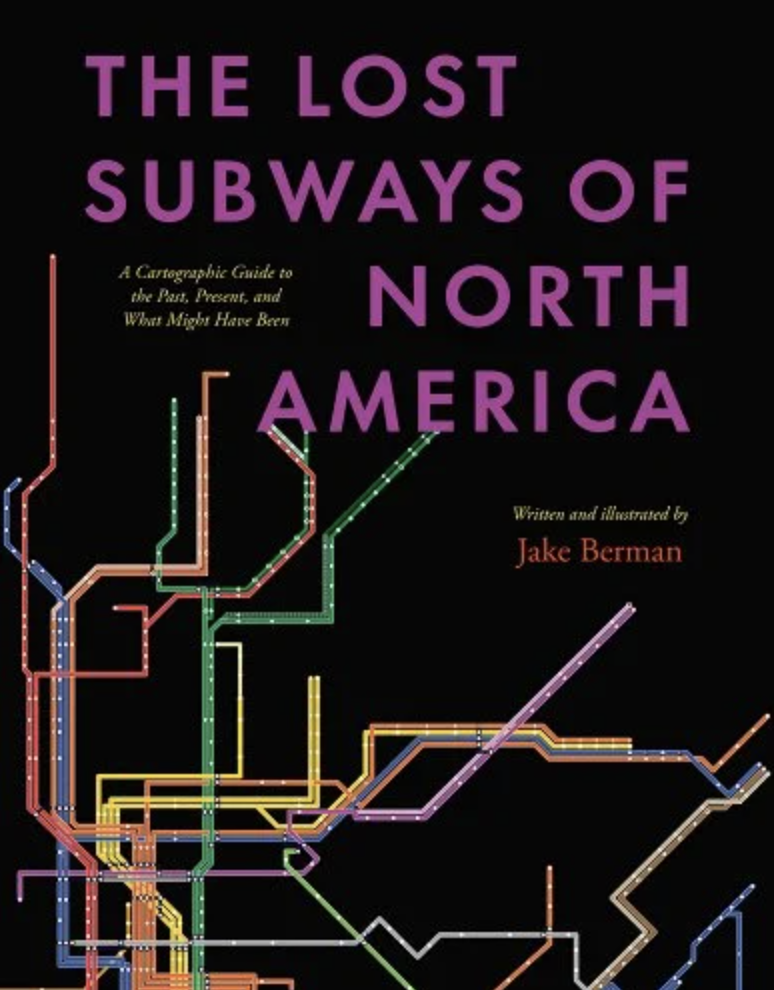

If you are looking for a gift for a transit-lover or urbanist, here’s something even better than an ugly sweater. I can heartily recommend Jake Berman’s beautiful and engaging book The Lost Subways of North America.

If you are looking for a gift for a transit-lover or urbanist, here’s something even better than an ugly sweater. I can heartily recommend Jake Berman’s beautiful and engaging book The Lost Subways of North America.

Berman has constructed beautiful period maps of North America’s many “lost” rail systems, including the original streetcar networks of many cities and the numerous rapid transit maps that were sold to voters, often unsuccessfully, over the years. But this is also a fine introduction to the history of rail transit in 23 North American cities. The chapter on each city tells some aspect of the story of how the rail transit, or lack of it, came to be.

The book has a blurb from credentialed transit historian Nicholas Dagen Bloom (The Great American Transit Disaster), so you can feel confident in Berman’s work as history. The tale of each city’s transit wars is both truer and more interesting than the old conspiracy theory about General Motors. Throughout the middle and late 20th century, countless leaders worked hard to create the transit renaissance that they knew had to happen sooner or later, and that in many cities is finally happening now. The failure of some of these schemes, and the success of others, makes for a lively read.

Berman is fully aware of the dangers of his title, and his section on terms suggests that he’s done time in the trenches of grim arguments over what subway, streetcar, and light rail really mean. The title Lost Subways suggests an ideal world of fast underground transit that’s routine in Europe and East Asia but that was abandoned or stillborn in most of North America. But much of North America’s rail transit is on the surface or elevated, and it moves at a variety of speeds, from giant BART trains rushing under San Francisco bay to cable cars and streetcars in traffic that are sometimes not much faster than walking. Rail, in short, is a poor shorthand for speed or even usefulness, and in a few cases, as in Los Angeles and Pittsburgh, Berman acknowledges where busways have become a critical part of the rapid transit network, as they are across much of the developing world. But Berman gracefully deploys the hook of his title without being hung up on it himself. At the end, you’ll come away with an appreciation for the diversity of North American transit problems, and it will be clear why “subways everywhere” has never been the right answer to every city’s needs.

Ultimately, all transportation problems are land use problems, and these problems were created by zoning and other development policies. Berman takes every opportunity to point out where these policies have shaped cities to be better or worse transit markets. The point is most dramatically made in comparing Dallas and Houston. The Dallas area built the nation’s largest light rail network but maintained a culture of strict zoning controls that prevented much development from happening around the suburban stations. The result is an overstretched low-ridership network that currently runs only every 20 minutes, and a huge need for a robust bus network to go where the development actually is. Houston has much less light rail but more permissive zoning laws, which has allowed development to respond to transit more rapidly and at scale. So while Houston’s network goes fewer miles, the stations it serves are more likely to be your destination. Berman weaves the zoning story into the transit story in a way that must be done to explain why North America’s transit situation is what it is.

While it tells many frustrating stories, this is not a sad or angry book, as many books on this topic justifiably are. The short chapters and beautiful maps make it a pleasant browse, arousing curiosity and encouraging the reader to want to know more. It’s a beautiful addition to a library, or a coffee table, in any home where people care about cities.

May I politely note that Berman seems to have skipped Baltimore. While successive GOP governors have obstructed extensions, the Baltimore Subway has run long enough that it is time to replace the fleet. The “Purple” LRV line generally thought of as part of the Washington DC system, is entirely in Maryland, and thus was also delayed both by GOP sabotage and local auto-centric NIMBYs along the route.

Turns out that when Berman did a presentation at the NY Transit Mueum, he effectiovely did a ‘bonus chapter” on Baltimore. video link

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3Gaxxp2Jsz8&list=PLU0SMBX3qgRhcwkMNfzne2UHR24aFEnjr&index=1&pp=iAQB

I

During his talk on CTA in Chicago he omitted some details which I think are critical to understanding the loss of streetcar service in favor of buses, and other rail amputations.