Tuesday, March 16, I’ll be on a Portland Forward panel exploring how to revitalize Portland’s central city. (I’ll probably try to broaden the topic a bit.) It’s a panel of experts in several fields, so I have to represent all of transportation myself. Should be interesting. Details here.

Author Archive | Jarrett

Yikes! I’m in Wikipedia

Well, I certainly didn’t expect this, and I don’t know who wrote it. Thanks to whoever did!

As of right now (March 10, 2021) it has several objective problems, including fanboy diction, some confused writing, and an emphasis on obscure citations instead of major ones.

If you want to wade into editing it, I’m happy to provide facts but not bias.

Fixing US Transit Requires Service, Not Just Infrastructure

TransitCenter has a new video and article with some powerful images saying what I say all the time: If you want to transform public transit for the better in the US, there’s useful infrastructure you could build, but the quickest and most effective thing you could do is just run a lot more buses.

(Remember, US activists: Don’t just envy Europe; start by envying Canada. The average Canadian city has higher ridership than the most comparable US city, not because they have nicer infrastructure or vastly better land use, but because they just run more transit.)

TransitCenter’s work uses access analysis to show what’s really at stake. Increasing bus service by 40% (an aspirational number that still wouldn’t match many Canadian peers) would massively expand where people could go, and thus what they could do.

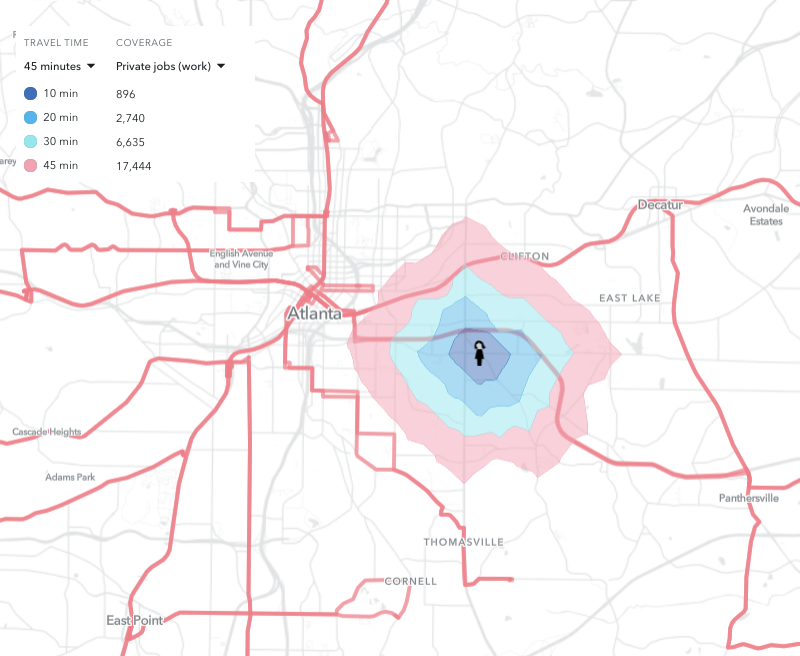

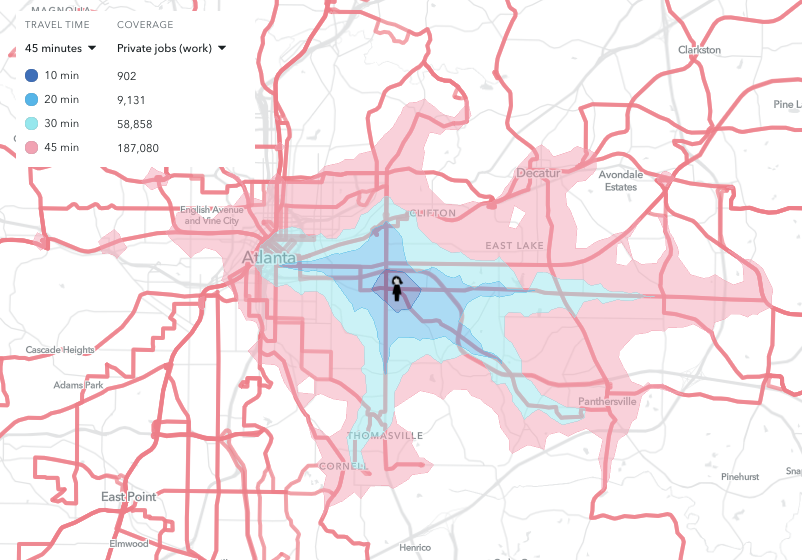

For example, here’s how 40% more service would expand where someone could get to from a particular point in metro Atlanta. (The concentric colors mean where you could reach in 10, 20, 30, or 45 minutes, counting the walk, the wait, and the ride.)

With a 40% increase in service someone in this location can reach ten times the number of jobs in 45 minutes. (These analyses use jobs because we have the data, but this means a comparable growth in the opportunities for all kinds of other trips: shopping, errand, social, and so on. ) I would argue that someone at this location would be 10 times as free, because they would have 10 times more options to do anything that requires leaving home.

The transportation chatter in the new administration is about infrastructure, partly because there’s lots of private money to be made on building things, and because building things is exciting. But if you want to expand the possibility of people’s lives, and seriously address transport injustices that can be measured by this tool, don’t just fund infrastructure, fund operations. Just run more buses!

Is Covid-19 a Threat to Public Transit? Only in the US

Jake Blumgart has a must-read in CityMonitor pointing out that in most wealthy countries, Covid-19 has raised few doubts about the future of public transit, nor have there been significant threats to funding.

City Monitor spoke with experts in Canada, East Asia, western Europe and Australia about the impacts of the pandemic on public transportation. None feared that systems in their nations would be deprived of the funds needed to continue providing decent service – and most even believed they would keep expanding. … In the US, by contrast, systems have been preparing doomsday scenarios, and advocates fear for the future.

We are seeing this with our own clients outside North America: Even with demand cratering, authorities continue to fund good service.

There’s one technical reason for this in some cases. In most wealthy countries outside North America, transit agencies are not free-standing local governments dependent on their own funding streams. Instead, any needed subsidy flows to public transit directly from the central government budget.[1] This means that public transit funding is debated alongside other expenses in a central budget, so the service level depends on what the nation or state/province values as a society, rather than what a transit agency can afford.

But there’s no question that apathy about public transit, and in some cases hostility, is higher in the US. In my work I hear three kinds of negativity:

- Cultural hostility to cities, which implies indifference to meeting their needs.

- Disinterest in funding things that are useful to lower-income or disadvantaged groups, or groups that are culturally “other” in some way.

- Especially aggressive marketing of new technologies as replacements of most public transit. (Many new technologies are compatible with high-ridership public transit, but some are not, and many are overpromoted in ways that encourage opposition to transit funding.)

All three of these are understandably worse in the United States than in most other wealthy countries.

In any case, if you’re in the US, remember: there is no objective reality behind the idea that Covid-19 is a reason to care less about transit. It’s just a US thing, and we could choose to make it different.

[1] By central government I mean whichever level of government is sovereign: In most countries this is the national government, but in loose confederations like Canada and Australia, it’s the state or province.

Why Are US Rail Projects So Expensive?

We’ve known for a long time that the US pays more than most other wealthy countries to build rapid transit lines, and especially for tunneling. If the incoming Biden administration wants to invest more in transit construction, then it’s time to get a handle on this.

We’ve known for a long time that the US pays more than most other wealthy countries to build rapid transit lines, and especially for tunneling. If the incoming Biden administration wants to invest more in transit construction, then it’s time to get a handle on this.

The transit researcher Alon Levy has been working on this issue for many years, has generated a helpful trove of articles is here. Alon’s work triggered a New York Times exposé in 2017, focus on the extreme costs (over $1 billion/mile) of recent subway construction there.

But while the New York situation is the most extreme, rapid transit construction costs are persistently higher than in comparable countries in Europe, where they are tunneling through equally complex urban environments.

Now, Eno Foundation has dug into this, building a database of case studies to help define the problem. Their top level findings:

- Yes, US appears to spend more to build rail transit lines than comparable overseas peers.

- This difference is mostly about the cost of tunneling, not surface lines. The US pays far more to tunnel 1 km than Europeans do, even in cities like Rome where archaeology is a major issue.

- Needless to say, the type of rail doesn’t matter much. Once you leave the surface, either onto viaducts or into tunnels, any cost difference between light rail and heavy rail is swamped by the cost of those structures. (This is true of bus viaducts and tunnels too, of course)

- Remarkably, stations don’t seem to explain the difference in rail construction costs. European subways with stations closer together still come out cheaper than US subways with fewer stations.

Most of us have known this for a long time — though I admit to being surprised by the last point. But it’s good to see a respected institute like Eno building out a database to make the facts unavoidable. If you want more rail transit in the US, it simply has to be cheaper.

Holiday Card, with Controversial Hummingbird

The card was lightly controversial because it has no public transit or urbanism theme, but I’m sorry: Hummingbirds are amazing. If you’ve never watched one in action I suggest that as a New Years Resolution. And when you get a green hummingbird at a red feeder, that basically ticks all the holiday boxes.

We are deeply grateful to all the clients and friends who’ve helped us get through this difficult year. We hope we’ve been helpful to you as well. Happy holidays, with best wishes and all necessary fortitude for 2021.

It’s OK to be Absolutely Furious

Today I took a stab at writing a holiday letter and discovered that, right at this moment, I can’t figure out how to cheer up transit advocates, or people who work in local government, or anyone else who loves cities. Since consultants like me are expected to exude at least some degree of optimism, this is more of a problem for me than it is for the average person.

Why? At the Federal level in the US, powerful forces, especially in the Senate, are happy to watch local governments implode in budgetary crisis, weakening the only level of government that citizens can influence. Particular hostility seems to be directed at transit agencies associated with big cities. In an absurdity that only Federal policy could create, high ridership in the big agencies before the Covid disaster is exactly why they are in such trouble now. New York, Washington, Boston and possibly others are looking at service cuts that will simply devastate those cities, undermining essential workers and destroying the access to opportunity without which an equitable economic recovery is impossible. Smaller agencies are in better shape at the moment, but if there isn’t a new funding package soon we’ll see devastating cuts across the US.

Tomorrow or next week, I will express optimism again and encourage constructive action. But I know that the journey to any authentic optimism goes through the anger rather than around it. So today I feel the need to state, for the record, that I’m absolutely furious: about what’s happening to transit in the US, and about many larger things of which that’s just an example.

Again, working consultants like me aren’t supposed to say this in public, and if I were at an earlier stage of my career I wouldn’t dare.

Please remember that when you deal with public servants or consultants at this time, and they don’t seem to be reacting in the way you think they should, that they are probably furious too, but are in roles where they can’t express that. In addition to being furious about all the things that you’re furious about, they have also been through a period of unprecedented assault on their professions. Because they did the long, hard work of learning about a topic so that they can help people deal with it, most have been slandered and a few have been threatened physically. So when you see these people managing their own emotions to keep working constructively, consider expressing some gratitude and admiration for that.

When I am in a room with some citizens trying to solve a problem together, we can’t get much done if everyone is just expressing anger in every moment. But even if we park it at the door in order to do our work, we shouldn’t deny it. In almost every meeting, I wish I could say: “I know how furious you are about all the injustice and cruelty and oppression and destructive behavior that surrounds us, in addition to your fears for yourself, your family, and your community. I’m angry too.” Maybe it’s my work to figure out how to say that, even to diverse audiences who may be angry about different things.

There will be many places where it’s not safe to talk this way. But I know I speak for many calm-seeming professionals when I say: I’m absolutely furious, and I hope you are too.

A Brief Detour into Comedy

Well, this isn’t your average interview.

“Nobody Listens to Paula Poundstone” is a comedy podcast series spun off by the US National Public Radio game show Wait Wait Don’t Tell Me. A while back they called out of the blue. Apparently they had done an interview with a parking garage designer, and a listener replied by asking them why they don’t interview the Human Transit guy, for balance I guess. I had all the leeriness of comedy that you might expect, but it came off better than I expected, and it was fun.

The podcast is here. After half an hour of comic banter between the hosts, the segment starts at 31:53 to 1:02:00.

Portland: A 30-Year Old Kludge Finally Fixed

Living in Portland, I still care about the details of transit network planning here, and here’s a thing that Portland folks should comment about, especially those who deal with downtown.

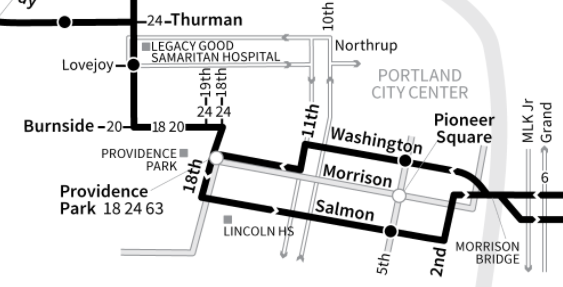

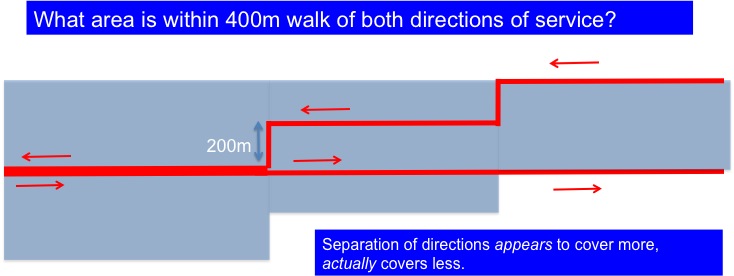

Back in the 1980s, when the current frequent grid network was laid out, there was a controversy about the east-west path that Morrison Bridge buses (now Line 15) should use across downtown. As a result of this, the two directions of service ended up five blocks apart, with westbound buses on Washington St and eastbound buses on Salmon St.

Separating the two directions of service, beyond the minimum required by typical one-way couplets, is a Very Bad Thing, because a service is useful only if you can walk easily to both directions of it.

Blue shows the area with easy access to service. As the directions of service get further apart, the area served gets smaller.

Why was this five-block split ever created? I was hanging around TriMet as a teenager then, so I think I remember. Nobody who designed this liked it. It was a political compromise, partly involving the department store whose large and busy loading dock fronted onto Alder, creating conflicts with buses.

The department store is long gone, but for some reason this was never fixed. I started banging this drum again about a year ago, and the objection I heard was that Alder has too much rush hour traffic, backed up from the bridge. While this is true:

- A problem that happens briefly, like rush hour congestion, shouldn’t define the route that buses use all the time.

- Congestion always happens where people want to go. Designing bus routes to avoid congestion usually implies avoiding logical paths that would be useful to the most people.

- Whatever time may be lost in that backup is far less than the time spent driving ten additional blocks, in the eastbound direction, to go down to Salmon St and back.

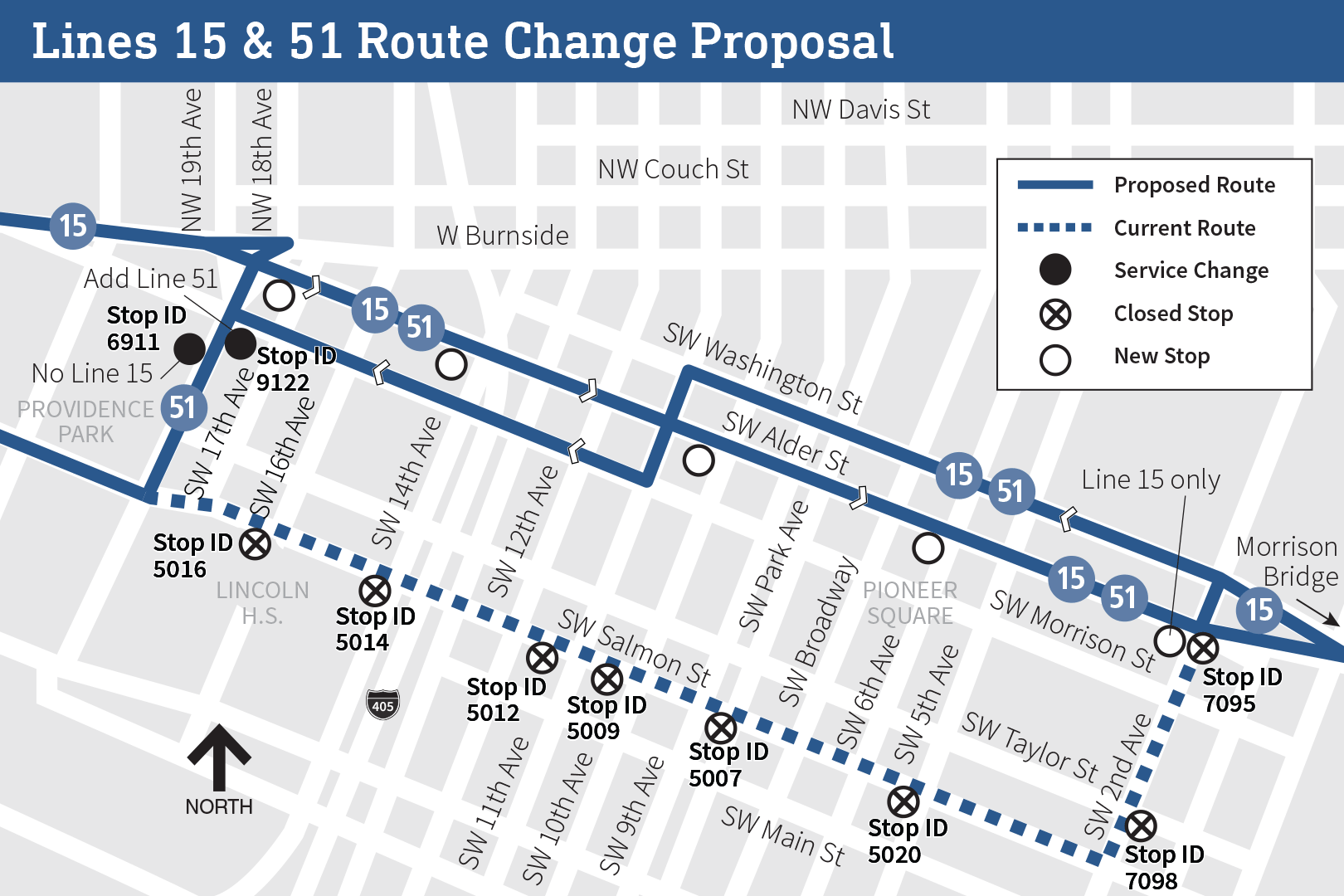

Now, TriMet is finally proposing to fix it:

Now, like any existing routing, some people find the Salmon St routing useful, probably including many municipal and county employees whose main offices are near there. But these people are already walking from distant Washington St to travel in the other direction anyway, so they’re proving that they can.

If you live in Portland, please comment on this! Tri-Met is taking feedback here. As always, you must comment if you like an idea, not just if you hate it. Negative comment predominates on almost all service changes, because people who like a change take it for granted that it’s happening anyway. Don’t be part of that problem! Comment here. There’s other cool stuff to comment on there too!

Livability and Protest in Portland: An Interview with Me

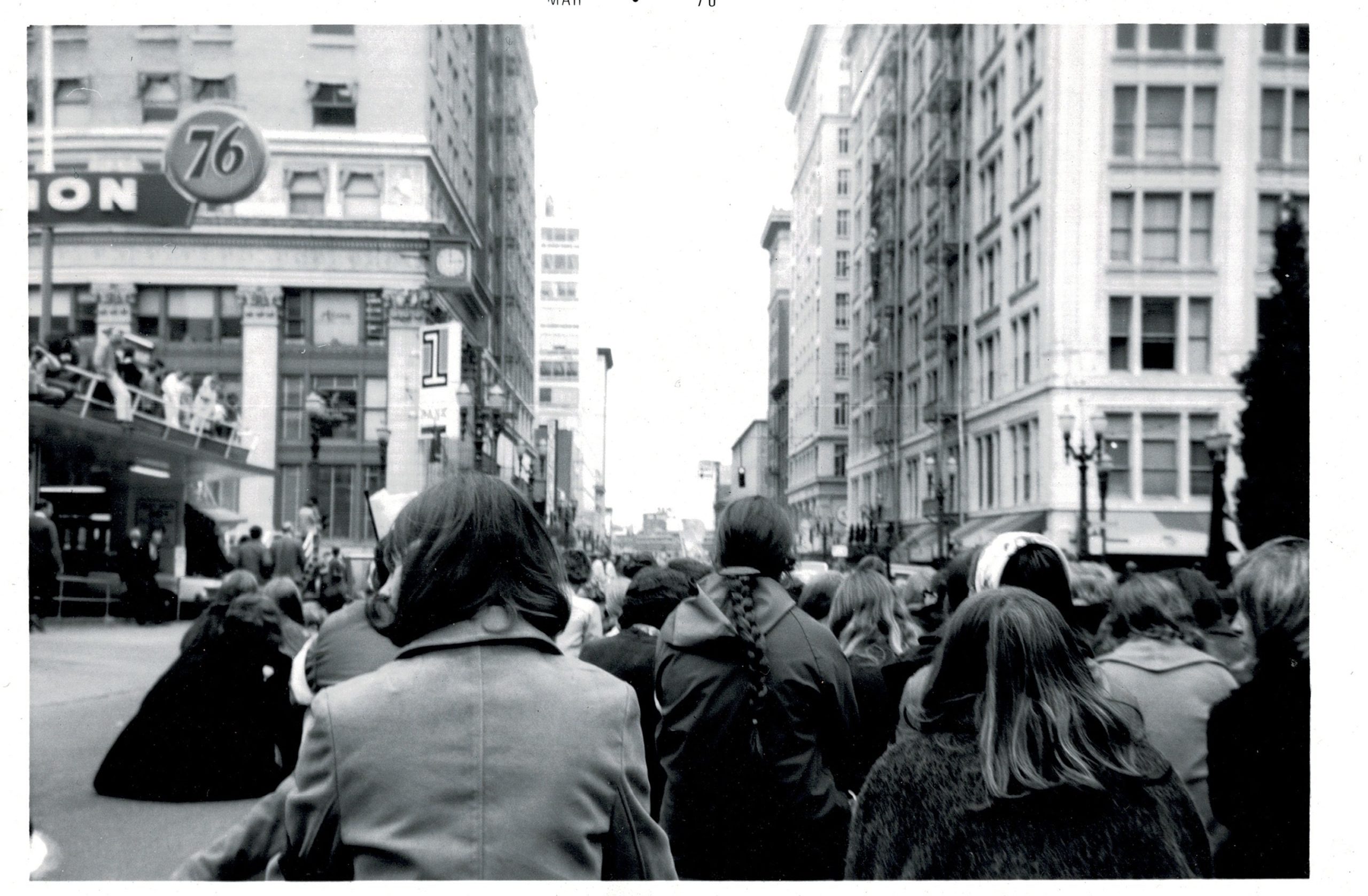

Protest against the Vietnam war in March 1970. Bonus points for knowing not just where this photo was taken, but also what the giant neon sign at the end of this street said.

Oregon Public Broadcasting has posted an interview with me about how Portland’s reputation for livability is related to its reputation for protest. OPB’s Geoff Norcross is a great interviewer, and it was a fun conversation. The audio and transcription are here.

“Through our livability, through the way we’ve built the city, we’ve created the stage on which those protests can express themselves effectively, but also attracted the kinds of people who are inclined to protest, who already see themselves to be as rejected by the system and want to stand up to it.”