Randal O’Toole has made quite a career of being America’s leading anti-planning planning expert, and especially its leading anti-transit transit expert. His biases are obvious but his he knows his topic and can make good points, so he’s sometimes worth reading a little closer. If nothing else, transit advocates need to hear more arguments from outside their own media bubble, just as everyone else does.

Today he has a blog post asking if we are approaching “peak transit.” It’s a concise and readable display of his insights, techniques, and biases. So if you’ve never read O’Toole before, let me take you on a quick guided tour:

“Billions spent, but fewer people are using public transportation,” declares the Los Angeles Times. The headline might have been more accurate if it read, “Billions spent, so thereforefewer are using public transit,” as the billions were spent on the wrong things.

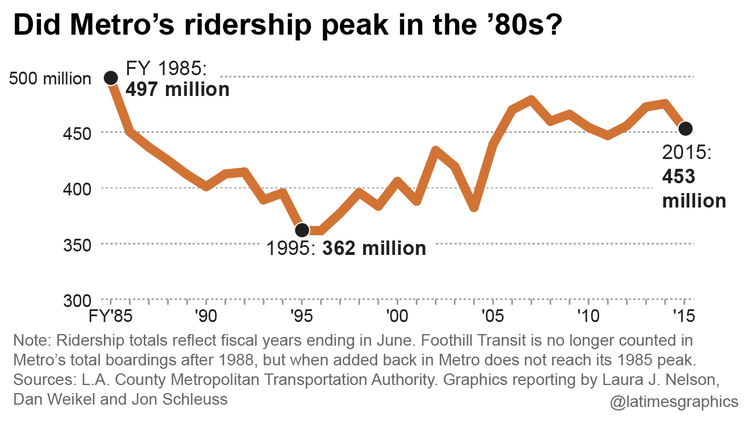

The L.A. Times article focuses on Los Angeles’ Metropolitan Transportation Authority (Metro), though the same story could be written for many other cities. In Los Angeles, ridership peaked in 1985, fell to 1995, then grew again, and now is falling again.

O’Toole nicely summarizes the two fallacies that drove the sadly-too-influential LA Times piece. The first is that Los Angeles ridership is on a clear downward trend based on 2015 data, which is an illusion created by the Times reporters’ selective citation of data. [JW update: The trend is clearer in 2017, which doesn’t change the fact that 2015 data didn’t support it.] The second, more basic fallacy is that short term ridership is the proper metric for judging long term investments. That’s like saying that because the corn you planted wasn’t ready for harvest a week later, it was dumb to have planted corn.

Sometimes O’Toole is Right

But just as you’re ready to dismiss O’Toole, there’s this:

Unmentioned in the story, 1985 is just before Los Angeles transit shifted emphasis from providing low-cost bus service to building expensive rail lines, while 1995 is just before an NAACP lawsuit led to a court order to restore bus service lost since 1985 for ten years.

This is true, especially if you’re careful, as O’Toole is here, not to assert that the lawsuit caused the change. (There are several explanations for why Los Angeles transit leaders started focusing on bus improvements in the late 90s, and rehashing them is not helpful to consensus-building today.) Let’s look again at that chart from the LA Times article.

Los Angeles ridership fell when bus service was being cut early in the rail program, then rose when bus service was being rapidly improved. Since 2005, when the balance of attention on rail vs bus has been closer to equilibrium, ridership has been basically flat, going up and down in a small range that is trivial compared to the great swings of the 1985-2005 period. The little downtick at the end of the chart, on which the Times reporters hang their narrative, is obviously not enough to be significant yet, at least when viewed at this scale.

But this does not mean, of course, that “billions have been spent on the wrong things.” This would require that we share O’Toole’s belief that short-term ridership was the purpose of the rail investments, which it was not. Declaring transit to be failing at goals it is not pursuing is extremely common in anti-transit commentary. Another common example of this is here.

The (Real) Ridership-Counting Problem

Then O’Toole makes another almost-good point:

The situation is actually worse than the numbers shown in the article, which are “unlinked trips.” If you take a bus, then transfer to another bus or train, you’ve taken two unlinked trips. Before building rail, more people could get to their destinations in one bus trip; after building rail, many bus lines were rerouted to funnel people to the rail lines. …

Higher transfer rates are not strictly a result of rail; they can arise from good bus network designs as well. But the “unlinked trips” issue is real. It’s one of those things that makes sense to the transit industry internally but not to the public to whom we have to explain our work.

The problem dates back to a time when completed journeys (“linked trips” in the comically opaque jargon of technocrats) were just impossible to count without expensive manual surveying. This is still the case in many agencies. People flash monthly passes or day passes at the driver, for example, and even if the driver counts this as a pass, there’s no record of whether the rider was beginning their journey or making a connection. As automated ticketing comes in, it is getting easier to count completed journeys. But the transit data world is very concerned with comparability — this is the whole point of the US National Transit Database — and this creates a motivation to use only data that all transit agencies can easily report, even the lowest-tech ones. This is a real issue.

Of course, a rising transfer rate isn’t evidence of failure. But it does distort the real outcomes if a count of boardings (“unlinked trips”) are reported as though they were a count of human beings reaching their destinations. They are not.

Judge by Real Investments, and Real Goals

Transit ridership is very sensitive to transit vehicle revenue miles. Metro’s predecessor, the Southern California Rapid Transit District, ran buses for 92.6 million revenue miles in 1985. By 1995, to help pay for rail cost overruns, this had fallen to 78.9 million. Thanks to the court order in the NAACP case, this climbed back up to 92.9 million in 2006. But after the court order lapsed, it declined to 75.7 million in 2014. The riders gained on the multi-billion-dollar rail lines don’t come close to making up for this loss in bus service.

This is right, too (except for the debatable causal claim of “thanks to,” which I won’t touch). Yes, you have to evaluate ridership in the context of service quantity, and what matters is not what is built but what is operated.

Contradictory Accusations

But then, we get an old O’Toole favorite, that transit agency “officials” are incompetent:

The transit agency offers all kinds of excuses for its problems. Just wait until it finishes a “complete buildout” of the rail system, says general manager Phil Washington, a process (the Times observes) that could take decades. In other words, don’t criticize us until we have spent many more billions of your dollars. Besides, agency officials say wistfully, just wait until traffic congestion worsens, gas prices rise, everyone is living in transit-oriented developments, and transit vehicles are hauled by sparkly unicorns.

Imagine if we had built the Interstate Highway System with this attitude. Oops, we just spent billions on a freeway to newly developing suburbs, but not many people are driving on it yet because the suburbs are still under construction. Surely the O’Toole of the day would have said that those highway planners are fools!

There’s another contradiction here, which pervades all of O’Toole’s work I’ve read. O’Toole can’t decide if (a) transit is a bad idea or (b) transit is just badly planned and operated. If transit is run by idiots, as he often implies, then logically its performance says nothing about transit’s actual potential. On the other hand, if transit is a dumb idea, it would fail even if it were run by geniuses, which he advises it’s not. He can never seem to decide if he’s against transit or against the people making decisions in transit agencies. Logically, these two claims undermine each other.

The Heart of the Matter

We’ve arrived at what’s really at stake here in this obsession with short-term outcomes. O’Toole begins from a deep hostility to the very notion of long-range planning, at least when done at the level of the city or community, and I hear this more and more from “conservative” voices in local conversations. (I put “conservative” in scare quotes because the more I hear the word, the less it seems to mean.) Sometimes I want to get some of these folks (especially older ones) into a room and just ask this: “Close your eyes and visualize your grandchildren, or whatever children are in your family. Are there any sacrifices you’d be willing to make so that they would have better lives, more opportunities, and generally a better world, even after you’re gone, even after you are no longer there to enjoy their gratitude?”

Most writers who self-describe as “conservative” these days, including O’Toole, seem to be starting from a clear no on this question, and presuming the same in their readers. If it doesn’t pay off now, it doesn’t matter. If you think about it, is the world view of the average thrill-seeking teenager, something most of us hope to grow out of as adults.

Transit investments will make no sense to anyone who thinks this way, so the best answer, I think, is to ask my question about grandchildren. If the answer is no, there’s no point arguing.

O’Toole would probably respond that he’s only opposed to government long-range planning, not private-sector or personal long-range planning, but the real horror for him is that as the world is becoming more interconnected, prosperity depends more and more on collective outcomes. Nowhere is this more obvious than in the rising economic importance of cities, the popularity of urban life as expressed in urban real estate values, and the impossibility of managing a prosperous and inclusive city without effective government.

One of the most crticial things governments do, by the way, is involve affected people in decisionmaking. Some folks may look back fondly at times when the private sector did most city planning and city building — as in the 1865-1929 period in the US. Much of the developing world is like this today, and if anyone wants to argue that “great libertarian city” is not an oxymoron, that’s where they’ll have to look for case studies. But these were and are oppressive places for vast majorities who are not connected to the power structure, and the developing-world cities that are trying hardest to improve themselves are doing so through strengthening the government’s role and competence. The notion that a happy dense city can be generated solely from private profit-seeking has been tried, and I suggest you consult your favorite urban novel from the 1865-1929 period for reminders of what that was like. Almost anything by Dickens will do, and so will Upton Sinclair.

Next up, another paragraph with which I can partly sympathize:

A more realistic assessment is provided by Brian Taylor, the director of UCLA’s Institute of Transportation Studies, who is quoted by the L.A. Times saying, “Lots of resources are being put into a few high-profile lines that often carry a smaller number of riders compared to bus routes.”

This is half right. There are lots of great rail projects, but that list does not include projects that can only be promoted by categorically denigrating buses and their passengers, such as many of the new slow streetcars. O’Toole is making a good argument against projects based on technology-fixations, but that’s not an argument against high-capacity projects like the Wilshire subway in Los Angeles, whose purpose is not just to improve transit there but to make many more people want to live and work there. It’s certainly not an argument against Manhattan’s Second Avenue Subway or Vancouver’s Broadway Subway, where the necessary crowds already exist.

The Arbitrary Starting Year, and Other Statistical Absurdities

That, I’m afraid, was the best part. From there on, O’Toole’s post goes downhill. First, we get a pile of misleading but ominous statistics.

Los Angeles ridership trends are not unusual: transit agencies building expensive rail infrastructure often can’t afford to keep running the buses that carry the bulk of their riders, so ridership declines.

Ridership in Houston peaked at 102.5 million trips in 2006, falling to 85.9 million in 2014 thanks to cuts in bus service necessitated by the high cost of light rail;

Despite huge job growth, Washington ridership peaked at 494.2 million in 2009 and has since fallen to 470.4 million due at least in part to Metro’s inability to maintain the rail lines;

Atlanta ridership peaked at 170.0 million trips in 2000 and has since fallen nearly 20 percent to 137.5 million and per capita ridership has fallen by two thirds since 1985;

San Francisco Bay Area ridership reached 490.9 million in 1982, but was only 457.0 million in 2014 as BART expansions forced cutbacks in bus service, a one-third decline in per capita ridership;

Pittsburgh transit regularly carried more than 85 million riders per year in the 1980s but is now down to some 65 million;

Austin transit carried 38 million riders in 2000, but after opening a rail line in 2010, ridership is now down to 34 million.

Give O’Toole credit: When he tells us that ridership “peaked,” he’s confessing that he’s playing the “arbitrary starting year” game. To get the biggest possible failure story, he compares current ridership to a past year that he selected because ridership was especially high then. This is a standard way of exploiting the natural volatility of ridership to create exaggerated trends. Again, the Los Angeles Times article that got O’Toole going made a big deal out of how ridership is down since 1985 and 2006, without mentioning that ridership is up since 1989 and up since 2004 and 2011. Whether ridership is up or down depends on which past year you choose, which is to say, it’s about what story the writer wants to tell.

Then we get a real gem of absurdity:

Even where ridership is increasing, it’s decreasing. After building two light-rail lines, transit ridership in the Twin Cities has grown by 50 percent since 1990. However, bus ridership is declining and driving has grown faster than transit.

Well, of course bus ridership declines when you open high-ridership rail lines. That’s because the rail lines, if they’re well designed, grow out of very high ridership bus lines. Rail replaces those bus lines, shifting a large number of riders from bus to rail. Maybe there is a larger story here about neglect of buses in the Twin Cities, but O’Toole doesn’t make that argument.

Ignore National Statistics

Anti-transit arguments can always take comfort in national statistics about transit, which count all of the rural and exurban population as part of the case for transit’s failure:

Whatever the service levels, transit just isn’t that relevant anymore to anyone. As I’ve pointed out before, more than 95 percent of American workers live in a household with at least one car, and of the 4.5 percent who don’t, less than half take transit to work, suggesting that transit isn’t even relevant to most people who don’t have cars.

Again: National statistics about transit are meaningless, because transit works or doesn’t for entirely local reasons. Most Americans don’t live in places where transit works really well — dense cities, mainly — so of course not many Americans use transit. This says nothing about transit’s popularity in the places to which it’s suited.

Did You Know that You Don’t Exist?

You should also be offended whenever a minority of any kind, including the minority who use transit, is described as not counting as “anyone,” as O’Toole does in the first sentence in that last quotation. Because most Americans don’t ride transit, O’Toole says, transit isn’t relevant to anyone. In case you weren’t offended already, O’Toole hammers it in.

“It’s not the dream of every bus rider to arrive in a bus that was on time, air conditioned and clean, where a seat was available,” the L.A. Times quotes USC civil engineering professor James Moore as saying. “It’s the dream of every bus rider to own a car. And as soon as they can afford one, that’s the first purchase they’ll make.”

Not the dream of most bus riders, but the dream of every single one. Again, if that doesn’t describe you, you aren’t just invisible or unimportant: You actually don’t exist. These are the moments, increasingly common in arguments in our polarized age, when O’Toole reveals that he has no desire to convince anyone who is not already in his cultural camp.

The Nod to Driverless Cars

Finally, there’s the inevitable coda about driverless cars:

Cities that invest in expensive transit infrastructure are ignoring the reality that, long before that infrastructure is worn out, self-driving cars will replace most transit. The short-run issue is that transit agencies that spend billions on rail transit or bus-rapid transit with dedicated lanes are doing a disservice to their customers. The most important thing they should focus on instead is increasing bus revenue miles in corridors where they will do the most good.

I am a big champion of bus investments, but this is the worst possible argument for them, and it’s an especially self-ridiculing argument against rail. High capacity transit lines — including most the rail lines that O’Toole decries — are the kind of transit that is least threatened by driverless cars, because they succeed in dense cities where there simply isn’t room for everyone to be in a separate car, driverless or not. (This is also true of many high-ridership bus services, but not for low-ridership bus services.)

Summing Up

What can we say at the end of such a reading? O’Toole understands transit well enough that he can make substantiated points when he wants to, though he’s also willing to distort statistics with simple tricks like the arbitrary starting year. His suspicion of rail is overly general but overlaps with some valid questions that have been raised by urban progressives like Matthew Yglesias, especially about slow and unreliable rail projects whose usefulness is no greater than that of buses. His defense of bus services, when it’s separated from generalized hostility toward transit or blanket dismissal of anything on rails, echoes the view of many minority and low income groups and also of many transit professionals, including me. Making bus services more useful, after all, is much of what I do as a consultant.

But O’Toole sends constant signals that he does not want to be taken seriously by anyone who lives in, works in, or cares about big, dense cities. He ascribes to government stupidity anything that smacks of the kind of long-range planning that functional and civilized cities have always required, and he also has little time for the public consultation and consensus-building that governments spend so much time on, and which are a key reason they move so much more slowly than the private sector.

In the end, O’Toole sounds like almost everyone who lives inside of echo chambers today, anywhere on the many political spectra, saying this: I, and the people choose to I listen to, all share the same tastes and experience and goals, so the fact that we’re right is just obvious! So, when government disagrees with us it must be stupid and incompetent. The only other explanation would be that there are actual citizens who disagree with us, because they have a different experience or goals, and that these people are asserting their democratic right to influence the government too. No, it can’t be! People who don’t fit my story aren’t “anyone.” They simply do not exist!

This O’Toole quote is amusing when you look at the data:

“Ridership in Houston peaked at 102.5 million trips in 2006, falling to 85.9 million in 2014 thanks to cuts in bus service necessitated by the high cost of light rail”

First, light rail opened in 2004, so ridership actually increased when light rail first opened.

Secondly, in 2006, Houston operated 39,800,000 revenue hours of bus service. In 2013 (latest year in the NTD, but 2014 didn’t see any meaningful changes), Houston operated 41,200,000. So Houston actually INCREASED bus service over this period!

I love the way Jarrett gets out the analytical scalpel and slowly and carefully dissects all the arguments. Everybody should know how to do this, and this post is very good for teaching that.

“Never, ever pay any attention to national statistics about transit, because transit works or doesn’t for entirely local reasons. Most Americans don’t live in places where transit works really well — dense cities, mainly — so of course not many Americans use transit. This says nothing about transit’s popularity in the places to which it’s suited.”

This is such an important point I wish it was a meme all on its own. If there is no transit in 95% of the country, then of course 95% of the country will not use it. And if most of the transit in the remaining 5% of the country is still too infrequent and unreliable to be of practical use, then of course even many people within transit sheds will use other means of getting around!

It’d be nice if this was sussed out a fair bit. Using GTFS data to locate all of the locations with frequent service (obviously this would need some careful definition) in the United States, then pulling those Census Blocks (not just tracts) and looking at transit ridership in those blocks. It would be a lot of work, but then you could really have an interesting look at how popular transit is in areas with frequent transit. Ooh, this block has low transit participation, but maybe that’s because it requires two transfers to get to the rest of the frequent network. Ooh, this block has great transit participation, but that’s because real estate is too expensive to park a car there… Anybody about to start work on a PhD and need something to dig into?

For another beaut example of the ‘only X per cent’ meme: Newcastle, Australia, population 400,000, has (or had) a small but reasonably useful suburban/regional train service (2x30km lines with half-hourly service). Recently the last 5km of the line at the city end was cut back to expedite inner city property development. During the decade or so that this proposal was debated, the authorities that wanted to the cut the line were very fond of producing reports stressing that Newcastle’s train service carried ‘only’ 20 per cent of Newcastle’s transit ridership. Desired inference: getting rid of it didn’t really matter.

But of course the train service carried ‘only’ 20 per cent of the city’s transit ridership – because the city has many bus routes but only two train lines. The test of how useful a service is is how well it serves *the people that it serves*, not the rest of the world who have nothing to do with it. That principle was a cognitive step too far for the Newcastle anti-rail crew.

“Most Americans don’t live in places where transit works really well — dense cities, mainly — so of course not many Americans use transit.”

Can you check that statistic, please? According to the Census Bureau, the weighted population density of the United States is 5,369 people per square mile. In other words, the average American lives in a census tract that is dense enough to support regular bus service. As Paul Krugman described it,

“First, although America is a vast, thinly populated country, with fewer than 90 people per square mile, the average American lives in a quite densely populated neighborhood, with more than 5000 people per square mile. The next time someone talks about small towns as the “real America”, bear in mind that the real real America — the America in which most Americans live — looks more or less like metropolitan Baltimore.”

Of course, census statistics don’t tell us if those dense census tracts are located along corridors that are easily served by transit routes. Even so, I think more Americans than you suggest are living in places where transit can potentially work well.

Laurence

I’m not sure how you define a density as “supporting” bus service. The average density that Americans live at, which you cite as 5369 persons/sq mi, works out to 8 persons/acre, and depending on your favorite household size that can’t be more than 4 dwelling units/acre, i.e quarter acre lots in suburbia.

That kind of development “supports” bus service in the sense that some of it has bus service, but that service isn’t usually doing very well in ridership terms.

There are also all kinds of problems with average density in discussions of transit, because transit responds to such microscopic patterns of demand. It matters whether an apartment complex is right at a stop or 1/4 mile away, but it is probably in the same census tract regardless.

What’s more, density is only one of the necessary conditions for transit to succeed. Walkability and linearity, in particular, have veto power over transit’s success at any density. Details here: http://humantransit.org/2015/07/mega-explainer-the-ridership-recipe.html

Jarrett

Thanks Jarrett, those are good points for the most part. Your density calculation assumes that 100% of the census tract is residential land. But some of the land is occupied by streets, schools, parks, shopping, warehouses, etc. At moderate density around a third of the land is residential, so 5,000 people per acre translates to 8 dwellings per net residential acre. If the residential acres are clustered rather than evenly spread across the land — which is usually the case thanks to zoning — then that density is at least somewhat transit supportive.

Correction: 5,000 people per square mile translates to 8 dwellings per net residential acre.

The problem is that the average is not a median. You get to this average by taking the weighted mean of 70,000/km^2 census tracts in Manhattan and 500/km^2 census tracts in exurbia.

You are absolutely right, Alon. According to this handy calculator (http://fakeisthenewreal.org/by_density/), the median-density block group in the U.S. is 2,500 people per square mile. That’s 3-4 dwellings per net residential acre and not dense enough for regular bus service.

About 30% of the U.S. population lives in census blocks denser than 5,000 people per square mile. That’s definitely less than “most” Americans, but on the other hand in 2016 that’s probably more than 100 million people.

first of all talking about median would be more useful, also even if the level is still enough to support basic bus service on shared roads that doesn’t make buses competitive with private cars for those who can afford it, because cars are faster (no stops) and always there, so of course only the captive riders are going to use the bus.

As the density increases, also traffic congestion increases and the story changes.

Weren’t the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles? Wouldn’t that overflow to the following years until they get to the more “normal” ridership numbers appears.

Ethan Elkind has a correction on the Olympics point. Apparently, fare cuts explain the 84-85 peak better than the Olympics do. I’ve updated post.

http://www.ethanelkind.com/los-angeles-transit-ridership-to-trend-or-not-to-trend/

It seems that Metro has a problem. Either they know that ridership is on the decline because it actually is on the decline or they don’t know the first thing about what’s going on because they’ve stated publicly that their ridership is on the decline and that they need to to better. Neither view is especially encouraging.

An excellent learning tool. There’s not enough skepticism on both sides. Advocates over-promise and opponents fit the data to their case. I distributed it widely.

Great analysis on O’Toole.

The data O’Toole and his counterpart Wendle Cox use is manipulated to meet their agenda. However, as Jarrett has said, they do bring up issues that transit professionals need to address, and one of them is the lack of transit use in America.

Transit professionals can come up with all the excuses they want, and say we are building for the future. But this does not mask the issue that public transit use in America sucks, and has been in decline for decades when looked at on a per capita and mode share basis.

I also think that it is a little bit of a cop out to say that it is not fair to look at national numbers in transit. If anything, it is important, because it sheds light on the glaring lack of transit in most of America.

While something like 50% of Americans live within walking distance of some sort of transit. This number increases to over 80% in Canada, and to over 90% in Germany, including rural areas. 12% of work trips in Canada are made on transit, including the rural areas in that stat. So why is a country wide stat for the USA not valid? Again, it just shows how much work must be done in the USA to build viable transit again.

The stagnant transit mode share in the USA, country wide and in individual cities which have had massive transit expansion, is also a huge concern planners have to address. Planners have to advocate that we are never going to see a turn around in transit use, if quality public transit is not provided to all areas of metropolitan areas. This includes properly integrated services. And the lack of mode share improvement is a serious issue when looking at peer countries. In Canada and Australia, for example. Cities which have opened new rail lines with the accompanying bus improvements, have seen great mode share growth. It is odd that almost no American city, including Portland, has been able to pull this off since the early 1980’s.

So yes most of what O’Toole writes is questionable. But the one good thing is that he does make transit planners have to address the vary issues they should be talking more about and advocating for.

LA, Portland, Salt Lake City, and many other cities can build all the rail they want. Until you can get a bus at midnight on a Sunday that comes more than once an hour on the extreme outskirts of these cities. You will never see a turn around in the cities listed, or any others in America. And that does need to be addressed, whether O’Toole writes about it, or someone else with much less of a bias does.

No country sprawled like the US.

You’ll have to fix absence of transit investments AND bad city planning at the same time to actually see change.

Even where ridership is increasing, it’s decreasing. After building two light-rail lines, transit ridership in the Twin Cities has grown by 50 percent since 1990. However, bus ridership is declining and driving has grown faster than transit.

Yeah, I agree, that is just absurd. The author does the right thing in focusing on transit ridership, notices an increase of 50%, then says it is a failure because bus service is down. While you are at it, tell me whether service from blue buses are down or not. This is actually a variation of a weak argument used by transit proponents to support a particular mode. Add a streetcar that replaces the most popular bus service, cancel the bus service, then proclaim victory when the streetcar carries a bunch of people. Sorry, no. You need to look at the overall network. In the case of the Twin Cities, and overall increase of 50% in transit use is a stupendous achievement.

But even that is a just one metric. Infatuation with ridership misses the point. Of course you want an increase in ridership, but you also just want to build a better system. There is a very scenic road outside Seattle that is gravel right now, and the Forest Service, in cooperation with the state and other agencies, is in the process of replacing it with pavement. This make it much nicer for everyone who hikes in the area. But no one will care, nor will anyone focus on “ridership” in the area. They will focus on the fact that it is a much nicer road! The same is true for every road improvement. There is rarely a discussion as to whether it has lead to an increase in driving, but whether it actually works better. In the case of transit, of course you want both. Most of the time, unless you cut service hours (as L. A. has done) you get both. But if you see a minimal increase in overall transit ridership but those riders can all get to where they want to go much faster, then that is a good thing.

O’Toole got his start due to a poorly thought out New Urbanist project in the Oak Grove area of Clackamas County. It was a community built around the Portland Traction interurban service that had been discontinued in 1958, but was only tapped by a mediocre bus service. The public uproar launched him as an opponent of long-term planning.

His discussions and most journalistic efforts miss another statistical issue that results from traditional transit data gathering. Passenger miles trend with only a partial relationship to unlinked trips, but they are hard to calculate. With the introduction of APC’s we can easily see this route by route, mode by mode, etc. In “Denver” for example, unlinked bus trips can be compared with unlinked rail trips, but the rail trips are longer than on Local buses and were shorter than on Express buses. The amount of work done by one unlinked trip is not the same as the other unlinked trip.

As time is money, longer rides cost more to provide within a mode. I experienced this first hand in Edmonton during one of its booms. Ridership was increasing overall, but it was growing most on long express bus routes. These not only were on the road longer, but made for miserable working conditions for operators, contributing to a driver shortage. The problem was “solved” by reducing night service to get “hours” for the new peak service. Unfortunately, the cost of carrying an unlinked trip in the peaks is not the same as carrying one in the off-peak,

These unexamined differences between one unlinked trip and another sometimes end up as an increase in flat-rate fares caused by increasing trip lengths or increasing peak to base service ratios, further clobbering short-haul ridership. That happened in Edmonton and I suspect it has happened elsewhere. Journalists and decision makers rarely comprehend this.

The mathematical and geometric required density for high ridership transit can be encouraged by service that is frequent and available nearly 24 hours per day.

Valuable transit doesn’t have to be on rails. It can be bus service with supporting infrastructure and service levels that attract riders and density follows (how long is the lag?) because people want or need to be close to useful service.

Maybe Metro’s changing bus routes undermined the message that some locations were valuable to live or work in because you could depend on service that allowed freedom.

The permanence of rail is important because it withstands the changing winds of politics and the economy whereas bus service is easy to discontinue.

The public transit critics usually fail to acknowledge the total and ongoing cost of roads and refuse to allow the necessary time for density to follow useful service.

Metro’s leadership has to answer for results of changes that they probably didn’t want. The build-out of rail is insurance against shortsighted thinking.

I don’t think you can actually encourage density with good service unless you force everyone to have good service and pay for it themselves with a tax proportional to property surface. Good luck getting approval for that, although it would definitely kill the sprawl in a short time.

They should actually do that with sewage and municipal roads though.

If people want to live close to the good service because they want it, that means that car traffic is already bad enough to want the service (on bus lanes) in the first place, and that means the density is already making it worth the cost. The egg comes before the chicken imho. Do proper urban planning in conjunction with good service, or you’re wasting money.

Our experience with the SkyTrain Expo Line in Vancouver proved that you can build the density in key station locations after the service is established. That one line is still generating billions every year in development value even after three decades with no direct tax or floor area surcharge applied to the development.

The urban design and architecture may be subject to heated critiques, but the fact that rapid transit stimulates the local economy like few other elements can is undeniable. In fact, the total value of the development is probably 20-30 times the cost of the transit service.

When I read about Randall O’Toole and Wendel Cox I always laugh with the above in mind.

My favorite Randal O’Toole comment is one I think is quite revelatory to his thinking and biases. Following Hurricane Sandy hitting New York and the subsequent damage to the city’s subway system, he proposed (seriously!) that New York just let the subways rot and instead replace them with underground electric-powered buses.

http://ti.org/antiplanner/?p=7092

There are two alternatives to rebuilding the subways. The drastic alternative is to simply let the city fend for itself without subways. A more realistic alternative would be to convert the subways into underground busways. Electric buses could move just about as many people as the subways do with far less infrastructure.

Sure, underground electric busways are a great idea to replace the NYC Subway. Except, instead of rubber tires, let’s use steel wheels. And instead of buses, let’s link vehicles together and call them trains.

He can’t resist the opportunity to take a shot at rail transit, even in this absurd circumstance. It’s a window into his thinking.

Vancouver has had driverless trains for 30 years and it’s proven to be a surprisingly successful system. Paris’ RER has one or two lines with automated train control. The London Underground and Toronto subway are seriously considering introducing driverless technology because this permits greater frequencies at very reasonable costs while maintaining safety.

I just don’t see this as easily and cheaply implemented with buses, especially when the rail infrastructure is already in place that will require only moderate change.

This article is great. Miami’s MPO and commissioners and FDOT have fallen in love with one or two reports written by O’Toole many years ago that claim—essentially—that the only way to protect freedom and liberty in America is to build toll lanes on all highways and wash our hands of the rest of transportation. Those reports fail to take into account the massive subsidy and regulatory preference that sprawling development has and does receive, much less the externalities associated with auto-oriented development (poor health, climate change, in liveable cities, loss of freedom for children and elderly, etc.).

@Mike

As you undoubtedly know, I agree with your point that people who use transit as their main mode need to be able to rely on it at midnight on a Sunday. The part of your thesis that I don’t follow is the role of the transit planner in making that happen.

What I mean by this is that I believe that the availability of services is more dependent upon the availability of resources than it is by their allocation. In auto-dependent North America where we “invest” in roads but “subsidize” transit, we are a bit ham-strung by our political situation, and I don’t clearly see how transit planners are the ones to lead us out.

I did catch your line: “Planners have to advocate that we are never going to see a turn around in transit use, if quality public transit is not provided to all areas of metropolitan areas.” Are you saying that planners need to use geographic reasoning to make the political argument for service expansion?

In light of widespread disrespect of transit, why use the ‘all areas of the metro argument’ instead of advocating “in areas of high daytime ridership, we should increase evening and weekend service”? Or “in places where transit is doing OK for ridership despite marginal service, we should increase the frequency so that it can do well”?

It’s not as strong in old Europe, but still. I notice it more since I moved to Montpellier, a 420k urban zone in southern France. The other day, I went to a restaurant with colleagues after work, and asked one of them to “drop me at the fork tram station”. I wanted the fork station to double my chance of having one tram soon.

At office time, this station has 1 tram every 6 minutes. At 22h00, it was down to 1 every 30 minutes. Next time we’ll go to restaurant, I’ll take my car, I’ve been very lucky to wait only 4 minutes.

Montpellier is a fast-growing area, very attractive for IT, and local infrastuctures do not follow. The worse is the water situation, but transports are not far behind. I had to move there last summer, and had tough time finding a well-placed flat. The “Sabines” area seemed interesting, but visiting it on rush hour was like a cold shower. Scarce overcrowded trams, and roads you can safely cross by foot, as cars are all stopped. And there is nearly no shop in the area, and they build more & more flats for newcomers as me. And no increase in tram or bus frequency is forecasted, and the road network has no improvement forecasted either.

All the money is diverted in the new high-speed train line, that will avoid the center town, allowing the parisians to reach Barcelona in 10 minutes less than before, and wrecking up 90% of people living in Montpellier. I’m part of the 10% living in the good(south-east) part of the town, but still. All 4 tram lines currently lead you to the current center-town train station. Maybe they will make the line 1 longer to reach out the new train station. A bummer.

With a fraction of the cost of the new high-speed train line, you could have ublocked seriously the Sabines area, whatever the solution choosen, road for cars, tram, bus. But, seen from Paris, nope. The issue you raise is not far from what Jarret spoke about not long ago : thinking about people not in the room. The parisian planners obviously did not.

that’s what the French get for being a centralist country.

Centralization has good points, but also bad points, as you rightfully pointed out. And it sometimes is a big problem, like in my example.

But centralization or not, when you don’t take people not in the room in account, you’re not doing a proper job. If the rail line had been designed only for the interest of locals, with no consideration for long-range travel, it would have been bad as well. And the old tram line, drawn only by locals, carefully avoids to link the airport. Because taxis.

The problem is less the level of decision, than its ability to take in account the other levels.

was the old tram line funded only by locals? If not, that means the upper level public entities didn’t use their influence properly to achieve best bang for bucks, so they wasted their tax-payers’ money.

In a bottom-up approach that requires financing from upper levels, the upper levels have lots of influence because they can deny funding.

They should deny funding to tramways that purposefully cut short before reaching a close-by airport that has a future.

In the case of a high-speed rail line, the central decision maker can ignore the locals since they don’t actually need their money, unless forced to consult by the laws. Centralist systems by nature don’t have strong laws that protect local interests though. If everyone actually cared about local decision-making, maybe they wouldn’t support a centralist system in the first place.

@Shaun,

About planners:

Everyday planners use excuses like density, housing types, and poor planning decisions to basically keep the status quo about poor transit going. I remember in planning school when I was interviewing planners in Balitmore on a school trip. They basically said they were writing off entire areas of suburban Balitmore as never being able to support transit, and just accepting the car would be the only mode of transport. We are talking about areas that in similar world cities have frequent transit. Instead of looking at solutions and thinking outside of the box. They were just keeping the same status quo going. This was a chance where planners could have made a difference.

Of course you are never going to get buy in for more transit funding, if you keep telling people their area does not deserve transit until they are all living in 40 story towers. Of course you are never going to get more funding, if you keep advocating for not providing good transit to everyone. Planners have the chance to educate and show best practices. Some planners have done a great job of making transit great, such as the post war planning in Toronto.

About LA and the focus on high ridership routes. That is basically what LA has been doing, and it does not seem to be working out that great, if we look at the ridership numbers.

Just like building one mega rail project is not going to fix transit, because most people are not served by that single line. The same is true with buses. Providing great service, or late night service on a few bus routes is going to do nothing, because 90% of the population does not live on those lines.

The car can get you anywhere, and transit must do the same. And it is only in cities where transit does take you wherever you want, that transit use is high, and mode shares are increasing.

America has a transit access and supply crisis. And until that is addressed, transit use is going to continue to stagnate and decline.

Isn’t it the case that, for the most part, the areas of the US today with density, diversity of land usage, and walkability which support effective transit are the parts of cities which were developed prior to that 1929 cut-off, zoning and other municipal planning codes? Pre-1929 city planning/building wasn’t 100% private sector, but it was more private sector than today and it can count the vast majority of durable urban areas, while the post-1929 era, with greater state involvement in urban planning/construction, can largely only count auto-oriented suburban sprawl, slum clearances for towers in the park. State involvement of course is not intrinsically anti-urbanist: that for 70 or so years state preferences in urban planning tended strongly toward anti-urban is something of an accident of history (most of which boil down to those who called themselves progressive for the first half of the 20th century in America essentially hating the chaos of urban living).

Thank you Jarrett for this important and intelligent rebuttal.

I, too, agree that the term “conservative” is too broad to accurately portray a particular political and economic view of the world. At one point the root “to conserve” was a phrase best applied to the preservation of sensitive ecosystems, or to hold back a portion of one’s finances from frivolity, or to save a portion of a nation’s resources for future generations. All of which are the hallmarks of sound planning. Today, being conservative could mean you hold radical social and ethnic views, or believe that slashing public budgets to eliminate deficits and lower taxes despite the economic damage will lead to some kind of trickle down payback that, despite the long ideological rhetoric, is short on real evidence.

Nonetheless, O’Toole’s meme follows a path well-worn by fossil-fueled climate change deniers, and leads to conclusions based on selective and cherry-picked data. His ‘up is down’ compartmentalized reading of clear graphs and plain data sets purposely ignores long term trends. This is a particularly common technique that also emphasized that a global warming “pause” supposedly proved that global warming either didn’t exist, or had stopped, all the while ignoring the important context of warming over centuries.

With this kind of thought process the battle lines are drawn in the “war” between evil socialism (read: public sector initiatives for the common good) and “free enterprise” (read: private sector individual advancement). Where it gets really fuzzy is when pundits like O’Toole talk about money but in fact actually ignore it, notably in the form of public subsidies and external costs. What is the overall tax-supported capital and operating costs of the US interstate highway system?

Perhaps it’s best to redirect the conversation to examining the actual return on investments. In some cities the return on spending on a decent public transit system can realize a permanent operating cost recovery of 50% or more through the fare box especially if married to a land use response, and lower expenditures on roads and pollution and car accident-related costs. The individual’s cost savings by not owning a car in the presence of good transit could be termed the result of a “conservative” measure. Freeways do not have any operating cost recovery mechanisms unless they are tolled, but then again the tolls usually come off when the capital costs (and if one is wise, the debt servicing cost) are paid off while the operating costs and any build-up of replacement reserves are not acknowledged by people like O’Toole. There are very good reasons why the vast majority of roads remain in the public realm, but public officials could allow themselves be motivated a bit more by a conservative ledger-balancing attitude to seek more return on this massive expenditure and to evaluate the return in light of the return on transit either in a cold monetary calculation, or also in terms of social and environmental costs and benefits.

Thank you for taking the time (and I am sure it was time consuming) to explain unlinked trips to your readers. This is a concept that dogs transit folks continually and was one of the concepts that I really hated about transit.

I remember interviewing the manager of Calgary Transit in the 70s about their upcoming LRT line. He said the trip time for buses on the McLeod trail (I hope that is correct) had more than doubled and they weren’t buying buses to transport rider but “to store them.” i thought that was one of the best ways of expressing the problems created by increased congestion.

Todd Litman, a transportation planner based in Victoria, BC, had a recent thrust and parry session with Wendell Cox, O’Toole’s partner in arms. Litman placed an extensive piece on his Website along with links to his original report, Cox’s rebuttal, and Litman’s well-referenced and even-handed response.

One quote:

Cox lacks a comprehensive vision for more efficient and equitable cities. He prescribes only one policy, reducing restrictions on urban expansion, but fails to show how this could solve urban problems such as traffic and parking congestion, accident and pollution problems, and inadequate mobility for non-drivers. Cox is out of synch with changing consumer demands and professional practices which emphasize more comprehensive analysis and integrated planning.

Sound familiar?

http://www.vtpi.org/PPFR.pdf

Thank you for that link to Mr. Litman’s rebuttal.

In just a few words you succinctly described a phenomenon I’ve been thinking and writing about for a long time, but not nearly as clearly:

as the world is becoming more interconnected, prosperity depends more and more on collective outcomes

and yes, this is the crux of the argument about small government and “big government.” It’s more about the nature of an interconnected economy that operates within an increasingly interconnected world.

Transit of course is one of those elements in conurbations.

2. with regard to the Mike and Shaun thread, I believe that only when we get transit right in the places where we know it will work, with the right density, destination, and frequency conditions, can it be extended further. Many locations within a metropolitan are inefficient to serve with frequent transit.

That being said, I argue that setting network breadth and depth LOQ/LOS metrics is a way forward in trying to get there.

But speaking of giving great service to all areas of a metropolitan area, when the new light rail line opened in St. Paul, a newspaper in St. Cloud Minnesota editorialized how it was a waste because for the same amount of money you could build many more miles of commuter rail to serve St. Cloud, even though there would be something like 1/8 or fewer the number of daily riders for said commuter service.

Of course, that doesn’t make sense financially or service-footprint wise. Different parts of a metropolitan area or region are served differently depending on the spatial, density, and interconnection conditions.

Jarrett, did you see (O’Toole’s bosom buddy) Wendell Cox’s follow-up piece celebrating the idea that the Times article underreported the horrible drop in ridership caused by the focus on rail and how “The principal purpose of the rail system was to increase ridership…” ? Cox seems happy to make the assertions that O’Toole avoided.

http://www.citywatchla.com/index.php/the-la-beat/10555-just-how-much-has-los-angeles-transit-ridership-really-fallen

It’s kind of funny that his article doesn’t mention that the analysis he is touting is by a co-author of his for several articles. He also doesn’t mention that the analysis is not actually out there randomly in public but only available on his own website.

What exactly is the long term goal?

Metro’s Long-range transportation plan generally talks about “mobility” and better quality of life, but the only defined elements in the opening specifically stated are: “everyone wants faster travel, more transportation options, and less traffic” and “a balanced transportation system that will provide new options for travel”. The document acknowledges that population and job growth are clogging the freeways, and the solution it gives is an expanded system of carpool lanes. So faster travel by car seems to mean carpooling. Other “faster” initiatives are subway, regional rail, and rapid bus lines. “More transportation options” and “new options for travel” seems to be more areas receiving these things and bikeways and pedestrian paths. “Less traffic” seems to be a desired result of drivers switching to these other modes. So it all adds up to more people being able to access these various non-single-occupancy-vehicle modes. Because people have the option, it doesn’t mean they will all take it. So it’s options for access and thereby mobility. Which Jarrett prefers to talk about as “abundant access.” Although Jarrett’s version specifically says “most competition to cars” and the LA Metro plan only implies the competition of its system enabling people to choose to not drive individual cars.

Thank you