My friend David Bragdon (the former head of TransitCenter and former elected head of the Portland area’s regional government) has a good, through article at Eno on the problem facing rural bus service, generally defined as services more than 50 miles long not primarily intended for commuting. He’s not focused on links between big cities, which have air and (sometimes) rail options, and where bus services are often still profitable. The concern is all the smaller towns that had commercial bus service 50 years ago, but generally no longer do. These towns have lots of people who need to get to nearby bigger towns for medical services, errands, shopping, and other needs that they can’t get locally. I call these services “rural intertown” but note that the difficulty of describing this category is probably part of why it’s so neglected.

My friend David Bragdon (the former head of TransitCenter and former elected head of the Portland area’s regional government) has a good, through article at Eno on the problem facing rural bus service, generally defined as services more than 50 miles long not primarily intended for commuting. He’s not focused on links between big cities, which have air and (sometimes) rail options, and where bus services are often still profitable. The concern is all the smaller towns that had commercial bus service 50 years ago, but generally no longer do. These towns have lots of people who need to get to nearby bigger towns for medical services, errands, shopping, and other needs that they can’t get locally. I call these services “rural intertown” but note that the difficulty of describing this category is probably part of why it’s so neglected.

This should be not be a left-right issue, and mostly isn’t. Congress, with ample support from rural Republican lawmakers, has long supported a Federal funding program called 5311(f) which provides funding for needed bus links that no longer exist commercially. But this funding is basically a grant to the state Departments of Transportation, which can spend it on whatever bus service they like. Bragdon observes that some states are doing great things with this money, creating statewide lifeline networks focused on towns that would otherwise be abandoned, but that other states often just give the money to private carriers like Greyhound, without even checking their claims that the subsidy is needed to keep some service running. “In short,” Bragdon writes, “many state DOTs spend a lot of money, particularly on highways but to some extent on buses, without explaining what they’re trying to achieve.”

Bragdon is arguing, in short, that like urban transit, intercity lifeline service should be planned. At its root, planning is the process of identifying goals and making sure that a plan of action actually meets them cost-effectively. I agree, and anyone interested in this challenge should read his article.

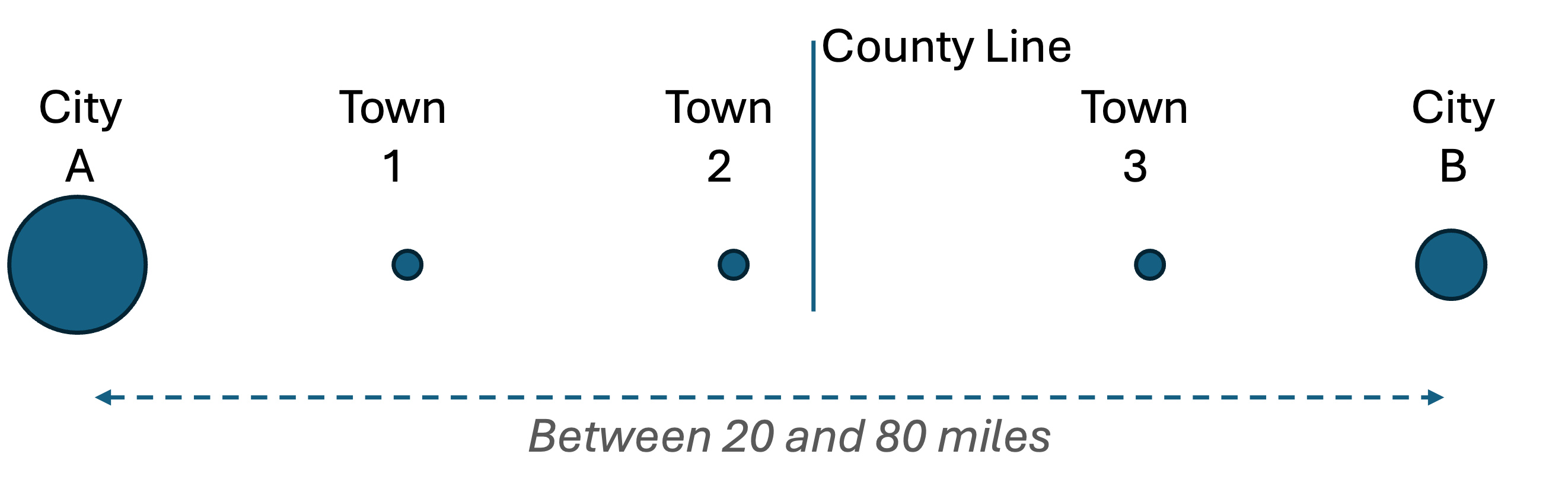

There’s an overlapping problem, though, when we’re talking about shorter corridors (under 80 miles or so) and there are enough towns along the way to justify service every day and several times a day. Here, the obstacle may be the county-level organization of transit, which gives no agency the job of serving the entire corridor. I addressed that in the next post.