Washington DC mayor Muriel Bowser has announced that the DC Streetcar, a single line of mixed-traffic streetcar along a portion of H Street, will be replaced by a “next generation streetcar.” The Washington Post headline cuts through the spin:

If I could have edited that headline, I might just have said “DC Streetcar to be Replaced by Useful Transit”.

What was wrong with the DC Streetcar? Apart from all the problems of putting transit in mixed traffic while denying it the ability to move around obstacles, the problem was this:

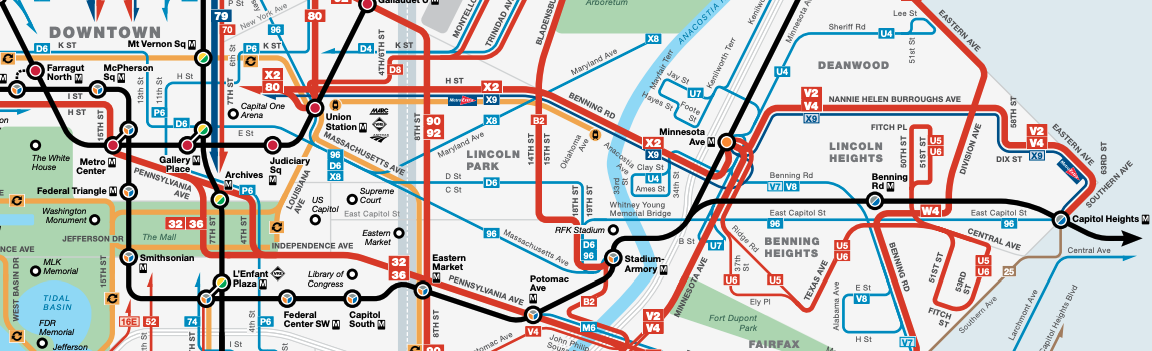

That orange line in the middle of the image, extending from (near) Union Station along H Street to just short of the Anacostia River, is the DC Streetcar. Note that a frequent bus line X2 runs right on top of it but extends further east and west. That’s because the X2, as a bus, is able to operate a complete corridor linking to logical endpoints, and functioning as part of a high-frequency grid. High-frequency grids, which maximize access to opportunity in a dense city, are made of lines that keep going all the way across the grid, so that they intersect as many other lines as possible. One thing an effective grid bus line would never do is end just short of a major connection point, as the streetcar does by not crossing the Anacostia River to at least reach Minnesota Avenue station.

This is one of the key things wrong with most of the mixed-traffic streetcars developed in the US in the 2000-2015 period, and especially those heavily promoted by the Obama Administration. The excitement generated by the development industry, combined with the eagerness to get something started at low cost, led to starter lines that were very short, so they were unable to function well inside of larger grids. The duplication of the X2 and the streetcar is just wasted precious driver time, but the X2 can’t get out of the way of the streetcar because it’s doing important work in a longer corridor, while the streetcar just duplicates part of it. Because the resulting streetcar service was so useless, it never saw the surge of ridership that would form the basis for political support to expand the network.

Across the country now, we’re going to see a divergence in the fates of these little modern streetcars. At this stage, I’m aware of two modern streetcars that I’m really confident will endure: the westside line in Portland and the line in Kansas City, both of which are being extended. Portland’s is, and Kansas City’s will be, long enough to usefully serve a complete corridor rather than just a fragment of it. There are a few other niche streetcars that have strong enough markets. Tucson’s, for example, doesn’t extend across the city’s vast grid but it does link downtown and the University through several walkable neighborhoods, so it makes some sense.

Over time, too, the streetcars that endure are going to be those that gradually transform themselves into something more like light rail, by reducing car traffic’s ability to disrupt the service and widening the spacing of stops. Portland, where the modern streetcar movement was hatched, spent years sending urbanists out across the country saying that “rail is special because it’s permanent.” But fortunately the Portland Streetcar stations weren’t permanent! They were way too close together, and wisely, some have now been removed in the campaign to get the service a bit above its original average speed of 6 miles per hour.

I must admit that when I saw this story, my first reaction on social media was less than magnanimous:

If you weren’t there, trust me. At the major urbanist conferences between 2000 and 2010, few people were saying the obvious things I was saying, namely:

- The permanence of a service lies not in rails in the street, but in the permanent justification of the operating subsidy. That depends (in part) on ridership, which depends on the land use that actually develops around the line, not just what the boosters fantasize. Many US cities facing budget crises now have streetcar operations on their books that compete directly with other city priorities, and if the streetcar wasn’t designed to succeed, they may not win those battles every year.

- Streetcar lines that are too short, and serve only parts of corridors that really need to be served continuously, are net barriers to transit access, reducing access to opportunity. They either require us to take apart corridors that serve more people if they’re continuous, or they require a bus and streetcar to duplicate each other, wasting the precious staff time that is the primary limit on the total quantity of transit service.

This, one of my first really viral pieces from 2009, captures how I was talking back then. I also got into a notorious 2010 fight with Vancouver urbanist Patrick Condon about his vision of covering Vancouver with slow streetcars instead of fast, driverless, high frequency rapid transit. But as always, having been right in the end is never much consolation. Mostly I’m sad that so much well-intentioned energy went into so many projects that weren’t scaled to succeed, and that weren’t sufficiently focused on being useful.

Let’s plan public transit with the goal of being maximally useful to human beings, expanding their access to opportunity. That means designing the right lines first and then picking the technology, not falling in love with a technology and then designing a line around its limitations.

Having been a DC resident at the time, my view is that the streetcar served its purpose admirably–to focus and promote development of the “H Street corridor”. This effort was wildly successful (though assigning causality to the streetcar is perhaps dubious). With that done, the justification for the investment to continue service is no longer valid.

I hope more cities will start with what people actually need rather than just what looks good on a brochure. Looking forward to seeing how DC rethinks this – hopefully in a more people-focused way.

I always find it strange that permanence is considered a virtue with transit. This assumes that we are infallible when it comes to planning which is absurd. Even if we are, cities change (and they should change). The fact that metros have a certain amount of permanence is a vice, not a virtue. Across the globe there are agencies wishing they had done things differently. But changing things after it is built is very expensive. In contrast moving a bus line is quite cheap. Thus the bar is raised quite high for streetcars (although not as high as it is for metros). You have to get it right the first time and quite often they don’t.

Not only does demand change, but traffic changes as well. A streetcar may not have needed the additional right-of-way when the project started but needs it now. Even if the route remains ideal the tracks make improving the right-of-way more difficult. Maybe the best way to avoid traffic is run the streetcar in the middle of the street but that gets expensive if the tracks are to the side. Other modes need to be considered as well.

There are examples of this problem in Seattle*. This is Jackson, one of the busiest streets in Seattle: https://maps.app.goo.gl/4zaYuEqTpHMdkSQo9. Several buses converge here as well as the more popular of the two streetcars. The buses routinely get delayed here. Speeding up the buses (and the streetcar) would help tens of thousands of riders (directly or indirectly). As you can see, the streetcar runs in the middle. But it doesn’t have unique right-of-way. It is stuck in traffic just like the buses that run curbside. There is no cheap solution. You could expand the fleet of buses with doors on both sides and run them for every route. Some of these are trolleys and some of them aren’t which would push up the cost. Any other change would require moving the tracks — which is also expensive. For example you could have the buses run in the center but “weave” like in this picture: https://i0.wp.com/seattletransitblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/segment1_busway-1.png. That allows buses with curbside doors to serve center platforms**. But it would mean moving a lot of tracks. Likewise just adding curbside bus-only lanes would require moving the streetcar tracks (or having the streetcar stuck in even worse traffic). The point being that the “permanence” of the streetcars is not a good thing.

This is not unique to this street or even this streetcar line. The other line has a complicated mess as it gets close to South Lake Union. Both transit and biking suffer as a result. There is a simple solution but it first starts with getting rid of the streetcar: https://seattletransitblog.com/2024/10/04/replacing-the-south-lake-union-streetcar/

*For a relatively small city Seattle seems to have a bit of everything when it comes to transit. One of the few things it doesn’t have is an automated metro but its closest neighbor (Vancouver BC) has that.

**I call it “weave” but there may be a better industry term for this.

The flexibility of bus systems is definitely an advantage to the operator, but for the user it means there’s a constant concern that the bus line they use may be, if not outright withdrawn, be rerouted in a way that makes it less convenient for them. This makes many people afraid of planning their lives around buses, because they could be taken out from beneath them. Such rerouting can’t happen with streetcars – they be withdrawn, of course, but that’s just as likely to happen with buses. And that *is* permanence that rail systems including streetcars absolutely have and that can’t be denied.

The flexibility of bus systems also means that the bus line they use may be rerouted in a way that makes it *more* convenient for them. You are basically arguing that we should lock ourselves into a system even if it is inferior just so that *some* riders who are set in their ways aren’t inconvenienced. That may benefit a few but that obviously is worse for *most* of the riders. Overall it is inferior for the public not just the agency serving them.

The loop service in Portland would be way more useful if it ran more frequently. I’ve taken the FX2 to OMSI Station many times hoping to catch a northbound streetcar, only to see that it won’t arrive for 15-20 minutes. At that point, I just walked the last mile to my destination. Not a pleasant walk, mind you. But ultimately faster.

I actually think the OMSI Station is a useful transfer point between E/W service and N/S service, but the N/S service could use a ton of improvement.