While you’ve heard plenty about big US agencies facing a “fiscal cliff,” some agencies are doing well and expanding their offerings as their staffing permits. That includes Portland and Dallas, where we’ve been working, but here’s a similar story from a smaller agency in an outrageously beautiful place.

While you’ve heard plenty about big US agencies facing a “fiscal cliff,” some agencies are doing well and expanding their offerings as their staffing permits. That includes Portland and Dallas, where we’ve been working, but here’s a similar story from a smaller agency in an outrageously beautiful place.

Santa Cruz County, just south of the San Francisco Bay Area, is known for its beautiful beaches, towering redwoods, college-town ambience, and expensive housing, but the county also contains Watsonville, on the edge of the agricultural Salinas Valley, which has cheaper housing and is over 80% Hispanic or Latino/a. The University of California at Santa Cruz (UCSC) generates huge demand to its hilltop campus at the west end of the region, but Watsonville generates strong demand for travel both locally and to jobs in Santa Cruz. Meanwhile, the City of Santa Cruz is trying to encourage denser housing along frequent transit corridors in order to address their problems of housing affordability.

Like many US agencies, Santa Cruz Metro had to make cuts during the pandemic to match the service to their shortage of bus drivers. In the last year, though, the pace of hiring has picked up, and the agency can do its first substantial expansion. They asked us to analyze the network and develop some concepts for improvement. We drafted a couple of alternatives, and had a public conversation about them. Finally, last Friday, the agency’s Board adopted a Phase 1 restructuring plan. By then, it turned out, hiring had gone even better than expected and some hard choices that we had feared would have to be made turned out not to be necessary.

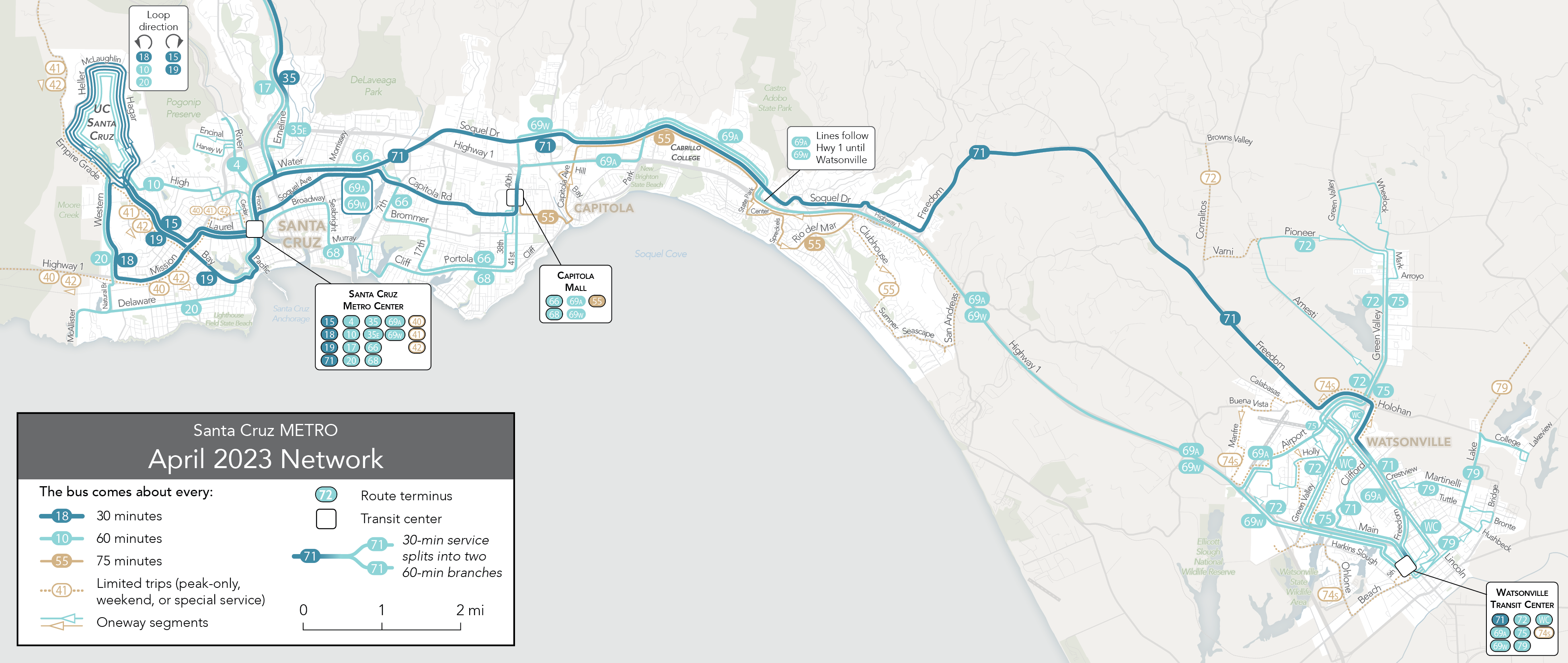

Phase 1, now scheduled for implementation this December, will change the network completely. It currently looks like this. (As always, click maps to enlarge and sharpen.)

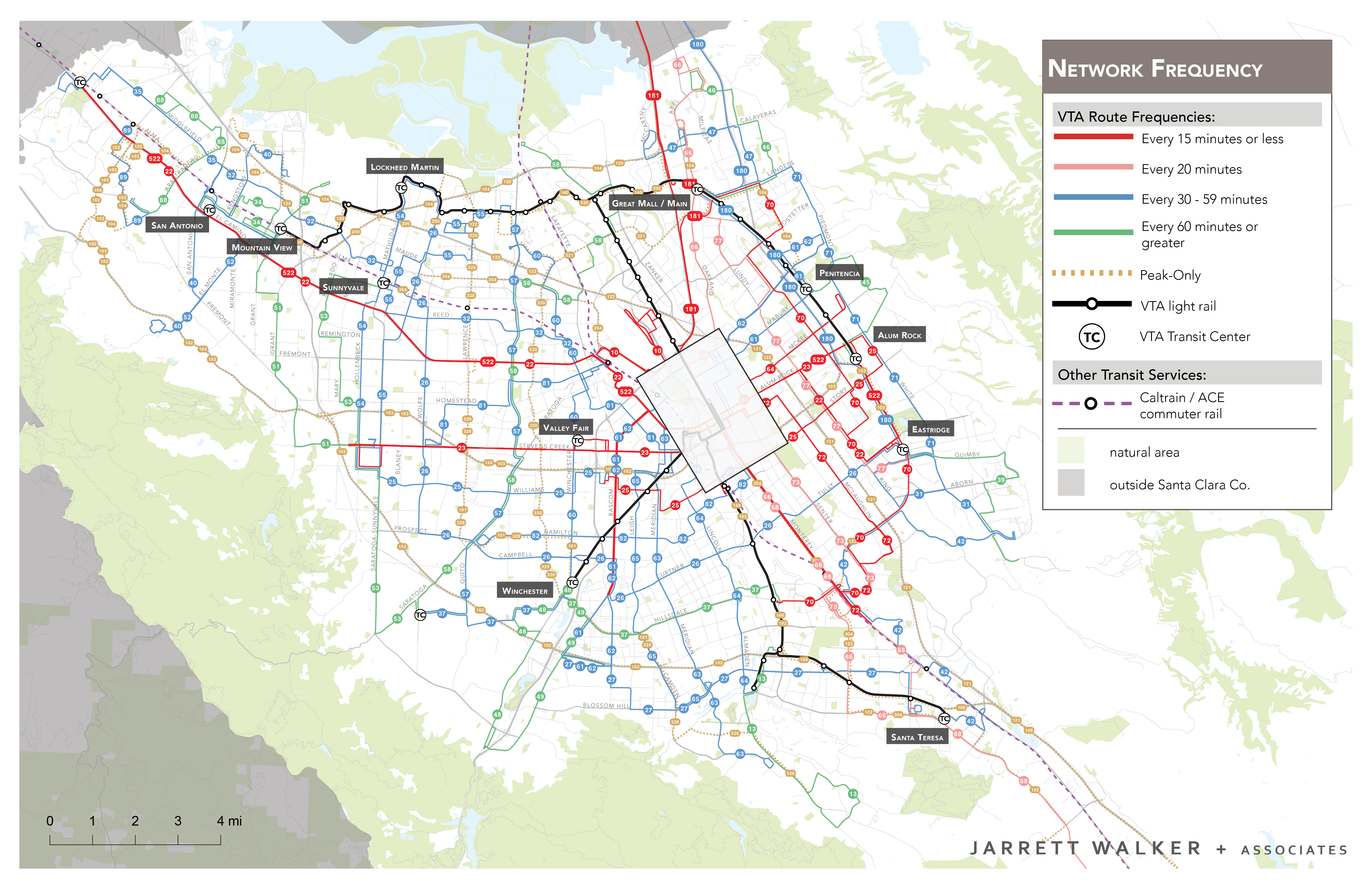

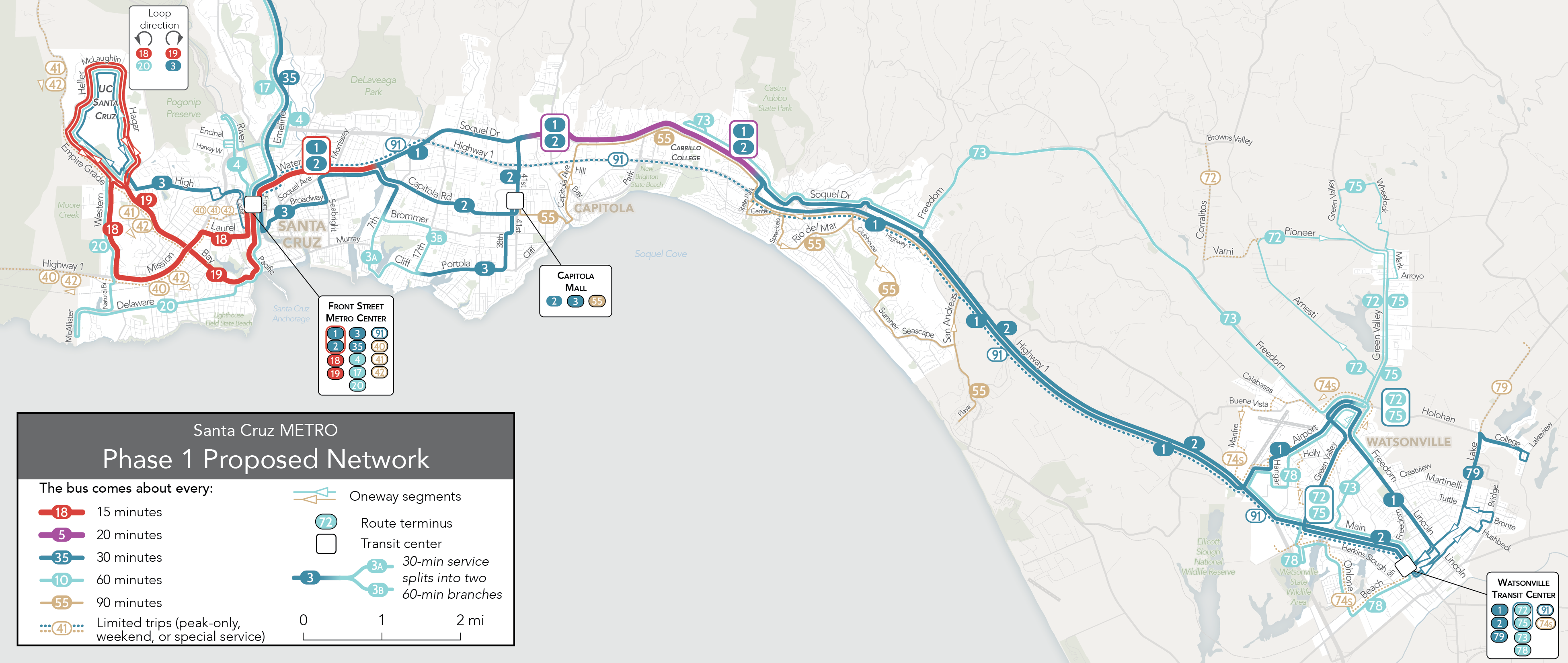

Starting in December it will look like this.

Look at the legend! As always, colors on these maps represent frequency, and that’s fundamental to understanding how this network is better than the old one.

The existing system has no service running better than every 30 minutes, but it also has no timed connections, so waits are long, not just for your initial bus but also for the bus you may be connecting to. The redesign increases frequencies, improves the timing of connections, and streamlines and simplifies the network.

It’s an especially big change in Watsonville, whose confusing tangle of overlapping hourly routes was especially useless for most trips. There, service is restructured to put a majority of the population and jobs near half-hourly service, mostly on lines that run through to the other cities to the west.

In Santa Cruz, the big change is the restoration of 15-minute frequency on the main lines that connect the University of California (“UC Santa Cruz” on the map) with the westside and downtown. This is important not just for the university, but also to support the City’s goals for denser residential developments in the existing neighborhoods south of the campus.

The spine of the network linking Watsonville and Santa Cruz is a braid of four hourly routes currently called 69A, 69W, and 71. In the new network the same resources go into simpler routes 1 and 2, and they’re more precisely scheduled to provide a 15-minute frequency on their westernmost segment where they run together. Halfway between Santa Cruz and Watsonville, these two routes combine again to serve Cabrillo College, the only community college in the county. We have shown the frequency there as every 20 rather than every 15 because if Routes 1 and 2 leave downtown Santa Cruz spaced evening every 15 minutes, they won’t be as evenly spaced at Cabrillo College, since Route 2 will have taken a longer path. Still, this is a significant frequency improvement for the county’s biggest transit destination outside the University.

Santa Cruz Metro is rolling out this change very fast, aiming to have the new service on the street in December. Meanwhile, this is just the first phase of a more ambitious expansion that will be discussed with the public soon in hopes of further frequency expansions in 2024. That next phase would extend high-frequency local-stop service to Watsonville, while also adding an all-day Santa Cruz-Watsonville Express. It will also look at new continuous service from the University to the east side of Santa Cruz. We look forward to a robust public discussion of that next phase.

At our firm, we are ready to help any transit agency work with its financial situation, whatever it is. But it’s especially exciting to see a transit agency that’s able to grow its services to match the values and ambitions of the communities it serves.