That’s the real title of my piece in Citylab today. Read it here.

Portland Plans Faster, More Reliable Buses

The Portland Bureau of Transportation has released the long-awaited Enhanced Transit Corridors plan, a set of policies and strategies to increase the speed and reliability of Portland’s major bus lines. As in many cities, Portland’s bus lines have been slowing down about 1% a year, which is slowly eating away at people’s access to all kinds of opportunity.

The Portland Bureau of Transportation has released the long-awaited Enhanced Transit Corridors plan, a set of policies and strategies to increase the speed and reliability of Portland’s major bus lines. As in many cities, Portland’s bus lines have been slowing down about 1% a year, which is slowly eating away at people’s access to all kinds of opportunity.

The plan also points the way for the City of Portland to be a more active leader in transit policy, much as the City of Seattle has done so effectively.

The Portland Bureau of Transportation invited me to draft the Executive Summary, which offers some examples of ways to make this topic urgent for more people. I’m happy with how it came out, and people fighting similar battles in other cities may find it useful.

Here’s the Executive Summary. Here’s the rest of the report.

Portland residents: Have your say at or before the City Council hearing on June 20 at 2 pm, in the Council Chambers. You can also submit comments before June 20 by writing to cctestimony at

The rise of “Super Commuters”

The Apartment List Rentonomics blog, which writes on real-estate statistics and economics, recently posted a census analysis on the “Rise of Supercommuters”. It describes a recent increase in the percentage of people with commutes 90 minutes or longer each way. This thoughtful analysis is well worth a read. It finds that:

- Nationwide, one in 36 commuters are super commuters, traveling 90+ minutes to work each day, spending hours on public transportation or battling traffic.

- Super commuting is becoming increasingly common: the share of super commuters increased 15.9 percent from 2.4 percent in 2005 to 2.8 percent in 2016.

- The share of super commuters is highest in expensive metros with strong economies — New York, San Francisco, Washington, D.C., Atlanta and Los Angeles, and in their surrounding areas.

- Super commuters are more likely to rely on public transportation than those with shorter commutes. An estimated 91.4 percent of non-super commuters drive to work, compared to just 69.7 percent of super commuters.

- In most U.S. metros, low-income commuters are more reliant on public transportation than high-income commuters, creating a nexus between super-commuting and poverty. When transit usage falls sharply with income it suggests that transit is used out of financial necessity rather than as a lifestyle choice.

But the term “Super Commuter” sounds too heroic. “Super commutes” aren’t something to celebrate. People should be free to arrange their lives this way, but shouldn’t be forced to by the housing market.

For the commuter, spending three hours of unpaid time a day commuting is only a response to a lack of reasonable alternatives. For taxpayers, it represents a high cost- both in providing infrastructure, and in increased traffic congestion. The US Census itself calls commutes over 90 minutes “Extreme commutes”. That to me, better describes these long commutes- they are something that a few people may have to do because of their job or family situation, but something that shouldn’t be made the new normal. “Extreme” also captures the right connotation. As in “extreme sports,” it suggests something that most people would rather watch than do, and that many don’t even want to hear about.

We can also draw parallels between increases in in the prevalence of these extreme commutes and the decrease in overall transit ridership over the past few years. They are both symptoms of the suburbanization of poverty, and to some extent, the middle class. These suburbs are not geometrically conducive to high-ridership transit, and as a result the transit options are poor, so many people who move there, resort to driving. But driving such long distances every day can cost thousands of dollars over the course of a year, so some people would still rather endure the low frequencies and limited spans of suburban transit service to access the city.

The article goes on to conclude that:

Reversing the growth in super commuting requires investment in both increasing housing supply and improving transportation.

Both increasing housing supply and improving transportation have the potential to reduce commute distances, but the location of this new housing and improved transportation are crucial. Transit always achieves higher ridership per hour of service in dense, mixed-use urban centers, than in unwalkable outlying suburbs, so if we want to reduce the percentage of transit commutes that take more than 90 minutes each way, we will have to substantially increase densities in places where fast, frequent, and useful transit is most feasible. That means a mixture of housing and jobs, and building up, not out.

Santa Cruz: Video of My Evening Presentation

In May 2017 I made a quick trip to Santa Cruz, California to do presentations both to the public and to the Regional Transportation Commission. Some of my presentation is my usual shtick, but I also talked a lot about chokepoints in the Bay Area, and was also asked to comment on a local proposal (proponents, opponents) to remove the rails from a rail corridor in order to create a wider and more attractive active modes path (though a functional path alongside the rail is possible in any case.)

It’s here. There’s quite a Q&A as well.

Is Anyone Owed a Transit Line?

San Francisco’s regional rapid transit agency, BART, just voted not to build a long-planned extension to the eastern suburb of Livermore.

To create the consensus to start the BART system, over 50 years ago, unfunded promises were made of future extensions into outer suburbs. The need to fulfill these promises is one of the top arguments for these extensions.

But are these promises wise, or for that matter, should they be believed?

When you promise some Town X a transit line, that’s logically equivalent to saying: “You in Town X don’t have to do anything to make this line happen, or succeed.” In other words, it doesn’t matter whether Town X …

- … allows the transit line to go a place where there will be destinations in walking distance, and where it’s safe and easy to walk.

- … plans major intensification around the transit line, so that there will be lots of demand there.

- … allows the line to be built in a way that’s reasonably cost-effective for the transit agency.

This problem arises with all kinds of transit, from rapid transit lines to local bus services. Leaders from Town X talk about transit as though it’s their entitlement as taxpayers, rather than something that they have to help succeed. Logically, this leads to creating more transit lines where the necessary conditions for success are absent. That leads, in turn, to accusations that the transit system is failing, when in fact it’s running intentionally low ridership services for non-ridership reasons.

A similar problem arises when the transit agency allows itself to be the sole advocate for a transit expansion to Town X. This gives Town X the same message: The transit agency will do all the work; we don’t really have to help. That’s why I am always advising that advocacy for expansion should not come from the transit agency.

So be careful what you promise, and be careful how seriously you take unfunded promises, especially ones made long ago. In ridership terms, transit succeeds only in partnership with local government. For that partnership to work, it must be clear that if the local government doesn’t do what’s really needed, the transit may not happen.

Richmond, Virginia: our Redesigned Network starts June 24!

On Sunday June 24, 2018 Richmond, Virginia will wake up to a new transit system, including its first Bus Rapid Transit line — the Pulse. The redesigned network for the whole city is the result of a design process that our firm guided, in cooperation with the local office of Michael Baker International, for the City of Richmond and Greater Richmond Transit Company (the transit agency).

The redesign process began in early 2016 with our team leading city staff, stakeholders and the public in a conversation sparked by our Choices Report. We focused on key trade-offs, like ridership versus coverage and the right balance between peak service and all-day service. Importantly, this project was led by the City of Richmond, not the transit agency, so it was closely aligned with the city’s own goals for itself, including its redevelopment.

We then developed three concepts of how to redesign the City’s bus network around the new BRT line and guided a conversation around those concepts and the goals they represented. The Familiar concept represented little change. A Coverage concept focused on covering every part of the city even where ridership would be low. A Ridership concept focused more on high-ridership services, like frequent lines in high-demand corridors. Response from the public and stakeholders leaned toward the Ridership concept, though there was a wide diversity of opinion.

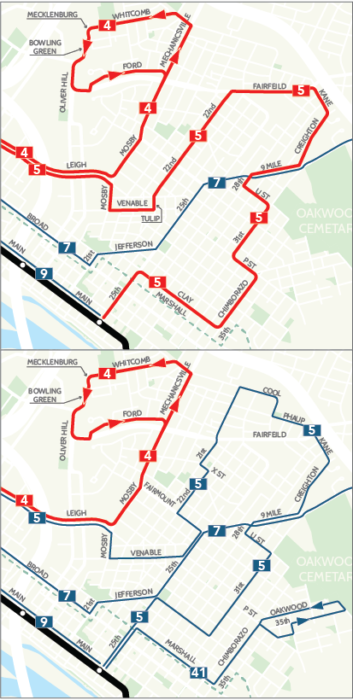

The top map shows the original proposal for the east end of the city. Red = every 15 minutes. Blue = every 30 minutes. Residents told us they preferred shorter walking distances and lower frequency, so we revised the proposal to the map below.

By January 2017 we published a draft recommended network with six new high frequency lines in addition to the BRT, clockface frequencies, more through-routing (instead of terminating) downtown, and a network that maintained nearly all existing coverage of people and jobs.

While response to the draft recommendation was very positive, the East End of the city raised some concerns. We had designed a high frequency line (Route 5 in the map) that required a longer walk for some residents. After more thought and review, the community and the city decided they would prefer to have shorter walks and longer waits. So, we revised the network design to have two lower frequency lines (Routes 5 and 41 in the map) instead of one higher frequency line.

We published the final network plan in March 2017 and since then the City and GRTC have been working hard to prepare for the big day when everything changes overnight, including additional tweaks and updates to the network in light of new information and additional community feedback. But overall, the basic network structure that will be implemented on June 24 is what was in the final plan from March 2017.

You can see how the new network drastically simplifies things by comparing the existing system

The top map shows the network before the redesign and the lower map shows the network after the redesign.

map to the new map in near west part of the city, which includes the Fan and Museum District neighborhoods. Previously, many routes piled together onto Broad Street to create a lot of service there, but it was not well organized and led to more bunching of buses than useful frequency. The new network is radically simpler, with more direct lines and frequent lines focused on the major east-west corridors in this part of the city. So there are now two major frequent lines in this area, the BRT line on Broad Street and the frequent Route 5 on the Main/Cary couplet.

And there is a new orbital line (Route 20) connecting the north, south and west parts of the city without requiring a transfer downtown. This is really important for Richmond because of the prevalence of jobs in the western part of the region while most lower cost housing is in the north, south, or east. We wanted this line to be every 15 minutes, and we hope it will be soon; for now, budget constraints are holding it to a 30 minute frequency.

Also, GRTC has taken this opportunity to improve the communication in its system map. In the old map colors represented which parts of the city each route served. In the new map, colors represent frequency, which makes it much easier to see where the useful service is. (The new map is by our friends at CHK America, but the red-blue-green color scheme for frequency is one we’ve been using for years.)

Throughout the process we led the network design and guided the stakeholder conversations. We worked closely with our local partners at Michael Baker International who led the public outreach and key local government coordination. And the City provided strong leadership throughout to ensure the process led to a clear and convincing direction when City Council unanimously approved the policy direction for the plan in February 2017.

We’ve had fun working with GRTC, the City and surrounding counties on a ten-year plan for transit improvement. We’ve been leading an intensive effort on the network design in Henrico County, which covers Richmond’s northern suburbs, including concepts for a major expansion of transit into the county. That is all leading toward a new Transit Development Plan for GRTC which will be completed in the next few months. Meanwhile, Henrico County has already taken major steps to implement parts of the plan. Starting in September, there will be evening and weekend service on three routes in Henrico (currently they do not have any service in the evening or on weekends). They will also extend service to the airport and along West Broad Street to Short Pump to serve the one of largest suburban office parks in the region and the largest shopping mall in the region.

When local governments start leading on transit, big things can happen. The fast movement on so many fronts in the last two years is due, in part, to the City of Richmond and Henrico County taking a much stronger role in guiding and planning for transit in coordination with GRTC, instead of leaving all the advocacy to the transit agency.

We’re pleased to have helped shepherd the conversation to this point, but much credit goes to all the GRTC, City, County, State, and regional agency staff (and other supporting consultants) who have worked hard on these issues for years and to the local transit advocates and organizers who have built grass roots support for more transit across the region.

So, get excited, Richmond and Henrico, for your new transit system is coming soon. And for those of you from other places who are interested in experiencing a transit redesign first hand, perhaps you should plan a long weekend trip to Richmond for the June 24 opening. You could even volunteer to help with the changeover!

GRTC is recruiting volunteers to assist with the removal of the temporary covers on bus stops on June 22nd & June 23rd. The removal will reveal all the route numbers, & new stops that will be part of the new bus network starting June 24th. Sign up now: https://t.co/RMyLFqXPWX pic.twitter.com/swyw0WTXJR

— GRTC (@GRTCTransit) April 30, 2018

What is “Development Oriented Transit”?

Chuck Marohn of the excellent organization Strong Towns doesn’t like transit-oriented development (TOD), and instead recommends “development-oriented transit” (DOT?) in a 2014 piece quoted by Rachel Quednau today. Debates about TOD and DOT have been around for a while, but are they really about anything?

Here’s Marohn:

Transit-oriented development is the transit-advocate’s response to highway strip development in the same way that the early planned New Urbanist developments like Seaside were a response to greenfield suburban development. I’m sympathetic, but this isn’t the answer.

Instead of transit-oriented development, we should have development-oriented transit: Identify places where things are happening now and then connect them with the lowest level of viable transit possible. Make sure those places allow the next increment of development by right (without extensive permitting). This will ensure that the transit is viable and that it supports that next level of growth and expansion.

When that next level of growth and expansion happens, everything moves up a notch. Upgrade the transit to the next level — from jitney to shuttle bus, from shuttle bus to city bus, from city bus to streetcar, from streetcar to light rail, from light rail to subway — and repeat.

This is a beautiful idea that will make no sense to an actual transit planner. It would be nice if you could start out with a low commitment to transit and then grow it as demand requires. But this approach routinely fails when communities do grow to the scale that requires high capacity transit, only to find that there is nowhere to develop effective transit because it wasn’t considered at an early stage.

This is the argument for ensuring public ownership of key rights-of-way, like abandoned railway corridors and utility corridors, and retaining the option for putting transit there in the future. That much is usually not controversial.

But if we accept that, then it implies a greater challenge. New towns need to be along a possible future right of way, so that future transit will serve them.

One of the most common mistakes of New Urbanist development is to build “transit-oriented” villages in places where efficient transit could never reach them. Usually, this is because the village is in a cul-de-sac location position with respect to the larger network, so that transit can’t run through it on the way to anywhere else. I explain this problem more fully here. In my book Human Transit I call out one of the earliest examples, Peter Calthorpe’s Laguna West, but I still encounter them constantly across the US. (Here’s one in Davis, California, for example.)

So we transit planners are entitled to point out where development patterns make transit easier or harder to provide. If the developers want to claim transit as a possible outcome, they must deliver development forms that are adaptable to transit in the future. As Calthorpe and others have pointed out, the worst kind of sprawl is high-density sprawl, where travel demand is intense but the layout makes it impossible to serve with anything but cars. Geometrically, this can only lead to high congestion, high vehicle miles traveled, and a range of other awful outcomes.

So what is “development-oriented transit”? To be frank, I’m sure I’m not the only transit planner who finds the term insulting. What exactly do you think we do all day? Transit planning is a response to transit markets, which arise from the built form, i.e. “development”. If development determines where people are and where they need to go, then all transit is development-oriented, and it always has been.

There is plenty to dislike about certain transit-oriented developments. We must be suspicious of aesthetic objections that could be resolved only at high cost, as this amounts to dismissing the imperative of affordability, but even within that limit there are many ways to make development better or worse.

But in the end, transit-oriented development isn’t some architect’s theory, or even some set of prototypes. It boils down to the idea that transportation infrastructure drives urban form as much as urban form drives infrastructure. Virtually all authentic towns are located and configured in response to some kind of transportation: a port, a rail junction, a road junction, etc. In cities, almost all of the inner city fabric that people love is transit-oriented development, in that it grew around early transit lines.

Transit-oriented development is not the opposite of “development-oriented transit.” All transport is development-oriented, and all development is oriented toward some transport mode. If you want that mode to be public transit, then you need to plan development — not just its layout but also its location – with transit in mind, just as all urban planning did before 1945. That’s all that the term “transit-oriented development” says, and all that it should mean.

New York: Bus Network Redesign on the Horizon!

by Christopher Yuen

MTA New York City Transit has just unveiled a plan today to completely revamp its bus network. Some elements of the plan that will be especially impactful (from their press release) include:

A completely redesigned bus route network. NYC Transit is performing a top-to-bottom, holistic review and redesign of the entire city’s bus route network – the first in decades – based on public input, demographic changes and travel demand analysis. Route changes will provide better connectivity and more direct service in every neighborhood, with updated stop spacing and the expansion of off-peak service on strategic routes.

Collaboration with NYCDOT, NYPD, & local communities. NYC Transit will collaborate with NYCDOT [the city’s Department of Transportation] to expand the implementation of bus lanes, exclusive busways, queue jumps, bus stop arrival time displays and bus priority technology on traffic signals and buses known as “traffic signal priority.” Many of these changes will also require robust community outreach. NYC Transit will also advocate for strengthened [police] enforcement of bus lanes, dedicated transit-priority traffic teams, and legislative approval to expand bus-mounted cameras beyond 16 existing routes to help enforce bus lane rules in more locations. (Most of the big wins in urban transit require transit agencies and city governments to work together.)

Speeding up boarding by using all doors. NYC Transit is pursuing new approaches to speed up bus boarding, particularly using upcoming electronic tap-to-pay readers to facilitate all-door boarding. While purchasing fare media with cash will always be an option with the new fare payment system being developed by the MTA, NYC Transit will also explore cashless options to speed up boarding time in select circumstances.

Transit routes are often tweaked in response to infrastructure changes, local desires, and complaints. Some of these changes serve specialized markets and may work well for some people’s specific trips, but over time, they erode the ability for a system to work well for the everyone else. It takes a clean-slate redesign approach to create a network of simple, frequent and reliable lines. The result, as has been the case in Houston, Coloubus, and Anchorage, is usually less routes in total, but more routes at higher frequencies all day, 7 days a week.

It’s also promising to see the New York MTA include measures to improve the speed and reliability of buses. Since the speed of urban transit is not determined by how fast vehicles go, but by how often they have to stop, increased stop spacing, all-door boarding and properly enforced bus-only lanes will help keep people moving, especially during rush hour when traffic congestion and crowding has its worst impacts. It’s also important to note that for transit, time is money, so faster service means more service for the same operating budget.

New York’s plan is ambitious, and potentially very impactful, so this will be an interesting story to follow over the coming years.

Why Does Ridership Rise or Fall? Lessons from Canada

by Christopher Yuen

With only a handful of exceptions, transit ridership has stagnated or been falling throughout the US in 2017. The causes of this slump have been unclear but some theories suggest low fuel prices, a growing economy fueling increased car ownership, and the increasing prevalence of ride-hailing services are the cause.

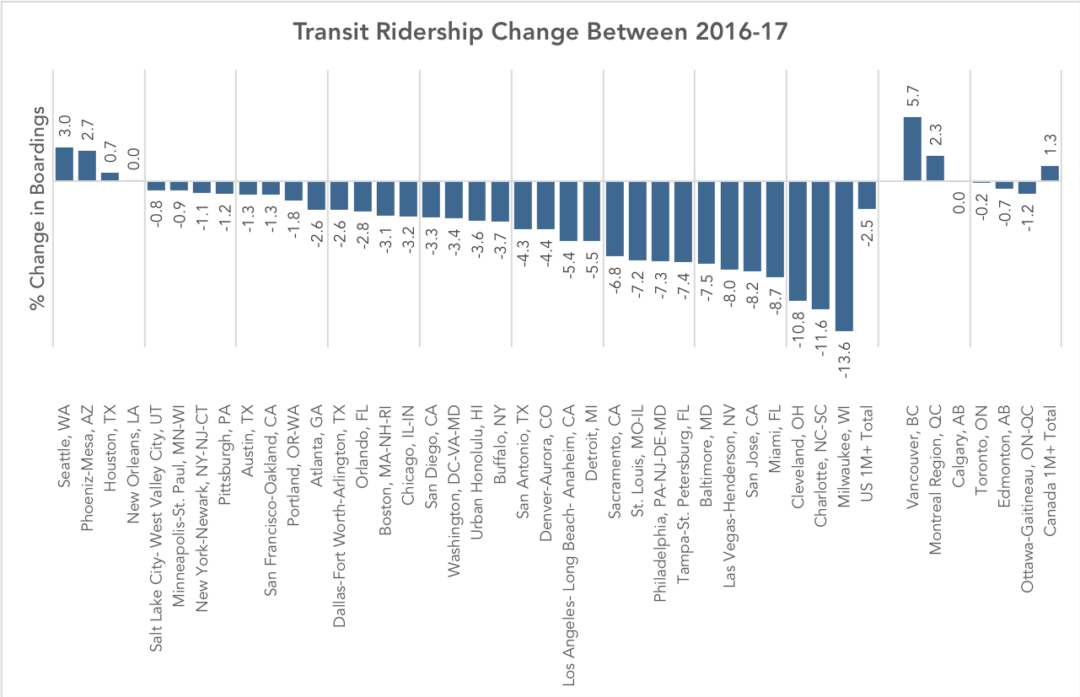

A few North American agencies have bucked the trend, including Seattle, Phoenix, Houston, and Montreal. By far the biggest growth was at Vancouver, BC’s Translink, which saw a ridership growth of 5.7 percent in 2017.

But notice the big picture: In a year when urban transit ridership fell overall in the US, it rose in Canada.

Transit ridership urban areas with populations of over 1M are included in this chart. Ridership of major agencies that serve the same region are added together. (Source: National Transit Database; APTA 2017 Q4 Ridership Report)

There are three interesting stories to note here.

1. If You Run More Service, You Get More Riders

Canadian ridership among metro areas with populations beyond one million is up about 1.3% while regions of the same size in the US saw an overall ridership decrease of about 2.5% in 2017 despite the broad similarity of the countries and their urban forms. Why? Canadian cities just have more service per capita than the most comparable US cities. This results in transit networks that remain more broadly useful in the face of competition from other modes. Note, too, that Canadian transit isn’t cuter, sexier, or more “demand responsive” than transit in the US. There is simply more of it, so more people ride, so transit is more deeply imbedded in the culture and politics.

2. Vancouver Shows the Effect of Network Growth, Higher Gas Prices, Great Land Use Policy, and No Uber/Lyft

Vancouver’s transit ridership has historically been higher than many comparable regions as a result of decades of transit-friendly land-use and transportation policies, including an early regional goal to foster density only around the frequent network. (The Winter Olympics also had a remarkable impact: ridership exploded in 2010, the year of the Olympic games, but then didn’t fall back after the games were over; apparently, many people’s temporary lifestyle changes became permanent.) By North American standards, Vancouver is remarkable in the degree to which development is massed around transit stations.

But Translink attributes its 2017 ridership growth to continued increases in service, high fuel prices, and economic growth. The 11km (7mi) Millennium-line Evergreen Extension just opened prior to 2017, directly adding over 24,000 boardings a day. Fuel prices in Vancouver have also reached an all-time high, at $1.5 CAD / litre (4.4 USD/ gal), an anomaly in North America, although still lower than in Asia and Europe. Economic growth has also been consistent, with the region adding 75000 jobs in years 2016 and 17. Notably, ride-hailing services like Uber and Lyft are not available in Vancouver due to provincial legislation.

3. There is Conflicting Evidence on the Impacts of Economic Growth on Ridership

Many commentators suggest economic growth to be a factor of the 2017 trends in transit ridership but there seems to be two conflicting theories, with economic growth cited as both a cause ridership growth and a cause of ridership decline. The positive link is obvious- economic growth leads to more overall travel, some of which will be made by transit. Contrastingly, the negative link is based on the theory that increasing incomes allow for more people to afford cars. Both theories seem plausible, but for both to be true, the relative strength of each must differ between cities.

Most likely, economic growth in transit-oriented cities is good for ridership, and growth in car-oriented cities, which encourages greater car dependence and car-oriented development, is bad. This would explain the roaring success of Seattle, Vancouver, and Montreal, though it doesn’t explain why Houston and Phoenix are doing so well.

As North American cities work to reverse last year’s losses in ridership, they may best learn from Canada, and a select few American cities, to leverage economic growth for ridership growth.

Postscript by JW

For Americans, Canada is the world’s least foreign country. There are plenty of differences, but much of Canada looks a lot like much of the US, in terms of economic types, city sizes and ages, development patterns, and so on.

So why is Canada so far ahead on transit? All Americans should be asking this. Ask: Which Canadian city is most like my city, and why are its outcomes so different? We’ll have more on this soon.

Webinar: “To Predict with Confidence, Plan for Freedom”

On April 26, I’ll be doing a webinar on my recent Journal of Public Transportation paper, “To Predict with Confidence, Plan for Freedom.” There’s some pretty transgressive stuff in this paper. I hope you’ll join us; details on the webinar are here.

However, attending the webinar is not a substitute for reading the article. It’s nine pages of friendly, non-technical prose. If you read it, you’ll ask better questions in the webinar, which will help other people be smarter, including me.

In fact, I resisted doing the webinar a little bit, because like most philosophical arguments, mine isn’t improved by translation into PowerPoint, or by presentation as any kind of show. On the contrary, you need to be able to sit with it, go back and forth, take it at your own speed, form your own thoughts. This is what reading is for.

Hope to see you, armed with your knowledge of the paper and your questions about it, at the webinar!