This is so important! Crosspost of an essay by Daniel Kay Hertz, from the excellent City Observatory blog, where it was titled "Urban residents aren't abandoning buses: buses are abandoning them."

“Pity the poor city bus,” writes Jacob Anbinder in an interesting essay at The Century Foundation’s website. Anbinder brings some of his own data to a finding that’s been bouncing around the web for a while: that even as American subways and light rail systems experience a renaissance across the country, bus ridership has been falling nationally since the start of the Great Recession.

But it’s not buses that are being abandoned. It’s bus riders.

The drop in bus ridership over the last several years has been mirrored by a decline in bus service, even as transit agencies have managed to resume increasing frequency and hours on all types of rail lines – heavy, light, and commuter.* (In this post, "service" means vehicle revenue miles – literally, multiplying a city's bus or rail vehicles by the number of miles they run on their routes.) After a post-recession low in 2011, by 2013 rail service had increased by over 4% nationally in urban areas of at least one million people. Light rail in particular has continued its decade-plus boom, with a service increase of more than 12% in just two years. By contrast, bus service – which already took a heavier hit in the first years of the recession – was cut an additional 5.8%.

And it turns out that when you disaggregate the national data by urban area, there’s a very tight relationship between places that cut bus service between 2000 and 2013 and those that saw the largest drops in ridership. If you live in a city where bus service has been increased, it’s likely that your city has actually grown its bus ridership, despite the national trends. In other words, the problem doesn't seem to be that bus riders are deciding they’d rather just walk, bike, or take their city’s new light rail line. It’s that too many cities are cutting bus service to the point that people are giving up on them.

Admittedly, this is a crude way to demonstrate a very complicated relationship. To rigorously test the impact of bus service on ridership, you’d want to take into account all sorts of other things: the presence of other transit services; population density; gas prices; demographics; and so on.

Fortunately, we don't have to do that, because researchers at San Jose State University’s Mineta Transportation Institute just did it for us. And they found that even if you control for those other factors, service levels are still the number one predictor of bus ridership.

Still, I can imagine two big objections to the idea that cuts to bus operations are behind ridership declines. First, a lot of cities have opened new rail lines since 2000 – many of which, if not most, replaced heavily-trafficked bus routes. In those cases, cities are adding rail service and reducing bus service, but it obviously wouldn’t be right to say that those bus riders are being abandoned.

But while that has surely happened in some places, it just doesn’t match the overall data. Rail service, including new lines, has been booming since long before the recession – but up until about 2009, bus service was growing, too, or at least holding steady. If rail expansions were driving bus cuts, you’d expect to see those cuts all the way back to the beginning of the data. But you don’t. Instead, cuts to bus routes appear right as transit funding was hit hard by the recession.

Second, you might argue that service and ridership are linked, but the other way around: as ridership declines, agencies cut back on hours and frequency to match demand. Teasing out which way the causation runs would be difficult – and the answer would almost certainly include at least some examples in both directions. One quick-and-dirty way to get an idea, though, is to compare ridership changes from one year to service changes in the next year. If agencies cut service because of earlier ridership declines, then you’d expect to see that places with larger drops in ridership in “Year One” tend to be the places with larger cuts to service in “Year Two.”

But, again, they don’t. In fact, just 3% of the variation in service cuts is explained by ridership changes from the year before.

So while that’s hardly ironclad – and I look forward to further research that sheds more light on this problem – it does appear that a major part of the divergence in bus and rail ridership is a result of a divergence in bus and rail service: since the recession, transit agencies have cut bus service year after year, while returning service to rail relatively quickly.

Why did they do that? I don’t know. But I can speculate that it has something to do with the fact that bus transit supporters are not always the same kinds of people as rail transit supporters. Even though more people take buses than trains in nearly every metropolitan area in the country, train riders, on average, tend to be wealthier and whiter. Not only that, but many civic and business leaders who don’t use transit at all are heavily invested in rail service as an economic development catalyst for central city neighborhoods. In other words, rail tends to have a more politically powerful constituency behind it than buses.

As a result, when the recession blew a hole in transit budgets around the country, it may have been politically easier for local governments to fill those holes by sustaining cuts to bus lines, rather than rail.

To be clear, the problem here has nothing to do with whether transit agencies are running more services that are rubber-on-asphalt or steel-on-tracks. As Jarrett Walker has eloquently argued, the technology used by a particular line matters far less than the quality of service: how often it runs, how quickly, for how much of the day.

But there are at least two problems here. First, because of the spread-out nature of even relatively dense American cities, it will be a very, very long time before rail transit can connect truly large numbers of people to large numbers of jobs and amenities. When Minneapolis opened the 12-mile Blue Line light rail in 2004, for example, it was a major step forward for Twin Cities transit – but still, only 2% of the region’s population lived close enough to walk to one of the stations. For everyone else, transit still meant taking the bus, even if they were taking the bus to a train station.

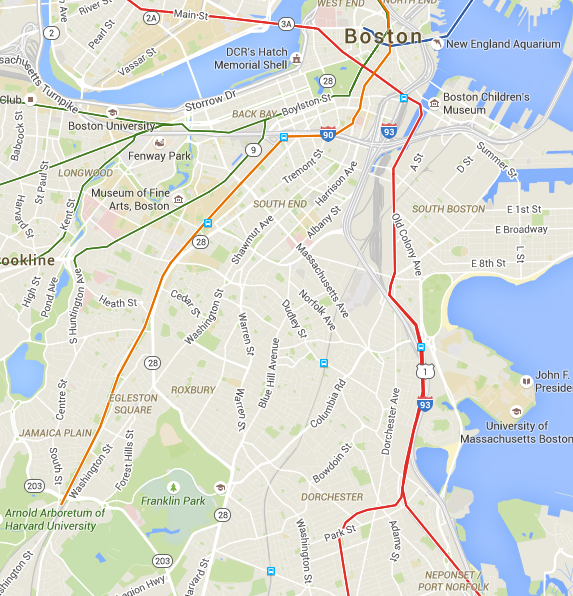

And even in places with well-developed rail networks, those systems are usually oriented to serve downtown commuters. Especially in outer neighborhoods, crosstown trips in places like Chicago, Boston, or DC are heavily reliant on buses. Abandoning buses means abandoning those trips, and the people who depend on them.

Boston's T reaches both Dorchester and Jamaica Plain, but a bus is by far the easiest way to get from one to the other on transit. Credit: Google Maps

Boston's T reaches both Dorchester and Jamaica Plain, but a bus is by far the easiest way to get from one to the other on transit. Credit: Google Maps

Second, there are serious equity issues with shifting resources from bus to rail – again, not because of anything inherent to those technologies, but simply because of who happens to use them in modern American cities. In most cases, shifting funding from bus to rail means shifting funding from services disproportionately used by lower-income people to ones with with a stronger middle- and upper-middle-class constituency. And while transit ought to be viewed as much more than just a service for the poor, we can’t ignore the equity impacts of transit policy.

In light of all this, we have to stop talking about America’s bus woes as a ridership problem. All the evidence suggests that when service is strong, and buses are a reliable way to get to work, school, or the grocery store, people will take them. Instead, the problem is that fewer and fewer people have access to that kind of strong bus line. If we care about ridership, we need to restore and enhance the kind of transit services that people can rely on.

* “Heavy rail” includes traditional subways and elevated trains found in cities like New York, Washington, and Chicago. “Light rail” includes many newer systems, with smaller train sets that are sometimes designed to run on streets as well as in their own right of way. Rail lines in Seattle, the Twin Cities, and Dallas are typical of light rail. “Commuter rail” services generally reach from central business districts far out into the suburbs, and are meant almost exclusively for peak-hour workers.