As the State of Illinois launches a complex conversation about how to fund public transit into the future, our firm has been doing planning work with two of the three big agencies in the Chicagoland region: Chicago Transit Authority (CTA), which mainly covers Chicago, and Pace, which covers almost all Chicago suburbs. I thought it would be a good time to share thoughts from both of those projects.

Recently, I listened to a big State Senate Transportation Committee hearing in which all of the agency heads in the region spoke. The key issues facing the region are:

- a “fiscal cliff” which threatens all the agencies in 2026, as Covid relief funds run out, operating costs go up due to the difficulty of hiring workers, and yet pre-pandemic fare revenue can’t be expected to return.

- a proposal to consolidate the three agencies (Pace, CTA, and the regional rail agency Metra) into one giant agency, supposedly to save money or achieve efficiencies.

To help with these debates, I want to lay out my view here why the agencies need more funding, and why I think consolidation would be a bad idea.

Why the CTA Needs More Money

We just completed a Framing Report for Chicago Transit Authority’s Bus Vision Project. We put a big effort into this report because we wanted to create a sample of all the things we could do, especially in access analysis, to illustrate exactly how a transit system functions and how it addresses various goals.

The report took a long time to write and was somewhat overtaken by events: You’ll notice that it mostly describes the 2019 network, and then more briefly describes what’s happened since then. As CTA recovers from the pandemic-related hiring crisis, the 2019 network is not exactly what it should go back to, but it still represents the most recent “non-crisis” state of the network, so it’s a good point of reference.

The report’s most important point is that Chicago’s geography creates a tradeoff between the goal of ridership and the goal of equity, because Chicago has a large low-income and racial minority population living in especially remote parts of the city, often at low densities or in areas with other physical barriers to service, where service to them is expensive per person to provide. This geography has a history of course, often tied to racist policies and practices that were common in the past.

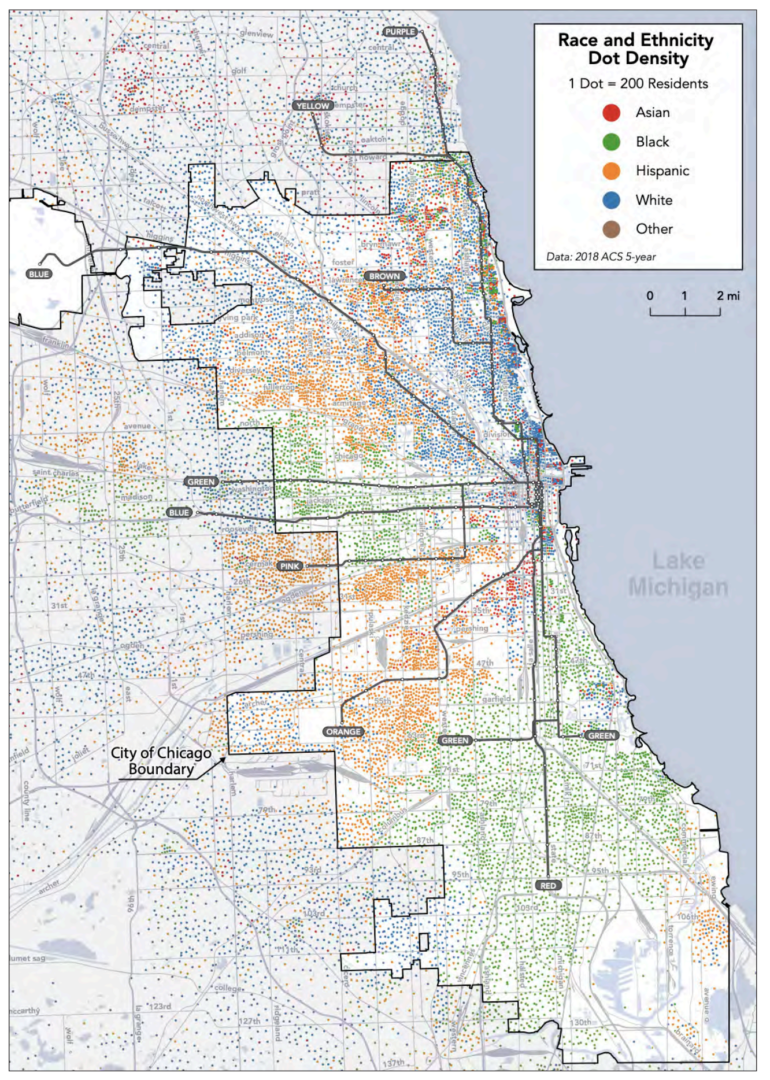

The racial geography of Chicago and its inner suburbs, from our report. White people (blue) live mostly around downtown or in the northern third of the city, where density is high and travel distances are short. The rest of the city features “pie slices” of mostly Hispanic/Latino (orange) or mostly Black (green) areas. Black people (green) dominate the remote South Side, where they tend to be furthest from jobs and opportunities.

The ridership-equity tradeoff is a consequence of the mathematically inevitable ridership-coverage tradeoff. A ridership-equity tradeoff arises wherever a ridership-maximizing network design would inadvertently disfavor disadvantaged groups, because those groups tend to live and travel in places where their needs are more expensive per person to serve. Chicago has this problem in a big way.

We have two key findings about this problem:

- Transit is doing a lot to help, and it can do more, but only by running some services that won’t be justifiable on purely ridership grounds.

- Transit by itself cannot be expected to heal the legacy of decades of racist land use and real estate policies. Only redevelopment that reduces the isolation of low-income and minority areas, and adds more jobs and educational opportunities near them, can do that.

This conflict between ridership and equity goals is important because CTA has long labored under an unrealistic requirement to pay 50% of its operating costs from the farebox. In 2010, funding shortfalls related to the recession led to service cuts that made it difficult to maintain equity.

A new vision of CTA will need to create a set of standards that will accurately reflect the real goals that motivate support for public transit. These will surely include an equity goal that will be a counterweight to a ridership goal, because it will justify service expansions in disadvantaged areas despite their lower ridership potential. The balance between those competing goals will need to be chosen, as a political decision. But as always when there are tradeoffs, expanded funding makes it easier to do both.

Chicago is a city with vast unrealized transit potential. Its grid geography allows for especially efficient network structure. It has many areas that could be redeveloped in more transit-oriented ways, especially to improve the balance between housing and activities on the South Side. But it is held back by two things: inadequate protection from traffic, which CTA and the City of Chicago are also working on, and inadequate frequency, which is purely a matter of operating funds.

I will be presenting to the Chicago Transit Board (which governs CTA) on this report later this year, and that will be the end of our contract. I don’t know if we’ll have any future role in CTA’s Bus Vision Project. Meanwhile, if you want to understand the CTA’s situation in more detail, please look at our report.

Why Pace Needs More Money

In the hearing, one Senator emphasized that he wanted to talk first about a vision of service, then about governance, and finally about funding. That suggests that rather than just talking about how to address the “fiscal cliff”, so as to keep things as they are, this would be a good time to present a positive vision of the level of service that could transform the relevance of public transit across the region.

That’s what we’re doing for Pace, the agency that provides bus services to almost all of the Chicago suburbs. Later this year we expect to release a report that will show both what Pace could do if its funding returns to 2019 levels, which is not much, but also what it could do with an expansion of funding. The public outreach process on those alternatives will happen toward the end of 2024.

There’s one finding I can share now, which won’t be a surprise to anyone who knows the network. Pace has never been resourced to keep up with development and population growth of the last 70 years.

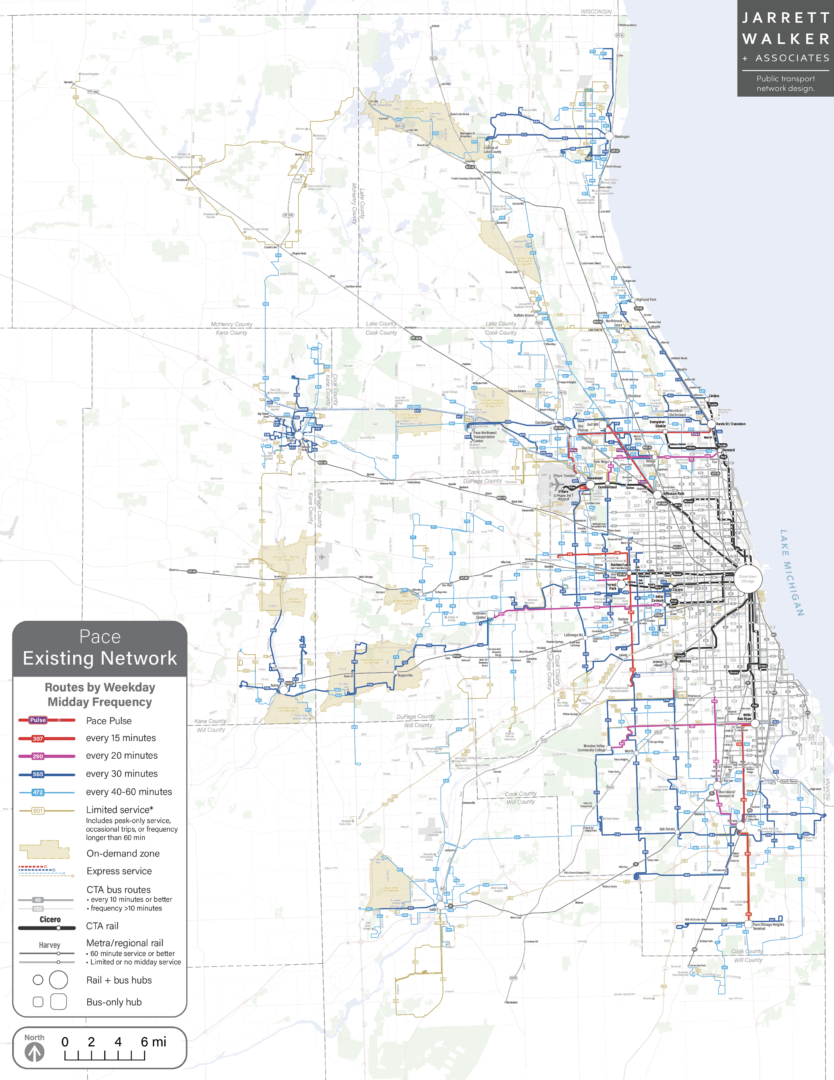

If you look at the Pace network, you’ll see intensive local services focused on places that were already built out by the mid-20th century, mostly around the edges of Chicago and in the large, old satellite cities of Waukegan, Elgin, Joliet, and Aurora. An enormous area of newer suburban development has very little service, just a thin scattering of hourly bus routes and a few rush-hour express services.

The Pace network, with red denoting high frequency. (See legend.) Service is concentrated on the edges of Chicago and in the older satellite cities, leaving large developed areas, including much of DuPage County, unserved.

So when regional leaders think about how Pace should be resourced, they have to keep in mind that for decades Pace has been unable to grow as the region has grown.

That’s why the Pace project will show two alternatives for a substantial expansion of service, which is currently unfunded. We need to show people what it would mean to plan based on needs rather than just on constraints, and how that network could transform the possibilities of life in all of the suburban cities. These scenarios would bring service up to a level that comparable suburbs in many other states already have.

Will Consolidating the Agencies Help?

As I am a consultant who sees both CTA and Pace as clients, you should not expect me to disagree with their managements in public. So of course you should expect me to share their opposition to consolidating CTA, Pace and Metra into a giant agency.

But I really do think it would be a bad idea, for the same reasons that I’d oppose similar moves to create a single giant agency for the San Francisco Bay Area, which has also been proposed.

First, there aren’t that many economies of scale that arise from consolidating agencies as large as CTA and Pace. The resulting agency would be huge, and you should expect bureaucratic inertia to increase with hugeness. Two 50-bus agencies probably have a lot of duplicated administrative functions that you could consolidate in one 100-bus agency, but at the already-huge scale of CTA and Pace, further consolidation probably won’t eliminate much administration, because the job the new agency would have to do is so vast and diverse.

More importantly, dense core cities like Chicago and San Francisco have profoundly different transit needs and transit politics than their suburbs. Many US cities that are served by regionwide transit agencies have constant conflicts with their suburbs over how to get their needs met. Transit needs per capita are higher in dense cities, yet it is often difficult to get a regional transit authority, especially one dominated by suburban cities, to apportion to the core city more than its per capita share of service.

Dense cities are also where the most can be achieved through intimate coordination of transit planning, land use planning, and street planning. Since the latter two are controlled by city government, a lot can be achieved by urban transit agencies that are close to city government, if not part of it. San Francisco already has the model of an integrated transportation agency that handles both transit and street planning, allowing those functions to be harmonized. If you were going to merge CTA with something, it might make sense to merge it with Chicago Department of Transportation. Even now, CTA is ultimately answerable to the Mayor of Chicago, just as the SFMTA ultimately answers to the Mayor of San Francisco, so the Mayor is in the position to make transit, street planning, and land use planning work together.

In the hearing, Pace Executive Director Melinda Metzger argued that a combined Chicagoland public transit agency would also be bad for the outer suburbs, because Chicago’s interests would dominate. On balance, I think both Chicago and its suburbs should fear the creation of an agency so huge that it will be hard to bring its resources to bear on the actual problems of each community.

Another objection to consolidation: no local ownership. With a mega-regional agency, a neighborhood asking for a route or schedule modification will be silenced no matter how loud they shout. They’d be blowing in the wind.

As a Chicago area resident for over 40 years, I propose that the missing element in Chicago’s inefficient public transportation system is highway-capable, weather and road protected #ThinMobility – defined as vehicles one meter wide with supporting lane and parking space access. Suburban bus operators Pace, which already offers shared vans to be stored at private residences, would be the best current agency to provide the service.

Very thoughtful piece, which should be helpful guidance to the policy-makers who are under justifiable pressure to “do something” about a status quo that is sub-optimal. A third player is the RTA, which (sort of) sits above both your clients CTA and Pace as well as Metra, a fourth player which is the suburban passenger rail provider. (And the RTA is NOT the MPO!) I agree with you that mega-consolidation of them all is likely to create more complexity than benefits. One place to look for better clarity of roles is to better define what the RTA is or isn’t, how it relates to the MPO, and to instill some regional spending and operational standards based on the social factors you suggest. Again, thank you for a very insightful post.

What you say makes sense- if you are only talking about Pace & CTA. Metra is the agency that has the least efficient use of resources and the most inequitable service design. Modernizing Metra to have all day frequent service, infill stations, and fares and schedules integrated with other modes would transform many parts of both the city and suburbs (especially South Side communities) into places with effective transit. Chicago and Chicagoland are far too big and too congested to cross with a bus in a timely fashion, no matter how much lane priortization you can accomplish, so rails are necessary to get any transit mobility approaching that of a car. And similarly it is too spread out for trains to provide adequate coverage without connecting buses (or a massive uptake in bicycling). If there’s a way to get Metra to get with the program and work with the other agencies to improve meaningful access, then great there’s much less reason to consolidate. That paradigm doesn’t seem to be happening, though, so forcing it to via a merger might be the path forward.

Would it make sense to keep CTA and Pace separate, but consolidate Metra with buses for better coordination? I could see combining most of Metro with Pace, and combining the Metra Electric with CTA.

*Metra

Great explanation of the arguments against consolidation. Funding and clear, realistic, and integrated (where appropriate) goals for CTA, Pace, and Metra are key.

Thinking of cities and transit agencies in San Francisco and Chicago, other cities (ie. Dallas) should ponder their own municipal transit agencies. With political tension between the suburbs and central city, we have an agency struggling to meet any of its goals.

“Chicago has a large low-income and racial minority population living in especially remote parts of the city, often at low densities”

The data, including from your post, do not support this.

First, your population map states ‘The rest of the city features “pie slices”’. The geometric definition of a circle is equal distance from a point, so if the racial makeup is pie slices (segments of a circle) then by definition minorities do not live in more remote parts, instead they live equally close, since each slice contains neighborhoods near and far from downtown. Douglas/Bronzeville on the southside (largely Black) are just as far from the Loop as Lincoln Park/Lake View on the northside (largely White). Black people at the end of the Blue and Green Lines in Austin are no farther from the Loop than White people along the Brown Line in Albany Park – in fact their travel time is less because the Blue/Green run straight while the Brown zig zags.

Nowhere in Chicago is “low” density. Two thirds of the neighborhoods have greater than 10k pop/sqmi, the threshold identified by Zupan and Pushkarev as supporting useful transit. Most of the others are between 6-10k/sqmi, with only a handful that are not clearly urban. Chicago as a whole is 12k/sqmi.

While some areas on the south side that are lower density and largely Black, this is an artifact of Chicago’s asymmetric borders. West Pullman, largely Black, is 14mi south of the Loop with a density of ~7300/sqmi. Wilmette, largely White, is 14mi north of the Loop with a density of ~5200/sqmi. Franklin Park, largely White, is 14mi west of the Loop with a density of ~3900. W. Pullman is inside Chicago borders while the other two are not, so one could technically say lower density ‘areas of Chicago’ are Black, but in the metro area Black neighborhoods are neither farther nor less dense than White neighborhoods in different directions.

Further, the lowest parts of Chicago (S. Deering, Hegewisch, etc.) are industrial parks with few residents – the five far southeast neighborhoods have only about 1% of the city’s population, not a “large population”.

Finally, your dot map is extremely misleading for transit access. It only shows CTA subway lines, making the south side look underserved. In fact it is blanketed by the Metra Electric and Rock Island Districts – 35 stations plus one on the Indiana South Shore Line. The Metra Electric District is the only one with electric power and high platform level boarding and has the most runs per day – the lower pollution, greater handicap access and higher frequency means the Black residents of South Chicago are BETTER served by commuter rail than White communities at a similar distance, such as Wilmette on the UP North District or Franklin Park on the Milwaukee West District.

The dot map is a Census Bureau product. The Census people could really take a clue from Jarrett and make their maps more intuitive and useful like he did with transit maps…. They could change the land background color from white to light green. This would enable them to use dots with intuitive colors: yellow for Asian, black for Black, brown for Hispanic, and white for White. I know this is a technically non-transit-related nitpick, but it would still make sense.

The dot map is not a Census product. It uses census data, but the various dot maps are produced by independent organizations (Univ. of Virginia, CNN, ESRI, etc.). I presume the use of non-“intuitive” racial colors is deliberate to avoid association with racial stereotypes/slurs sometimes associated with those colors.

Thanks for the correction. I’ve seen these maps elsewhere and they always reference census data, so I unfairly presumed they were Census products.

Thank you for showing me I was wrong when I said “ridership is natural equity” in the past. In most cities I’ve lived in, it would be. However, I can see how exceptions like the far South Side of Chicago exist.

From my perspective, a big advantage of consolidation is coordination. How well are Pace, CTA, and Metra coordinated? I would probably go “all-in” on saying they are not at all coordinated.

In terms of being “too big” to be coordinated, Translink in Vancouver, BC is one of the largest transit agencies in North America and yet it still manages to provide appropriate levels of service in all areas of the metropolitan region from inner city Vancouver to Langley. But yes I would not expect any agency to want consolidation because if Metra, CTA, and Pace consolidated there could only be one CEO instead of three.

As I posted elsewhere, a regionl transit agency can be less responsive to the needs of some areas it oversees–think NYMTA. That said the fiscal issue in Chicago is, IMHO, a aspect of both class and race prejudice over the last century. The mainline RR commuter services gradually closed local stations (entire routes) in response to shifting population profiles. What we call MED today ysed to have a very dense market in the South Shore neighborhood before 1960–resulting in very frequent rush hour ‘specials’ (their name for very limited stop schedules), half hourly baseday and evening service. Thje Illinois Central was an electronic fare gate pioneer inthe late 60s. The take over by RTA/Metra resulted in degraded schedules, a return to 19th century fare collection, and cratering ridership. Early this century transit advocates began lobbying to have MED (and the Rock Island District) fare integrated into CTA. While a partial discount ‘pilot was in effect briefly, turf defense has triumphed Given that ALL of transiy in Illinois will need increased state support, maybe the Legislature can mandate more cooperation as a condition of bailout.

What any MSA/CSA needs is one organization responsible for the flat rate fares that transfer between systems so that people who ride a lot can just ride without worries about transfers or paying a lot of money just because their route crosses two operators. This organization is also responsible for creating time transfers between operators (they may sometimes be forced to agree to not have them just because it isn’t possible, but you cannot miss a timed transfer without their approval – and they can also lobby for fixing physical issues that make them impossible)

However as you say, smaller units often do have good reason to want control over their own transit system. The compromise between subsidy, coverage, and ridership often gets different answers in different places and this isn’t always bad.

The map showing the frequencies of Pace’s bus routes is really informative. Can you share a similar map pf CTA’s bus frequencies (as a PNG)?

If the three agencies consolidated, going from three to one CEO is about all you’ll get. At every other level of a consolidated agency, you’ll mostly need the same amount of people to run the system. Both frontline and behind the scene workers. Any redundant positions are likely to be lower skilled positions with minimal impacts to the budget. So consolidate, rebrand tens of thousands of vehicles and signs, years of internal system integration, multiple unions to deal with, and eventual service cuts in the city to placate suburban leaders. It’s not worth it.