On Sunday June 24, 2018 Richmond, Virginia will wake up to a new transit system, including its first Bus Rapid Transit line — the Pulse. The redesigned network for the whole city is the result of a design process that our firm guided, in cooperation with the local office of Michael Baker International, for the City of Richmond and Greater Richmond Transit Company (the transit agency).

The redesign process began in early 2016 with our team leading city staff, stakeholders and the public in a conversation sparked by our Choices Report. We focused on key trade-offs, like ridership versus coverage and the right balance between peak service and all-day service. Importantly, this project was led by the City of Richmond, not the transit agency, so it was closely aligned with the city’s own goals for itself, including its redevelopment.

We then developed three concepts of how to redesign the City’s bus network around the new BRT line and guided a conversation around those concepts and the goals they represented. The Familiar concept represented little change. A Coverage concept focused on covering every part of the city even where ridership would be low. A Ridership concept focused more on high-ridership services, like frequent lines in high-demand corridors. Response from the public and stakeholders leaned toward the Ridership concept, though there was a wide diversity of opinion.

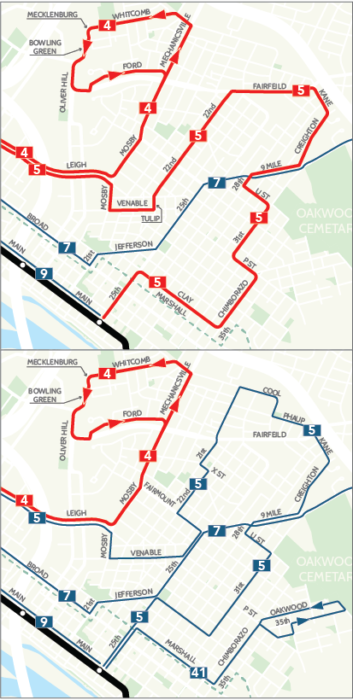

The top map shows the original proposal for the east end of the city. Red = every 15 minutes. Blue = every 30 minutes. Residents told us they preferred shorter walking distances and lower frequency, so we revised the proposal to the map below.

By January 2017 we published a draft recommended network with six new high frequency lines in addition to the BRT, clockface frequencies, more through-routing (instead of terminating) downtown, and a network that maintained nearly all existing coverage of people and jobs.

While response to the draft recommendation was very positive, the East End of the city raised some concerns. We had designed a high frequency line (Route 5 in the map) that required a longer walk for some residents. After more thought and review, the community and the city decided they would prefer to have shorter walks and longer waits. So, we revised the network design to have two lower frequency lines (Routes 5 and 41 in the map) instead of one higher frequency line.

We published the final network plan in March 2017 and since then the City and GRTC have been working hard to prepare for the big day when everything changes overnight, including additional tweaks and updates to the network in light of new information and additional community feedback. But overall, the basic network structure that will be implemented on June 24 is what was in the final plan from March 2017.

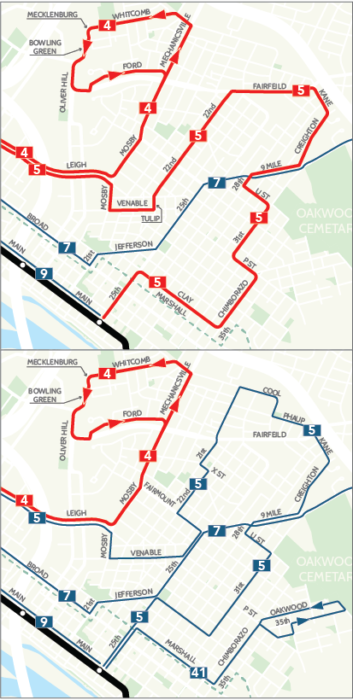

You can see how the new network drastically simplifies things by comparing the existing system

The top map shows the network before the redesign and the lower map shows the network after the redesign.

map to the new map in near west part of the city, which includes the Fan and Museum District neighborhoods. Previously, many routes piled together onto Broad Street to create a lot of service there, but it was not well organized and led to more bunching of buses than useful frequency. The new network is radically simpler, with more direct lines and frequent lines focused on the major east-west corridors in this part of the city. So there are now two major frequent lines in this area, the BRT line on Broad Street and the frequent Route 5 on the Main/Cary couplet.

And there is a new orbital line (Route 20) connecting the north, south and west parts of the city without requiring a transfer downtown. This is really important for Richmond because of the prevalence of jobs in the western part of the region while most lower cost housing is in the north, south, or east. We wanted this line to be every 15 minutes, and we hope it will be soon; for now, budget constraints are holding it to a 30 minute frequency.

Also, GRTC has taken this opportunity to improve the communication in its system map. In the old map colors represented which parts of the city each route served. In the new map, colors represent frequency, which makes it much easier to see where the useful service is. (The new map is by our friends at CHK America, but the red-blue-green color scheme for frequency is one we’ve been using for years.)

Throughout the process we led the network design and guided the stakeholder conversations. We worked closely with our local partners at Michael Baker International who led the public outreach and key local government coordination. And the City provided strong leadership throughout to ensure the process led to a clear and convincing direction when City Council unanimously approved the policy direction for the plan in February 2017.

We’ve had fun working with GRTC, the City and surrounding counties on a ten-year plan for transit improvement. We’ve been leading an intensive effort on the network design in Henrico County, which covers Richmond’s northern suburbs, including concepts for a major expansion of transit into the county. That is all leading toward a new Transit Development Plan for GRTC which will be completed in the next few months. Meanwhile, Henrico County has already taken major steps to implement parts of the plan. Starting in September, there will be evening and weekend service on three routes in Henrico (currently they do not have any service in the evening or on weekends). They will also extend service to the airport and along West Broad Street to Short Pump to serve the one of largest suburban office parks in the region and the largest shopping mall in the region.

When local governments start leading on transit, big things can happen. The fast movement on so many fronts in the last two years is due, in part, to the City of Richmond and Henrico County taking a much stronger role in guiding and planning for transit in coordination with GRTC, instead of leaving all the advocacy to the transit agency.

We’re pleased to have helped shepherd the conversation to this point, but much credit goes to all the GRTC, City, County, State, and regional agency staff (and other supporting consultants) who have worked hard on these issues for years and to the local transit advocates and organizers who have built grass roots support for more transit across the region.

So, get excited, Richmond and Henrico, for your new transit system is coming soon. And for those of you from other places who are interested in experiencing a transit redesign first hand, perhaps you should plan a long weekend trip to Richmond for the June 24 opening. You could even volunteer to help with the changeover!