Washington DC mayor Muriel Bowser has announced that the DC Streetcar, a single line of mixed-traffic streetcar along a portion of H Street, will be replaced by a “next generation streetcar.” The Washington Post headline cuts through the spin:

If I could have edited that headline, I might just have said “DC Streetcar to be Replaced by Useful Transit”.

What was wrong with the DC Streetcar? Apart from all the problems of putting transit in mixed traffic while denying it the ability to move around obstacles, the problem was this:

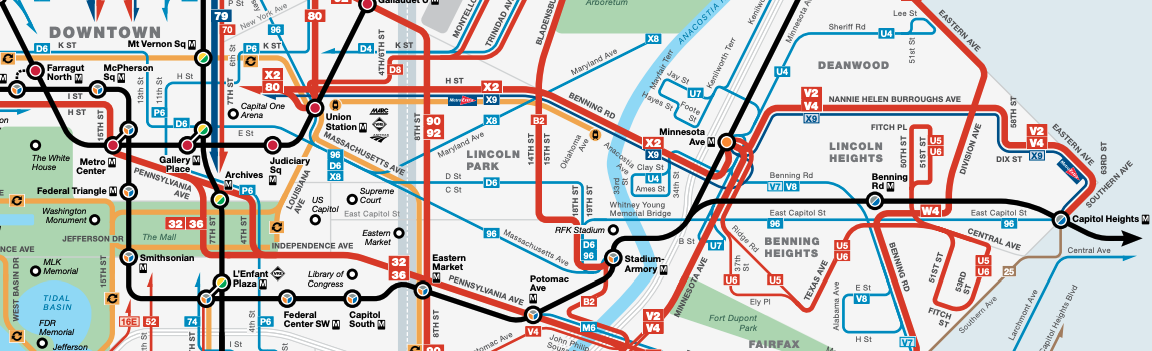

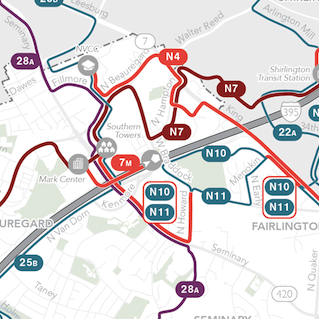

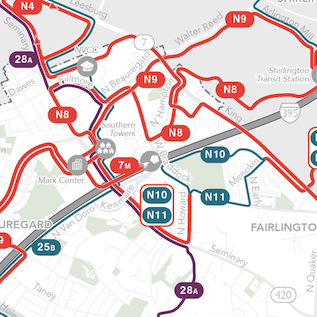

That orange line in the middle of the image, extending from (near) Union Station along H Street to just short of the Anacostia River, is the DC Streetcar. Note that a frequent bus line X2 runs right on top of it but extends further east and west. That’s because the X2, as a bus, is able to operate a complete corridor linking to logical endpoints, and functioning as part of a high-frequency grid. High-frequency grids, which maximize access to opportunity in a dense city, are made of lines that keep going all the way across the grid, so that they intersect as many other lines as possible. One thing an effective grid bus line would never do is end just short of a major connection point, as the streetcar does by not crossing the Anacostia River to at least reach Minnesota Avenue station.

This is one of the key things wrong with most of the mixed-traffic streetcars developed in the US in the 2000-2015 period, and especially those heavily promoted by the Obama Administration. The excitement generated by the development industry, combined with the eagerness to get something started at low cost, led to starter lines that were very short, so they were unable to function well inside of larger grids. The duplication of the X2 and the streetcar is just wasted precious driver time, but the X2 can’t get out of the way of the streetcar because it’s doing important work in a longer corridor, while the streetcar just duplicates part of it. Because the resulting streetcar service was so useless, it never saw the surge of ridership that would form the basis for political support to expand the network.

Across the country now, we’re going to see a divergence in the fates of these little modern streetcars. At this stage, I’m aware of two modern streetcars that I’m really confident will endure: the westside line in Portland and the line in Kansas City, both of which are being extended. Portland’s is, and Kansas City’s will be, long enough to usefully serve a complete corridor rather than just a fragment of it. There are a few other niche streetcars that have strong enough markets. Tucson’s, for example, doesn’t extend across the city’s vast grid but it does link downtown and the University through several walkable neighborhoods, so it makes some sense.

Over time, too, the streetcars that endure are going to be those that gradually transform themselves into something more like light rail, by reducing car traffic’s ability to disrupt the service and widening the spacing of stops. Portland, where the modern streetcar movement was hatched, spent years sending urbanists out across the country saying that “rail is special because it’s permanent.” But fortunately the Portland Streetcar stations weren’t permanent! They were way too close together, and wisely, some have now been removed in the campaign to get the service a bit above its original average speed of 6 miles per hour.

I must admit that when I saw this story, my first reaction on social media was less than magnanimous:

If you weren’t there, trust me. At the major urbanist conferences between 2000 and 2010, few people were saying the obvious things I was saying, namely:

- The permanence of a service lies not in rails in the street, but in the permanent justification of the operating subsidy. That depends (in part) on ridership, which depends on the land use that actually develops around the line, not just what the boosters fantasize. Many US cities facing budget crises now have streetcar operations on their books that compete directly with other city priorities, and if the streetcar wasn’t designed to succeed, they may not win those battles every year.

- Streetcar lines that are too short, and serve only parts of corridors that really need to be served continuously, are net barriers to transit access, reducing access to opportunity. They either require us to take apart corridors that serve more people if they’re continuous, or they require a bus and streetcar to duplicate each other, wasting the precious staff time that is the primary limit on the total quantity of transit service.

This, one of my first really viral pieces from 2009, captures how I was talking back then. I also got into a notorious 2010 fight with Vancouver urbanist Patrick Condon about his vision of covering Vancouver with slow streetcars instead of fast, driverless, high frequency rapid transit. But as always, having been right in the end is never much consolation. Mostly I’m sad that so much well-intentioned energy went into so many projects that weren’t scaled to succeed, and that weren’t sufficiently focused on being useful.

Let’s plan public transit with the goal of being maximally useful to human beings, expanding their access to opportunity. That means designing the right lines first and then picking the technology, not falling in love with a technology and then designing a line around its limitations.