I’ve been thinking out loud about microtransit for a week now, and have processed lots of great comments. But if you comment, don’t just respond to this post. Go to the detailed posts that really lay out the argument: Is microtransit an actual idea? Does that matter? And most importantly: Is microtransit capable of being a sensible investment that can be justified from widely accepted goals of public transit?

To sum up, here’s what I think we know. As always, I’m open to enlightenment by anyone who reads these posts and wants to engage my argument. I’m not contrarian for its own sake. My job is simply to help transit agencies make clear decisions whose consequences they understand.

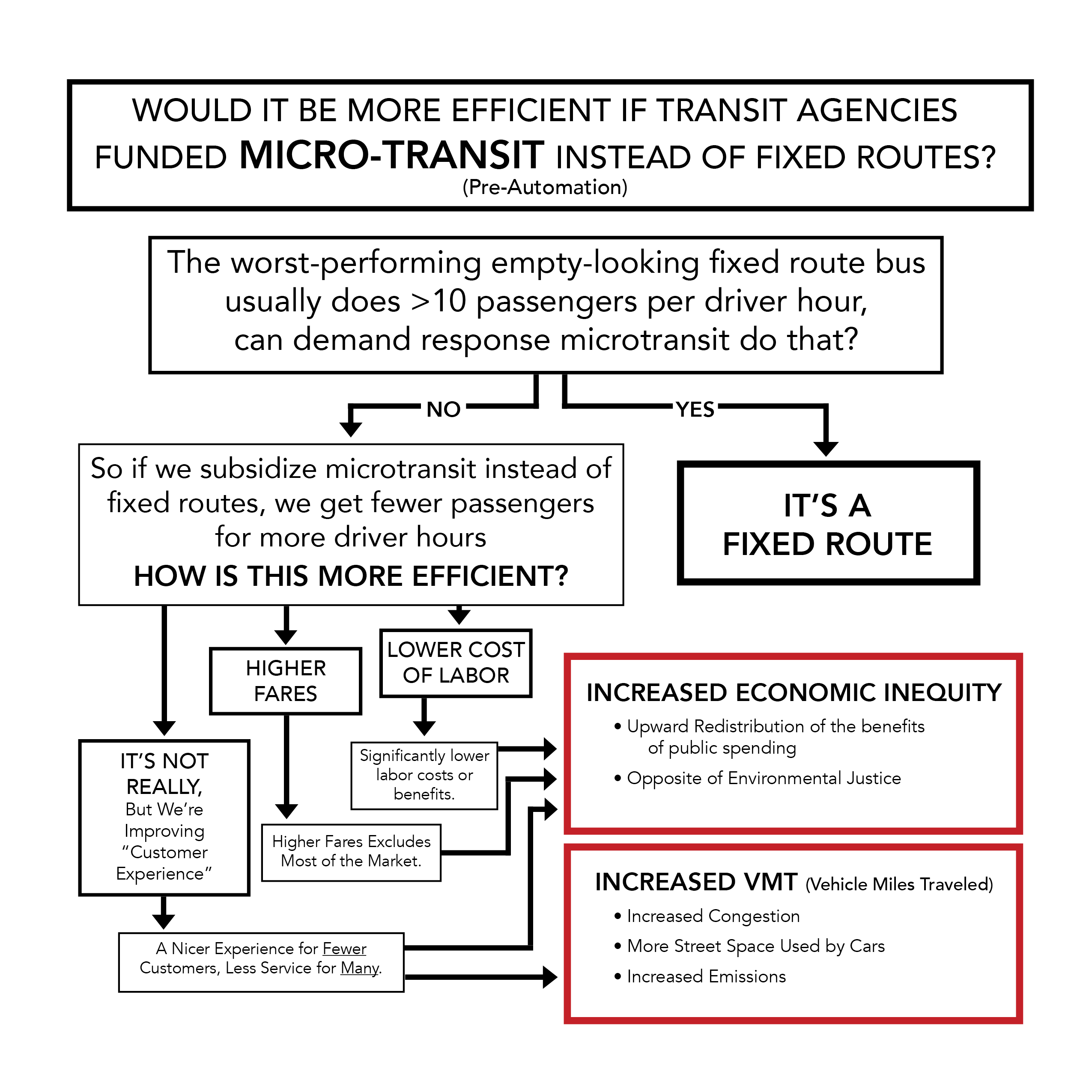

The context for this thinking is pre-automation, so labor cost is a dominant issue. The question is whether transit agencies should subsidize microtransit, which implies that microtransit is in direct competition for funds with other possible transit agency investments. Thus, the question is about the public interest and benefits to the taxpayer.

Microtransit May Be a Slogan, Not an Idea

As I explored here, microtransit seems to consist of:

- flexible “on-demand” routing, an idea that transit agencies have known about, and experimented with, for decades.

- subsidies of privately provided services by a transit agency, which has been happening for decades under a range of contracting arrangements.

- the use of apps for hailing, navigation, and payment.

Only the last of these is new, but there’s reason to doubt that the apps, by themselves, create a radically new business model. (Evidence that they do could include Uber being more profitable than non-cartel taxis were, controlling for labor costs.) In any case, the statement “transit agencies should consider microtransit” can be translated as: “Transit agencies should use apps to improve the efficiency and customer experience of their flex-route services.” Put that way, it’s uncontroversial and hardly justifies all the hype.

Watch the Ratio of Drivers to Passengers

In transit, before automation, operating cost is mostly labor. Even if you race to the bottom on labor costs, as Uber has done, you won’t save more than 50% off of transit’s big bus operating cost. You still need one driver for every vehicle. That’s why passenger transport services, unlike Amazon, don’t become much more efficient as they get bigger.

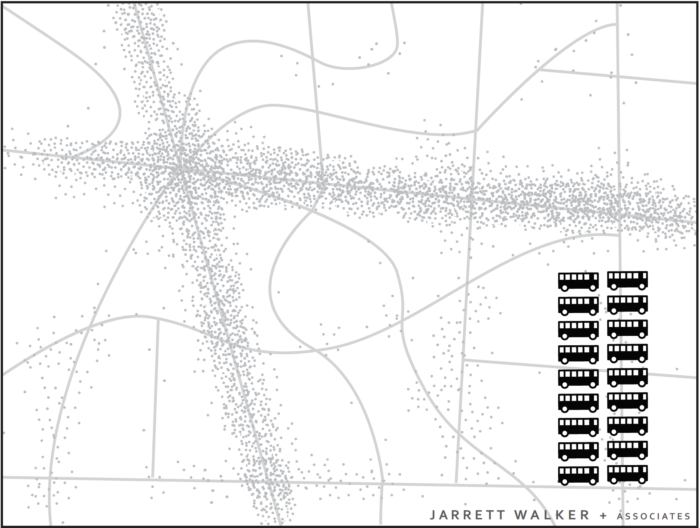

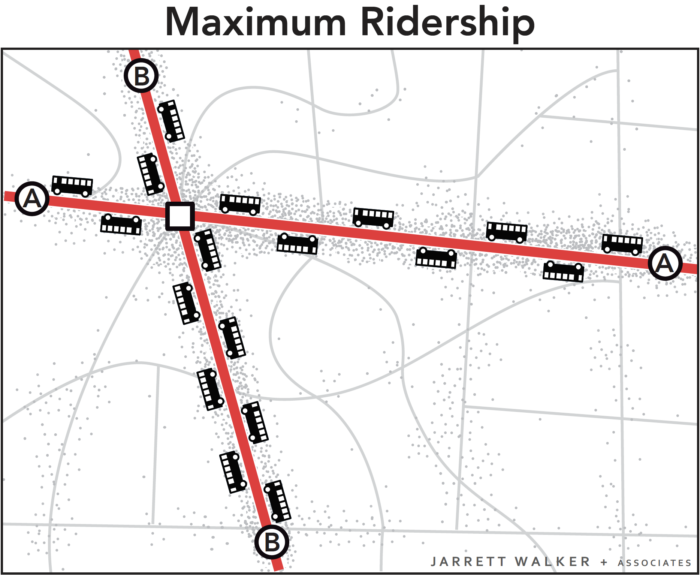

That means efficiency in transit is the ratio of passengers to drivers. Microtransit, by definition, is a low-capacity service, carrying small numbers of people at a time. This is, by definition, a way to serve very few people at very high cost, compared to fixed routes.

And as soon as we talk about transit agencies funding microtransit, we are saying that they should do this instead of adding fixed route services that are proven to attract vastly more riders and serve them vastly more efficiently (see table in this post.).

Do Not Confuse Customer Experience with Financial Viability

A common rookie investing mistake is to buy a company’s stock solely because you love its product. Successful ventures don’t just provide a good product or customer experience. They do it in a way that’s financially viable. In the private sector that’s measured in profit. In the public sector the equivalent idea is some kind of cost/benefit or “bang for buck” ratio. Microtransit’s performance on those measures is generally worse than terrible, just as the performance of flexible-route services has always been. Talking about microtransit’s superior “customer experience” doesn’t change that fact.

For example, a recent Eno Foundation report promoting microtransit cited two pilots that achieved less than 1 (one) passenger trip per vehicle service hour. A decent fixed route bus does 20-100 and most terrible fixed routes do at least 10. The most upbeat data Eno’s report could find was a microtransit pilot in Newark, California that achieves 3 passengers/hour, but this is down from 7 passengers/hour on the fixed route it replaced. The transit agency lost 20% of the old route’s ridership when it made this change. And that is the most hopeful data point that microtransit boosters can cite.

Microtransit’s Poor Performance is a Mathematical Fact, not Question of Technology, Social Science, or Marketing

Transit agencies not only have decades of experience with low-performing flexible route experiments. There’s also a purely geometric argument for why fixed routes perform so much better in almost all cases. It’s about the way the customer’s walk to a fixed route stop allows the bus to operate on a straighter path that’s more likely to be useful to more people. The correlation between fixed route performance and the straightness of the route is very strong. Microtransit is meandering by definition, as it has to roam a large area and pick up people who are not in any kind of linear path. Technology never changes geometry.

Microtransit is Not a Way to Increase Ridership Overall

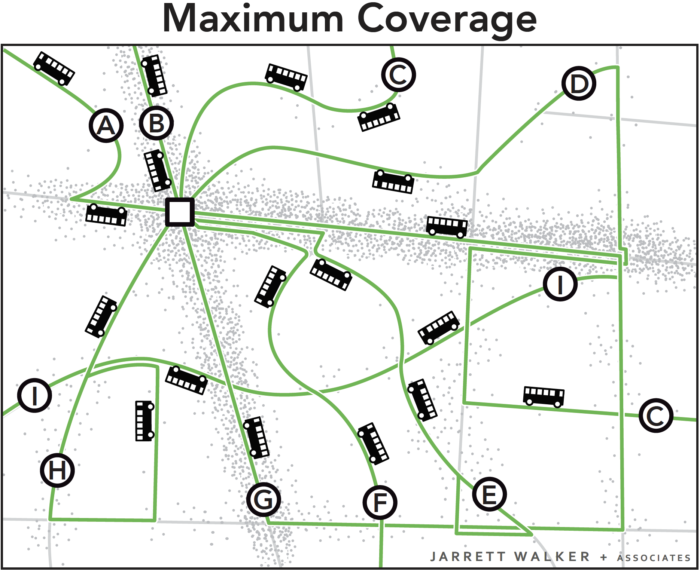

Because of its low productivity, transit agency funding of microtransit arises from a coverage goal, which is the opposite of a ridership goal. Coverage means “predictably low ridership service run for a non-ridership reason,” typically access to places where the built environment makes high-ridership service impossible. The microtransit boosters assume that agencies must run lots of coverage service but this is actually an issue that should be debated; many agencies I’ve worked with have shifted their priorities the other way.

This also means it is incoherent to cite a desire for higher total ridership, or disappointment with declining ridership, as a reason to invest in microtransit. If you want higher ridership, you invest in services that are physically capable of carrying lots of riders and have a proven ability to attract them when run at sufficient quality, like big-bus fixed routes. Microtransit is about taking both funds and political attention away from the services that are actually relevant to ridership at a large scale.

I Cannot Reconcile Microtransit with Economic Equality or Environmental Justice Goals

On average, microtransit seems to trigger an upward redistribution of the benefits of public subsidy. This is a Very Bad Thing for the public sector. It is not hard to make some low-income or social service advocates like a microtransit idea from the customer perspective, and see it as liberating for their clients, but if it isn’t financially viable at a large scale, it won’t matter to the vast majority of disadvantaged people.

If a transit agency invests in a microtransit service hour for 3 people instead of a fixed route service hour for 30 people, solely to give those 3 people a better “customer experience,” we must ask “why are these 3 people so special?” Why shouldn’t they pay the full cost of their superior customer experience, rather than expecting the taxpayer to subsidize it? More on this line of thought here.

Unlike private businesses, U.S. transit agencies operate under intense scrutiny about equity outcomes. Civil rights and environmental justice tests are much more extensive for transit agencies than to the private sector, largely because they are conditions of Federal funding that these agencies rely on. We have not begun to see the blowback against microtransit from environmental justice and civil rights perspectives, but if fixed routes are neglected to fund microtransit investments, the math is potentially there to justify it.

The Popularity of Microtransit Has Explanations Unrelated to its Value

The microtransit movement, like so many fads that have blown over transit agencies during my 25-year career, appears to be an example of elite projection, the tendency of fortunate people to assume that whatever they personally like will be good for society as a whole. An urban elite has seen their lives transformed by ride-hailing services, and understandably wants to believe that this transformation can be brought to transit too. This helps to explain why so much talk of microtransit is so dreamy, so obviously stated in the tone of a sales pitch rather than an analysis. To think clearly in this context, you need to lean into the wind, being skeptical but not cynical about ideas that obviously serve someone’s commercial interest.

The Talk about Microtransit May Be Doing Harm

Fixed routes are spectacularly cost-effective investments compared to almost any flex-route option. They even do better in cases (as in Newark, California above) where the geography is very unfavorable to fixed route success. The reasons for this are geometric, as described above, so technology won’t change them.

Recent declines in bus ridership are triggering all kinds of triumphalist claims from people who want to sweep fixed routes away, or at least shift resources away from them as the microtransit movement proposes. Much of this chatter is intended to push transit experts out of the discussion by implying that their expertise is obsolete. The rigidity of fixed routes, the chatter suggests, arises from rigid minds.

But the neglect of fixed routes, encouraged at the highest levels, is the real source of transit’s declining relevance. My firm works in cities all over the US, and most of them have appallingly low levels of fixed route service compared to potential demand. In most American cities, the quantity of service is growing far slower than population, which means that on average, the availability and usefulness of transit is getting worse. Most cities, in short, are forcing low-income people to buy cars by making that the only way to have a life, even in places where fixed route service could succeed.

In this reality, should transit agencies really focus on ways to move tiny numbers of people more expensively, to deliver them a special “customer experience”, as the microtransit idea proposes? Clearly that’s not the path to ridership.

Meanwhile, cities that are forcefully recommitting to fixed routes are bucking the trend of falling ridership, and these show a clear path. Ridership is up in Seattle, despite all the countervailing trends, because of an unusually high commitment to quality service and to protecting fixed routes from congestion — a commitment shared by the transit agency and the City of Seattle. Houston continues to do far better than its Texas peers, partly due to the 2015 network redesign that expanded the bus network’s usefulness.

We know how to increase ridership. It’s by offering useful, civilized, and cost-effective mobility to large numbers of people, not obsessing about the customer experience of a few. And while ridership is not the only goal of transit, it’s hard to get to microtransit from any of transit’s other common goals either.

If You’re Going to Comment …

I would love to see comments engaging my argument. I’m not especially interested in comments that ignore my argument, or change the subject, or give me dreamy visions of a future where laws of math have been repealed, or lecture me about how I represent tired old thinking. If you’re going to challenge me on a point where I’ve linked to another article, follow that link and read that article, because the meat of that argument may be there.

Thanks for your help making me smarter about this. I advise a lot of transit agencies, and I want to best for them and the cities they serve.