Amtrak is about to see more Federal funding than it’s had in decades, and is finally in the position to talk about major growth. But their “Amtrak Connects US” vision document is worth reading to notice two things: They continue to face a conflict between ridership goals and coverage goals, and they don’t feel that it’s safe to talk about that openly.

- Ridership goals are served by concentrating good service where there are lots of people to benefit from it.

- Coverage goals are served by spreading service out so that you can say everyone got some, regardless of whether people ride.

Ever since I did the first scholarly paper on this in 2008, I’ve been helping transit agencies face this problem honestly and make clear decisions about it. Pretending that you are doing both just produces confusion and unhappiness, because these goals are mathematically opposite. They tell network designers to do opposite things. Rhetoric can paper over the problem but won’t resolve it.

For years, Congress has berated Amtrak for not being profitable (which would require ridership) while demanding that it run service to every corner of the country (coverage). The high-ridership thing for Amtrak to do, as the report makes clear, is to focus on improved frequency and travel time for trips of under 500 miles, a distance where rail service between city centers can effectively compete with flying between airports, and this in fact is what the plan recommends. But that means the improvements won’t be everywhere.

Yet when it comes to highest-level summary, the report seems pressured to de-emphasize its own recommendations. Here are the seven bullet points that form “Amtrak’s 15 Year Vision” (p9). I’ve labeled each with whether it refers to ridership or coverage.

- Add service to 160 new communities, large and small, while retaining the existing Amtrak network serving over 525 locations. [Coverage]

- Provide intercity passenger rail service to the 50 largest metropolitan areas (by population). [Ridership]

- Serve 47 of the 48 contiguous states, expanding corridor passenger rail service in 20 states and bringing new corridor passenger rail service to 16 states. [Coverage]

- Add 39 new routes, and enhance 25 routes. [Coverage]

- Introduce new stations in over half of U.S. states. [Coverage]

- Expand or improve rail service for 20 million more riders annually—which would double the amount that the state-supported routes carried in fiscal year (FY) 2019. [Ridership]

- Provide $800 million in total Amtrak revenue growth versus FY 2019. [Ridership]

While ridership is the focus of the actual policy, four of these seven points emphasize coverage instead. Three of the them count states, which has nothing to do with ridership or population but does matter when counting votes in the Senate, the US’s ultimate enforcer of coverage-oriented thinking. Amtrak takes pride in serving 46 of the 48 contiguous states, though most rural states are served only by “land cruises,” trains that take 2-3 days to cross distances of over 1000 miles. These provide useful access to some rural towns but are much too slow for travel between major cities, and their schedules — once a day at best — are almost guaranteed not to be going when you need them. Amtrak recognizes that these trains are not a growth market. The future lies in the shorter more frequent links under 500 miles, but the obsession with state-counting in these high level bullet points shows how Amtrak must dodge the obvious in its rhetoric.

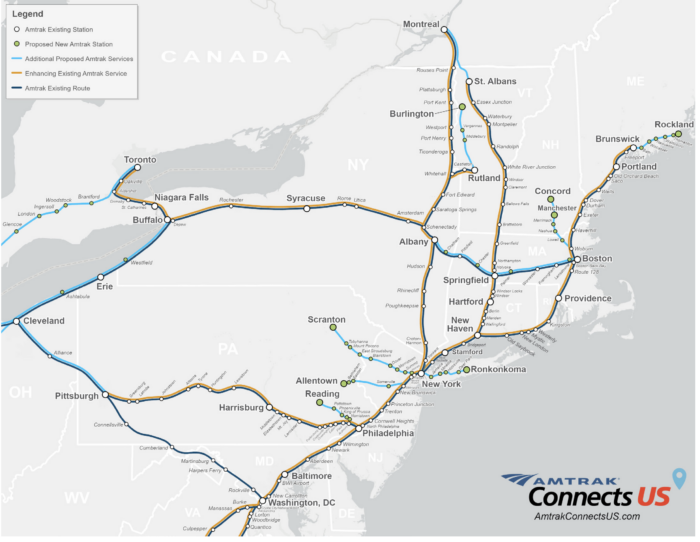

Even more striking, Amtrak does not seem to feel it has permission to draw a map that would show what they’re actually doing. Here’s a bit of the mapping that comes with the document:

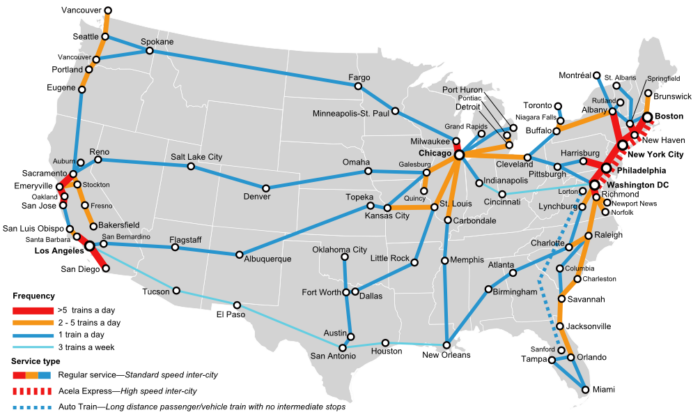

Colors are used here to show where some service is being added, but this map tells you nothing about the actual levels of service on each line. It’s misleading about the pattern of existing service — where frequency is massively concentrated in the Boston-Washington “Northeast Corridor” — and also about the degree to which different corridors are proposed to be improved. In short, it’s a coverage map, designed to emphasize how many places are affected rather than what the benefit is. Meanwhile, a quick internet search turns up a map of 2015 Amtrak frequencies that gives you some sense of how unevenly service is actually distributed:

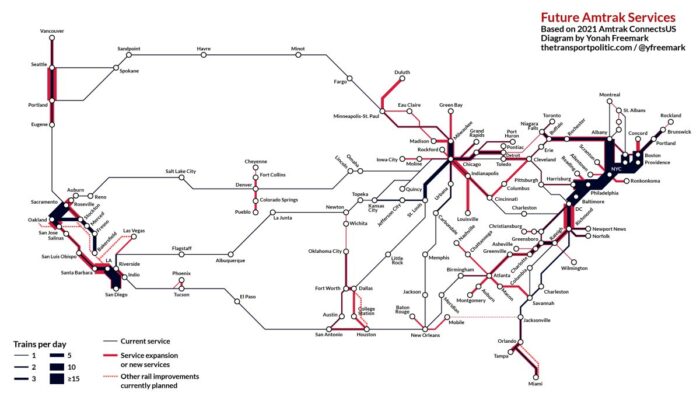

Amtrak wouldn’t draw its own map in this style, so somebody else did a put it on the internet. (This, by the way, is how the idea of showing frequency on local transit maps caught on in the US in the 2000s and 2010s: With encouragement and advice from this blog, impatient advocates drew the maps when the transit authority wouldn’t and this helped give the transit authorities the courage to do it themselves. Today, at least in the US, most major agencies show some indication of frequency in their mapping.) Sure enough, Yonah Freemark has already drawn a frequency based map of the Amtrak plan!

But you won’t find this map in Amtrak’s report, and I can imagine the internal conversation over why. “It will make it look like we hate North Dakota!” Yes, indeed, in the US there are many states with two senators and very few people. Amtrak is planning for ridership, so it doesn’t propose to improve service there. Ignoring North Dakota is an inevitable consequence of a decision that ridership is the goal.

So we get a report that lays out a ridership-driven plan — higher frequencies where there are lots of people — but doesn’t dare say that at the highest level of the document: the bullet points and map that everyone will look at even if they don’t read the text.

I’m not criticizing Amtrak here! This is probably exactly the appropriate framing for their political situation. But you should read this document to practice reading for ridership-coverage tension, to help you recognize when this contradiction is hiding inside your own transit authority’s thinking or rhetoric.