Is your transit agency succeeding? It depends on what it’s trying to do, and most transit agencies haven’t been given clear direction about what they should be trying to do. Different people have different goals for transit, and those goals lead to different kinds of network.

To see why, look at this little fictional town. The little dots indicate dwellings, jobs, and other destinations. The lines indicate roads. Most of the housing and destinations in the town area concentrated around two main roads.

Imagine you are the transit planner for this fictional town. The dots scattered around the map are people and jobs. The 18 buses are the resources the town has to run transit. Before you can plan transit routes you must first decide: What is the purpose of your transit system?

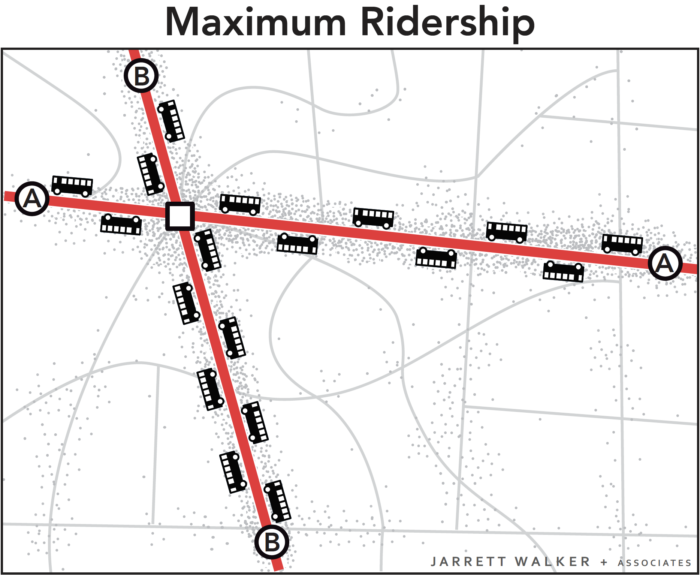

Designing for Ridership

A transit agency pursuing only a ridership goal would focus service on the streets where there are large numbers of people, where walking to transit stops is easy, and where the straight routes feel direct and fast to customers. Because service is concentrated into fewer routes, frequency is high and a bus is always coming soon.

This would result in a network like the one below.

All 18 buses are focused on the busiest areas. Waits for service are short but walks to service are longer for people in less populated areas. Frequency and ridership are high, but some places have no service.

Why is this the way to maximize ridership? Frequency tends to have huge payoffs. Most people find a bus coming every 15 minutes to be more than twice as useful as a bus coming every 30 minutes. Frequency also makes it easier to change between buses, which expands the range of destinations people can reach. So when we concentrate frequency where the most people will benefit from it, we tend to get the best ridership results. If you want to read more about this, see here.

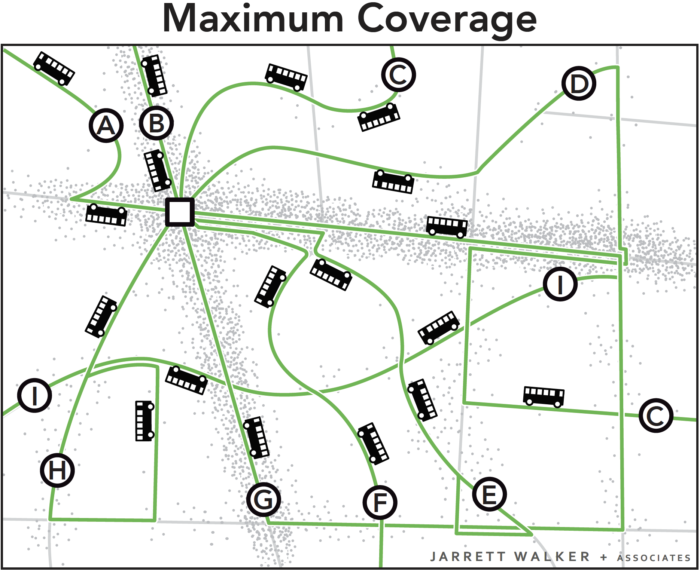

Designing for Coverage

A network designed only for ridership would not go to many parts of the city at all. If you think a transit agency owes some service to everyone in the community, you want a network designed for coverage. To achieve this goal, the transit agency would spread out services so that there would be a bus stop near everyone. Spreading it out sounds great, but it also means spreading it thin. The resources would be divided among so many routes that it wouldn’t be possible to offer much service on any of them. As a result, all routes would be infrequent, even those on the main roads. Infrequent service probably isn’t coming when you need it, so it isn’t very useful, so not many people would ride.

The 18 buses are spread around so that there is a route on every street. Everyone lives near a stop, but every route is infrequent, so waits for service are long. Only a few people can bear to wait so long, so ridership is low.

(By the way, in the coverage network I could have used on-demand or “microtransit” vans instead of buses on fixed lines. This is another tool for providing low-ridership coverage service.)

In these two scenarios, the town is using the same number of buses. These two networks cost the same amount to operate, but they deliver very different outcomes.

Both Goals are Important

Ridership-oriented networks serve several popular goals for transit, including:

- Reducing environmental impact through lower Vehicle Miles Travelled.

- Achieving low public subsidy per rider, through serving the more riders with the same resources, and through fares collected from more passengers.

- Allowing continued urban development, even at higher densities, without being constrained by traffic congestion.

- Reducing the cost of for cities to build and maintain road and bridges by replacing automobile trips with transit trips, and by enabling car-free living for some people living near dense, walkable transit corridors

Coverage-oriented networks serve a different set of goals, including:

- Ensuring that everyone has access to some transit service, no matter where they live.

- Providing lifeline access to critical services for those who cannot drive.

- Providing access for people with severe needs.

- Providing a sense of political equity, by providing service to every municipality or electoral district.

Ridership and coverage goals are both important to many people, but they lead us in opposite directions. Within a fixed budget, if a transit agency wants to do more of one, it must do less of the other.

Because of that, cities and transit agencies that lack adequate resources need to make a clear choice regarding the Ridership-Coverage tradeoff. In fact, we encourage cities to develop consensus on a Service Allocation Policy, which takes the form of a percentage split of resources between the different goals. For example, an agency might decide to allocate 60 percent of its service towards the Ridership Goal and 40 percent towards the Coverage Goal. Our firm has helped many transit agencies think through this question. Here is an explanation of how this conversation played out in a typical US transit agency.

What about your city? How do you think your city should balance the goals of ridership and coverage? There is no technical answer. Your answer will depend on your values.

Further Reading

Jarrett Walker’s Journal of Transport Geography Paper, which first introduced this concept, is here.