Our firm has a fulltime opening for a transit analyst. (Also, watch this space for a senior planner and project manager position to be posted soon!)

Here are the details:

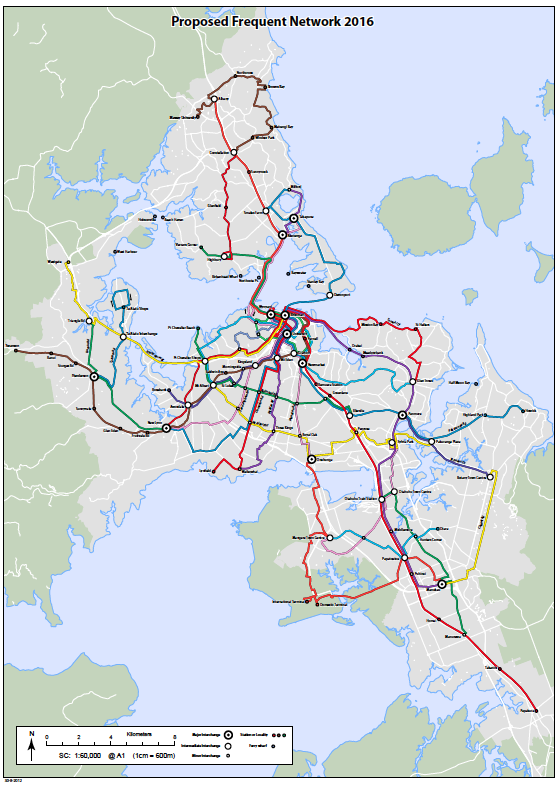

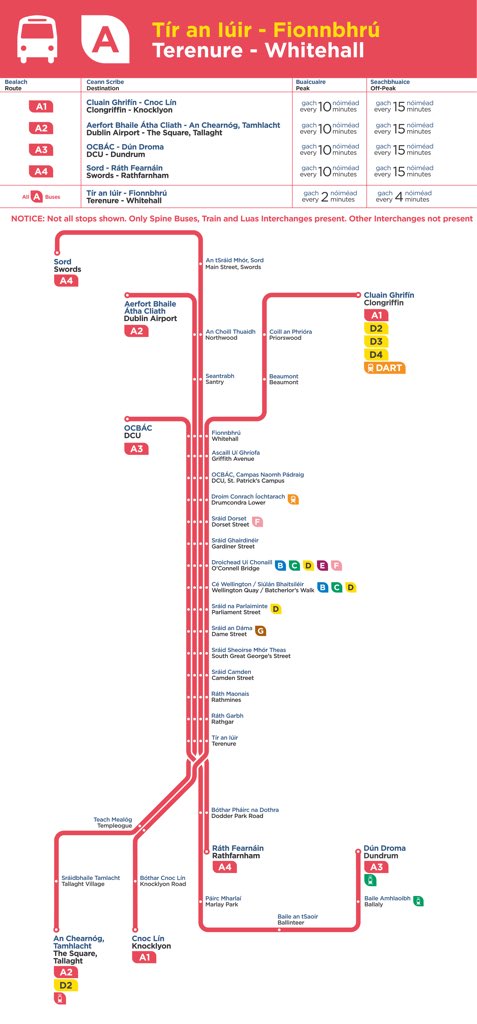

Jarrett Walker and Associates is a consulting firm that helps communities think about public transit planning issues, especially the design and redesign of bus networks. The firm was initially built around Jarrett Walker’s book Human Transit and his 25 years of experience in the field. Today, our professional staff of nine leads planning projects across North America, with an overseas practice including Europe, Russia, and Australia / New Zealand.

You can learn about us at our website (jarrettwalker.com) and at Jarrett’s blog (HumanTransit.org). For a sense of our basic approach to transit planning, see the introduction to Jarrett’s book Human Transit, which is available online. For a typical report of ours, showing some of the analysis we do, see here.

We are seeking a transit analyst based in Portland, Oregon, or Arlington (Crystal City), Virginia. The position offers the potential to grow a career in transit planning. As a small firm, we can promote staff in response to skill and achievement, without waiting for a more senior position to become vacant. Everyone pitches in at many different levels, and there are many opportunities to learn on the job.

Duties include a wide range of data analysis and mapping tasks associated with public transit planning.

Required Skills and Experience

For this position, the following are requirements. Please respond only if you offer all of the following:

- At least two years of professional experience using the skills listed in this section, OR formal training in these skills (such as at a college or university). Directly-applicable coursework is valuable but not essential.

- Fluency in spoken English and proficiency at writing in English. In particular, an ability to explain analytic ideas clearly.

- Understanding of basic statistics and experience with analysis and visualization of quantitative and statistical information.

- Experience in spatial data analysis (GIS).

- Experience working in Adobe Illustrator.

- Experience in cartography, evidenced in at least one mapping sample that is clear, accurate, and visually appealing.

- Availability to start full-time work in Portland or Arlington on before the first week of January, 2019, at least 32 hours per week.

- Legal ability to work in the US.

Other Desired Skills and Experience

The following are desirable but not essential. Candidates with the required skills listed above but none or few of these desired skills are still encouraged to apply.

If you have any of the following skills, please describe them in your application

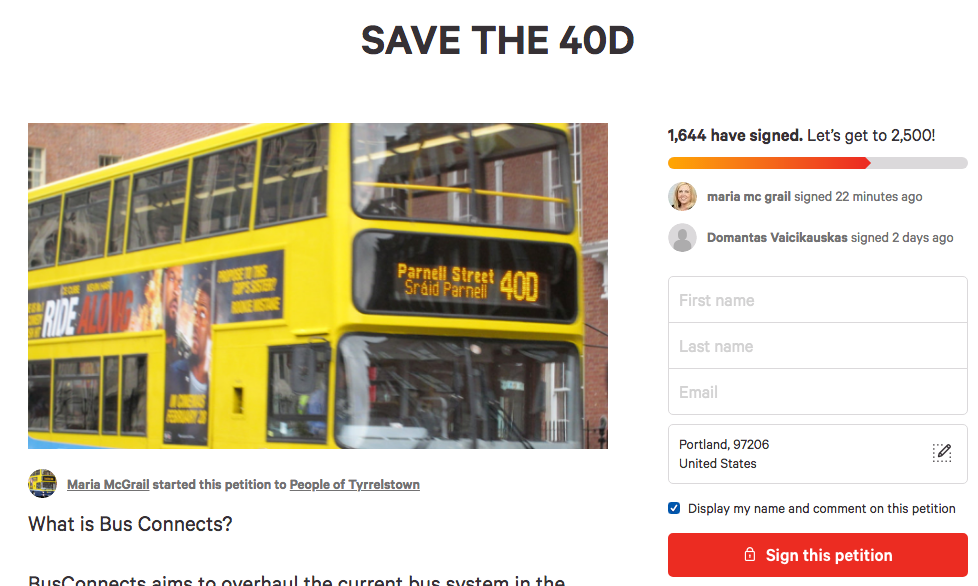

- Experience with public transit issues.

- Experience using analysis programming languages (such as R).

- Experience with qGIS, Remix or InDesign software.

- Experience in advanced database analysis. (Postgres/PostGIS, MySQL, etc)

- Expertise with transit-focused routing software, such as OpenTripPlanner.

- Experience describing issues from multiple points of view, including the perspectives of different types of people, and different professions.

- Graduate degree in urban planning, transportation, or a related field.

- Foreign language ability. Spanish is especially useful but other language skills are valued as well.

- Experience working with minority and disadvantaged communities.

- Experience managing small teams.

- Experience and comfort in public speaking.

Compensation, Benefits and Place of Work

Compensation will depend on skills, but will start in the range of $25-32/hour depending on skills and experience. Raises of over 10% in the first year are typical for excellent work. Our benefits program includes medical, dental, and disability insurance; a 401(k) program; subsidized transit passes; paid sick leave; and paid time off.

This position will require working out of either our Portland, Oregon, office or our Arlington, Virginia, office. JWA does allow employees to set work schedules that include working from home or other locations. This position requires travel, to work with clients directly, at least a few times per year.

How to Apply

To apply, please send the following materials to [email protected] .

- 1-page cover letter, explaining your interest in the position.

- 1- or 2-page resume, describing your relevant experience and skills.

- Links or electronic files for up to three (3) samples of your work. If possible, please include a map, a piece of writing, and a demonstration ofa spatial analysis. (A single sample may satisfy more than one of these requests.)

- Contact information for 1 to 3 references who can attest to your experience with the skills listed above.

- Please do not include any information about your prior compensation.

We will be redacting from your materials any explicit information about your name, race, gender, or sex.

Diversity and Inclusion

JWA follows an equal opportunity employment policy and employs personnel without regard to race, creed, color, ethnicity, national origin, religion, sex, sexual orientation, gender expression, age, physical or mental ability, veteran status, military obligations, and marital status.

This policy also applies to management of staff with regards to internal promotions, training, opportunities for advancement, and terminations. It also applies to our interactions with outside vendors, subcontractors and the general public.

Timeline

The deadline for applying is 11:00 pm Pacific Standard Time on Thursday, November 15th. Submitting earlier is advantageous as we will review applications as we receive them.

We will ask a select group of applicants to perform a simple analysis and mapmaking test on their own, and then to join us for an interview. The test will be assigned on November 20 and due on November 27. We wish to hold interviews (in person or by phone/web) on November 29 or 30.

Thank you for reviewing this listing. Please share it with others you know who might be interested. We look forward to hearing from you.