Covid-19 has understandably caused steep declines in public transit demand, but the pattern of that fall is important. Peak (rush hour) demand has fallen much more than all-day demand, mirroring a change in travel demand overall.

This chart is from the daily updates we’ve been getting at the Transit app website. This chart covers all Transit clients, who are heavily US and Canadian agencies but include a few in other countries.

[Caution: These are not ridership statistics. Instead, Transit counted queries of its app, which provides realtime information about when the next bus is coming and, in some cities, can be used to pay your fare. That means this metric probably undercounts relatively unwired people, including low income people without smartphones and those less comfortable with apps. Still, it’s the only data that can be collated and updated so rapidly.]

Of course people are working at home during the emergency, but some leading companies are planning to continue the practice, and nobody really knows how much office work will return. You can see conflicting reports on whether working at home is wonderful or terrible, so we can expect continued experimentation as people and companies figure out what they like. Still, with the virus lingering, it will be a long time before everybody is back in the office, and there’s room to wonder if they ever will be.

Why is the fall of the peak important? Running service only at rush hour is expensive, for three reasons.

- A vehicle must be owned and stored that isn’t used very much.

- A driver must report to work for just 2-4 hours, which is less efficient, hard on the driver and will cost the agency more per hour of service.

- Most peak demand is massively one-way in the morning and the other way in the evening. Drivers’ shifts must end where they began, so every bus or train that runs full in one direction has to return empty in the other, often over long distances.

So the fall of the peak, if it were sustained into the future, could be great news. While the peak is an easy place to rack up lots of ridership, its high costs mean it’s not always the best place to seek productivity (ridership divided by operating cost). Ultimately that means that there could be all-day markets that would be more productive once the high cost of peaking is taken into account.

There is also the large social justice dimension to the peak. Peak commuters are far more affluent on average than all-day travelers, because higher wage jobs are more likely to be “nine to five” while lower wage workers, predominantly in retail and services, are more likely to be needed around the clock. So a decline in peaking could help sustain services that support lower wage people — and remember, these are people whose work everyone depends on.

Of course peak service is justified by the need to mitigate traffic congestion that occurs at that time, but it remains to be seen what levels of congestion will return. It may go up if we try to run a full economy with social distancing, but it could also go back down after a vaccine. We’ll have to see.

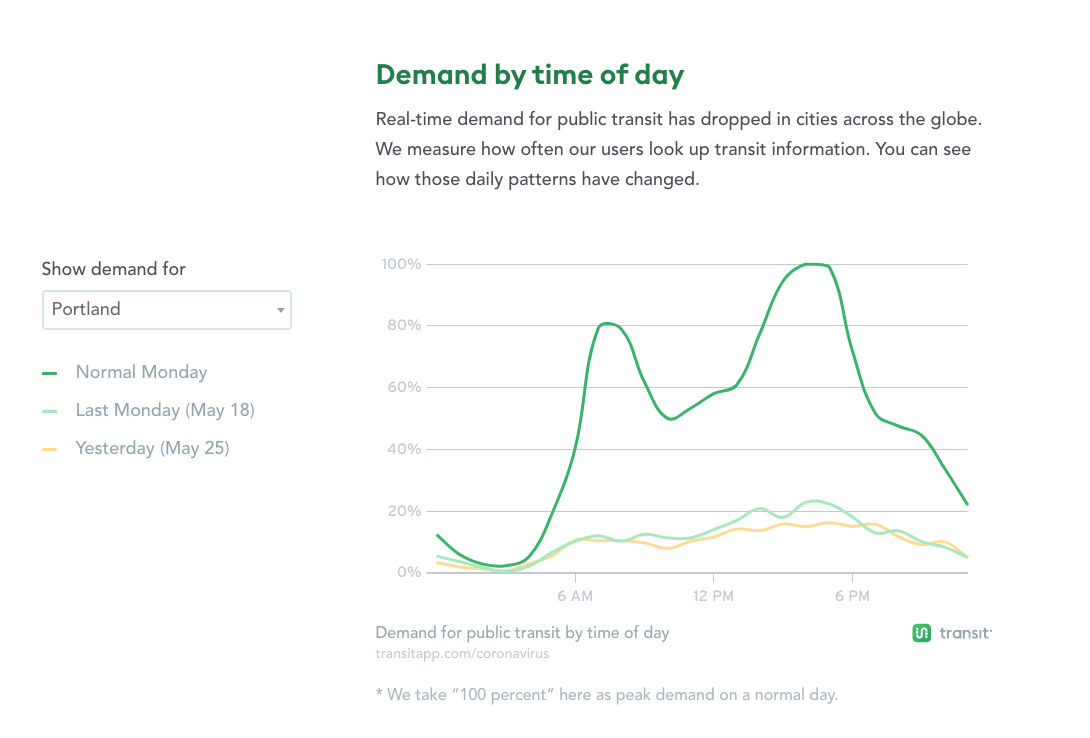

Peaking has such a huge effect on the life of a city, and the costs and efficiency of transit, that it’s worth taking a quick tour of how different it is in different cities, and how that reflects choices the city made — consciously or unconsciously. Here’s my home city, Portland.

This is typical of a lot of US cities where the social distancing expectations (both legal and cultural) have been firm over the last two months. The peak is mostly gone. In percentage terms, the difference isn’t huge. Ridership is down about 80% at both midday and PM peak times, but it’s down about 87% on the AM peak, where few people travel other than for peak work shifts and schools. Still, the absolute numbers matter too, because they measure the degree to which an agency will be forced to run expensive peak-only services rather than an all-day pattern.

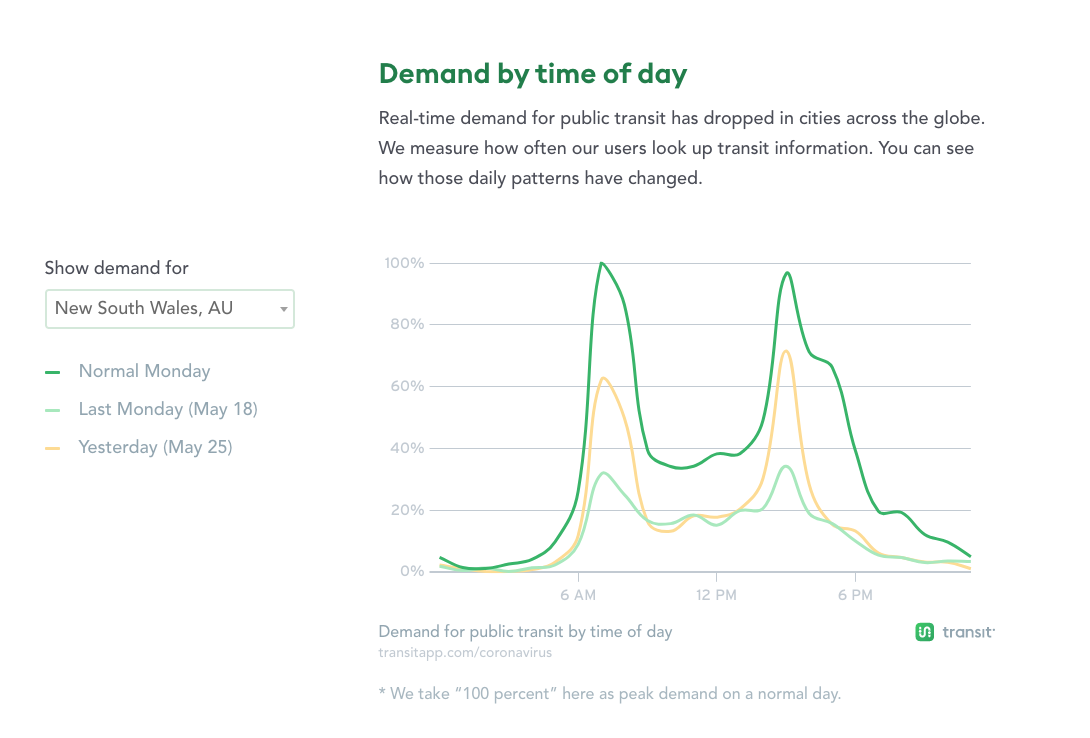

Note that this typical North American peak is about two hours long in the morning and three hours long in the afternoon. That’s the result of peak spreading, the widespread tendency for start and end times to vary slightly by employer (and by school). Compare Sydney, Australia [really this is all of the state of New South Wales, but Sydney is the overwhelmingly dominant market there]

Australian peaks are much sharper than North American peaks — less than two hours long — and as you can see from yesterday (May 25) they are coming back as sharp as ever. Australian public transit also does most of the work of school transportation, which explains why the afternoon school peak at 3-4 PM is bigger than the evening commute peak at 5-6 PM. Note that it is the school peak that is returning now, though, while the work commute peak — marked by activity in the 5-6 PM hour, is not so prominent.

When I worked as a transit planning consultant in Australia I was always struck by the huge cost of serving a rush hour that’s so brief. Yet Australia is far behind North America is adjusting work and school scheduling to spread the peaks out, so that demand (both transit and road) can be served more efficiently. (Spreading the peak can also create huge savings on infrastructure projects, since if you scale infrastructure to serve the peak one hour, you’ll need a lot more infrastructure than if the same demand is spread over two hours.)

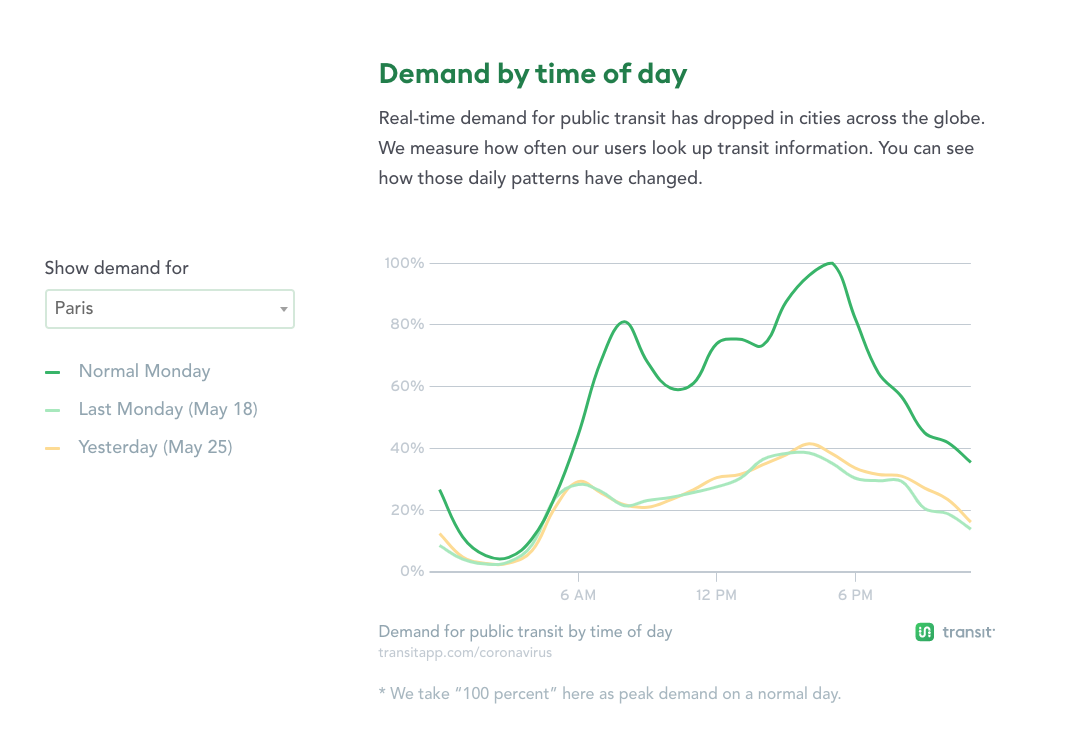

Now look at Paris

The abundance of transit in Paris isn’t just a matter of spending lots of money on it, but on focusing on an all-day demand rather than peak demand. Paris has plenty of peak commuters, but so many people rely on transit for all kinds of purposes that those peaks don’t stand out the way they do in less transit-oriented cities.

Of course, there are some car-oriented cities without much peaking either, generally those built around entertainment and tourism. Las Vegas, say:

This is what happens when you have relatively few rush-hour commuters to office jobs, but massive employment in tourism: shifts starting and ending all the time. But it’s not all tourism. All those jobs that keep society running — working at WalMart or a hospital or a (take-out) restaurant — are visible here because the commute peak doesn’t swamp them in the chart. Note how much smaller the drop is from pre-pandemic days: only about 50% compared to 70-90% in most US cities, because there were fewer peak commuters before. Even with the massive loss of casino and hotel jobs, plenty of low-income people need to get to work.

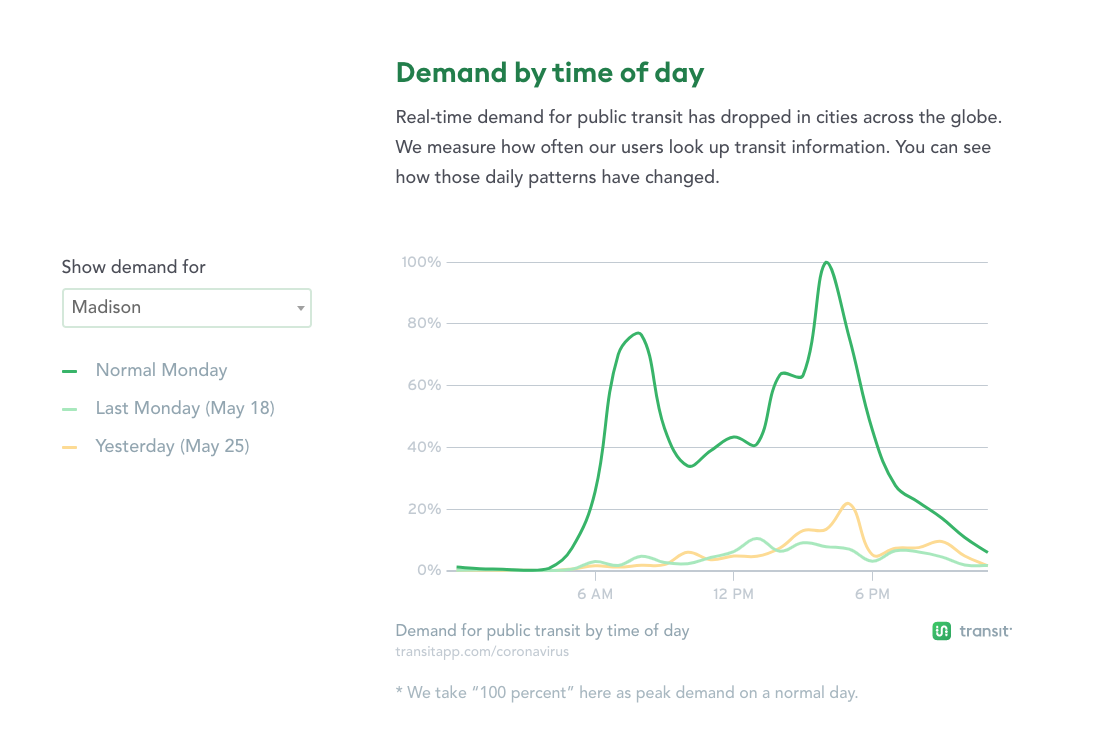

Finally, a small US state capital with a huge university. Universities tend to be huge consumers of transit, and you can see the effect of both university and state offices shutdowns in Madison, Wisconsin.

The drop was over 90%, and only the PM peak shows the earliest signs of coming back, now to 80%. [Again, these are Transit app queries, not ridership numbers that can only be provided by the agency.]

All these graphs are scaled to the pre-pandemic demand, so only in Las Vegas do you see the importance the low-wage worker in essential services including essential retail. But those people are in all of these numbers and are why there was any ridership at all.

Keep an eye on these charts, and on peaking patterns as they emerge in ridership data from the agencies.

I seem to recall reading that, at least in Seattle, some peak-hour drivers work part-time for the transit agency and park the bus downtown while they work so they don’t have to deadhead as much just to leave the bus where they started it all day. I definitely remember seeing long lines of buses from multiple agencies parked on Eastlake Ave when I lived there, but I don’t know if that’s changed.

Neil Peterson who was the GM in Seattle in the early 80’s would proclaim that there is nothing more efficient that a part time driver operating a full articulated bus into the center city during the peak. When he came to AC Transit where I worked for a short stint in 1988 I would have spirited discussions with him because we were in the process restructuring our service to better capture the non peak trips. His model was not sustainable then and definitely not sustainable now.

I’m worried, not so much about what’s happening right now, but what will happen when offices and schools start to reopen and peak commutes start to resume, but transit systems are incapable of adding anywhere near enough peak service to maintain a 6-foot social distancing between passengers on board its vehicles. Will we see agencies cutting off-peak service to the bone in order to raise money to buy one more bus and hire one more driver for peak service?

So far, the only real solutions I’ve seen proposed involve getting large employers to scatter start times and/or get a large percentage of their workforce to continue working from home. It will help, but I don’t think it will be enough. As the charts reveal, the baseline level ridership at 10 AM and 3 PM is far from zero, and even with all the buses running that were running previously (far from a given with inevitable recession-induced budget cuts), social distancing requirements will drastically reduce the capacity of the fleet.

It seems nearly inevitable that we’re going to end up with a lot of former transit riders picking up or returning to a habit of private car commuting. I’ve already talked to one person who’s employer is requiring everyone to avoid public transit when the office reopens, and is offering big subsidies towards downtown parking to ease the financial burden. (Of course, those that choose to walk or bike to work don’t get the subsidy, even those they are also avoiding public transit). If I met one such person, there are probably going to be many others. And it’s far from clear that they’ll end up going back to transit, once the vaccine becomes available, by which time, the habit of car commuting will become entrenched.

Perhaps we’re headed to some sort of equilibrium cycle where traffic simply piles up until people go back to working from home because they can’t take it anymore. One way or another, the roads simply cannot handle all of 2019’s transit ridership switching to private cars.

Some suburbs of Sacramento, CA have come up with a solution to the deadheading problem: they hire people who work in the city at other jobs to drive the commuter buses. The bus is parked in downtown Sacramento during the workday. After work, the driver picks up his/her peers and takes them back to the suburb. You can see many of these buses parked near the CA State Capitol during the day.