The question of walking distance in transit is much bigger than it seems. A huge range of consequential decisions — including stop spacing, network structure, travel time, reliability standards, frequency and even mode choice — depend on assumptions about how far customers will be willing to walk. The same issue also governs the amount of money an agency will have to spend on predictably low-ridership services that exist purely for social-service or “equity” reasons.

Yesterday I received an email asking about how walking distance standards vary around the world. I don’t know the whole world, but in the countries I’ve worked in (US, Canada, Australia, New Zealand) the view is pretty consistent:

- If you have to choose a single walking distance standard for all situations, the most commonly cited standard is 400m or 1/4 mi. Europe tends to be comfortable with slightly longer distances.

- However, people walk further to faster services. (Rail advocates are more likely to phrase this as “people walk further to rail”.) This doesn’t have to be a sociological or humanistic debate, though urbanists often frame it that way. If you are a rational and informed actor seeking to minimize travel time, it often makes sense to walk more than 400m to a rapid transit station rather than wait for a bus to cover such a short distance.

- Although the common standard is 400m or 1/4 mi, we all know that this cannot possibly be a hard boundary. It makes no sense to assume that if you live 395m from a bus stop you’ll be totally happy to walk that distance while your neighbor, who lives 405m from the same stop, will be totally unwilling to. Obviously, the relationship between distance and willingness to walk is a continuous curve without sharp breaks. This has to be said because our language often forces us to create the illusion of sharp breaks, e.g. when we say something like “people are generally willing to walk up to 400m to transit.”

Finally, it’s remarkably hard to sift data into a form that produces unequivocal guidance on the question. For example, the leading US guide on transit planning, the Transit Capacity and Quality of Service Manual, offers only this:

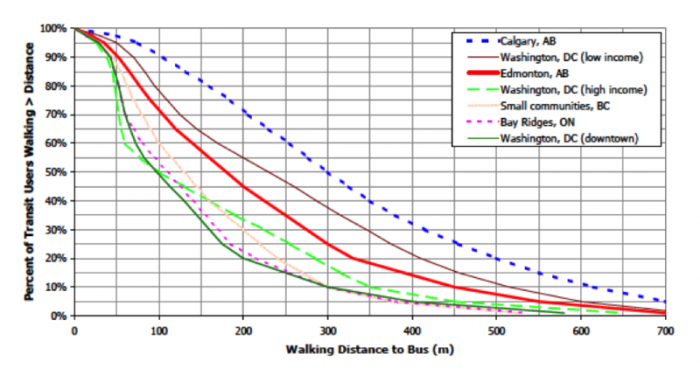

(Source: TCQSM Chapter 3, Appendix A, p. 3-93. Discussion and version in US units is on p. 3-9.)

This survey-based graph shows the breakdown of local bus passengers by the distance they walked to get to the service. As you’d expect, few people walk more than 200m in downtown Washington, DC because in such a densely served area, few people would need to. In low-density Calgary, at the opposite extreme, many people have to walk fairly long distances.

But extrapolating opinions from behavior is a tricky business. It’s hard to reason from how far people walk to how far they’re willing to walk. To do that, you’d have to determine whether each rider would be willing to walk further than he actually has to walk. You’d also have to speculate about each rider’s available options. If 1/10 of Calgary’s bus riders walk 600m or more, does that mean they’re willing to? Or does it mean that these people are so lacking in good alternatives that they feel forced to walk that far? (The difference between “high income” and “low income” Washington DC suggests that range of options does have something to do with it.) Sociologists and demographers can have a field day parsing this question, but they’re unlikely to come up with an answer of such statistical certainty that it definitively sweeps the question aside.

So we approximate. We generally assume that 400m is a rough upper bound for slow local-stop service, and that for rapid-transit (usually rail) we can expect people to walk up to 1000m or so.

But when we try to apply these rules of thumb, we hit another hard issue (or at least we do if we’re willing to acknowledge it). Are we talking about true walking distance, or just air distance? Over and over, in transit studies, you’ll see circles around bus stops being used to indicate the potential market area, as though everyone within 400m air distance is within 400m walk distance.

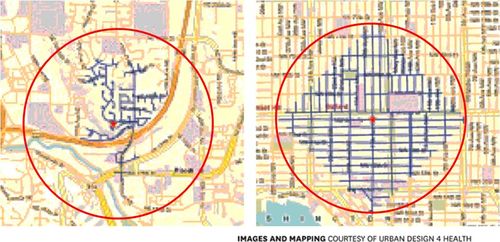

Remember this graphic?

In both images, the red dot is a transit stop and the red circle is an air-distance radius. If you draw 400m circles around stops based on the assumption of a 400m walking distance, you’re implying that the whole circle is within walking distance. In fact, even with the near-perfect pedestrian grid in the right-hand image, the area within 400m walk (outline in blue) is only 64% of the red air-distance circle. With an obstructed suburban network like the left-hand image, it can be less than 30%.

Obviously, the market area around each stop should really be defined by the walkable area, which requires a knowledge of the local pedestrian network. That requires a complete GIS database of every walkable link in the community — an extremely detailed task that few jurisdictions have been willing to attempt until recently. Even in Canberra, Australia, which is known in the business for the extreme richness of off-street pedestrian connections, no reliable database of them was available for modelling purposes as recently as last year.

Still, if you don’t have such a database, it should be easy to adjust the walking distance standard to reflect the problem. If you know you have a good street grid, then you can just adjust the radius to reflect the area within 400m walk. In the right-hand image above, do the math and you’ll figure out that if the radius of the red circle is 400m, then a circle whose area is the same as that of the blue diamond — the actual area in walking distance — would have a radius of 319m. So if you want to roughly model the actual radius that arises from a 400m walking distance, and you have a well-connected street grid, draw a circle 319m in radius. That doesn’t give you the correct boundaries of the area — it’s a circle rather than a square — but it’s a far better approximation than just drawing a 400m circle. I have never actually seen this done, and I’m not sure why.

One reason might be that secretly, we transit planners all want people to walk further. After all, most transit planners don’t want to just passively respond to current behavior. If they did, they’d all be highway engineers. Most transit planners believe in the importance of shifting behavior in more sustainable directions, and see both transit ridership and walking as deserving encouragement through intervention. They are also aware of the public health benefits of walking.

But we have a more vivid motive to encourage walking. The nature of the transit product is such that if we could stop less often, assuming longer walk distances, we could achieve both better running times and reduced operating cost; the latter could be reinvested as higher frequency. So the two most fundamental determinants of transit travel time — running time and frequency — both depend on our assumption about walking distance.

With such basic things at stake, it’s understandable that planners are always looking for ways to push walking distance wider. That may be the real reason that generations of planners have chosen to approximate a 400m walk with a 400m circle, even though every pedestrian knows how absurd that is.

I prefer to just have the argument in simpler terms. In Canberra, we pushed the walking distance standard from 400m to 500m, not because people were calling us demanding to walk further, but rather because we looked at how much more frequency and speed we would achieve, and the ridership that could attract, and decided that 100m of radius was a small price to pay for such benefits. It comes back to that graph near the top of this post, showing how far people walk to transit in different cities. There’s no definitive authority for a 400m standard as opposed to 300m or 500m or even 600m. Yes, if you pick a bigger radius you’ll lose riders from the outer edges of the radius, but on the other hand, you may buy so much travel time and frequency that your ridership goes up. As with everying else in transit, it depends on what you’re trying to do.

I may have missed it, but did you mention the safety and pleasantness of the walk? That’s definitely a factor for me.

Cap'n. You bet it is. But on the corridor or citywide scale that transit investment planning occurs, it's very hard to quantify that in a defensible way.

“…most transit planners don’t want to just passively respond to current behavior. If they did, they’d all be highway engineers.”

Nice jab! 😀

I’ve gotta say it’s pretty depressing that 400m is generally taken as the distance people are willing to walk. On my daily commute of many years I walked about 1700m to the Skytrain station and back each day. I could have taken the bus, and sometimes I did during inclement weather. But I enjoyed the walk, and I considered it the healthy thing to do.

I think it would be really interesting to compare the acceptable walking distance of people who live in a walkable community (and who are therefore used to walking) with that of people living in a cul-de-sac suburb. I’d be willing to be that the latter would have a lot lower tolerance for walking.

The cruel irony, of course, is that if this is true then the people who want to walk the least are in a situation where they’d have to walk the most to travel via anything other than their car.

Ha, another grid related comment:

If your transit stop is at the center of a 8 or even 10 way intersection of roads radiating out (see Paris), then you can probably get the almost the circle. And along the diagonals, people would have to walk about a third less to reach to cover the same point to point distance.

What about walking distance to transfer?

As an extension to this great piece, I’d be curious where the crossover point is between driving to a park-and-ride station and simply driving to the destination. The question of park-and-ride comes up frequently in meetings surrounding L.A. planned “Subway to the Sea,” but I have my doubts that people will be willing to drive much more than, say, two or three miles to the subway when their destination is just ten miles distant.

@In Brisbane. We aggressively try to minimize walks to transfer.

150m is the high end in my view. Beyond that you need moving walkways

@Jarret> Sorry to digress…

The Tube definitely has a lot of connections that are longer than 150m. But they’re totally under cover in tunnels which connect directly. Most people seem happy with this.

By contrast there’s only about 150m between South Brisbane bus and train stations in Brisbane but given the number of stairs, roads and general annoyances in the crossing it takes longer and is less safe than the much longer transfers in The Tube.

Which does relate to the idea of localised walking patterns. I bet people will walk further through a nice park than they will down a highway. And modern technology (on systems with electronic boarding) could give you some measure of this.

@Tim: New York has a few longer-than-150-meter transfers (51st-53rd/Lex, 14th/6th-7th, 42nd/7th-8th), and those are avoided by anyone who has a better option.

@Jarrett: is there a simple way to estimate how much time you lose from making an extra stop, under various assumptions such as curb lane vs. median stop and on- vs. off-board fare collection?

I have run into analysis situations like this before. After factoring in psychological bias, demographic trends, purchasing behavior, opportunity costs, and incentives, you end up with an answer that is so complex that it isn’t even worth mentioning to anybody. And then everything changes the next month and your analysis is worthless again.

And of course, everybody out there has a theory backed by their own expertise as a human being. And everybody is qualified to say what makes them choose one or another usage pattern. Unfortunately, we tend to extrapolate our own preferences onto others, even though we rarely actually have the same preferences as others.

Randomized controlled trials will work wonders, but for that to happen, people have to be open to the possibility that their favorite theory is wrong. Unfortunately people rarely do things like that…and when they do accept that their theory is wrong, they only do it implicitly after being forced into accepting some other theory by competitive pressure. Its a sad state of affairs.

With some walk connections aligned in a more direct path to the stop, I can imagine the suburban network on the left hand side image could begin to gain a sizeable amount of coverage within the air distance radius. With enough such paths, it could overtake the grid, because of the power of radially aligned paths.

That’s something I noticed about L’Enfant’s radial avenues in DC. They provide diagonal “shortcuts” in the grid network, allowing many of DC’s stop area pedsheds to provide reachable coverage beyond the grid diamond… so DC’s pedsheds actually begin to approximate the air radius circle.

BUT, that’s only if you put the stop at a convergence point of radial streets in the network (as at Dupont Circle). If you don’t place the stop at a convergence area, the opposite happens, and sizeable gaps in the grid diamond suddenly appear.

One important point: The size and orientation of the grid matters. What’s important is the LENGTH of street or walk paths in the coverage area, which is what increases access to uses.

When I visited Santiago, chile, we lived in Las Condes, a faily affluent area in the eastern part of the city. When we went into Santiago, we walked 25 minutes (abour 2,500 metres) to an end of the line Metro Station, even though buses stopped outside our building.

Why?

Because we knew that the Metro would be frequent. That was an assumption, but a correct assumption as trains ran in all time periods every 2 minutes. The bus, we had no idea when it would come by. I knew from asking that it went north to where we could then connect to a regional bus that would take us to Santiago.

Interestingly, we had no issues walking 25 minutes to a metro station, but we never even thought to walk the 15 minutes to the regional bus stop, nor to bother waiting for the local bus.

It seems we’re conditioned to think of rail as fast, reliable and frequent and buses as none of those. For me, I think it is partly the fact that metro lines are always shown on maps, stations are easy to identify and maps of the lines are published and made easily available. Rarely do you see such information for bus lines, even if the lines are frequent and express.

But thinking back, I think part of our decision to walk 25 minutes to the metro line is we knew what to expect. In a country where we don’t speak the language, we knew there would be easy to use maps, ticket machines and ticket counters, easy wayfinding and lots of people (inducing a feeling of safety and security).

@David M. Was this before or after the January 2007 reform of the bus system? J

@Alon. You asked “is there a simple way to estimate how much time you lose from making an extra stop, under various assumptions such as curb lane vs. median stop and on- vs. off-board fare collection?”

As your question anticipates, there are too many variables for such a rule to be clean.

For example, on a busy street with lots of traffic signals, it depends a lot on the signal progression. Car-oriented “green wave” patterns often mean that every time the bus stops for 15-30 seconds, it drops back an entire signal cycle. On the other hand, a transit-preferential signal timing would be keyed to the stopping pattern. The Los Angeles Metro Rapid, for example, is able to achieve a lot with relatively mild signal priority because its stop spacing is so wide (800-1000m as a rule).

Another variable is pullouts vs bulbs. If you’re in mixed traffic and have to pull out of the lane to stop, you face the delay of merging back into the traffic lane. The classic “bulb” or “curb extension” eliminates this problem by allowing you to block the traffic lane while stopped — obviously not a universally loved solution.

Given a specific set of circumstances on a specific street segment, it’s not to hard to figure out the impact of stop spacing. Sometimes you just go out with a bus and experiment to make sure you understand all the factors at play. But there’s no easy rule for delay per stop.

@David M: Bus-based systems occasionally rise to that level of legibility. I used the trolleybus-based rapid transit system when visiting Quito, as the enclosed and staffed high-platform stations, overhead wires, and easily-available maps meant I knew what to expect. But in the US bus-based systems tend to be a complete joke by this standard; only the LA Orange Line seems to have a legibility and amenity level anywhere near that normally associated with rail.

On the other hand, if you think a line showing up on a metro map means you can know what to expect, try showing up at station on the Waterfront section of of the Cleveland Blue/Green lines. These show up on RTA’s maps just like any other metro station, but only have service on weekends!

In Calgary I do believe the policy is to have all residences within 400m of a regular service bus stop. What would skew the numbers would be express (direct to downtown) routes in communities without good feeder service to LRT, BRT light routes, and LRT where walkers walk much further.

a good but older study is here: http://www.enhancements.org/download/trb/1538-003.PDF

There is also a newer study Calgary Transit did on walk up LRT access in the last half decade, but they seem to have removed it from their site.

Cap’n Transit is right on. Distance should be second to quality of the walk.

You can be in a “beautiful” (in terms of upkeep) suburb, but the walk feels exhausting because humans are not comfortable walking in such open spaces. The monotony of the homes doesn’t help. It’s boring. Blocks simply feel endless.

In a city, the distance might be longer, but the walk feels shorter because you have more to look at. Also, the streetwall makes us feel safer for evolutionary reasons. On the other hand…we dont want to walk directly adjacent to a wall.

Barriers also make a huge impact. A bus stop might be 100m away, but if you have to cross a river with very high winds….you just wont do it. Especially if the sidealk is 3ft wide and traffic is moving at 60mph.

Or how about a highway? Modern highways are designed so that the onramps are essentially part of the freeway. There may be a crosswalk, but any car foolish enough to stop for the epdestrian WILL be hit from behind. So just walking 100m, past an on and on offramp may be enough to say “forget about it” .

And that’s not even getting into the whole crime/safety bit of a neighborhood, just the built up angle.

This may be hard to quantify, but someone should find out how, because it’s a huge part of deciding how and when people will walk.

JJJJ and Cap'n. These considerations will start to affect planning when cities figure out how to include these features of experience in their transport models. Some of what you describe is not hard to quantify, but of course it tends to be described as an aesthetic reaction, and the aesthetic, by definition, is impossible to model.

Yes, people are willing to walk further for faster (and I think more frequent) service, and asking them to do so allows more and better service to be provided.

But I have some qualms. If we’re talking about commute trips, that’s one thing. But most trips are not commute trips. A lot of transit users are elderly or too young to drive. Older and younger riders may be dependent on transit, but not as free to walk a long distance. If walk distances are too long for older folks, they’ll be shunted to far more expensive paratransit alternatives. I read a lot of online comments about how we should all bike and walk farther, and I get the impression sometimes that only young and single people are in the room. So there’s got to be some balance — or, there needs to be a different standard for local access routes than for express or BRT routes.

I agree that people will travel farther to transit within connected street networks than disconnected ones, and perhaps a different distance standard should be used to reflect the difficulty in traversing a straight line when there is none. I’d add that grades can present the same type of practical impediment, and that access distances should be shorter as grades get steeper.

Instead of a fixed spatial distance, one should more use a temporal distance. Those 400 m can be easily translated into 5 minutes.

In fact, that may give a more reliable estimate for potential users, as it takes account of obstacles like highways with low-priority traffic lights for pedestrians.

And, of course, service density has a very big influence; what’s the use of having a bus stop in front of your front door, but you see only a few buses per day, whereas in 7 minutes you reach a stop (bus or rail) having 15 minute intervals (or even denser services).

@Max Wyss, you’re still measuring a distance even if it were time. Slower pedestrians will cover less distance with the same time.

Six of one …

@Max Wyss. Agreed, provided you assume an average walk speed (eg 5km/h).

Assuming it’s not a turn up & go frequent service and you need to be at the stop/station at a particular time your time calculations need to factor in worst case scenarios for things like traffic light cycles.

Two 2-min cycles already adds 4min without any waiting time. Even worse is a busy road with no lights (or just a roundabout) due to the constant stream of traffic (regarded as perfect efficiency by the road engineer) the maximum wait is indeterminate. Whereas with a zebra crossing it’s near enough to zero and only walking time need be considered.

If you wanted to convert waiting time at intersections to distance you could have walked in the time you were waiting it’s about 100 metres per 1 minute. So if you need to pass 3 crossings @ 90 sec cycles, that’s 4.5 minutes or the time equivalent of over 400 metres. You’ve blown the pedshed budget without having walked a single metre.

A focus on time is also healthy because it sharpens the mind by encouraging thought of end-to-end travel speeds. That’s the thing that matters – more so than distance.

Only a tiny proportion of buildings can be reached within 5 min walk of a station’s fare barriers or a bus stop. I think 10 min is a more workable figure to use for planning purposes (for local buses) and maybe 15 min for rapid transit (though where services involve transfers even walks up to 20 min compare favourably with transferring).

The type of crossings makes a difference to pedestrian walktime/quality. The wrong combination of interesection spacing and walk-speed can mean the pedestrian will hit a “red wave”.

There’s also motorists attitudes… in both Alberta and Ontario, pedestrians have right-of-way at crosswalks (unless there’s a “don’t sign” illuminated). In Alberta, a motorist who enters a crosswalk which is occupied by a pedestrian can be fined $500 on-the-spot. Ontario doesn’t have anything like that, and I found that makes a big difference to how motorists approach corsswalks.

@Sean, I think the real irony may come from the fact that those in sprawl areas may tolerate the extra distance to transit because they realize that it cannot stop at their door, and thus have to walk further to get to it.

With that said, besides the divide between choice riders and transit dependent, other “hooks” may be required to encourage the walk (paid parking, fast service, etc.).

The use of a time-based scale and methods for “reductions” based on difficult intersections or uncomfortable surroundings sound appropriate, if just as hard to measure as the new “multimodal level of service” for roadways. Ultimately, it does take some judgement on the walking environment from the planner or engineer.

While working on a rapid transit station characteristics research project, I also came across the issue of where do you measure the “station point.” Does a person walk a little farther if the last minute is riding the escalator to the train platform because it feels like they’ve already reached the service, and what if there are two different entrances at either end of the platform? These small differences can actually have a huge effect. I used to position myself at the proper end of the train when riding the U-Bahn in Munich so that I would be nearest the side of the platform that exited toward my destination–this could cut at least half a minute from my travel time, depending on escalator congestion.

I live in the DC/Metro area and recently moved from an apartment that had a shorter but less pleasant walk to the metro rail to one that is a longer/more pleasant walk to the train. I think that if the area you are walking through is active and “alive”, you’re more likely to be willing to walk further distances.

Acceptable distance is mediated by ease/comfort level of the route(flat v hilly, crime), what one might be carrying (full back pack of tools or groceries), and the time advantage of the mode one will use. I live 12min walk from a BART station, but 2-4 from a “Rapid” bus stop(w/Nextbus prediction). The door to door to downtown Oakland or Berkeley is about equal. OTOH for SF and other distant points, BART is the only realistic choice.

In Japan, housing ads in major cities usually say how far they are from the train stop. They specify this in terms of how many minutes it takes to walk to the station entrance. I can’t remember precisely what the formula is, but there is some ratio between meters and minutes that everyone uses.

The funny thing was, the place where I lived in Tokyo was technically a 2 minute walk from Shinjuku station (and was advertised as such), but the station is so massive that depending on what line I wanted to take, it could be a 30 minute walk to the actual platform.

The length of a subway train is around 170m. If you board on the far end of the train, walk around the platform and getting connected to another line some distance away. You could have walked a few hundred meters within the paid area. Yet this is perceived as a single station by by the passenger. The map maker help project this perception by making it a big dot on the map.

The Central station in Hong Kong, the busiest station in one of the busiest subway, is connected to the Hong Kong station via a board tunnel. Depends on which end of the train you have boarded, it can be 600m or more to walk from one platform to another platform.

http://dl.dropbox.com/u/12840293/tmp/hk_mtr_central.png

This is probably for masochistic statistics only, I measured 2km between the far end of 2 terminals in the Heathrow airport. Not sure if there is connected walkway between the buildings though.

It seems to me both of these situations (What exactly is the area serviced by a 400M walk from a particular location? How far will people walk to local or rapid transit?) are ideal candidates for a kind of ‘reverse engineering’ (sort of).

1) I would imagine pretty much any university engineering &/or IT dept could find a student to write you a GPS app to ‘walk’ 400M in every direction using roads/walkways, etc.. from a particular spot, and then draw a circular circumference (or elipsis, etc…) around it. I think the “we can’t tell how far 400M walking distance really is” argument may be another way to obscure the issue in order to ‘push’ the distance.

2) I wonder if (m)any studies have been done documenting exactly how far people DO walk to existing rapid or local transit stops and at what rate acceptable walking distance falls off, and then categorizing the factors (commuter identified or otherwise) that were cited. If the categorization was done with enough attention to detail (e.g. things like the ‘quality’ of the walking experience others have mentioned) such that it was repeatable, I would think it wouldn’t be that difficult to come up a type of formula one could apply to new situations. It could also potentially be used to ‘improve’ situations around current stops/stations in order to maximize walk-ins.

Lastly, I think it’s important to differentiate between walking distance to transit – say for urban walkable communities – and biking or driving distance to further flung suburban stations with bike/scooter/car parking facilities. The further one gets from the core, the less frequent and less available transit becomes. That isn’t necessarily a problem, unless there is some ideological restriction that says that EVERYONE must walk to transit or thhhhbbbt. With adequate parking, one stop can service a large suburban area that might not otherwise take transit. I can’t see how that is a bad thing.

Sorry, that should be ‘ellipse’, not elipsis. That should teach me not to comment and cook, etc… at the same time. But it probably won’t.

@Anne, never mind elipsis, what’s “thhhhbbbt”?

Anyway, my current focus is buses in Abu Dhabi. Forecast max temp today 102F, and it’s only spring. Evenings cooler with luck, but more humid. Who would like to walk 700m /yds in that heat. (What’s all these metres doing on a mainly ‘merkin blog?). And development densities are low. AND we are trying to attract to transit “choice riders” (target mode share to transit in 2030 is 40%!)

How on earth do you cope with that? The Urban Planners are targeting 5 mins/300m (you walk slow when it’s hot). We [transit people] have ended up recommending 500m stop spacing, with routes ideally 1km apart – [idealised] this would only put 35% of the ground area within 300m of a stop, allowing for the catchment being a diamond, not a circle. Thankfully, current development is concentrated along the block perimeters, but even then it’s a bit of a cop-out. We are also recommending more “diagonal footways”.

But this factor of highway crossings, already mentioned, is also a major factor. Most bus roads in Abu Dhabi are 4+4 or more divided highways with a median barrier (in which peds have engineered gaps!). There’s a mid-block ped subway if you are lucky. So even in downtown, where bus routes are 500m or less apart and stops every 300m or so, many front doors are >300m from a stop on the far side of the highway.

(PS: Thanks, Jarrett, for returning to my favourite theme!)

I wouldn’t call this a “‘merkin” blog, nor an American one for that matter. 🙂 While Jarrett is a US citizen by birth, his current home is in Vancouver BC and his prior haunts were in Sydney. There’s nothing US-specific about this site. (US transit projects and systems are sometimes the focus of articles, but so are projects and systems elsewhere).

But, yes, weather can affect typical walking distance. It also affects tolerable waiting times–as someone who lives in the US Pacific Northwest, I can assure you that waiting for a bus on the side of the road in an Oregon rainstorm sucks. Likewise for standing on the curb in the middle east, or in Helsinki in the winter.

A better way to cope with nasty weather is not to decrease stop spacing (which reduces service speed and throughput, which can then lead to reductions in frequency, which then lead to more time spent by patrons in the aforementioned nasty weather); but to improve the pedestrian environment. Bus shelters can provide shade and cover from the elements; protected pedestrian walkways can provide both safety and shelter.

@Alan Howes,

“thhhhbbbt” was my poor attempt to write a ‘raspberry’, also known in the U.S. as a ‘Bronx Cheer’.

I believe the correct spelling I was looking for was “thbpbpthpt”: http://drawn.ca/archive/thbpbpthpt/

@EngineerScotty Bus shelters definately improve the expericne of waiting at a stop, but not the experience of walking to the stop.

Further, how many bus-based transit agencies have (or aim to have) shelters at every stop?

Endlessly debated, never resolved. People will walk as far as they have to when they have no other choice. Those with choice tend to be quite selective. Convenience at both ends (commute and park) have to compete. I have before me a complaint that somebody cannot park within 150m of their home. Will never convince that person that 400m to a bus is a better option! When I was working on rapid bus transit we assumed a 400m radius, but found in follow-up surveys that people walked 1000m to it to access 10 min frequency, in preference to less frequent (2 per hour) bus services within 200m of their homes. One issue that is missing is information. Unless you know your local service, or how to find out, it can be impossible to find the nearest bus stop and actually understand where the bus that stops there goes (in Sydney). There is such a dearth of information that even an old transport planner like me sometimes can’t work it out. And with 192 routes in the city centre it can be quite confusing both in and out.

One thing that is very important about walking (or human-powered transport in general) that you are much more in control of how long your trip is going to take, than in any motor vehicle.

If you are walking and find yourself running late, you can walk faster, or run. It you see a light up ahead, you can run a short distance to make it. Or, you can change the order in which you cross various streets so you always make progress, not matter what the signal phase is when you get to the intersection. Or, if you don’t want to get up early enough to walk or run, you can ride a bike and get where to need to go with about the same speed as a local bus, but a reliability that a local bus, or even a taxi, will never match.

In other words, when you walk or bike somewhere, you don’t need to allow a bunch of “pad” time in your schedule for things like bad traffic, missed lights, waiting for a late bus, wheelchairs getting on and off, etc. You simply allow the exact amount of time it takes to get where you need to go and unless you slip and fall or something, you can depend on always getting there on time.

To put a concrete example on this, sometimes a transit trip planner will suggest riding a local bus for 1-2 km, then transferring to an express that goes where I need to go. Even though the local bus will probably move faster than a pedestrian, by the time I allow for contingencies like the bus being late, or a wheelchair getting on or off, I’ve allowed practically enough time to simply walk to the express stop, so I figure I may as well just walk. That way, I’m getting exercise and have one less thing to worry about that might go wrong.

On the rare occasions I’m making such trips burdened with lots of stuff to carry, I will consider a bike trailer, a big backpack, a stroller, or possibly even a taxi (for short trips, the cost isn’t that bad), but the local bus will almost never be an option anytime I really need to be somewhere at a particular time.

Great discussion. @EngScotty, @TomWest – OK, sheltered walkways can be effective against rain or wind – but for heat & humidity? Can anyone point me at good examples? Just shading from the sun is useful, but not enough (believe me, I walk around a lot in the Gulf. And change a lot of shirts.). The most practicable solution is to move the walking inside the buildings – OK perhaps in downtown, but difficult elsewhere, where any sort of provision is going to be expensive per rider.

(Pacé Jarrett, about 60% of HT hits are from US. Which accounts for my surprise to find NO-ONE posting in feet or yards. We in the UK are totally confused about metrication!)

In the Helsinki region we usually use a rough multiplier of 1.3 for converting air distance to real walking distance. Rounding to the nearest 50 m you get 300/400, 400/500, 500/650 and 600/800. This tends to work quite well in environments without large barriers like motorways or rivers.

For walking speed I use 1.2 m/s as this is used in our journey planner and for traffic light engineering. 5.5, 7, 9 and 11 minutes respectively for the above distances.

Our new service quality standards include recommended and maximum walking distances to normal or trunk services for each service category in addition to service frequencies. Trunk lines are allowed longer walking distances.

@Alan. My sense is that at least for people who like numbers, it's a mark of coolness among young US adults to be conversant in Metric. It's an understandable effect of the convergence of (a) the intrinsic hassle of Imperial units, (b) the unprecedented degree of international conversation made possible by the internet, and (c) the inevitable need to rebel against their parents generation (or to "kill the father" as Freud so delicately put it)

@ Alan – I think that’s an intelligent way of saying that metric units are better. Metric units are also understood by more people – which tends to increase the usefulness of anything (think of this as social economies of scale if you like). In much the same way that the large numbers of people who speak English (at least as a second language) has made it into the default international language, metric units are the default technical language (assuming that you want to be understood by as many people as possible).

@ Lauri – while those conversion ratios are a good first approximation, they don’t really solve the issue highlighted by the images in Jarrett’s post. That is, they do not reflect the geometry of the street network, which can have major impacts on access to bus stops.

I’d add that those of us who are trained as scientists or engineers do much of our business in SI, so its now big deal. Here, I generally use SI, given the significant international participation–on Portland Transport, a Portland-OR focused transport blog where I’m a contributing editor, I generally use feet and miles.

But yes, some of it’s cultural–much of the opposition to SI in the US (as well as the opposition to many other useful social policies, such as transit itself) springs forth from the nexus of a politically-powerful business community whose interests are threatened by the proposed change, and a rather xenophobic subset of the population which will oppose anything that they think is foreign–especially if, like SI, its origin is French. 🙂 Yet despite this, much commerce in the US is conducted in metric units–the most common sizes of sodapop containers are 12oz cans and 1l or 2l bottles (go figure), and most Southern good-old-boys have yet to figure out that their fifth of whiskey isn’t really a fifth anymore, and that they’ve been shorted 7ml… 🙂

Hong Kong is mostly metrics. But it takes as long as my childhood for the society to slowly adopt the metric system. When I moved to the US, I am shocked to see the prevalence of imperial system and the use of fractional number. One of the most widely circulated coin has a valuation of 1/4 dollar?? Which of this is longer, 3/8 inch or 5/16 inch? And by how much? I try hardest to resist and reject it on the intellectual ground.

The engineering solution is to consistently use a standard unit internally (metric obviously), and only convert it to non-standard unit when it is needed to communicate with people who don’t understand or have different culture.

A word about metric v inch/foot. I don’t care what nomenclature is used, as long as the screws on the new light switch are threaded to perfectly fit the existing electrical box in the building. (my trade)

A quarter dollar in the US fills the same function as the HK$2 coin in Hong Kong. Our currency is just scaled differently. (The developed country that blows me away in this regard is S. Korea, where prices are generally expressed in thousands of won–here in the US, there are frequent calls to get rid of the penny…)

Re: Pleasantness

“Cap’n. You bet it is. But on the corridor or citywide scale that transit investment planning occurs, it’s very hard to quantify that in a defensible way.”

The starting of a criteria to quantify this for me would be the caliper of street trees and surrounding trees (or canopy coverage) and width of the sidewalk compared to the width of the street.

Re : Metric vs. English

The reality is that the U.S. has been metric underneath since the 1960’s. The switch was made initially for scientific reasons (I was taught the metric system in a grade school science class) and then later for commercial reasons. Many things like rulers, measuring cups, and food containers are dual labeled [e.g. “NET WT 15 OZ (425g) on a can of chili].

My fascination with the topic is tied to [a] the British vs. the French antipathy and how it’s carried over into measurement systems; [b] the oddball units (cubit, hand, stone, etc.) and how they continue to survive; and [c] the quirks and glitches of measuring (conversion errors, repeating decimals in binary, etc.). Personally, while the metric system has its uses (1cc [aka 1ml] of H2O at std. temp. masses 1g), I think the English system is more fun.

@EngineerScotty,

The issue I have with quarter dollar is that in daily life, we often have to combine smaller coins into bigger value. It is faster to compute if they have the value are of 1, 5, 10s, etc.

Say if we want to come up with $8.5, most people can instantly figure out it is $2 + $2 + $2 + $2 + 50c, or $5 + $2 + $1 + 50c. It takes me a little while to learn how to do it with quarter (quick!), e.g. 85c = 25c + 25c + 25c + 10c.

This isn’t too hard to learn of course, especially if you have to deal with it on daily basis. Sizing a fractional number like 5/16 still confounds me.

@Stuart Donovan

True, although we don’t really do winding cul-de-sacs here. Most of our street networks are pretty connected. We are just starting to get suitable data for proper GIS evaluation and this is certainly the way forward. At work our GIS people have promised a tool this summer.

I’m certainly with everyone talking about the quality of walking environments. I would also argue a lot for the (perceived) reliability of the service. I claim people will walk further to good services, which need to be both fast and reliable. Reliability is mostly about punctuality, but also about any service cancellations.

@ Ted K, I should add that while as a tradesperson I have need of US standard screws et al, that never prevented me from mixing a liter of film developer or taking advantage of the extra volume in a liter film tank for a 5th 35mm reel. As to the origin of the metric system, I enjoy reading in French.

Now back to transit dimensions.

400 plus size yards may well be a decent distance for many of us, but nearing 67, I am surely looking forward to knee and ultimately hip issues.

Those of us born here learn to deal with quarters quite quickly–probably the biggest issues with US currency is that we mainly use notes and not coins for US$1 (Hong Kong has a similar issue, in that the closest equivalent denomination–HK$10, is available in both paper and metal forms; though the HK$10 coins seem to be more commonplace than US$1 coins are). That, and the notes all look alike–multicolored notes like HK has are more convenient.

A major problem with focusing too much on walking distance to transit is that when a transit agency has a limited budget, adding more routes to decrease the walking distance results in lower frequencies on each route. Bus routes with lousy frequencies (generally less than every 15 minutes or so) tend to have low ridership. On the other hand many people are willing to walk 1km to a frequent bus route or train line. This may not be true for people with disabilities but in larger cities most users of transit are able bodied. In my city Toronto transit is not well suited for people with disabilities due to overcrowding and broken elevators in subway stations, so disabled people usually use Wheel-Trans. It is probably better for most people to live 1km from a bus stop with a bus every 10 minutes than to live 400m from a bus stop with a bus every 30 minutes.

I’d like to see a quantitative study done to assess the difference between distances people are willing to travel depending on environmental attractiveness/interestingness, e.g. accross and along a spaghetti intersection, vs. down an interesting and safe main street, vs. through suburbia

In some Argentine towns, the buses stopped at every corner, and in others it was every other corner, usually with no signage in either case. More stops doesn’t mean more stopping, though, if passengers are mostly getting on or off one or two at a time. The same passengers get off using the same number of stops, but closer to where they want. In the U.S., every stop is an important, fixed entity with its own sign, separated from one another as much as allowable.

John. Just to be clear, on buses where/when passenger volumes are low, it doesn't matter much because you won't stop at every stop. But it matters a lot as ridership grows.

In certain rural areas (such as “Indian” reservations in the US), people have been known to walk many miles to catch a (very infrequent) bus…

All I want to add to this discussion is “wow, it’s great to see so many smart people working scientifically to solve urban transit issues.” Keep up the good work. My own two bits on the walking distance: I will walk much further based on an impossible-to-quantify combination of aesthetic appeal of walk, weather conditions, my mood, my time-constraints, time I would have to wait for transit, the absence of nasty barriers like highways, and more. Some of this can be quantified but good luck modeling the whole shebang.

Just re-reading this old post and had an insight on this part:

This assumption is the source of a lot of our problems here in the States, because when I read that, I am NOT thinking “I’m deciding between a bus and a walk when the rail station is >400m away”; I’m thinking “I’m going to drive all the way to work if the rail station is that far away”.

Sure enough we have the same issue right now in Austin – where connecting shuttles were dropped from the ‘downtown’ commuter rail station. The transit agency is framing this as “people preferred to walk”, when what actually happened is that almost everybody whose destination was further than a short walk from the rail station is still driving all the way to work.

Question:

Do we have a benchmark from any reliable sources on the normal and comfortable walking distances for people aged between 15 to 65?