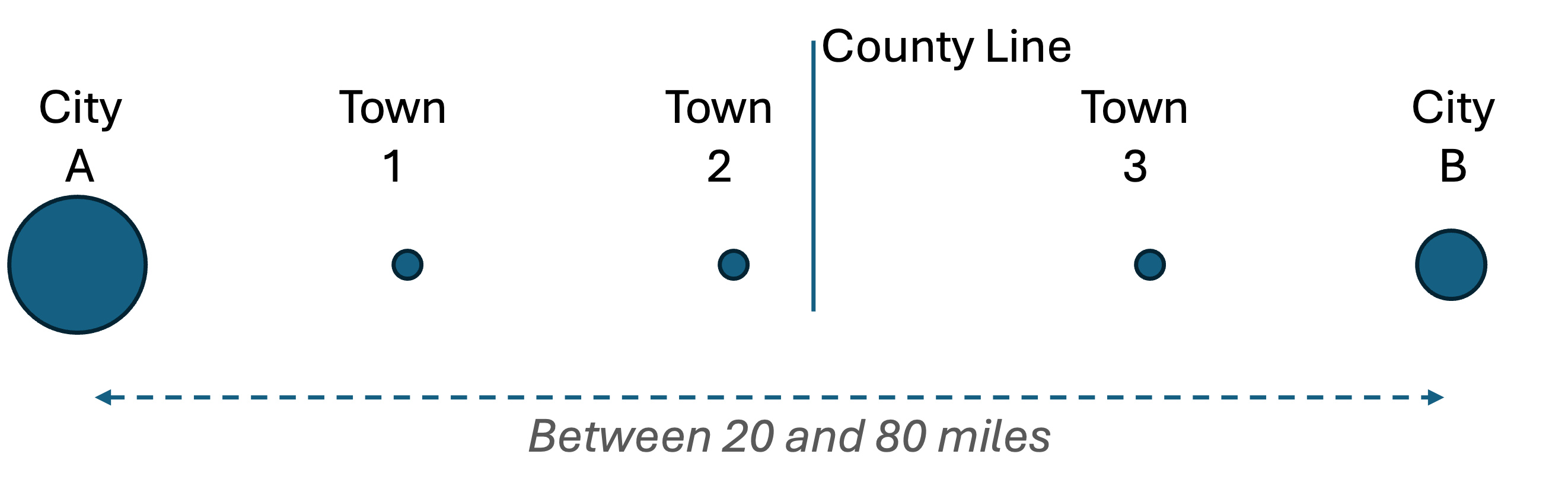

In the US, public transit is often organized at the county level, so the service ends where the county does. There are countless situations like this, where two significant cities are 20-80 miles apart with a county line separating them:

If transit is provided by county-level agencies, the service in this situation looks like this:

The two transit agencies probably have the best of intentions. They’ve probably worked together to find a common stop in Town 2 where they meet. They may or may not have planned the schedules so that the buses meet and people can connect between them to travel to the big cities. But even if they’ve done that, the end-to-end connection is a gratuitous hassle. You have to get off one bus and onto another, and worse, there’s a well-above-zero risk that you’ll be stranded if an arriving bus is late.

The better service, and the greater access to opportunity, arises from doing this:

If this corridor is important enough, the county level agencies may have merged to resolve this problem, but usually they haven’t. Mostly I’m talking about cases where City A and City B are the centers of counties that have numerous internal travel demands, including to other towns in other directions, so that this particular corridor isn’t the most important thing they do. In fact, it may seem rather peripheral to them. What’s more, if they are just running to a small town near the county line, the ridership probably isn’t that great, which means that there’s not much impetus to improve things.

So if the county-level agencies aren’t able to combine their services, the state Department of Transportation should look at this situation and see if they can use their leverage to create a solution. This could mean leaning on the county-level agencies to solve the problem, or it could mean creating (or enhancing) a state intercity bus product to handle these situations.

None of this is easy. Like all organizations, county level transit operations may feel threatened by the loss of role, importance, or access to funding. They may be bound up with different labor contracts, which can be especially hard to reform. A state bus route taking over some local services in the county will need fare integration with the rest of the local system. But states that want great statewide transit networks need to care about this issue. A lot of service is already tied up in these county-level rural links, and they won’t always run the most efficient patterns if they are trapped by county lines.

One of the wisest approaches to transit planning and organization I’ve read is to treat transit planning as a science and transit operations as an art.

The planning aspects of transit, like setting fares, the engineering and construction of rail lines, building schedules, mapmaking, accounting and finance, etc., are generally identical problems and can and should be done at a high level organization.

Germany does this through the Verkehrsverbund, where a high-level organization does the financing, planning, schedule coordination and marketing, while devolving operations and maintenance to local operators. (In Europe, one big difference to transit operations is that the service provider is a private company holding a tender; in the U.S., transit workers tend to be directly employed by government).

Operations are more “art” because conditions vary widely across operating environments — a higher ridership service in the center of town also poses more challenges, like bus bunching, overcrowding and unreliability (as ridership goes up, schedule adherence goes down). As Jarrett mentions, labor relations also play a large role. Harmonizing contracts leads to painful conversations or work stoppages that no one really wants, so these conversations are avoided. Also, there is a productivity issue that stems from the customary nature of transit workers bidding on work based on seniority. A high-seniority bus driver tends to bid on the lowest ridership routes. Inexperienced drivers are stuck doing the most challenging, high ridership routes. (High-seniority drivers are paid more to move fewer people; low-seniority drivers are paid less but move more people). This dynamic tends to make coverage services untenable.

These operational challenges are more suited to devolution to help contain costs and improve reliability.

There are far too few of these organizations in the U.S., but need to be tried more. Portland’s Tri-Met is generally a pure transit operator, but if its planning and administration were done by the Metro government, it could be more in the mold of what Germany has.

No one thinks of Maricopa County’s transit service in favorable terms, but Valley Metro comes close to the Verkehrsverbund. There’s a single brand identity for the transit services and you’d think of Valley Metro as a single entity because the fares are the same, all the schedules are listed in one place, and there’s one call center for transit information. However, at the operations level, the cities (Phoenix and its suburbs are all massive, both in terms of population and area) are responsible for taxation and funding of service and each city contracts out operations — it’s some mix of Transdev and MV, Scottsdale going with someone called RTW, and Glendale hiring its drivers in-house.

Thank you for mentioning an American transit system that works similar to a Verkehrsverbund. That makes it easier for we in America to understand what that is.

I would also like to comment on the seniority issue. Maybe operator pay should be on a two-axis grid, with one axis being seniority and the other being ridership and other challenges. I also support “hazard pay” for routes where problematic passenger behavior is more of an issue.

We have a pay differential that pays drivers working second shift a little more than first shift. Most senior drivers want first shift, but second shift has a higher proportion of customer bad behavior. This helps shift some experience to the second shift. In terms of spreading experience out on all routes, none of our driver picks drive the same route every day. They all have at least two routes they drive, depending on day of the week, and some more. Internal surveys show the majority of our drivers prefer this variety anyway.

Not all transit in Europe is tendered out, public transit can also be directly awarded to operates wholly owned by the municipal, state or federal entities. In the German speaking world that is very commonly done for city-level bus and rail service, less so for regional busses.

Germany also has a weird model grandfather in where commercially self sufficient regional bus lines can be operated by the operators with minimal supervision of the regional government. A large part of the “self-sufficiency” in these cases stems from fees payed by the government for transportation of students or free passed for the poor and jobless, so it’s a bit of a misnomer. It usually only happens in rural regions outside of well working Verkersverbünde and fortunately has been massively declining in the last years.

Great piece Jarrett! And I agree completely – the “forced transfer” issue is always a brake on the potential for additional ridership.

But one thing that needs to be mentioned, in my experience, is the funding mechanism. I have worked with many agencies over the years, and many of the planners wish to create combined routes with a neighbor or just simply extend their service past some political border. But if the jurisdiction to which they wish to connect with doesn’t “pay in” to the existing system (i.e., “has no skin the game”), or if it does not levy taxes and fund their own system (or share of the route) to the same extent or in the same manner, then the agency is simply not allowed to operate there, and riders suffer. And in too many states the state government simply doesn’t have the mechanism to step in and help – so I totally agree with your contention that they should in such a situation.

I once was working for a system where a portion of the local sales tax in a certain county provided the lion’s share of transit funding. A small community just on the other side of the county line was asking for service to be extended there (literally just about one mile), to a retail area that also happened to be near a freeway interchange, so not only shoppers but also employment would be served. I had both a policymaker and a local merchant ask me why they should pay to “drive folks out of the county to shop where the taxes were lower”.

You can’t make this stuff up.

Yes, the desire of local governments to use transit to manipulate where people can shop is very common! And if the funding is based on a sales tax or VAT they have a little bit of a point, but still it’s aggravating.

Rural bus service in Minnesota has this problem big time. And it’s made worse by the fact that most rural transit is dial-a-ride. Also, service often ends exactly at the county line, and often the systems don’t accept the county line sign at the side of the road as a legitimate origin or destination.

It’s not just rural routes. There are a lot of cases where suburban bus service arbitrarily ends at the county line too.

It’s one of the many reasons we need to seriously reconsider the current structure of local government in the US. We’d be better served by the German model of multilayered regional government

Before the Verkehrsverbund concept migrated from Hamburg, the Ruhr municipal tram systems ran pools of paired lines. Every other car would be from one city or the other. Fare collection changed at the city lines. Most striking was the Duisburg Muelheim pair, because of differing gauges.The paired segment used a three-rail track. There are many solutions out there, waiting for the willing to act.

Tri-Met ran into the county line issue early in its life when it purchased Tualatin Valley Stages, which included a line to Newberg and McMinnville in Yamhill County. Unfortunately, it had to cut service on US99W back to Rex and Sherwood. Communities that had Southern Pacific commuter service at one time were left with three Greyhound trips a day, scheduled to discourage commuting.

>> So if the county-level agencies aren’t able to combine their services, the state Department of Transportation should look at this situation and see if they can use their leverage to create a solution. This could mean leaning on the county-level agencies to solve the problem, or it could mean creating (or enhancing) a state intercity bus product to handle these situations.

Exactly. This is the ideal model in my opinion. Every state should have an agency tasked with improving interagency/intercounty service. This means running their own buses (or trains) in some cases but in others it means forcing the two agencies to sit down and work out the various issues. As mentioned above a lot of routing is terrible simply because it crosses the county line. With a little bit of effort they could really help the folks in the other county but since it isn’t their constituents, they don’t bother. The budget for such a state agency like this would probably be relatively small (much smaller than an urban county would spend on their buses) but big enough to do a decent job. Also mentioned above — this problem often occurs in the suburbs — not just rural areas.

I’d be happy if Pennsylvania did more of this. Far too often in PA, there is no transfer point between adjacent systems at all.

For example, imagine the diagram was:

City A: Philadelphia

Town 2: Pottstown, less than a mile from the county line

Town 3: Birdsboro, 9 miles from Pottstown

City B: Reading

SEPTA bus route 93 ends in Pottstown. But Reading’s bus route 8 doesn’t begin until Birdsboro. An 8 mile ish gap prevents anyone from crossing the Berks-Montgomery county line at all.

Same situation exists on the other side between Reading (Berks Co) and Lancaster (Lancaster Co)… and that’s even more egregious since the same transit authority (SCPTA) technically owns and operates both formerly-independent BARTA (Reading) and RRTA (Lancaster). Nothing stops them from connecting their 2 operating divisions together except apathy. Sad because it means Reading – the fifth largest city in the state – has no connection to any rail in Lancaster or in suburban Philly.

https://www.sctapa.com/

This is a problem with departments in France as well. And more and more at the boundary of Greater London where the surrounding county councils are increasingly starved of funding and unable to contribute.

This is a problem in many places outwith the USA. The following example in my local area in England illustrates this issue very well.

In north west England, Greater Manchester inaugurated its new Bee network for bus services recently, with the final part of the implementation starting on 5th January 2025. With effect from this date, Transport for Greater Manchester (TfGM) control all the public bus services running within its area. TfGM couldn’t reach agreement with the neighbouring borough of Warrington which runs its own municipal bus service, so the through interurban bus service from Warrington to the neighbouring town of Altrincham (where I live) within Greater Manchester was cut from this date into 2 segments at the intermediate small town of Lymm.

The Altrincham-Lymm segment is now provided by a different operator and runs less frequently and not at all on Sundays or in the evening. Connections with the remaining Warrington-Lymm segment, still provided daily at the previous frequency by Warrington Borough Transport, are poor and not guaranteed.

@daodao This is regrettable. I think the 125 Preston to Bolton was allowed to be “honorary” Bee Network within Greater Manchester, but this is itself a long-standing deed.

split. While anyone actually going from Preston or Chorley to Manchester will naturally get the train, this is cold comfort for anyone else crossing Bolton.

Cross boundary bus service is likely to become a bigger issue in the UK as the bigger urban areas take back control of bus services through franchising of their networks. The example of Warrington, a sizeable town with its own municipal bus company that previously ran through service into Greater Manchester has already been mentioned. In fact Warrington is also close to the Merseyside City Region (centered on the city of Liverpool). Interesting Warrington’s Own Buses (the municipal company) has adopted a yellow livery that hints of neighbouring Merseyside’s new “Metro” branding, and Greater Manchester’s Bee Network. Perhaps future integration with these two neighbouring conurbations is to come.

Elsewhere in the UK commercial bus companies can ignore administrative boundaries and operate services linking larger settlements with their rural and exurban hinterlands.