Should proposed public transit infrastructure in the US be judged on whether it helps people go places so that they can do things? The US Federal Transit Administration (FTA) is asking this question right now.

FTA helps fund most major transit construct ion projects in the US. Recently, these programs have doled out about $2.3 billion per year in capital funding for transit projects across the country. The Senate Infrastructure Bill would nearly double the annual funding for these programs for the next five years. If there’s a piece of transit infrastructure you want to see, or one that you oppose, you should care about how the FTA makes its funding decisions.

ion projects in the US. Recently, these programs have doled out about $2.3 billion per year in capital funding for transit projects across the country. The Senate Infrastructure Bill would nearly double the annual funding for these programs for the next five years. If there’s a piece of transit infrastructure you want to see, or one that you oppose, you should care about how the FTA makes its funding decisions.

Congress has defined the criteria that FTA must use to evaluate the projects. But the FTA has broad discretion in deciding how to define the measures for each criterion. So now they are asking you, me, and everyone about how we ought to change or update those measures.

Their questions should make us optimistic about what US transit funding could become. They don’t sound like an ancient bureaucracy going through the motions of public consultation. Instead, the agency really seems to want our opinion about how they should measure the success of their investments, a decision that will directly determine what gets funded and built. Read the questions yourself if you don’t believe me.

Does it matter if we can go places, so that we can do things?

FTA asks many good questions, but one especially stands out.

Should FTA consider ‘‘access to opportunity’’ under the Land Use criterion? If so, how specifically could FTA measure it? For example, should access provided by the project to education facilities, health care facilities, or food stores be considered? Please identify measures/data sources that would be readily available nationwide without requiring an undue burden on project sponsors to gather and FTA to verify the information.

Access is your ability to go places so that you can do things in a reasonable amount of time. Access reframes discussions of travel time: Instead of asking how long it takes to go to a particular place, you look at how many useful places you can go in a given time. In short, we’re talking about access to opportunity, which means not just work or school but your freedom to do anything that requires leaving home.

If you’re not familiar with the concept, please see my full explainer here. But the most important point is that when we increase people’s ability to reach destinations in a shorter amount of time, we are improving ridership potential, revenue potential, climate emission benefits, congestion mitigation benefits, overall access to opportunity, and personal freedom, and we can also measure whether we’re doing these things equitably. Access measurement can help meet all of these seemingly disparate goals.

Access and the Land Use Criterion

When the FTA asks about whether access matters, they are thinking about this in the context of their Land Use criterion. They deserve an answer on this, although they also should hear about how caring about access would affect other criteria they care about, which I’ll touch on further below.

FTA’s Land Use criterion measures how much population and employment is around the stops or stations of a proposed project. The point is to determine that there is enough demand adjacent to proposed facilities. (The criterion is not about the ability to generate future development – that’s under a different criterion, Economic Development.)

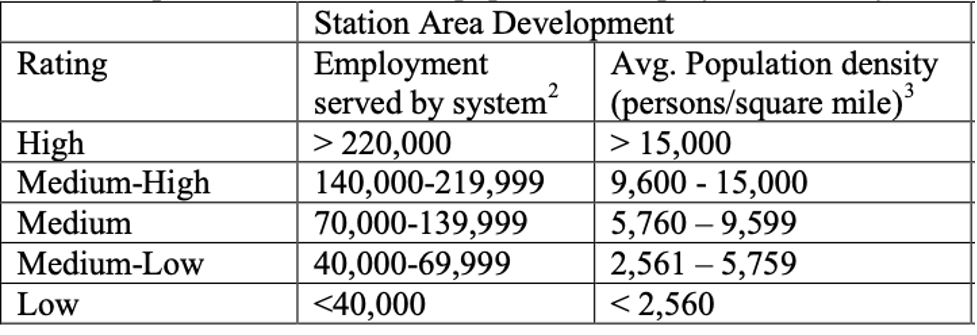

This table, from the FAST Updated Interim Policy Guidance dated June 2016, gives you a sense of how this evaulation works now:

Federal Transit Administration, Final Interim Policy Guidance Federal Transit Administration Capital Investment Grant Program, June 2016. p 15.

A project gets a higher rating if there’s more density around the station, and also if there’s more employment anywhere on the “system”.

But what do they mean by “the system”? Here’s the crucial footnote:

The total employment served includes employment along the entire line on which a no-transfer ride from the proposed project’s stations can be reached.

So all destinations that require a connection are excluded, while all destinations on the same line, even if they are an hour away, are included. In other words, as long as you get to stay in your seat, it doesn’t matter how much of your life you spend commuting. By contrast, if you can get to lots of jobs quickly with a fast transfer, those jobs don’t count in assessing the value of the line. Travel time, and hence access, don’t matter at all!

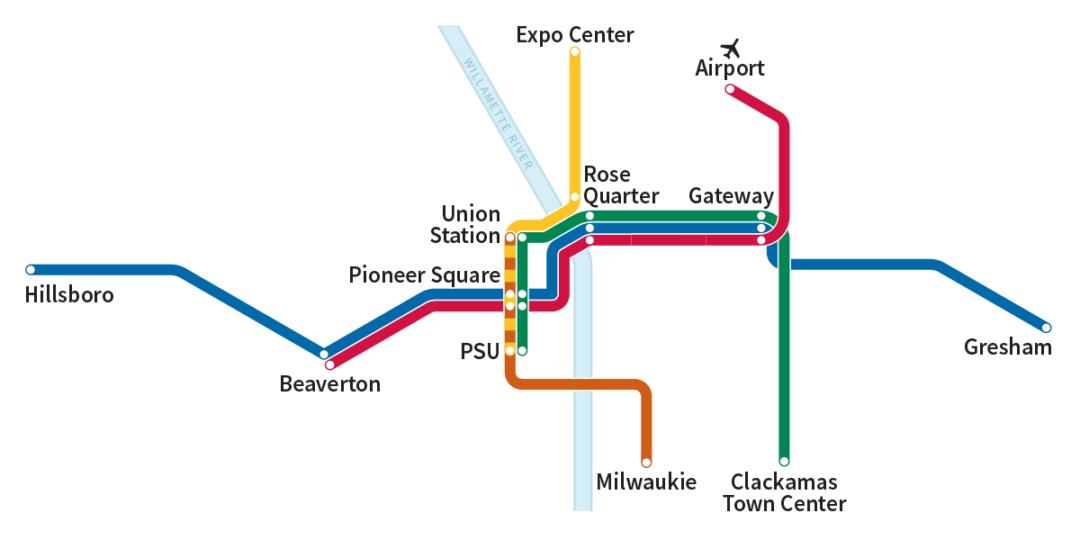

If you have an hour and 40 minutes to spare, you can go from Gresham to Hillsboro without leaving your seat! But should that count as access? Source: Trimet, Portland, OR.

For example, in Portland, where I live, a single light rail line will take you across the region, from Gresham to Hillsboro, in one hour and 40 minutes – far too long for a one-way commute. But under the current method, all the jobs in Hillsboro would be counted as providing value to someone in Gresham, while the jobs that are less than an hour away – on a trip that requires the train and a bus – count for nothing.

So “Employment served by the system” is really just “Employment served by the line” Likewise, the measure gives zero value to populations that are not at stations but that can get to stations easily via connecting buses. In short, the measure excludes all the benefits of actual networks, which are a bunch of lines working together to expand where people could go.

How would an access metric change this approach? Suppose the measure were something like “increase in the number of resident-job pairs that are connected by a travel time of 30 or 45 minutes.”

A resident-job pair is an imagined link between every resident and every job (or school enrollment). Each link represents a possible commute, which is an opportunity that someone might value, now or in the future. The number of resident-job pairs in a region is the number of residents times the number of jobs (or school enrollments). A very big number, but we have computers!

If we measured access in this way, what effect would it have on how FTA evaluate projects?

- It would still quantify the benefit of land use intensification around stations. These areas tend to get the largest access improvement from a project, so that improvement, multiplied by the density of population and jobs, would generate a higher score.

- It would measure what that density achieves for mobility. From a transportation perspective, the value of density around a line is that it provides the line’s benefits to more people, so that more people can get to more useful places sooner. So maybe we should measure what we’re really talking about.

- It would consider land use in the whole area that benefits from the project, not just around stations. It would reward communities that have thought about the total transit network more deeply and made some commitments about it. The tendency to propose a line in isolation, without thinking about its role in a network, is a very common problem in US transit infrastructure.

- It would refer to something that everyone cares about: their ability to go places so that they can do things.

What about equity? The current criteria specifically measure the quantity of affordable housing near stations, and its likely permanence – an important tool to discourage displacement due to gentrification. That measure definitely still matters.

But in addition, you could measure the access experienced by various racial or income groups, and make sure that this isn’t much worse what the entire population experiences. For low-income people, you could look at their links to low-wage jobs and educational opportunities, so that it emphasize the commutes that they are most likely to need or want. This would ensure that every element of the land use pattern is equitable in its most important aspect: the way that it ensures fast access to many opportunities.

Finally, FTA specifically asks whether access to “education facilities, health care facilities, or food stores be considered”. The answer is surely yes, because most transit trips are not work trips. We must measure access to all these things for populations likely to care about them, to the extent that the data permits.

For example, you could construct a database of all resident-grocery store pairs and run the same calculation, probably using a shorter travel time budget like 15 or 30 minutes. You could do the same for healthcare. You could construct a database linking school-age residents to school enrolments, and young adults to university and college enrolments. Retired people could be excluded from the residents-jobs database but included in databases of, say, links from residents to healthcare, food, etc. There are many ways to broaden the diversity of travel desires that a good network needs to serve.

The relative importance or weighting of all these measures would need more debating, possibly based on the size of each market in the region’s travel patterns with some bonus weighting for equity.

But to sum up: When we talk about existing land use as a transportation criterion, what do we really mean? I think we mean that the land use pattern contributes to a transit project’s ability to expand many people’s ability to get to many places in a reasonable amount of time. So let’s measure that!

Access or Prediction? A Broader Question for FTA

Land use is just one of the six criteria that FTA uses, and the one they have specifically asked about. The others are:

- Mobility Improvement

- Cost Effectiveness

- Environmental Benefits

- Congestion Relief

- Economic Development

Except for Economic Development, all of these are built on the same shaky foundation: a prediction of ridership well into the future. Access analysis may help to shore up those foundations, because an access calculation is much more certain than a prediction.

That should be especially obvious during the Covid-19 pandemic. The utterly unpredicted ridership trends of 2020 are just an extreme example of the kind of unpredictability that we must learn to accept as normal. As I argued in the Journal of Public Transportation, we can’t possibly know with certainty what urban transportation will be like in 10-20 years, or how our cities will function, or what goals and values will animate people’s lives.

Still, ridership prediction models generally begin with something like an assessment of access. If a project improves travel time for a lot of possible trips, that’s the starting point for a high ridership prediction. But then, predictive modeling mixes in a bunch of emotional factors that amount to assuming that how humans have behaved in the recent past tells us how they will behave in the future. This is equivalent to telling your children that “when you’re my age, I know you’ll behave exactly the way I do.”

Of course some human behavior is predictable. We’ll still need to eat. But the world is changing in non-linear ways, which means that the recent past is becoming less reliable as a guide to the future. So if we measured access, we’d still be measuring ridership potential, but without all the uncertainty that comes from extrapolating about human behavior, or telling people that you know how they’ll behave 20 years from now.

Here’s how the access concept could illuminate each of the FTA’s criteria:

For the Cost Effectiveness criterion, Congress has required that FTA measure the capital and operating cost of a project and divide that by the total number of trips (predicted by a model) to effectively measure the cost per trip. Since it would take an act of Congress to change this measure, it stands to reason that FTA should be looking to access measures as factors to use for other criteria. However, we should also assess projects based on the increased access provided per dollar expended.

For the Congestion Relief criterion, FTA measures the number of new riders on the project, yet again based on ridership prediction. We know that transit expansion by itself doesn’t solve congestion, just as road expansion doesn’t either. But transit expansion can do very important things much better than road expansion: it can allow for drastically more economic growth and development at a fixed congestion level and improve the ability of those who cannot drive to participate in the life of the community. It does this by expanding the access to opportunity that’s possible without generating a car trip. So, there’s a good role here for access measures as an indirect way to tell us whether a transit project has a high likelihood of providing an option to avoid congestion.

For the Environmental Benefits criterion FTA looks at changes in predicted air pollution, greenhouse gases, energy use, and safety benefits. Most of these factors are calculated based on predicted ridership. So, FTA is building many measures on the questionable assumption that ridership is predictable. Again, we know that greater access tends to mean greater ridership, which means great environmental benefits. Perhaps we need more research to be able to quantitatively tie improvements in job access to environmental benefits. If FTA sticks with its current measures for environmental benefits, it makes the case for using access measures in other criteria even stronger, if nothing else than to provide a wider range of measures that aren’t tied to one modeling outcome.

For its Economic Development criterion, FTA evaluates how likely a project would induce new, transit supportive development in the future by looking at local land use policies. How might access be a useful measure here? It depends a lot on what kinds of real estate investors we have in mind. The real estate business already calculates car access for practically every site they consider. They should be encouraged to care about transit access (and they sometimes do).

To Sum Up

All of the FTA’s criteria are attempting to answer the question “Which of these potential transit projects across the US is the best investment and therefore worth of funding?” That begs the question of what we, citizens of the US, think we value about our investments in transit. Access starts with one insight about what everybody wants, even if they don’t use the same words to describe it. People want to be free. They want more choices of all kinds so that they can choose what’s best for themselves. Access measures how we deliver those options so that everybody is more free to do whatever they want, and be whoever they are.

Should we be investing in projects that score well on predictions of what we think people will do in the future? Or should we be investing in projects that we can geometrically prove will drastically increase the average person’s access to opportunity?

Whatever your view on these topics, now is the time to respond to the FTA’s questions!

My personal thought is that, in an idea world, the FTA would get out of the business of judging specific projects for their grant-worthiness altogether. The current way of doing things is a mess – lots of cities spending lots of resources preparing grant proposals with very few getting anything in return. It also leads to projects oriented around what’s most likely to get grant money rather than what’s actually best for the mobility needs of the city. For instance, downtown streetcars typically perform terribly in terms of mobility gained per dollar spent, but the FTA has been generous at giving them grant money, so they get built.

Instead, I would like to see the FTA give each transit agency a form of block grant for operations where they get money every month based on some combination of their daily ridership and the total number of people that live or work in their service area, regardless of whether they ride transit or not (including the latter criterion gives agencies that get poor ridership because they provide poor service money to improve their service and get more riders).

For capital projects, I would like to see the FTA function more like an infrastructure bank. Do loans instead of grants, and evaluate the loans based on the agency’s ability to repay it, rather than the project itself (as long as the project is transit related). The idea is to give any transit agency the ability to borrow money for capital projects at the same ultra-low interest rates the US government pays on its debt.

Of course, one downside to having federal support for transit operations is that the moment the party in power changes, the span and frequency of service on your bus route could change immediately and dramatically. But, the flip side is that it leaves the transit-dependent population much more motivated to vote than under the current system, where the relationship between the party in power and the wait time for your bus is much weaker.

I also realize that the above is all probably impossible under current law, and would likely require an act of congress that has no chance of ever happening. Still, in an ideal world, I think it’s better than the current mess where cities waste time and money competing with each other for grants on who has the best project based on outdated criteria, and the vast majority of cities walking away with nothing.

asdf2: Interesting ideal world. Many (mostly much smaller) countries have centralized public transit operations funding. In many others, like Canada and Australia, the state/province is sovereign and does most of this. Generally there are processes in place to keep the transit budget stable, like the semi-autonomous transport authorities in many cases, but of course in most countries both parties care about the functionality of cities.

I agree. I think things should be reversed, and the federal government should chip in more for maintenance and operations, and less for new construction. The latter is always favored by local politicians (who love a new ribbon cutting ceremony) while the former is reduced as time goes by. It isn’t just transit, of course, it is everything, which is why we have a major infrastructure problem in this country.

This also minimizes the problem that the author described. Just about any meaningful metric would have to consider the overall network, and the overall network is highly dependent on service and maintenance.

You can build all the infrastructure you want, but frequency and reliability are crucial. Washington DC built the greatest post-war subway system in the United States, but they saw declining ridership because they couldn’t keep the trains running. This is for a major system that carries the bulk of the riders in the area. It is much worse in places like the Bay Area, where BART is extremely dependent on the buses. If the buses don’t run often enough, they can’t feed the trains, and ridership on both systems goes down.

The drawback to asking cities to largely pay for new infrastructure themselves is that low income areas wouldn’t have the money for new infrastructure. For the most part though, this is no longer a problem. This isn’t the 70s. Cities that could really use some new infrastructure (e. g. L. A. or San Fransisco) are relatively wealthy. Suburban poverty has spread (to places like Ferguson) while Rust Belt cities are hollowed out. These are areas that need service — or money to fix their aging system — not major new projects. Detroit doesn’t need another people mover or streetcar, it needs better bus service.

This also solves the major political problem with transit infrastructure spending. A sensible metric would tend to focus almost all the money on a handful of big cities in reliably Democratic states (New York, L. A., Chicago, San Fransisco). So either the measurements are bent to favor projects in swing states, or it becomes tough from a political standpoint. Service and maintenance spending doesn’t have this problem. You can spend money in states like Arizona, Ohio and Georgia without wasting it. Like Detroit, the cities in those states need money for better service and maintenance — essentially better frequency — than anything else. Its not hard to argue against some of the major transit proposals put forth over the years. It is really hard to argue that the buses and trains come too often.

I agree with your criticisms of long-range forecasting but think there’s a substantial role for near-term (current year or opening-day) forecasts when thinking about the impacts of a proposed service change or the inequities inherent in the current system. Because these rely on more timely data about travel behavior, land use, and levels of service, we have more confidence that their results are meaningful. These forecasts can provide information about how travel times (walk, wait, in vehicle, and transfer), number of transfers, and out-of-pocket costs change or differ across people and places. (E.g., the proposed service change will increase origin-destination travel times for low-income transit riders on average by 8 minutes).

To be sure, accessibility (access/freedom) is super important. But we should also look simultaneously at expected impacts on transit riders today. Activists and advocates always request these types of measures when service changes are being proposed.

The problem is that even the near-term forecasts are flawed if they don’t include the overall network. Consider this example:

Sound Transit is building several mass transit lines, including one that will go north from downtown. They initially rejected a station at NE 130th (roughly here: https://goo.gl/maps/tLMFkJqTYsRhQwDB7). At first glance, this was a reasonable decision. Infill stations aren’t that expensive, but there is nothing there. Even with TOD, there would be very few walk-up riders (space is taken up by the freeway and parks). There were no plans for a large park and ride lot, either. As a result, ridership estimates were very low.

Except they forget to consider the network. This is a good map of the existing system in Seattle proper: https://seattletransitmap.com/app/. This will change in a few weeks, as the light rail line goes further north (but not as north as NE 130th). The northern terminus will be at the Northgate Transit Center (shown on the map as “Northgate TC”). The buses will be restructured, but not for the examples I give and thus it is easier to look at the existing network. Notice the neighborhoods called “Lake City” and “Bitter Lake”. These are large, relatively dense neighborhoods. Notice especially Bitter Lake, and how it is connected to the Northgate TC, and new light rail system. They are left with an infrequent bus (running every half hour) that takes a roundabout route to the station. This won’t change with the new restructure. A new multi-billion dollar expansion, with trains eventually running 3-5 minutes all day long, and new stations in very popular neighborhoods (including the biggest university in the state, containing several new skyscrapers) is just out of reach for Bitter Lake. Riders will do what they have always done. They will take a direct bus to downtown. To get to the university, riders will take that same bus, and transfer to a very slow bus. This is true for just about all the destinations on the line. Despite the fact that the station is only 1.2 miles from the neighborhood, the subway line may as well not exist.

Notice also that Bitter Lake and Lake City are not directly connected. A trip between two of the most populous neighborhoods in north Seattle involves an extremely long detour. By bus it takes about 45 minutes (https://goo.gl/maps/sj2KdTjjrc6m7g6o8) while driving usually takes less than 10 (https://goo.gl/maps/tfrX8nQvcSZToGuv9). This has other ramifications. In north Seattle, most of the buses go north-south, including the highest ridership buses in the system. The lack of good east-west crossing leads to very painful transfers (https://goo.gl/maps/o2AdZm8XpGthoquT6). The system desperately needs a frequent bus along the 125th/130th corridor, but can’t justify it, as they spend so much money sending the buses twisting and turning to serve Northgate.

None of this shows up in the metrics for 130th. Not the significant savings that come from routes that go east-west instead of to Northgate. Not the increased ridership on the train from places like Lake City or Bitter Lake. Not the overall increase in ridership that comes from building a better network. By focusing entirely on walk-up (or park and ride) passengers, we get a very distorted view of this station, and its importance — in both the short and long term.

I’m not familiar with the local situation you describe and the problem that you’re highlighting isn’t clear to me.

But if we have a good sense of how existing riders are using the network (that we get from a high-quality transit rider survey), there would be no issue with assessing how different network configurations and service patterns will affect different riders. The steps are easy:

1. With the existing network and the existing distribution of trip origins and destinations, calculate trip characteristics for all riders (e.g., initial walk time, wait time, in-vehicle time, transfer time, time to walk to destination, costs, number of transfers, etc.).

2. With the new network and the existing distribution of trip origins and destinations, calculate the same characteristics for all riders.

3. Compare outcomes for different groups or places to get a sense of how the changes will affect current riders.

If the network data are bad, then the outputs will not be useful. In that case the input data should be improved, but the overall method is sound.

“I’m not familiar with the local situation you describe and the problem that you’re highlighting isn’t clear to me.”

That is why I referenced maps and gave a detailed explanation. I find it helpful to look at a real world example, but we can talk about it from an abstract standpoint as well.

There is a subway line going north-south. It passes right by major destinations, then goes next to the freeway. There is basically nothing at the freeway, especially at the proposed station. There are, however, major neighborhoods to the east and west. Buses can quickly and easily connect to the station from both sides. Buses will be responsible for most of the ridership of this station. Furthermore, the buses that connect to the station from either side will also connect with each other. This means that riders can quickly get from one neighborhood to the other. There is more. There are buses going north-south on either side as well. This bus — which connects to the subway station — will also enable a lot of other trips. It helps provide a much better network.

Yes, you can calculate the effectiveness of such a network (as you outlined). But that isn’t being done! It wasn’t done by the local agency in charge, nor is it being done by the Feds. That is the point. This is just one example of how limited the thinking is. If you only focus on the number of people who will walk to the new line and walk to their destination, you get a very skewed view of the system. You have to look at the network.

Great – it seems like we agree.

Access is undoubtedly an important measure, and is definitely under-used as a metric of success or value in many transit system evaluations.

I do have one quibble with your argument, however. Measuring access now and using it for long-term projects into the future is *still* making static assumptions about human behaviour (that the destinations you measure access to are important and will be into the future), as well as assumptions about future land use. While I do think it’s not as explicitly modeled as with a standard econometric behavioral model, it’s still implied.

One way to potentially fuse some of that together and add flexibility is to get into the habit of bundling destinations into a weighted “basket of destinations”, something I argued in a JTG paper. Then the trick becomes figuring out ways to determine what those bundles should be.

Ultimately, I think there needs to be more research done on how access translates into use (of which ridership is one metric), and how that happens.

Referenced Paper:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0966692321000028

Alex and Willem

Alex: I agree completely that there’s role for understanding current needs and maybe even near-term forecasting, but the kind of transit infrastructure we’re talking about here has to be useful for decades if not centuries, and the present is just too brief a time to be the the only consideration or even the main one. Since the narcissism of the present will dominate the project politics anyway, I want to highlight measures that push against the present bias, because there’s literally no other way to give our unborn grandchildren a place at the table.

We all live inside our grandparents’ bad infrastructure design decisions — decisions that made sense at the time, in the culture of the time, for the people who were being listened to at the time. You can work to make that present-oriented conversation smarter, more fact-based, and more inclusive/equitable, and I support that 100%, but your approach still leaves us saying that our grandchildren will be just like us in all kinds of ways that we have no right to assume.

How do we know what our grandchildren will want? Two ways: (1) We can assume that they will want what history and biology tell us that humans have always wanted and (2) beyond that, we can focus on giving them the freedom to be whoever they turn out to be and want whatever they turn out to want.

For example, under (1) we have the biological needs that drive a lot of our daily activity, but also historical insights like Marchetti’s Constant, which help us set useful travel time budgets for a daily trip or “commute.” We can do some philosophical work to delineate the boundary of those two categories. This is where I was going with the Bortworld thought experiment in my JPT paper: https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1824&context=jpt

Willem raises a good point about how we can know, on behalf of our grandchildren, what the relative importance of different kinds of destinations will be. Biological and historical knowledge like what I outlined above help. Finally, yes, that weighting will still be a judgment. But if we could get to the point where we were arguing mainly about that I think we’d have made transformative progress in how we think about infrastructure. More on that here soon.

I think Willem’s point about having to make assumptions about future land use–either how it changes or assuming it stays constant–clarifies that accessibility or freedom analyses are still subject to at least some of the limitations of long-range ridership forecasts.

In terms of infrastructure, I’m fine with having different standards for fixed-guideway projects with high capital costs and longer-lasting impacts on urban form as compared to bus network redesigns or other tweaks to the bus network. Although I wonder how much land use and density is already baked in and how that differs by urban areas. Will the locations of high land use intensity look much different in 50-75 years, in terms of their locations, than they do today? If not, then holding land use constant and also using current/near-term forecasting can both provide important insights about impacts now and in the future. I don’t think we have to pick one set of metrics or approaches over the other. Both are important.

One key area where I think we differ is in our relative weighting of future vs. past impacts. I definitely appreciate your future orientation–this is important from a climate, health, sustainability and resilience perspective. But I think to make traction on these issues and to get residents to buy into any specific public transit vision, we (academics, practitioners) have to acknowledge that transportation infrastructure development (highways *and* transit) has historically had baleful effects on low-income people and people of color in the US. Black people were especially negatively affected throughout the 20th century and continue to bear the brunt of many of the transportation system’s most direct impacts while not sharing fairly in the system’s benefits.

I see looking at impacts on current riders and near-term forecasting as at least partially atoning–or at least acknowledging–these historical impacts. In conducting a current/near-term analysis, we’re saying that we value the experiences of current public transit riders and want to understand how our proposed changes will affect them. To be sure, there’s a lot more than can and needs to be done in this regard (this pending TCRP project will help to suss out exactly what a reparative approach for public transit planning/policy could look like: https://apps.trb.org/cmsfeed/TRBNetProjectDisplay.asp?ProjectID=5071). But jumping straight to the future without acknowledging the past seems like a surefire way to alienate the essential riders upon which public transit depends.

The folks at the Untokening Collective have written about this in their “Principles of Mobility Justice,” one of which is the following: “Mobility Justice demands that we fully excavate, recognize, and reconcile the historical and current injustices experienced by communities — with impacted communities given space and resources to envision and implement planning models and political advocacy on streets and mobility that actively work to address [the] historical and current injustices [they experience].” (http://www.untokening.org/updates/2017/11/11/untokening-10-principles-of-mobility-justice)

Current/near-term forecasting doesn’t live up to this high standard on its own, but providing resources to communities to vision future transportation systems and to understand how their travel outcomes (in terms of performance, not necessarily choices) will differ in those futures might get us moving in the right direction.

Alex

We are in complete agreement about the need to show the impacts of proposals on the present, especially relatively short term work like bus network design. That’s what we do in all our projects.

Access analysis honors the future but is also an important way to talk about the present. For example, we can talk about the impact of a service change on the access to opportunity of existing riders based on their boarding location, so that we are specifically addressing the benefits and disbenefits that each such rider will experience. This can help riders see beyond an understandable initial assumption that all change is going to be bad for them.

There’s also a space for access analysis in giving elected officials another way to think about what they are hearing from the public, and to relate a service plan debate to larger goals that they care about, because expanding access supports so many of those goals.

But you’ll have to explain how forecasting serves the goal of “excavating … historical and current injustices.” How does predicting human behavior the near future help us understand the past, or our moral options for rectifying the injustices of the past? That one I just can’t follow.

It seems like we also differ in terms of whether we think access analyses are enough on their own to demonstrate present-day impacts. The analysis you describe based on boarding location sounds helpful. I’m arguing that in addition to evaluating those quantities, we should also look at impacts on *current trips* and *current riders,* summarized by place or for specific groups (e.g., low-income people, Black people, equity-priority neighborhoods, etc.). Access it great, but it does not tell us how people are using the system today and how a proposed change will affect the trips they currently need to undertake.

Our knowledge about the injustices of the past informs the places and groups that we think it important to analyze. A high-quality transit rider survey will capture the travel behavior of a sample of transit riders. These results need to be carefully weighted and expanded to represent all transit travel. This weighted and expanded sample is our best representation of the full range of travel being undertaken on a particular system. Trip characteristics can be modeled to assess how they change from a base (no-build) to a build scenario. These changes represent the real impacts that will be experienced by actual travelers today and can be used to understand differences between groups. If done well, this analysis will provide insight into current injustices, if any exist (e.g., wide disparities between the trip characteristics between places or groups).

If desired, appropriately crafted simulation models can also be used to understand how behavior will change in response to changing levels of service (or demographics or land uses). Model results can also be used to assess current injustices and to help us understand whether we are making progress towards redressing historical wrongs.

We certainly don’t disagree about the value of studying how the system is being used now, and evaluating impacts of changes on existing riders. We see the value in using rider surveys for this purpose, alongside access analyses that show how a network proposal changes what people *could* do (but aren’t doing now because the transit system doesn’t let them).

But I’m still puzzled about how models that predict “how behavior will change” are helpful in understanding or rectifying past injustice — unless you just mean really safe predictions such as “if we make high-demand trips possible that aren’t possible now, people will begin making those trips.” Is that all you mean?

That’s not all that I mean. If we have a “good” rider survey collected recently we can use that survey to estimate a ridership model that will help us understand how changes in level of service and land use will affect transit use. The changes need not be limited to “high-demand trips.”

If we constrain our forecasts to use near-term or current year data, then we will have more confidence in the outputs we’re generating than if we use a 30- or 50-year horizon.

And if we examine outcomes for groups that have historically experienced injustice, our results can speak to how their experience of using public transit will change.

I’d like to see the Feds create a tendency to oversupply transit services.

That is the greater the frequency, coverage and span a system has the greater the amount of money the system gets.

I don’t know how many buses are too many on a rout, but is a frequency of every five minutes too much? Every three minutes? So set the grants to support whatever the maximum workable frequency might be.

And:

Additional money for using a grid system instead of hub and spoke.

Additional money for every all-electric bus and the infrastructure to support them.

Additional money to make sure the drivers, mechanics and technicians are highly paid.

Additional money for cities and counties that eliminate off-street parking minimums.

Additional money for cities and counties that reserve lanes for buses. That is where you have two or more lanes in a direction one would be for buses only.

I don’t know if any of this is possible given the legalities of how things are funded but I think it would induce demand for ridership and reduce the utility of private automobiles.

The service situation can be done relatively easily via grants, as asdf2 suggested above. Matching grants for transit service as well as maintenance would make a lot of sense. The agency would then decide whether to put that into running some buses every five minutes, or making more wide spread improvements. Likewise, grants for electrification are pretty simple and straightforward. I wouldn’t bother trying to legislate a design — that is extremely difficult, and agencies have a self interest in creating an effective system. You could allocate grant money for restructures, but those are relatively cheap. In general, any restructure is a lot easier with more service. Not only does additional service make it easier to implement a grid (more frequent buses mean that transfers are less painful) but being told that the buses will be a lot more frequent (instead of a little more frequent) make the loss of a one-seat ride more palatable.

Funding street improvements is an excellent idea, and could be implemented relatively easily. You could estimate the amount of time saved for the change divided by the cost. This time saved includes the overall network (a bus becomes more popular if it is faster). This would allow an agency to focus on what they consider important, instead of trying to game the system by adding bus lanes where it is politically easiest.

One thing to add to the list is tying transit funding to smart land-use choices. Up here in Canada, the conservative party platform (yes, the right-leaning party) proposed tying transit investment to transit-oriented development, which is a theoretical mechanism for getting cities to properly zone and encourage denser, more transit-focused development instead of unsustainable sprawl. Such a plan, if actually properly executed, would bode well for transit in Canada.

“I don’t know how many buses are too many on a route, but is a frequency of every five minutes too much? Every three minutes?”

Existing bus routes in some US large cities already have frequencies like this. For example, when I lived in Chicago, several routes like the #66, #79, etc operated every 2-3 minutes during the height of the peak. Generally, you can never have “too many” buses on a route until each one starts interfering with the operation of the next one, eg the preceding bus stopping on the road to pick up passengers is blocking the next one from moving down the street at a reasonable speed. This generally doesn’t happen until you get frequencies of a minute or less, especially if the street has more than one lane in each direction.

My original comment emphasized federal funding for operations. But electrification of buses is another area that should be deserving of federal funding also.

As climate change is a global phenomenon, each city in isolation is nearly always better off spending their local $$ running their diesel buses more often, rather than replacing them with electric buses. Federal subsidies can help mitigate this.

Also, much of the reason why electric buses cost so much more than diesel buses is lack of economies of scale in the electric bus market. The financial might of the federal government can help mitigate this.

Note that electrification isn’t necessarily strictly confined to battery buses. There’s also the older technology of trolley wire, which works well for short routes that run very frequently, allowing a large number of trips to happen over a small amount of wire. One could even imagine a hybrid system where buses run on diesel power in the suburbs, charging batteries in the process, then use the stored power in their batteries to run emission free in the downtown area, where the shear volume of buses makes local pollution more of a problem.

I would like to see them consider what percentage of trips are made on a monthly family pass, the more the better.

When I’m just going to work and back because that is the only thing the local system is useful for paying each day isn’t too bad, between vacation, out of town trips and sick days I’m money ahead at the end of the year vs their pass (this us very much different in different towns ) if the system wasn’t so bad I would get the pass because it only takes a few more trips and it is always worth it.

Family, because if you have kids, driving everywhere can be cheaper than a bus pass for everyone, so this ensures they get the right pricing in place that families will use the system.

Of course what im really measuring is how useful people find the current system. I don’t care how many people ride any particular line, I care about how much of the town finds it useful.