[Updated 2018 Aug 8]

For 18 months, our firm has been working with National Transport Authority of Ireland (NTA) to develop a redesign of Dublin’s bus network. We studied every bus route, drew hundreds of maps of data and ideas, and spent a week locked in a conference room with experts from NTA, the bus operating company Dublin Bus, and staff from the local governments. Once we had a rough plan we spent more months refining and analysing. It’s been a long voyage to this point.

The plan is now released for public comment. The plan revises the entire network, creating a much simpler pattern that people can learn, remember, and explain. A vast high-frequency network, in a spiderweb grid pattern, extends across most of the city, dramatically improving travel time for journeys in many directions.

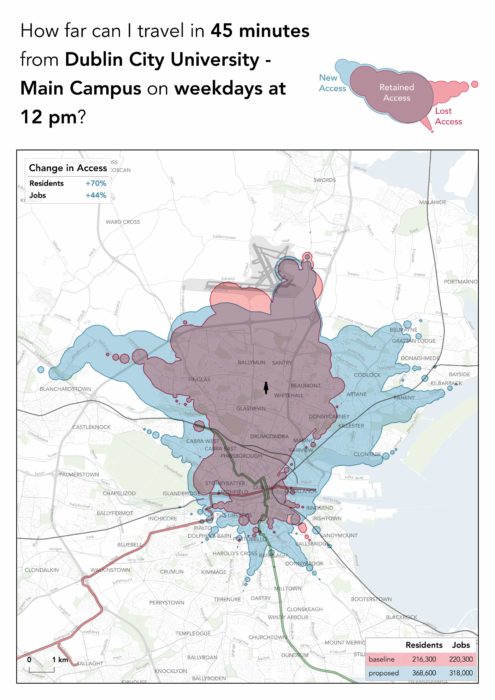

Our key goal was improving access. We wanted to speed up people’s trips, but we prefer to say that we wanted to expand the range of places that could be reached in a fixed amount of time. We wanted people to get to more places, sooner, so that they would have more opportunities in their lives. In short, we want public transport to give people more freedom.

Here is what we were trying to do. Under the plan, in 45 minutes of travel time, a person near DCU gains access to the blue area and loses access to the red area. That means she can get to 44% more jobs and student enrolments (and other useful places). That’s freedom and opportunity! The average result across all of Dublin is a 20% growth in where you can get to.

Under the plan, the average Dubliner can get to 20% more useful places in 30 minutes. “Useful places” means jobs and student enrolments, which are easy to count with Irish data, but of course you can expect similar results for shopping and for all kinds of other destinations that give value to our lives.

There are many ways to explore the new network, including maps, frequency tables for every hour of the day and week, and an interactive map tool that shows where you could go soon on the proposed network, and how you might get there. You can also look at a table showing how the plan affects every segment of every existing route.

But we hope you’ll also try to understand the principles at work. For that, here’s a link to the summary report. Also, don’t be afraid to browse the full report. It is written in plain non-technical English with lots of interesting pictures, and it lays out every aspect of the plan, including the thought process by which it was designed.

The maps are essential of course. Chapter 7 of the full report lays them all out, but you can also see the main ones on the website (click to select a map, then click in the map window to see it fullsize).

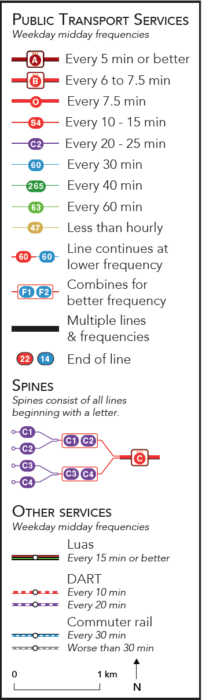

But to understand the maps, you must look at the legend. Our firm’s usual mapping style is dense with information, but therefore contains a couple of things that you need to learn. Most of the early expressions of panic and confusion have been based on misreadings of the map.

But to understand the maps, you must look at the legend. Our firm’s usual mapping style is dense with information, but therefore contains a couple of things that you need to learn. Most of the early expressions of panic and confusion have been based on misreadings of the map.

In our maps:

- Colour means frequency. Red means high frequency, and cooler colours mean lower.

- The colours mean midday frequency; see the frequency table for frequency at rush hour and other times, and see here [select Map 3] for peak-only routes that may be relevant to your area.

- Change in colour may not indicate that a route ends.It often means that the frequency changes but the route continues. Watch the route numbers to be clear, and remember, a spine like “A” is made up of Routes A1, A2, and so on, so where A1 becomes A, the bus keeps going.

A network redesign is both a big idea and 10,000 details. In recent presentations to the media and to local government councils, I focused on the big idea:

- more service …

- to more places …

- so that you get there sooner …

- with a little more interchanging (transferring in US parlance)

But of course the questions and objections were more about the details:

- How dare I take away my direct route to the city? Because it’s really infrequent and inefficient, and we can get you there sooner another way. If we give you more frequent service to a nearby hub, we can connect you to much faster service to the city, so in the end, counting waiting time, you get there sooner. We can also connect you to countless places you can’t get to now at all. In any case, only about 8% of riders all day, and 5% during the peak, lose direct service to the city centre, and not all of those people are going to the city centre!

- How can people change buses, or walk to a different stop in an intersection, when it’s windy and raining? The plan includes good shelter and attention to walking distances at every interchange point. But people change buses in more brutal climates than Ireland’s: Moscow and Edmonton come to mind. Most people have adapted to their climate. They know how to do things outdoors in it, and therefore can work with it when changing buses.

- How will this affect older people and people with disabilities? There is an unavoidable tension between senior and disabled needs – which are much more inconvenienced by interchange – and everyone else. A network designed solely around senior/disabled preferences for minimum walk and interchange is simply too slow to be useful for the rest of the population. Again, attention is being given to making interchanges as convenient as possible, including for people with limited mobility.

- Isn’t this connected to a lot of other things? How can you work on it in isolation? I address that one here.

Whether you live in Dublin or not, I hope you enjoy this work. The full report is the most advanced piece of work our firm has done yet. I can’t speak highly enough of the team at NTA, who have shown clarity and courage throughout this predictably difficult process.

If you do live in Dublin, you MUST complete an online survey. There is a link to it here. Yes, that’s a command. Too often, people take the attitude that public comment is just for show, and that the government is going to do what they want anyway. When that happens, people who like the plan take it for granted, and people who hate it feel like they have to scream to get their point through. So we get nothing but screaming, which makes the plan look like a failure.

On the survey, remember, we value specific comments. If you like the plan but object to a detail, say that. Don’t tell us that we’re stupid because we didn’t get your detail right. There are only so many details we can get right without consulting the public, so that’s the whole point of this public conversation.