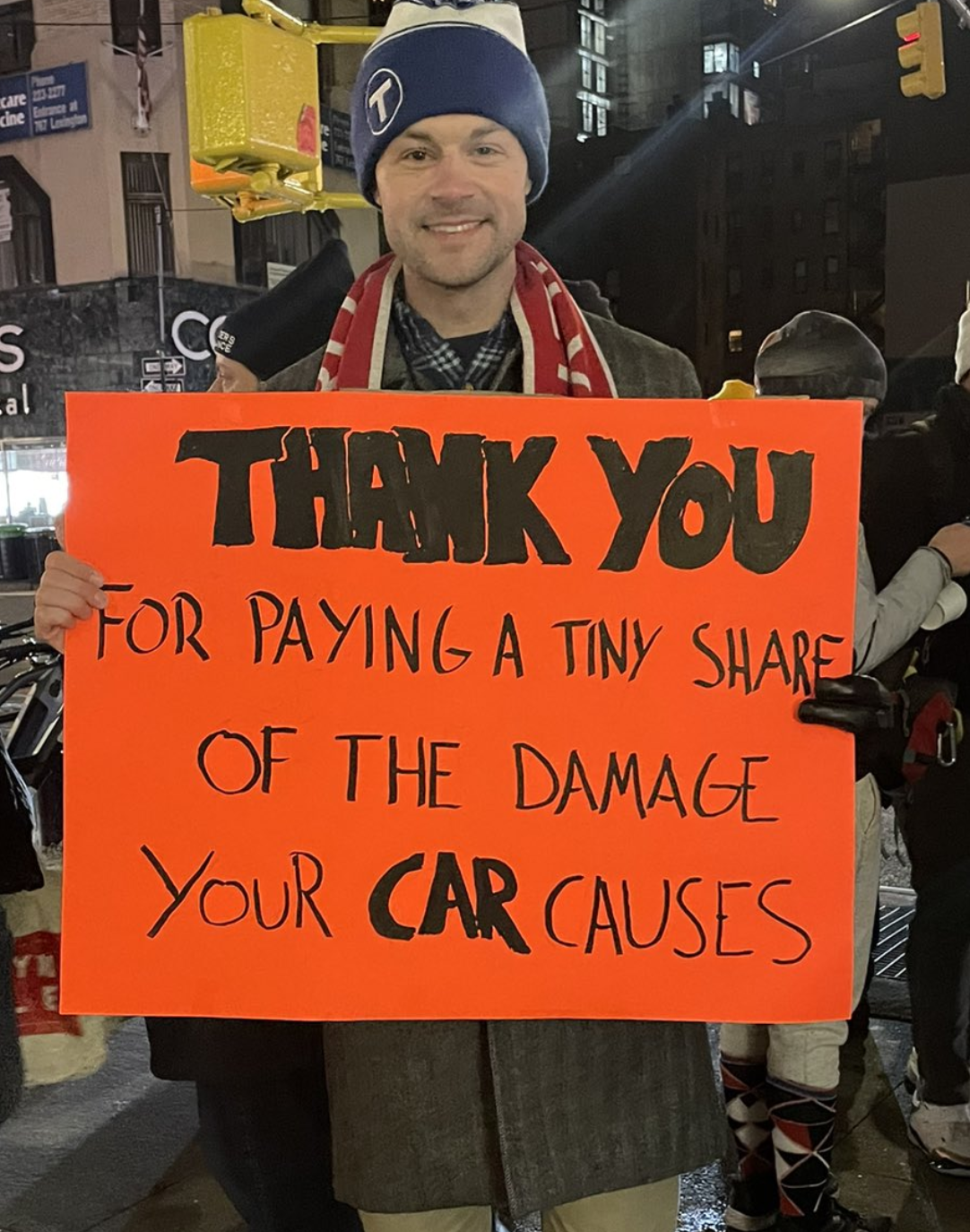

My friend and competitor James Llamas on the streets of Manhattan yesterday. He says he can’t take credit for the sign.

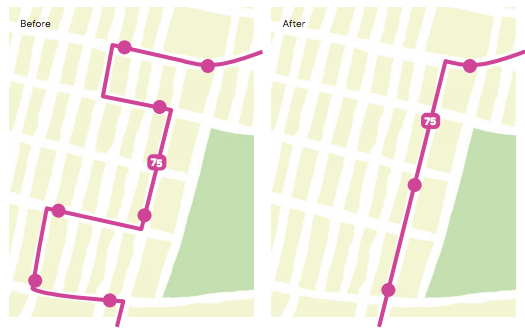

January 5, 2025 will be an important date in urban history. It’s the day that the idea of charging motorists to drive into a dense city center — already routine in Singapore, Stockholm, and London — first arrived in the Western Hemisphere. New York City’s Congestion Relief Zone, covering Manhattan south of 60th Street, will charge $9 for cars at most times of day. Trucks pay more based on weight, and the charge for all vehicles is reduced by 75% overnight.

For the first time in a Western Hemisphere city, there is a fair price to pay for taking up wildly valuable land in the urban core for the movement of your private vehicle. To put it another way, there’s a fair discount for all of the people who move around the city, contributing just as much to its life and economy, without taking all that space. The money collected will go largely to supporting desperately needed improvements to the transit network, so that more people will find it useful and even fewer will feel the need to drive.

(No, I’m not going to call it congestion pricing. That term was coined by economists and, like many academic terms, it’s useful in technical discourse but misleading on the street. It reminds me of other brands coined by opponents, like death taxes. You’ve combined two ideas people hate, congestion and pricing, and then you wonder why people don’t like it. I’ve advocated for decongestion pricing, because that says what the price buys, but I’m certainly fine with the emerging term Congestion Relief Zone. The problem is that opponents are always trying to imply that you’re just taking money without producing a benefit, so the benefit has to be right there in the name.)

What’s the point of road prices? The purpose is to expand freedom in the city by enabling more people to reach more destinations in less time so that they can have better lives, all without getting in each other’s way. As everyone who has studied this knows, and almost nobody else does, nothing works as well as prices to nudge some people make choices that reduce the harms they inadvertently do to others. And when you seize a big chunk of real estate in a dense city for your moving car, you are taking that space from other people. In congestion, your car obstructs the movement of other people who have as much right as you to be there. The Congestion Relief Zone will also increase overall freedom because more people will be able to access opportunity by all modes of transport, including by car.

The fight to make this happen has been epic. The way this issue polarizes urban vs suburban voters is terrifying to elected officials. New York Governor Kathy Hochul postponed the plan just as it was about to take effect in July 2024, and revived it, with a lower toll that will achieve lower benefits, only after the 2024 general election was past. Like all big steps, the consensus for the plan was cobbled together out of people who care about different things, under the overwhelming force of looming financial disaster for public transit in the US’s biggest and densest city. The plan finally happened partly because nobody could come up with a better way to fund the necessary repairs and modernizations in a transit network that everybody recognized as essential to the region’s economic life.

Many people are still furious, and while there are legitimate concerns (and have been many compromises already to address them) much of the whining now is largely self-incriminating. The region seems to contain a large number of people who can perfectly well afford $9 but would rather spend unlimited sums to trumpet their righteous entitlement to consume expensive real estate for free. There are of course tradespeople who need to get around in vans or trucks and will need to pass on the cost to their customers, as they should. A journalist found a real estate mogul who wanted to pose as a man-on-the-street at 61st & 3rd Avenue His complaint was that the one way street system requires him to enter the zone even though he lives outside of it, and that the $9 charge will prevent him from visiting his family 18 blocks away. Local impacts around a zone boundary are a legitimate issue, but in his case the replies are understandably not sympathetic.

I did just enough tweeting about this over the next two days to feel some of the wrath …

… and I understand it. This moment puts experts like me in the worst situation, saying: “We know this sounds awful, but trust us, it won’t be that bad.” But they don’t trust us, so we just have to breathe, accept their rage for a while, and wait for the evidence. People will adapt as they always have, in order to make things better than they expected. The first Monday morning is pretty encouraging:

Source: https://www.congestion-pricing-tracker.com/ … but at the moment I can’t get it to load. Probably lots of advocates updating their views by the minute.

This is important. The new regime in Washington may figure out a way to turn the system off, but they can never erase the data that it produced. And if it goes as it went on London and Stockholm, by then some people will already be saying it’s not so bad, and that it sure is nice to have Lincoln Tunnel moving!