by Christopher Yuen

With only a handful of exceptions, transit ridership has stagnated or been falling throughout the US in 2017. The causes of this slump have been unclear but some theories suggest low fuel prices, a growing economy fueling increased car ownership, and the increasing prevalence of ride-hailing services are the cause.

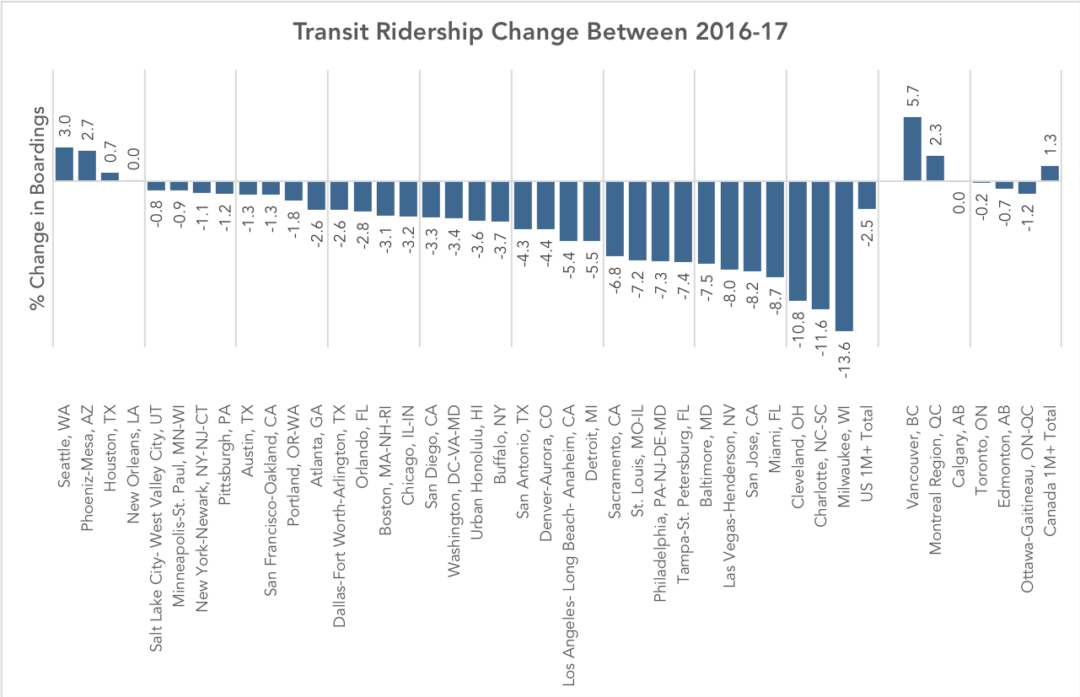

A few North American agencies have bucked the trend, including Seattle, Phoenix, Houston, and Montreal. By far the biggest growth was at Vancouver, BC’s Translink, which saw a ridership growth of 5.7 percent in 2017.

But notice the big picture: In a year when urban transit ridership fell overall in the US, it rose in Canada.

Transit ridership urban areas with populations of over 1M are included in this chart. Ridership of major agencies that serve the same region are added together. (Source: National Transit Database; APTA 2017 Q4 Ridership Report)

There are three interesting stories to note here.

1. If You Run More Service, You Get More Riders

Canadian ridership among metro areas with populations beyond one million is up about 1.3% while regions of the same size in the US saw an overall ridership decrease of about 2.5% in 2017 despite the broad similarity of the countries and their urban forms. Why? Canadian cities just have more service per capita than the most comparable US cities. This results in transit networks that remain more broadly useful in the face of competition from other modes. Note, too, that Canadian transit isn’t cuter, sexier, or more “demand responsive” than transit in the US. There is simply more of it, so more people ride, so transit is more deeply imbedded in the culture and politics.

2. Vancouver Shows the Effect of Network Growth, Higher Gas Prices, Great Land Use Policy, and No Uber/Lyft

Vancouver’s transit ridership has historically been higher than many comparable regions as a result of decades of transit-friendly land-use and transportation policies, including an early regional goal to foster density only around the frequent network. (The Winter Olympics also had a remarkable impact: ridership exploded in 2010, the year of the Olympic games, but then didn’t fall back after the games were over; apparently, many people’s temporary lifestyle changes became permanent.) By North American standards, Vancouver is remarkable in the degree to which development is massed around transit stations.

But Translink attributes its 2017 ridership growth to continued increases in service, high fuel prices, and economic growth. The 11km (7mi) Millennium-line Evergreen Extension just opened prior to 2017, directly adding over 24,000 boardings a day. Fuel prices in Vancouver have also reached an all-time high, at $1.5 CAD / litre (4.4 USD/ gal), an anomaly in North America, although still lower than in Asia and Europe. Economic growth has also been consistent, with the region adding 75000 jobs in years 2016 and 17. Notably, ride-hailing services like Uber and Lyft are not available in Vancouver due to provincial legislation.

3. There is Conflicting Evidence on the Impacts of Economic Growth on Ridership

Many commentators suggest economic growth to be a factor of the 2017 trends in transit ridership but there seems to be two conflicting theories, with economic growth cited as both a cause ridership growth and a cause of ridership decline. The positive link is obvious- economic growth leads to more overall travel, some of which will be made by transit. Contrastingly, the negative link is based on the theory that increasing incomes allow for more people to afford cars. Both theories seem plausible, but for both to be true, the relative strength of each must differ between cities.

Most likely, economic growth in transit-oriented cities is good for ridership, and growth in car-oriented cities, which encourages greater car dependence and car-oriented development, is bad. This would explain the roaring success of Seattle, Vancouver, and Montreal, though it doesn’t explain why Houston and Phoenix are doing so well.

As North American cities work to reverse last year’s losses in ridership, they may best learn from Canada, and a select few American cities, to leverage economic growth for ridership growth.

Postscript by JW

For Americans, Canada is the world’s least foreign country. There are plenty of differences, but much of Canada looks a lot like much of the US, in terms of economic types, city sizes and ages, development patterns, and so on.

So why is Canada so far ahead on transit? All Americans should be asking this. Ask: Which Canadian city is most like my city, and why are its outcomes so different? We’ll have more on this soon.

The Toronto Transit Commission has been consistent underfunded for over a decade, and the results show in the ridership loss. This is despite the booming Toronto economy, the city’s high livability and vitality rankings, and generally positive press. In another way, Toronto is also a victim of its own success – buses are slower than ever, crowded by more vehicles and Uber/Lyft companies.

The King Street Pilot is a great initiative to prioritise transit vehicles and increase ridership, but the Mayor is refusing to direct Police to better enforce its driving restrictions.

Ridership expansion projects, like the recent Line 1 subway extension, are exclusively in the suburbs for political reasons. Fortunately LRT lines are under construction, but are in real danger if Trump-like Doug Ford becomes premier.

The Toronto numbers may not be an accurate representation because they don’t account for the double-double – digit growth of their GO system, nor their UP Express train which canabalizes ridership in the city’s ‘west end’

Anecdotally, I have peers in Toronto who told me they made the switch to GO trains coming from the northern York area, instead of Ttc Subway because they introduced frequent service on GO lines.

Also worth adding, Ottawa’s numbers likely declined only because of the major construction of the new subway line. I would imagine ridership will soar when it opens next year(?)

Well turns out Toronto was using a different methodology for calculating ridership that vastly underreported the ridership there. They’re actually experience massive growth rather than a slight decrease if they use the same unlinked trip methodology of all the other cities. So the disparity between Canada and here is probably even broader.

I think Phoenix’s increase in ridership is due almost entirely to reason #1–Phoenix’s increased bus service kicked in in October, 2016. The sales tax increase Phoenix voters approved to fund transit resulted in improved frequency and three full hours of additional service on every local bus route every day.

See e.g. https://www.phoenix.gov/news/publictransit/1859

Just on the growth or decline issue in point 3: it sounds like the standard economics decomposition into income and substitution effects. They can point in opposite directions, with the observed change being a combination of the two. So, economic growth makes people richer and they buy more stuff (growth). However, they also buy a different basket of goods because of the different income elasticities of goods, and that can lead to decline in the proportion of spending on a good. Also, add in that cars (+insurance+garaging) are lumpy goods. From a straight theory perspective, it isn’t clear whether to expect ridership to go up or down.

It is not just the transit service levels that set Canadian cities apart from American ones.

A big reason for better transit usage rates in Canada, that would be nice for you to touch on, is that transit is provided to almost all areas in a given urban area – the coverage is good. In most Canadian metropolitan regions, you can rely on transit in the suburbs and inner city, meaning transit is a useful service for everyone, and gets buy in from across an urban region.

Contrast this to American cities, where outlying areas and suburbs often receive little or no transit service, and you can see why ridership lags. Even Portland, for example, has very poor bus service in outlying suburbs. This is one of the reasons ridership in Portland is vastly lower than comparable cities like Vancouver, or smaller cities like Calgary or Edmonton.

mb … While it’s nice to have service everywhere, I disagree that suburban service is a dominant force in systemwide ridership. Translink turns in predictably low ridership in its lowest-density fringes and pockets. Its success lies in its high mode share in high density areas — and the abundance of those areas.

I should clarify that by “suburban” in that comment I don’t mean downtown Surrey, I mean hills and low-density suburban fringes.

Folks outside the Northwest should be aware that Richmond and Burnaby BC, at least along the rail transit corridors, are denser than the majority of U.S. cities. That’s no accident. From my colleague David Gutman:

https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/transportation/seattle-struggles-with-growth-and-transit-while-vancouver-b-c-figured-it-out-years-ago/

As you know Jarrett, we disagree on this.

You judge the strength of a transit system by service on the weakest parts of the system.

The reason Toronto, for example, has amazing transit ridership, is not because of the service in the inner city. It is because you can stand in the most isolated neighborhood in north eastern Scarborough and get a bus every 10 minutes, deep out in suburbia. The ridership success of Toronto comes from the suburbs, and it is the same in Vancouver. If Translink provided dismal service to the suburbs, then Vancouver would not be doing as good as it does in the transit department.

The fact that the road in the link below gets bus service better than most major suburban roads in suburban America is why transit is so good in Vancouver, and why people use it. They can use it, because they can travel wherever they want, including this far off, isolated community. And it makes the high ridership areas stronger, because they have even more riders feeding into it from these lower ridership services.

https://www.google.ca/maps/@49.3190789,-122.9267152,3a,75y,10.82h,89.54t/data=!3m6!1e1!3m4!1spSX2AvAZ9FDICO4hd6d54g!2e0!7i13312!8i6656

mb:

What data or factual information do you have to back up your claims? It seems you assume people are separated into the classic choice and dependent riders. People have choices on mode, depending on where they are going. Even poor people have options besides transit, and if it gets bad enough (or there simply isn’t an option aka low density areas that may not have fixed route transit), they may get a ride from a friend, or a taxi/ridershare if it is really important, or walk, or bike, or drive themselves. It is not the job of any single mode to necessarily serve every single resident at close distance because this is not cost-effective. You also contradict the general geometry of transit, twice the density at the same rate is twice the riders. end of story. Paying attention to peoples’ behavior is important too, for sure, but I think you have misjudged transit’s effective role and also I have reason to believe riders in low density unwalkable areas will actually use transit at a lower rate.

https://www.translink.ca/-/media/Documents/plans_and_projects/managing_the_transit_network/2016-TSPR/2016-TSPR-Appendix-C1-Routes-001-099.pdf?la=en&hash=C6E768A5DE629AE7E6B6ED8E6B3459BC166527B2

https://www.translink.ca/-/media/Documents/plans_and_projects/managing_the_transit_network/2016-TSPR/2016-TSPR-Appendix-C4-Routes-C1-C99.pdf?la=en&hash=F4C03FDF946CFEB516D7D8DC36F043C95DF1D8DA

^ last I see, Vancouver’s transit performance is measly in the burbs and high ridership in the frequent, dense corridors..

I could not locate the exact routes you linked to but the C48 in the east serves a similar landscape and operates at around 5-10 passengers per hour, with 0% of trips being overcrowded. The 099 serves the dense Broadway Corridor at around 160 passengers per hour with about 80% of trips being overcrowded. But this extends to virtually all routes, as a general rule.

Most of the riders in Vancouver are on the main routes, and good service in the periphery may be a byproduct of the abundance of transit overall, it is not necessarily the cause of this ridership. Correlation does not equal causation.

Your argument is basically the network effect argument, and I would think this applies more to frequent, fast, reliable routes rather than infrequent services which do not provide the same freedom to move.

I think you’re both saying the same thing: Canada has higher levels of transit across the board, both in inner-city areas like Vancouver, and in major suburbs like Burnaby and Surrey, and in single-family outer areas like down toward White Rock. That’s more like European service, where you can get to anywhere in the country on transit, both cities and suburbs and towns, at least hourly in the major towns and a few times a day in the smallest towns. It may not reach far-flung isolated houses, but once you get to a park-n-ride it’s smooth sailing from there to anywhere in the city or suburbs.

In contrast, while Seattle has had major improvements and more are coming, there are still not-so-small trip pairs that take an hour on transit even to go just five miles in the city or large burbs if your trip isn’t along a single bus route. I.e., anywhere in northeast Seattle north of NE 50th Street to downtown or northwest Seattle. Ballard to Capitol Hill. I’m one who always takes transit even if it’s difficult, but when I hear about some of these trip pairs I can’t really recommend transit strongly, and I myself avoid those areas as much as I can. (“If it’s not on a frequent route, I don’t go, except occasionally.”) Most of the US has even less bus service than this, so consequently it’s hard for the majority to consider transit, especially since what they’re used to is cars.

Great stuff Mike. It would not be that difficult physically to put bus lanes on N 50th, rather than just suffer and pray for light rail in 2050 or so crosstown.

Compare the Seattle and Vancouver regions: Seattle has many employment centers; sprawling, low-density bedroom communities; de-regionalized planning; a small light rail system; multiple transit agencies; a large freeway network, and a large geographic area. Now Vancouver: relatively dense housing, even in the bedroom communities; just a handful of employment centers; a single, integrated transit system, a relatively compact urban form, relatively few freeways, and strong regional planning that is backed up by other government policies at the provincial level. On top of that, living costs are relatively higher, so that for a large number of young people, living “carless” is not only convenient but economically essential

The point is that Canada and Europe have a higher level of transit across the board regardless of each metro’s population distribution, jobs distribution, or walkability. Those latter three factors explain some of the higher ridership but not all of it. There is a point of diminishing returns with transit investment, and while Canadian and European cities may be right at it (maybe), American cities are well below it. Of course there are issues with effective transit investments vs ineffective ones, but even that is a secondary issue. The ultimate fact is that while some people choose not to take transit that exists, there are more people who want to take transit that doesn’t exit (or would want to take it when they see it running on the ground).

>> Of course there are issues with effective transit investments vs ineffective ones, but even that is a secondary issue.

I disagree. Spend the money the wrong way, and you will need to spend the money all over again (and most cities can’t afford that). Toronto has made one (relatively small) expansion in the last twenty years, while New York has done the same. Likewise with BART. The difference is that New York and Toronto have very popular, very effective subways, while BART has wasted much of its money serving far flung suburbs. BART has twice as much rail as Toronto, yet the outcomes are much worse. Do you really think Toronto is about to double their track mileage and catch up with BART? Do you think San Fransisco is ready to make another major investment in a subway, and finally do it right this time?

Yet San Fransisco looks like a paradise compared to Dallas. They have the longest light rail system in North America — a whopping 93 miles — yet less than 100,000 riders a day, making it one of the worst systems in ridership per mile. Denver isn’t much better. These are cities that struggle with providing good basic service on the lines they have — you can’t expect them to go back and do it all over again.

Because they won’t. It matters how you spend the money. Seattle spent a fortune sending rail down to the airport, and had very low ridership. Then they added two stops, and practically doubled ridership, because those two stops were in the core of the city. Now they are following the lead of Dallas, and building rail to different cities, hoping that the results will be better. The result will be an extremely expensive system that will perform poorly on most metrics, even the optimistic ones released by the agency in charge (https://www.thetransportpolitic.com/2016/04/06/youve-got-50-billion-for-transit-now-how-should-you-spend-it/). That means that transit won’t be very good, despite the enormous investment. That is nothing unusual — there are plenty of cities that have done worse. The problem isn’t just lack of investment, but making really, really poor investments.

Canadian land use is far more transit-supportive than typical US land use, which I believe is the underlying reason for better transit coverage, better ridership and higher service levels. Even outer suburban areas in Canada are more likely to average 12 units/acre, instead of <4 units/acre across vast swathes of US suburbia.

Urban fringe development seems to be more orderly and well-planned in Canada, with defined urban frontiers and no urban services, such as sewers or transit, beyond. Sure, in photos it can look similar to US suburbs, but an aerial view or a population density map reveals significantly more intensity in Canadian suburbs.

Transit levels and ridership ultimately come down to decisions by the authorities and voters and riders; it’s not directly tied to land use. Two areas with the same density can have different levels of transit and ridership depending on people’s attitudes toward transit, taxes, and cars. It’s likely that the attitudes caused both the density and the level of service. But how that plays out depends on a hundred different attitudes, not just two or three. Cars in the US were seen as part of the American Dream and American freedom, and suspicion of cities and governments has always been higher than average. Canadians may have aspired to cars but it’s hard to see them as identifying it with the Canadian Dream, or as what distinguishes them from inferior Old Europe.

Also, critically, Canadians don’t view transit as a public service for the poor like we do, probably everywhere but NYC. And, it matters that Canadian transit is often marginally ‘sexier’ than ours. Just in terms of branding and customer experience, there is more effort put in. Look at Montreal’s http://www.stm.info or Toronto’s http://www.yrt.ca . There’s at least an effort to look modern and attractive, unlike here where transit branding is invariably an afterthought and it looks cheap. I think this applies to most government services in Canada vs here in general. Branding matters there, here it’s a cost waste.

Yet somehow Calgary (https://goo.gl/maps/STR6UcHSj1o) manages to have more riders on its light rail system than any U. S. city. There are plenty of U. S. cities with higher ridership on heavy rail, but Calgary’s numbers are still amazing, given the population density.

While many of the systems (like Vancouver and Toronto) don’t surprise me at all, I’m baffled by Calgary. Somehow they manage to have very high ridership, despite many of the stops being in the middle of nowhere. From what I’ve read, there are a number of factors, but one of the biggest is a downtown area that dominates local commerce, and is difficult and very expensive to access via a car. Most of the jobs are right downtown, but if you try to drive there, it will take a while, and cost a bunch for parking. It is also possible that a huge portion of the riders are simply going from one end of downtown to the other — a trip that is free and easy (since the stops are on the surface).

Calgary, like Vancouver, has no freeways that go into or through downtown, and never will. This is a pretty big deal, as, like you say, it is slow and expensive to drive there.

Interesting, as I had always though Alberta was very conservative area in Canada. Very surprising to see Calgary’s modal split for the city center is close to 50 percent!

Calgary has it both ways. Typical Calgary commute is driving to a train station, and then taking the train downtown.

Calgary is unique in that almost every job in Calgary, is in downtown Calgary, and there is only so much parking in downtown. They have so much urban sprawl that buses are too thin in the suburbs, yet not nearly enough parking in downtown, so the end result is this driving+train commute.

Land use, cost of parking, political service priorities, all matter. In Calgary, downtown parking is exceptionally expensive – it was once the most expensive in all of Canada, and second in North America. This makes transit an economic choice.

Also not noted in the article – Houston recently restructured its buses to include a much larger frequent network – including a “frequent” network that is now frequent 7 days a week, instead of just Monday-Friday. The fact that Houston’s ridership has been increasing while the rest of the country was decreasing is good empirical evidence that the restructure is working.

If quality transit is what prevents ridership from declining, why is it that even American cities with good transit service (by American standards) declined in 2017?

The articles does not say quality transit prevents ridership decline. It states it is a component in preventing ridership declines. You probably ALSO NEED rational land-use policies (which … does any American city have that? certainly not mine), economic growth, and possibly effective regulation of heavily subsidized [venture capital is a subsidy] alternatives (Uber, Lyft, etc…)

American cities desperately need land-use policy reform for this any many other reasons. But I do not know any credible person who believes that is going to happen – land use policy in American cities is the third rail, nobody dares touch it. We tried in my city recently, and it was an excellent example why it is impossible.

“Land use policy” mostly means Euclidean zoning in American cities. The main reason(s) why it’s locked in place are:

– Changing it would primarily benefit people who don’t already live in the area and thus can’t vote.

– If density increases, the locals (who can vote) lose part of the club good of living in a “sleepy area”.

– Locals don’t understand the real estate market, in particular that if their plots zoned for single-family housing are upzoned to e.g. two-family, then the price of their land approximately doubles.

– It is primarily developers who lobby for changing zoning. But because usually they need to buy and demolish the house already standing on the plot, it’s much more profitable to build a 6-apartment condo in its place, rather than a duplex or something similar. However, that’s a really large step up in density, and it *looks* very different from the existing single-family houses, so locals are often much more opposed.

– It is not unusual that the locals and the developer eventually make a bargain where the developer has to build some nicety for the locals (such a small park) in return for getting the variance. However, the cost of this nicety gets built into the price of the new housing units, making them more expensive than they are worth (looking purely at the land and construction cost).

– Vocal, socially-concerned people don’t understand the market. Because in the cities with housing shortages (very high rents and unit prices), the need for zoning variances strictly limits the QUANTITY of new units that can be built, the developers build for the high-end market. That’s because if a developer can use a given amount of lobbying (expense) to get the right to build, say, 100 new units, he will seek to maximize per-unit profit. If the quantity limit was very high or nonexistent, the developers would quickly glut the high-end market and proceed downwards—but alas, that is not to be. Because developers build for the high-end market first, socially-conscious people oppose new construction because that causes gentrification, making construction opportunities scarce and driving housing costs up. They mean well, but their mistake nonetheless backfires. 1) It is an obvious rule of thumb that if more houses could be built in a city, while the population i.e. demand for housing stayed the same, the average price of houses would decline. 2) In particular, even if developers only build for rich people at first, the rich people who buy the newly-built houses move out of their old house. Some of them sell it to an upper-middle-class family, who move out, sell to a middle-middle, who move out and sell to lower-middle, etc. While this effect is greatly diluted as it proceeds, both because “society is pyramid-shaped” and because some people don’t sell their house when they move to the new, it nonetheless exists. This is how old inner suburbs, that had been solidly middle-class when they were built a hundred years ago, have often become low-income regions.

– Faced with an idea they don’t thoroughly understand, people tend to be “conservative” in the sense that they prefer the status quo to the new idea they treat as risky. This is often useful, because they don’t fall for conmen, but at the same time make the job of reforming broken systems much harder, e.g. introducing congestion charge, abolishing Euclidean zoning, etc.

– It is often theorized that the reason zoning came into existence in the first place is to create areas with homogeneously expensive housing, and thus segregate by socioeconomic status (as a proxy for segregation by race). While that’s bad, each neighborhood tends to consist of people of similar socioeconomic status, which can be viewed as a good thing; even if society as a whole has huge inequality, each community could be reasonably equal inside.

Land use policy is gradually changing, some areas more so than others. In 1990 there were practically no new urban villages — just prewar density that had remained. Now practically every city and a growing bandwagon of suburbs have new or densified urban villages — even Atlanta and San Jose — and they consider them essential to avoid being left behind economically and to manage a growing population. Exurban developments — “new urbanist” townhouses, close-together houses, with their own retail district — are increasing, not decreasing. I was stunned at what I see in the suburbs: I thought people moved to the suburbs to get quarter-acre lots and wouldn’t tolerate city-like density so far out, but there it is and they’re buying them. There’s still the biggest elephant in the room — the refusal to upzone single-family areas that are 75% of most cities’ residential land — but it’s slowly being chipped away decade by decade. You look at people’s red lines now, and they’re different from the red lines of twenty or forty years ago. The trend is that they’ll continue to urbanize, and that more people will be OK with it.

“It is not unusual that the locals and the developer eventually make a bargain where the developer”

Upzoning does not force densification. It *allows* willing homeowners to densify their land or sell to developers if they want to. It’s about increasing people’s freedom and individual property rights, and returning toward an earlier norm.

“While [de facto race-based zoning] is bad, each neighborhood tends to consist of people of similar socioeconomic status, which can be viewed as a good thing; even if society as a whole has huge inequality, each community could be reasonably equal inside.”

Even if it improved some aspects, it arguably created greater problems than it solved. In the ancient and medieval world the rich and poor were shockingly unequal by today’s standards, but they both lived in the same neighborhood because the gentry needed servants and farmworkers before the era of electrical appliances and commuter transportation. Now the various classes and social groups live in different worlds and don’t even see each other face-to-face, and children grow up with no experience or interaction with people who are poorer, richer, better educated, worse educated, or a different color from them. They may have minimal contact here and there, but not enough for a complete understanding or fully-informed decisions like medieval lords and their peasants had. In “Flambards”, a TV miniseries, a girl in 1905 England goes to live with rich relations, marries her cousin in the house, and has a crush on a farmboy (whom she marries after her husband is killed in war). She doesn’t understand why the farmboy can’t overtly say he knows she likes him and he likes her, but her husband-to-be has lived in the community his whole life and understands what things look like from the working-class-people’s perspective, even though he by social convention also can’t be as friendly or egalitarian to them as he might like to be. Whereas if they all lived in 2018 rather than 1918, the rich family and the poor workers would live in different neighborhoods or cities and never even see each other or understand each other’s culture or experience, and this leads to false assumptions growing unchecked.

Some American cities may have “good transit service” by American standards. However, that does not mean these cities have been investing in new and improved transit services. So the ridership declines are likely a cause of no investment in transit service, coupled with probably some minor cuts to service over the past few years.

While these cities may have “good transit service”, it is still by “American standards”, and that means transit services are still not always up to par for keeping riders with a choice.

An example of this is my friend in Chicago. Despite pretty good transit, he has to rely on a bus to get to his on the edge of downtown job, that does not run very frequently, despite being in the core of the city. He has defected to ride sharing and bike sharing for his commute.

Legacy transit cities like NYC, Boston, Chicago, Philly, have invested very little in their transit networks. They have ridden a ridership growth spike due to excess capacity and recentralization of jobs downtown. But without continued improvements, they can’t sustain ridership growth.

In the Toronto area, the TTC, due to funding constraints, has not improved service much over the past year or two, and ridership is stagnating, while it is booming in some of the surrounding suburbs, where service has been improved. No different from the legacy American cities which have not invested in service. And almost all the cities in Canada that saw ridership declines have not invested in service the last year or two. The ones that have invested in transit service have continued to set ridership records.

“An example of this is my friend in Chicago. Despite pretty good transit, he has to rely on a bus to get to his on the edge of downtown job, that does not run very frequently, despite being in the core of the city. He has defected to ride sharing and bike sharing for his commute.”

Why can’t your friend ride rail to downtown, then walk from there? Chicago is very walkable, and you say he’s willing to bike the whole way, which is way more strenuous than walking. No part of “the core of the city” in Chicago is unwalkable. Even River North, West Loop and South Loop – parts of which do have poor rail connectivity – are within at most a 15-20 minute walk of a rail station with sidewalks everywhere.

I’ll just dispute the idea that biking is “more strenuous” than walking. The reverse is mostly true. Where biking is more difficult than walking is typically where road conditions are highly unfriendly which Chicago has made good progress on. I’d also argue that bike share is transit and planners and agencies would be smart to think of it as such.

Because of American standards. There’s a difference between cities with comprehensive transit like New York, Chicago, DC, Boston, San Francisco (city), parts of LA, vs all the rest. The cities with comprehensive transit have high ridership, and where it’s declining it’s often associated with the deteriorating quality of unmaintained subways or the slowdown of buses due to increased traffic. In other cities that have a lower level of transit service, where 15-minute segments only exist on one or two streets, the hours are wasted on infrequent parallel routes, or the span is short — even if the level is above average by American standards, it’s still not practical for the bulk of people to use, so they buy a car as soon as they can. Some people don’t, but a lot of people do, and that’s the low or declining ridership right there.

Many smaller cities in Canada have had amazing transit ridership growth in recent years.

My city, Kingston, ON with a metro population of just 150k, has had ridership grow by double digit percentages every year since 2014 with annual ridership exploding from 4 million in 2013 to 7 million in 2017. The root cause is extensive investment in bus service, combined with the city increasing its parking rates in the downtown (both public lots and through taxation, private lots). We’ve implemented a BRT-lite bus network throughout the city and all the main corridors have 15 minute or better combined service pretty much all day long.

I recently visited your city from Indiana and was shocked. I can’t think of any comparable city in America with a transit network even close, especially in a small city. I think of similar sized cities in the Midwest and most wouldn’t even have public transit. It’s very illustrative .

I’m wondering about the effect of gentrification and displacement on ridership. We talk about the rise of “low income suburbs” that are, certainly in California, not well served by transit. So when the transit dependent riders are displaced out of their transit adjacent urban neighborhoods, I think they move further out and ride less. Not sure how much of the decrease can be attributed to this, but no one seems to even bring it up as a possible cause.

Tri-Met has done some work and attributed this exact effect to lower ridership in certain areas of Portland. This article at Transit Center is by the Tri-Met group that did the work. http://transitcenter.org/2017/11/14/in-portland-economic-displacement-may-be-a-driver-of-transit-ridership-loss/

Yes, and that’s showing up in higher car ownership rates and vehicle miles traveled, both in California and in most of the US.

Most foreign-born ride the transit in the US and Canada. In fact, in 2016, there are 7.5 million foreign-born people came to Canada. They represented more than 1 in 5 persons in Canada. This is why ridership supported. In my opinion, ridership is more than just increase a service. Transit culture is an important factor, and I think it’s the missing piece in most cities in the US.

It’s an interesting factor, because the US population is becoming more international and non-European, even in small towns that never had diversity before (or only white/black diversity or white/hispanic). People coming from Europe, Asia, Latin America, or Australia are used to a higher level of transit. In some cases they just adjust and drive, and some of them even see it as a bonus of living in the US. But many others would like to see more transit, or feel burdened because it’s not there. And as their businesses become established and they have children and grandchildren, that gradually influences the attitudes of Americans as a whole. So that will likely soften the roadblocks to better transit.

They don’t keep riding if the service sucks.

I’m curious to see Baltimore’s numbers for the next year, as these predate the launch of BaltimoreLink (they’re the last year of the old system). But I also wonder if MVS is correct that gentrification and displacement might be responsible for large declines, particularly in east coast/midwest cities like Cleveland, Baltimore, Philly, St. Louis, etc.

In Baltimore, for example, while the overall population continues to decline, the city continues to see an influx of young singles and “dinks.” So in outer rowhouse neighborhoods such as Berea, Walbrook, and Sandtown-Winchester, there simply is massive depopulation: when the whole block of rowhouses goes empty, it’s self-evident that that block will no longer be taking the bus!

Meanwhile, other rowhouse neighborhoods are gentrifying, such as Greenmount West, Old Goucher, Highlandtown, Middle East/Eager Park (the “correct” name depends on how long you’ve lived there), even Oliver, but what this means is that you no longer have single-parent households with multiple kids, or large extended families, or carless retirees; now you have young, affluent dinks and singles.

It’s hard to conclude in Baltimore, but in wealthier cities the latter demographic seems predisposed to ubering everywhere, whereas in Baltimore there’s some evidence that at least some young people are inclined to share CityLink tips (the new BaltimoreLink routes) among each other:

https://www.reddit.com/r/baltimore/comments/8cxgtr/commuting_to_fells_point_need_advice/

But still, both abandonment and gentrification mean the density of rowhouse neighborhoods and household size both continue to decline, potentially explaining at least part of the transit ridership decline. Meanwhile, requests for increased service to/on the suburban periphery, especially to various business parks and apartment complexes, continues to grow louder, quickly and sharply!

It would be insightful to include Australasian cities in the comparison. These would be similar to the Canadian cases, but possibly more so.

In Sydney the conservative State government has recently increased the frequency of night and weekend trains from every half hour to every 15-minutes because their 8-car double-deckers were getting overcrowded. The government is also building a new light rail line and a new metro line with 15 km of new tunnels. In Melbourne a new metro line tunnel is under construction, 50 level crossings are being grade separated, and there are several other urban rail extension or amplification projects. Evening trains after 8pm are half hourly with 6-car trains, and have standees until about half way to their suburban terminus. In Perth a new underground rail line is under construction to the airport. All Australasian capital cities have been experiencing strong growth on their urban rail networks, except Perth where there has been a decline in downtown employment following the end of the mining boom, and Brisbane, where inadequate rail staff recruitment led to a decline in reliability.

Unlike US cities, Australasian cities have a full range of services (office, retail, education, entertainment, restaurants, hotels and apartments) in their downtown areas, so they are desirable places to be for purposes in addition to employment. Since downtown parking is expensive, this generates a strong anchor for their public transport networks. The few US cities I have been to recently (Tampa, Atlanta, Huntsville, Los Angeles) the downtown areas were almost exclusively offices and parking with a few restaurants. A weak anchor leads to a weak network.

“The few US cities I have been to recently (Tampa, Atlanta, Huntsville, Los Angeles) the downtown areas were almost exclusively offices and parking with a few restaurants.”

That’s Euclidian zoning at work. it comes from Le Corbusier’s vision of separate districts for residential, retail, theaters, government, industry, etc. While there’s widespread agreement that polluting industries and housing must be kept separate, that doesn’t mean that corner stores and light industry had to be removed from residential neighborhoods. But density caps and Euclidian zoning became established in cities simultaneously and merged into one in people’s minds.

Jarrett has written several times about Australia and said that even though their inner cities may be more traditional, their suburbs and the metros overall are as undense as America, if I understand correctly. I’ve never been to Australia so I don’t know. But I’d be interested in knowing what’s happening in Australia’s suburbs, and whether they also have more transit across the board like Canada does, and whether that shows in higher ridership and support for transit similar to Canada.

Interesting. Here in Montpellier, the south-East where I live is growing quickly, under the french tech pressure, and the next patch that will be built(with currently a handful of houses and a dozen of sheep) will host “1800 flats, 28 000 square meters of offices and commerces, 4700 square meters of public infrastucture”(from the small board they did put over there).

And will be served by the tram stop Pablo Picasso, line 3, which has possible capacity increase(unlike line 1 which is rather overcrowded).

Other interesting thing, the nearby area does not have enough car parks, those are slowly replaced(by public parks who have a secondary use of managing the excess of water in case of flood, a local frequent problem), and the remaiing ones are paying. My own street near the same tram stop has around 70 flats, a reputed primary school with children from the whole city(for the chinese lessons), and 6 small paying car park places as a grand total.

The ideology behind this urbanism seems clear to me : promote the usage of the tramway. Which suits me, up to a point. The countryside is very badly served by buses, and nearly not at all by the tram network. Inviting friends has become a headache. And cars parked in illegal places are always in numbers.

percent changes cover up the total number of riders. in Houston and phoenix I suspect that the starting number of riders is small (especially compared to the percent of trips made by automobile), that any addition of a bus line would result in a sizable percentage ridership increase.

Australian cities are in the middle when it comes to transit.

They are not as good as Canada, but not as bad as the USA. While the share of work trips by transit is similar in the larger cities with the larger cities in Canada. It is the all day transit usage rates which are lower in Australian cities.

Australian cities tend to have pretty good metropolitan rail networks. But where they have failed until recently is suburban bus service. It was not uncommon to have almost no bus services, or very little service on Sundays. Very common to have almost no bus service after 7pm in most suburban areas, and hourly service being the norm.

This has slowly changed in bigger cities like Melbourne, and the ridership has been skyrocketing with each improvement.

The suburbs of Australian cities are just as dense as Canadian ones, minus the high-rises. And in many cases, they have old style downtown retail districts centre on train stations. So they might be a step better than Canadian suburbs.

Overall though, Australian cities are on the right track to improving transit services, and with each improvement ridership has grown.

@Malcolm M

Thanks for the Australian perspective. It sounds like Australian cities are quite similar to Canadian ones (a full range of services & residential downtown, combined with expensive parking.

There is a terrific story in the Seattle Times today comparing the construction of bike lanes in Seattle with those in Vancouver. (https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/transportation/as-seattle-struggles-with-bike-lanes-vancouver-b-c-has-won-the-battle/). There are many parallels in this story with the question of transit ridership brought up here. For the bike lanes at least, there are two over-riding reasons why, in less than ten years, Vancouver has built a great bike system while Seattle continues to create controversy. Those differences come down to two things: 1) aggressive leadership in Vancouver, which pushed staff to get things right, despite early failures; and 2) creating a network, so that one improvement connected to and built on another.

The network effect can never be understated. And is usually the reason why private operators can’t build a decent network – they simply focus on the most juicy axis, and purposefully forget the feeder lines.

I’ve travelled to many US cities and I think it comes down to two things. The first is density – most US cities are actually not very dense when compared to Canadian cities. The suburbs especially are more sprawling, making it more convenient to drive a car everywhere. The second is that there is simply more space for cars in US cities. Accommodation is made for a lot of parking in the city centres. There is a lot in Canada too, but it seems much much higher in the USA.

While Seattle is doing well, I think it could do so much better if it amalgamated all of the various transit systems into a single integrated system. For example, Link Light Rail is run by Sound Transit, so you cannot transfer without paying again to King County bus.

“Accommodation is made for a lot of parking in the city centres.”

That’s a signfiicant point. The reason central Los Angeles is less dense and feels less urban than New York or Chicago is parking minimums. Highrises and lowrises must have parking, and that pushes things apart. Most cities in the US devote *half* their buildable land to streets and parking.

I don’t think you can talk about Vancouver’s success without speaking about the downtown density and the Skytrain system. Since many have spoken about Vancouver’s transit-supportive density, I want to make sure that the Skytrain system is mentioned. Vancouver opened a new line just before the Olympics. A lot of ridership growth is due to this fact. The Skytrain offers two major advantages – speed and frequency.

In most other North American cities the options are light rail running in semi-exclusive traffic or subway (either part of a light or heavy rail system) which comes with astronomical costs. Skytrain predominantly rides on an a grade-separated aerial structural. This allows for automation, which allows for frequency especially off-peak hours and more importantly, speed. While more expensive than a ground-level light rail, it is significantly cheaper than subways. Few American have the density to support subways. In the late 19th / early 20th century it was the El’s not the later-to-come subways that made New York and Chicago and other East Coast Cities transit dependent.

Let’s compare a few other West Coast transit systems:

Los Angeles’ new Expo line between Downtown and Santa Monica takes 50 minutes, at least 20 minutes of this is a direct penalty of some mixed traffic portions. Seattle’s new underground light rail system is fast and extremely popular but costs are exorbitant and only so much will be built in this fashion. Portland’s light rail system is large and slow and follows too many easy but undesirable routes like the median of freeways for its speedy sections.

Yes, Vancouver and Seattle has seen increases on bus routes but this is because the improved rail backbone makes the entire system more robust, useful and builds critical mass throughout the system allowing for increased frequency throughout. The visual impact of aerial guideways will always be an issue. But I just don’t think there is an alternative to providing the kind of transit that would be competitive with the private car at medium densities of North American Cities.

Skytrain’s frequency is because it’s driverless. Anything grade-separated can be driverless. The US has mostly old subways and els and new surface light rail. The underground sections of BART and MARTA are because of density and/or federal funding. The subways in LA are because of density. But 90% of recent American systems are surface light rail, because people want low capital costs. Seattle is unique because it has such steep hills that surface wasn’t feasible in the highest-ridership axis (downtown to Northgate), and running it on the freeway there was deemed unacceptable because it would bypass the high-ridership neighborhoods. And as it was designed, neighborhoods one-by-one said they want grade separation too and were willing to pay for it, so only the oldest phase has substantial surface segments. I believe it’s worth the price because it’s more effective transportation than surface rail. But so far no other city has deviated from the 90-100% surface model, and it’s unclear whether any will. (Germany has a lot of surface light rail, but in most cases it has downtown tunnels.)

Elevated has emerged in Seattle as the default alternative because it’s cheaper than tunnels and people don’t want surface. But the first line requires drivers because it has level crossings, and so far all the other plans have drivers too. So there are no driverless plans yet, and thus no chance for 5-minute frequency at midnight. But in other cities most plans are still surface or along highways, because their paramount concern is low capital costs.

There were other options than a very deep tunnel in Seattle. A bridge could have been built over the Montlake Cut beside an existing bridge, but officials opposed it as did the University of Washington. Some cut-and-cover tunnels could have been used as well, since the line could have then been shallow. While the original intention was to avoid being beside the I 5 freeway, in the end, that is exactly what happened for much of the new construction. Not only is it undesirable for TOD, when the next big earthquake comes both the freeway and transit will be damaged together.

Great points.

American rapid transit systems suffer from too much slow surface LRT segments, and infrequent service. Even in Portland, the frequency on the LRT system is pitiful outside of the core segment.

It is no wonder the ridership is not there in American cities, when people are waiting 20, 30 minutes for a LRT train.

American cities add some transit but they don’t look at it from the perspective of people who take transit full time and don’t have cars. The reason over 50% of people in New York and London don’t have cars is that they can walk out of a building, wait just a few minutes for transit, and it goes everywhere they want to. As one man said in Who Framed Roger Rabbit, “Why would I want to drive on your lousy freeway when I can take the Red Car for a nickel?” If you have that level of transit, why bother with the cost of a car and traffic and finding a parking space? But cities don’t look at what it would take for 50% of the people to not have cars citywide; they just add a little more transit, which makes it a little less convenient, but that’s not the same as making it convenient, or more convenient than cars.

The Canadian cities have simply followed the patterns that have resulted in successful transit in the U. S, while avoiding our failures. There are a couple key concepts:

1) Concentrate on the core. If you look at North American light rail or heavy rail systems (which should be lumped together, but can be found https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_North_American_light_rail_systems_by_ridership and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_North_American_rapid_transit_systems_by_ridership) you can see that none of the Canadian systems are especially long. Dallas, L. A., Philadelphia, Portland and Denver all have longer light rail lines than the longest subways in Canada. Of course cities like New York, Chicago, San Fransisco or Washington D. C. are much bigger.

But it isn’t just that the Canadian lines are relatively short (and too short, in some cases) but they rarely venture outside the urban core. Even in sprawling Calgary, with its relatively large 37 miles of track, just about all of this is within ten miles of the city. Vancouver does serve its suburbs, but most of its system lies within the urban core, even if the trains go outside the city limits (Vancouver proper in square area is fairly small, similar to San Fransisco and D. C.). More to the point, they haven’t neglected the core of the city to serve distant suburbs. In that regard they are like most of the old American systems, and the few huge success stories for modern U. S. systems. The Washington D. C. Metro does go out to serve the suburbs, but it thoroughly covers the areas within a few miles of the center.

In contrast, many American cities have built subways that sprawl to the suburbs, and the result has been disappointing ridership, which in turn leads to poor transit outcomes. SkyTrain has much better ridership per mile than BART, which is amazing given the density and overall population of the two cities, but not at all surprising when you look at the subway maps. BART isn’t alone — DART is worse, as is Denver’s RTD. These systems are not very cost effective — It is very expensive to run a train with no one on it. That leads to cost cutting in other (arguably just as important) parts of the system, or cuts to headways (as was the recent case with Denver). U. S. cities still seem to be going down this failed path — as exemplified by Seattle’s decision to build miles of light rail to distant suburbs (at very high cost), while neglecting to cover their urban core.

2) Don’t forget the buses. In just about all cities (u. S. and Canadian) bus ridership is higher than train ridership. Even cities with model subway systems have very high bus ridership. The Canadian cities tend to follow a model that acknowledges and embraces this. Vancouver is a great example. It has very high rail ridership for a city its size, and even higher bus ridership. The buses complement the trains, as reported here before (http://humantransit.org/2010/02/vancouver-the-almost-perfect-grid.html). What Jarrett Walker didn’t mention is the relative speed of both the trains and the buses. While the train speed is to be expected (since they are grade separated) the buses run fairly fast and very frequently.

The two go together. If your subway system (whether build with light or heavy rail) is focused on the urban core, it will be cost effective. This will allow you to spend money throughout the system on complementary bus service. Someone from the suburbs may have to take a bus to a train to get into town, but once they get there, they be able to get anywhere fairly quickly. It isn’t like the Canadians haven’t made mistakes (Toronto needs to expand their subway, Vancouver should build the UBC line before fussing around with extra lines in Surrey) but by and large they are building systems that are cost effective, which ultimately make very them effective for everyone.

Vancouver is great with bus frequency but pretty poor with bus speed and bus priority. Vancouver really needs to up its bus priority game.

It’s worth noting that Toronto’s ridership stagnation is actually due to overcrowding – it’s physically impossible for more people to fit onboard the subways, streetcars and buses even though there are many people who wish to do so. And that’s not just on downtown subways and streetcars: most suburban arterial bus routes are running as frequently as physically possible (every 2 minutes) but still leaving people standing on the curb. Those ordinary bus routes typically have ridership around 20,000 – 40,000/day, which more than many U.S. light rail lines. Meanwhile the King Streetcar has increased from 65,000 to 80,000/day in the last three years, exceeding many entire U.S. light rail networks. Both of the primary subway lines are over-capacity, with Line 1 (720,000/day) reaching a standing load leaving the very first station (Finch), and reaching a crush load only half way to downtown (Eglinton). Regardless of the transit-friendly urban form, people from midtown to downtown are not able to take transit because the trains are already full with suburbanites.

This is entirely due to politics driving transit investment. Between the 1970s and the 2010s, virtually all transit infrastructure was built for uncongested routes in politically-important outer-suburban areas, leaving the rest of the city bursting at the seams.

That is not the whole story. The old City of Toronto actually advocated for no expansion of rapid transit into the downtown area, in a bid to stop significant development downtown, and to push office development to the suburbs. The idea being the the old victorian neighborhoods would be protected from development.

Luckily, business does not think that way, and after the slump in the 1990s of offices moving to the outer suburbs, downtown is now the place to be again, and the transit is overcrowded. Not building transit does not mean that development will stay away. And we are now paying for this underinvestment in the core of the city, which was partly brought about by political forces trying to stop development in the inner city.

I also think the other (critical) part of the story is the explosion of GO Transit ridership, which if I understand current plans, include basically subway frequencies but on existing tracks like Paris’ RER.

We’ve actually just learnt Toronto had been underreporting it’s ridership by about 30 percent with methodology errors. Don’t have a source present, but it has been recent news and would be Google-able . So Toronto is really doing as well as anyone, if not better .

I had an enlightening experience travelling from my home of Indianapolis to the small Canadian city of Kingston for work.

I was shocked that the city of maybe 175 000 if that had literally better bus service than my metropolis of Indianapolis.

I got around in Kingston with the network of frequent express buses as well as local buses, even though the drive through town would have taken mere minutes from end to end. They also have reloadable smart cards and bus times displayed at some stops.

To me Kingston is the best example of America vs Canada on transit. Compare Kingston’s network to any American city of three or four times the size, and Kingston will easily defeat us. It won’t even be close. I’m sure other smaller Canadians cities (confirmed by my experiences in London Ontario) are the same.

Yeah it’s damn good. I go across the border to Windsor Canada all the time. I live in Plymouth, Michigan. Forget about transit here. But I drink when I’m in Windsor (whiskey city!) So i use the bus.

It picks you up in Detroit, drives you to their central transit terminal, and there are frequent buses througout town. Even getting to the suburbs is very possible, as I once learned.

All in a pretty small city.

If you look at maps, or better still satellite photos, of Canadian and American cities you will see a lot less land in Canadian cities cities wasted on “freeways” and their massive interchanges. In th 1970 Toronto cancelled the Spadina expressway, the Black Creek Expressway, the Eglinton/Scarlett Heights Expressway and the Crosstown Expressway. This saved a lot of Toronto from being changes into “Carmagedon.”

Until Sept. 1963 the TTC ran mainly in the old city where the street cars were met with feeder bus services to the outer ends of the street car lines. The suburban bus service was mainly local radial service to a street car terminal or Eglinton Subway Station. It was almost impossible to go from one part of the suburbs to another on public transit. In 1963 the TTC realigned its suburban service into a true grid. The bus line I ended up taking to University had no service in ’63 but was every 4 minutes during rush hour in ’67. It had at least every 15 minute service in the off peak until 12:30 a.m. then 30 minute until the end of service at 2:00 a.m. It was, and still is, one of the longest bus lines in the city.

Toronto has 10 minute or better service on a large network of surface routes for most of the day and an owl service on major streets of every 1/2 hour. Toronto also has a larger proportion of riders who make a least 1 transfer (connection for Jarrett) than most other cities. I was at a 3 day conference in downtown Toronto and I took GO train, a subway and a street car because it was faster and cheaper than driving and parking in the downtown. (It was 17 miles on GO 2 stops on the subway and 1 on the street car. I would have walked if it hadn’t been there.)

In 2015 Toronto had more high rises under construction than New York, Chicago and L A combined, A lot of it around the downtown or along the waterfront. Most of the former industrial areas along the main lake shore rail line now have medium density residential development under 6 stories but a lot of high rises are following behind them. Why do you think the King Street car went from 64,000 to over 80,000 riders as soon as the transit priority was introduced.

Last fall when I could not drive because of knee surgery I did a similar trip to a suburban hotel except this time the subway ride was 6.5 miles long and the bus trip was 3. I did it off peak but it was 20 minutes faster than the last time I drove there in the rush hour. The Toronto area has very large, mostly interconnected, set of transit systems that makes it possible to live in many areas outside the downtown core and survive nicely without a car. It may take more planning than most people are willing to make but it can be done.

Is Toronto transit heaven? No but it has done quite well considering the neglect bestowed upon it by upper levels of government. It desperately needs a north-south subway line in the east end to intercept riders from the Yonge Street portion of line 1 which is half full when it leaves its norther terminal. Hopefully it will get built next after the crosstown LRT line which will have 12 of its 19 km in a tunnel.