In the last post I took on the problem of poor data analysis in transit journalism, specifically how easy it is to create totally arbitrary stories out of performance trends. This post is about another routine mistake in transit journalism, which is to make false assumptions about what transit investments are trying to do. The most common example is to assume that short-term ridership is the only valid measure of transit’s success.

For this series, I’m taking examples from an example-rich Los Angeles Times article on the alleged “accelerating” decline of transit ridership in Los Angeles. The article, by Laura Nelson and Dan Weikel, is provoking a lot of commentary, but it’s not unusual in the assumptions it’s making.

Here’s the lede again:

For almost a decade, transit ridership has declined across Southern California despite enormous and costly efforts by top transportation officials to entice people out of their cars and onto buses and trains.

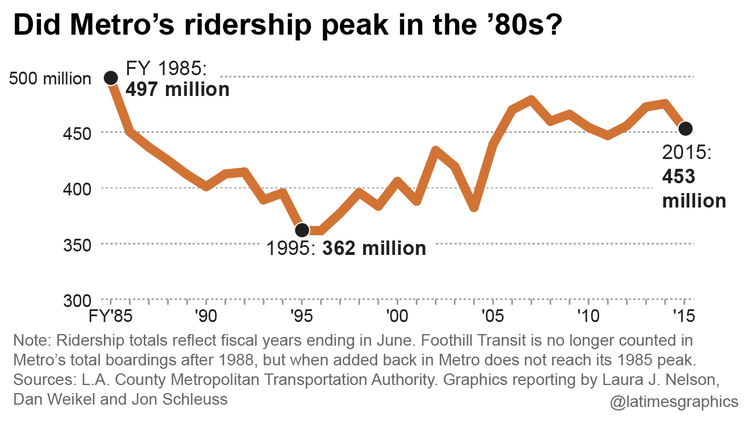

The Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority, the region’s largest carrier, lost more than 10% of its boardings from 2006 to 2015, a decline that appears to be accelerating. Despite a $9-billion investment in new light rail and subway lines, Metro now has fewer boardings than it did three decades ago, when buses were the county’s only transit option.

Long Term Infrastructure Is Not About Short Term Ridership

Here and throughout the article, Nelson and Weikel insistently pair the ridership drop with the $9 billion cost of an infrastructure investment program, giving the reader the impression that they must be connected.

This is like saying that your crops failed because you didn’t have a harvest the day after you planted them.

In this case, the “$9 billion investment” in infrastructure has nothing to do with the short term ridership being discussed here. The rapid transit program is designed for long-term ridership growth and city-shaping effects. One of the key things they do, for example, is make denser development viable, which enables more people to live and work where transit is excellent and therefore rely on it more. Nelson and Weikel quote Metro’s CEO making this point, but doesn’t really explain why long-term investment works.

So how would you assess the value of these lines? You’d look not just at ridership but at what’s happening in real estate development along them. You’d look at what the trends are in demand for housing and jobs near good transit, and extrapolate to show the benefits — for livability and in terms of long-term ridership potential — of meeting that demand. And you’d see how similar investments in similar places have paid off in the past.

In a Tweet yesterday, Nelson said:

The ‘it’s too early to evaluate’ response (a favorite of Metro’s) has always struck me as self-inoculating.”

Yes, it can strike me that way too, which is why great transit agencies put a lot of effort into explaining this issue. But that doesn’t make it wrong.

It takes a while, but great transit investments (and they’re not all great) do pay off when they’re done well. And when they’re not done well, it’s not ridership that tells you this, but rather contradictions in the plan — like putting stations in places where dense development is illegal or impossible, or building in too many sources of delay while claiming that the line will be fast and reliable.

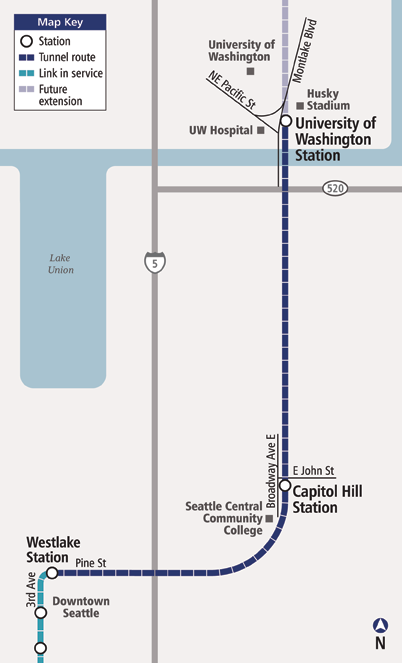

It’s easy for people to take pot-shots at transit projects by arbitrarily focusing on one outcome. In a recent Seattle Times panel I was on recently, for example, Brian Mistele of the traffic analysis firm Inrix repeatedly criticized a Seattle area light rail line for not reducing congestion on the adjacent freeway, as though that were its purpose. Another common example of this mistake is to criticize bus services for low ridership without asking if ridership is even their goal; many bus services exist for non-ridership purposes.

So remember: If you’re going to imply that something is failing, you have to understand what it’s actually trying to do, and show it’s failing at that.

Compare Ridership to the Service Offered

A broader point here is that ridership, and especially ridership trends, are meaningless unless they are compared to the service offered to achieve them. This article gives the appearance of doing that by making a false comparison between short term ridership and long term investments. This echoes the common fallacy that transit ridership is generated by infrastructure.

In fact, transit ridership comes from operating service. Infrastructure is mostly a way to make that service more efficient and attractive, but its impact on ridership is indirect, while the impact of service is direct.

So the most important frame of reference for ridership is the quantity of service being operated, not capital dollars being spent. This is why the article (and transit agency databases in general) should be showing productivity (ridership per unit of service provided.) This “bang for buck” measure is the only way to tell whether transit is succeeding given how much service is being offered.

he dense Capitol Hill neighborhood, opens today. And if you vaguely associate Seattle with vast

he dense Capitol Hill neighborhood, opens today. And if you vaguely associate Seattle with vast