[Update: Joe Cortright of City Observatory has published a critique of this study]

When Uber or Lyft starts serving a city, more people die in crashes. This is the horrifying finding of a new National Bureau of Economic Research (NBUR) paper by John M. Barrios, Yael Hochberg, and Hanyi Yi. From the abstract:

We examine the effect of the introduction of ridehailing in U.S. cities on fatal traffic accidents. The arrival of ridehailing is associated with an increase of approximately 3% in the number of fatalities and fatal accidents, for both vehicle occupants and pedestrians. The effects persist when controlling for proxies for smartphone adoption patterns. … These effects are higher in cities with prior higher use of public transportation and carpools, consistent with a substitution effect, and in larger cities. These effects persist over time. Back-of-the-envelope estimates of the annual cost in human lives range from $5.33B to $13.24B.

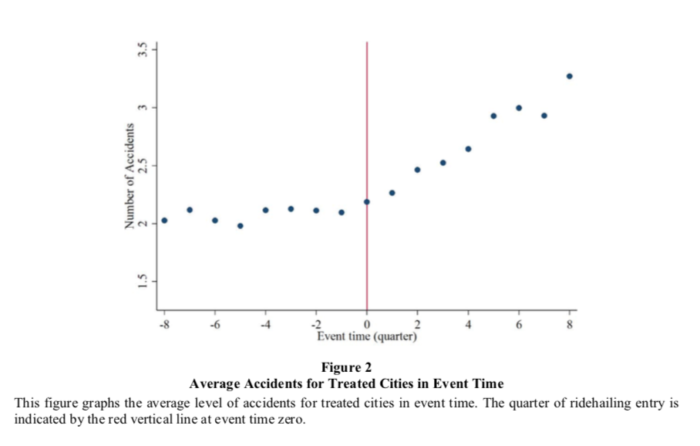

This chart says it all:

For each of the studied cities, the vertical red line represents the arrival of Uber or Lyft (whichever arrived first) and the dots are the traffic accident rates. The rate not only starts going up after Uber or Lyft arrive. It is still going up two years later. The paper goes into great detail, separating out possible related causes such as increasing cellphone use by motorists. The correlation is pretty strong. It is true of both the number of crashes and the number of people who die.

The authors find other evidence that isolates Uber and Lyft as the cause. In particular:

… the effect is concentrated in [ridehail]-eligible vehicles (relatively new, four-door vehicles) and is not present for accidents involving [ridehail]-ineligible vehicles (two-door vehicles). [p5]

One common selling point for Uber and Lyft is that they reduce drunk driving, but on balance, no:

We find that accidents and fatalities related to drunk driving do not decrease [after the arrival of Uber or Lyft]: if anything, we find evidence of a small increase … [p5]

I hope this all isn’t true, but if it is, it matters.

A few factors probably at work here.

Shifting trips from public transit to Uber or Lyft — which is definitely happening in major cities — means more than just increasing traffic. It means shifting people from a very safe mode of transport to one that is more dangerous, to the customer and to others on the street.

It’s not just that big transit vehicles are more crashworthy. Your bus driver has been selected and trained for safety, and is probably randomly tested for drug and alcohol use. Bus drivers also have training in anger management, so they know how to control the strong emotions that come up as things happen in traffic.

Uber and Lyft promise you none of these things. Drivers must have a clean driving record and criminal record, but beyond that the only promise of safety (for yourself and others) is that dangerous drivers get low ratings. What’s more, customers demand contrary things with their ratings. I give a low rating for driving over the speed limit in cities, because I value human life, but others might give a low rating for driving so slowly.

What I find, as a frequent user of both transit and Lyft, is that the safety of Lyft drivers is very diverse, and that the bad ones are very bad. Safety also varies dramatically by region. At home in Portland I rarely get a driver whose phone isn’t mounted on the dashboard, but when I use Lyft in Texas and Florida, most drivers have the phone in their laps, and drive along looking down.

Uber and Lyft are very useful, but we are learning more and more about their negative impacts: higher traffic, weakening support for essential public transit, and now, well, more people dying. Where does this end?

Putting that phone on the dashboard, or blocking the windshield, is hardly an effective safety alternative, though. And who hasn’t seen a ride-hailing driver even in Seattle or Portland earn that fifth star by blocking a bike lane or sidewalk?

Yes, definitely and many drivers are under massive pressure to drive fast. I’ve given so many 0 stars for incredibly dangerous driving. One driver in London had three near misses close passing cycles within a mile. Others have stopped in cycle lanes for pick up where a legal car park was available just 5 yards away.

ZThe only positive of uber over a taxi is that a 0 star rating for dangerous driving actually affects the ability of driviers to earn fares.

It should be possible for the taxi companies that pretend they aren’t to use the app on the phone (which has a GPS) and a database of speed limits to automatically downrate and eventually ban habitual speed limit breakers.

Could even compare with ratings passengers give and stop counting ratings of those who give speeders 5 stars.

I don’t use Uber and Lyft very much, but I still value the service and want it there when I need it. My typical Uber/Lyft ride tends to be around 10 miles, at an off-peak hour, mostly along an uncongested freeway. These are the kind of trips where taxis really tend to rip you off, as the fares tend to be mostly distance-based, rather than time-based.

Just a note on terminology. Those of us who work in road safety do not refer to accidents, but crashes.

The word accident implies that nothing could be done to prevent the outcome, whereas new approaches consider the whole system (the road, driver, vehicle and speed).

Also, this seems horrifying indeed.

I second Murray’s point. “Accident” suggests that nothing could’ve been done, whereas data shows that the vast majority of crashes is due to human error and could have been prevented. So we call them “crashes” or “collisions”, but not “accidents”.

These findings are not surprising to me. We already know that TNCs increase VMTs, which means higher exposure for all road users. Conversely, we’ve seen declines in traffic fatalities when gas prices are high because people drive less.

The two things I’d be interested in, though, are these:

Are ride-hailing drivers at higher risk of collision than average? We’d need to know their rates of collision – i.e. collisions/mile traveled or something like that. Not only do they have phones mounted on the dashboards, they often are not local to the city where they’re driving and are often not familiar with the streets (e.g. drivers who live in Sacramento coming down to SF, not familiar with the grid of one-way streets).

Does the increase in fatalities disproportionately affect vulnerable road users – i.e. peds and cyclists? I would suspect “yes” because the increase in VMT we’ve observed is on city streets, not freeways.

In Portland Oregon there is .50 surcharge to the passenger for every trip generated in the City of Portland , city makes millions , they are so awash with cash ,that they don’t know what to do with it , do you think they care about some death reports ?

Motivation and spontaneity may be factors as well.

Public transit drivers are on a pre-defined schedule and are paid by the hour, with little incentive to rush. Stopping places are predefined and marked. Their route is pre-defined with steps taken to ensure the road meets system standards, including for the safety of passengers and other road users such as pedestrians and cyclists.

User-directed drivers (ride hail and taxi) have incentive to complete the trip and move on to the next one to optimize their pay. They may also receive an extra explicit or implicit instruction from the passenger to get there quickly. They may select a route and stopping places based on their perception of how fast or direct it will be, even if the roadway or conditions are not optimal for the safety of pedestrians, cyclists or other road users.