My little stoush with Uber over the last few days — observing that its advertising seems to be presenting itself as a threat to all public transit, including rail — went modestly viral, coming close to a pageview record for this seven year old blog. Uber quickly pulled the offending ad.

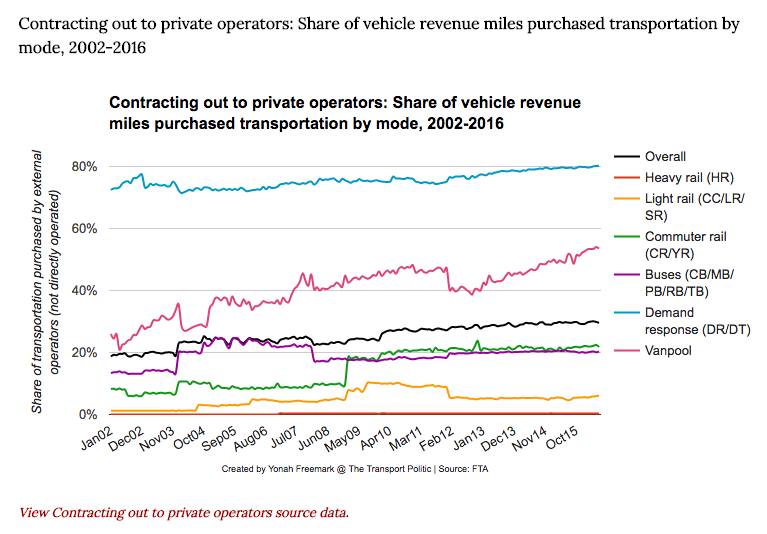

Again, as I laid out here, if Uber and its ilk — collectively and misleadingly called Transportation Network Companies (TNCs) — successfully draw customers away from high-ridership transit services, rail or bus, the result would be several overlapping disasters for our cities, including massive increases in congestion, emissions, road space demanded by vehicles, and inequality of opportunity.

And of course, there will always be people saying that as long as customers want something they should have it, and the consequences don’t matter. This is how we got all of the environmental problems we deal with today, and many of our problems of inequality.

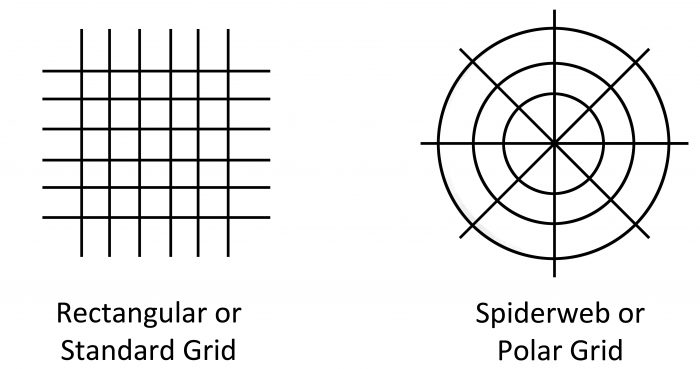

Meanwhile, the resistance is getting traction. A Boston Consulting Group report, flagged in Citylab, argues that autonomous taxis will destroy the passenger rail industry, including urban subways. Anyone with the slightest sense of geometry can see immediately what a disastrous increase in vehicle trips that would be.

Then, Greg Lindsay, a leading observer and commenter on urban tech, noted this:

When @FTAlphaville is quoting @humantransit approvingly, you know the tide is turning, and turning fast. https://t.co/IetlNGUCtv

— Greg Lindsay (@Greg_Lindsay) October 6, 2016

Alphaville is a blog at the Financial Times, usually a pro-business outfit. But they’re not just quoting me; they’re sounding a serious alarm:

At FT Alphaville we’ve questioned the rationality of glorifying a business model (Transportation Network Companies, ‘TNCs’ like Uber) that undermines decades worth of urban planning work focused on encouraging mass transit options like buses and trains, whilst marginalising petrol-guzzling space-consuming single-occupant cars. It seems backward, to say the least.

But the tech world seems oblivious to the limitations posed by urban geometry, seemingly convinced that app-controlled taxis can overcome the space constraints of London Bridge at 5pm more effectively than non-app controlled taxis. Why this should be the case, however, is never clearly explained.

They also cite this paper by Matthew Daus, outlining the numerous dangers of the current prevailing TNC business model, including environmental dangers as well as issues of equality of opportunity. (See his page 20 of his report for the formal litany.) Here’s the critical bit:

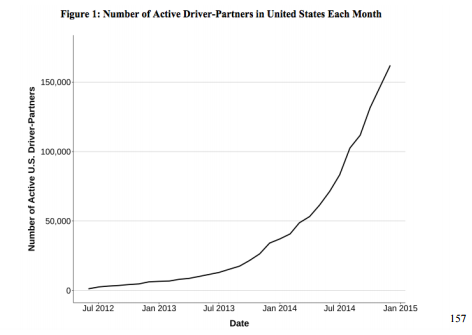

TNCs have grown at a near exponential rate, adding a significant amount of automobiles on the streets of already congested cities. For example, Uber grew from zero (0) drivers in 2012 to 160,000 actively partnered drivers (defined as drivers that have completed more than four trips per month) by the end of 2014 in the United States alone.

As demonstrated in the graph below, the rate of growth has risen rapidly since July 2012:

Uber and its fellow travellers can “grow” like this by continuing to flood dense inner cities with cars, but of course we will run out of space, so that’s not going to continue. The danger is that the attempt to do this will strangle all of our other options, notably public transit, so that once Uber has taken over our streets we’ll have no alternatives, even though they are all sitting in self-made gridlock, shoving cyclists and pedestrians out of the way. This is exactly how cars took over the world, 60-100 years ago.

In other words, this seems to be an issue where only strong government intervention, over the noisy objections of the techno-libertarians, is going to save us.

Of course, there is a free-market solution to this problem, which is to charge for the actual market value of limited urban road space. Once most cars on the road are run by some corporation instead of by individuals, it may be easier to impose the necessary free market forces so that traffic is limited to match the space available. That, in turn, would drive massive demand back to space-efficient modes such as public transit, but only if techno-libertarian public relations campaigns haven’t destroyed those options first, by encouraging apathy about them.

So it’s an interesting time. Maybe the tide really is turning.