Should proposed public transit infrastructure in the US be judged on whether it helps people go places so that they can do things? The US Federal Transit Administration (FTA) is asking this question right now.

FTA helps fund most major transit construct ion projects in the US. Recently, these programs have doled out about $2.3 billion per year in capital funding for transit projects across the country. The Senate Infrastructure Bill would nearly double the annual funding for these programs for the next five years. If there’s a piece of transit infrastructure you want to see, or one that you oppose, you should care about how the FTA makes its funding decisions.

ion projects in the US. Recently, these programs have doled out about $2.3 billion per year in capital funding for transit projects across the country. The Senate Infrastructure Bill would nearly double the annual funding for these programs for the next five years. If there’s a piece of transit infrastructure you want to see, or one that you oppose, you should care about how the FTA makes its funding decisions.

Congress has defined the criteria that FTA must use to evaluate the projects. But the FTA has broad discretion in deciding how to define the measures for each criterion. So now they are asking you, me, and everyone about how we ought to change or update those measures.

Their questions should make us optimistic about what US transit funding could become. They don’t sound like an ancient bureaucracy going through the motions of public consultation. Instead, the agency really seems to want our opinion about how they should measure the success of their investments, a decision that will directly determine what gets funded and built. Read the questions yourself if you don’t believe me.

Does it matter if we can go places, so that we can do things?

FTA asks many good questions, but one especially stands out.

Should FTA consider ‘‘access to opportunity’’ under the Land Use criterion? If so, how specifically could FTA measure it? For example, should access provided by the project to education facilities, health care facilities, or food stores be considered? Please identify measures/data sources that would be readily available nationwide without requiring an undue burden on project sponsors to gather and FTA to verify the information.

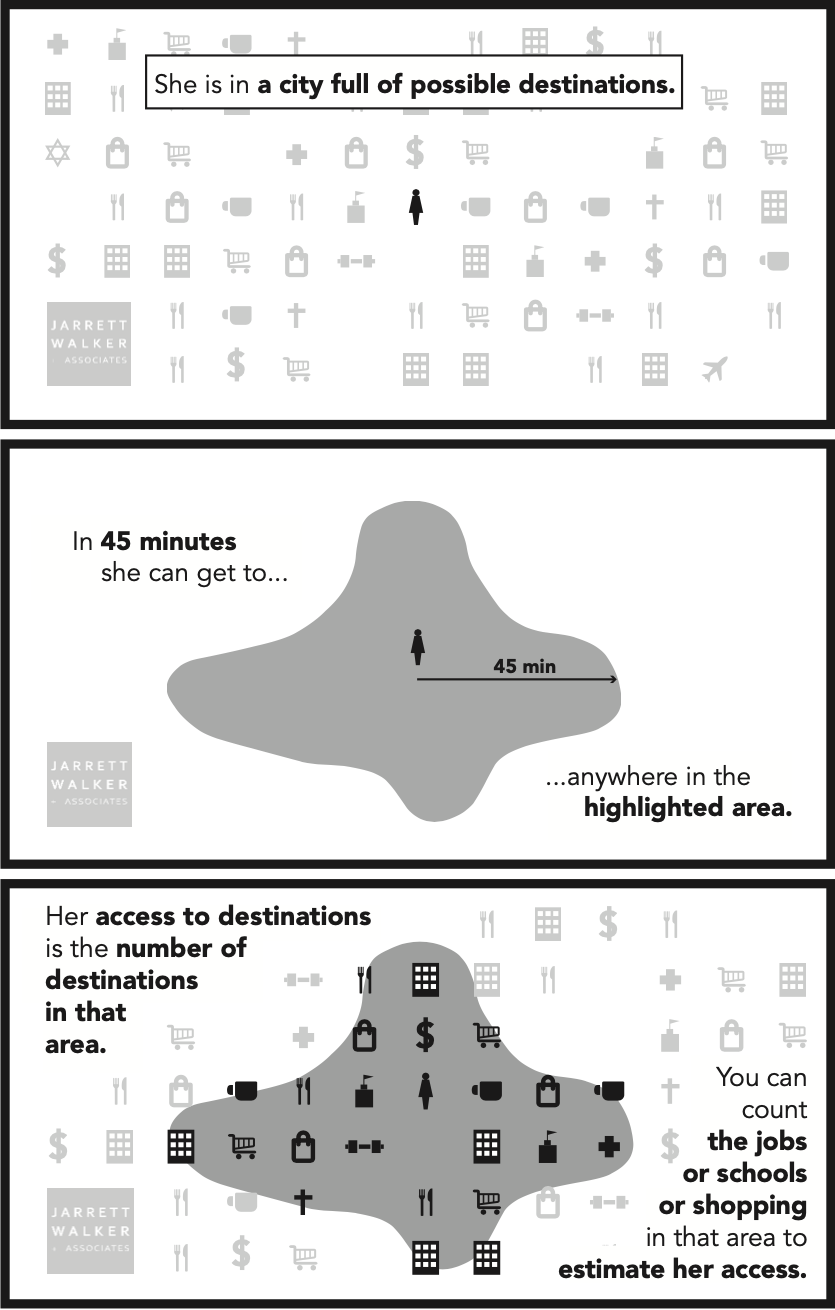

Access is your ability to go places so that you can do things in a reasonable amount of time. Access reframes discussions of travel time: Instead of asking how long it takes to go to a particular place, you look at how many useful places you can go in a given time. In short, we’re talking about access to opportunity, which means not just work or school but your freedom to do anything that requires leaving home.

If you’re not familiar with the concept, please see my full explainer here. But the most important point is that when we increase people’s ability to reach destinations in a shorter amount of time, we are improving ridership potential, revenue potential, climate emission benefits, congestion mitigation benefits, overall access to opportunity, and personal freedom, and we can also measure whether we’re doing these things equitably. Access measurement can help meet all of these seemingly disparate goals.

Access and the Land Use Criterion

When the FTA asks about whether access matters, they are thinking about this in the context of their Land Use criterion. They deserve an answer on this, although they also should hear about how caring about access would affect other criteria they care about, which I’ll touch on further below.

FTA’s Land Use criterion measures how much population and employment is around the stops or stations of a proposed project. The point is to determine that there is enough demand adjacent to proposed facilities. (The criterion is not about the ability to generate future development – that’s under a different criterion, Economic Development.)

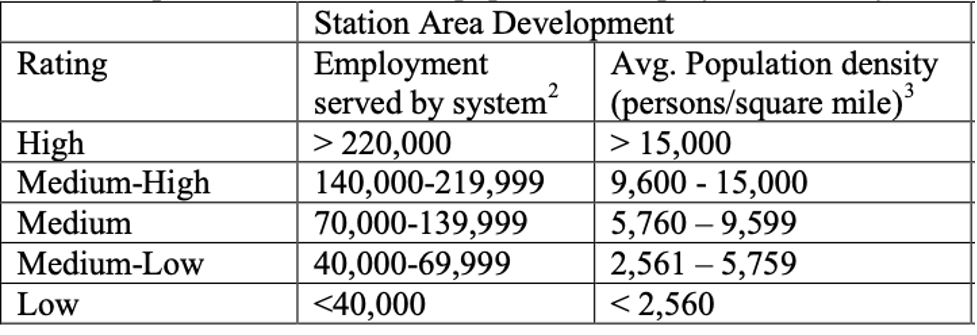

This table, from the FAST Updated Interim Policy Guidance dated June 2016, gives you a sense of how this evaulation works now:

Federal Transit Administration, Final Interim Policy Guidance Federal Transit Administration Capital Investment Grant Program, June 2016. p 15.

A project gets a higher rating if there’s more density around the station, and also if there’s more employment anywhere on the “system”.

But what do they mean by “the system”? Here’s the crucial footnote:

The total employment served includes employment along the entire line on which a no-transfer ride from the proposed project’s stations can be reached.

So all destinations that require a connection are excluded, while all destinations on the same line, even if they are an hour away, are included. In other words, as long as you get to stay in your seat, it doesn’t matter how much of your life you spend commuting. By contrast, if you can get to lots of jobs quickly with a fast transfer, those jobs don’t count in assessing the value of the line. Travel time, and hence access, don’t matter at all!

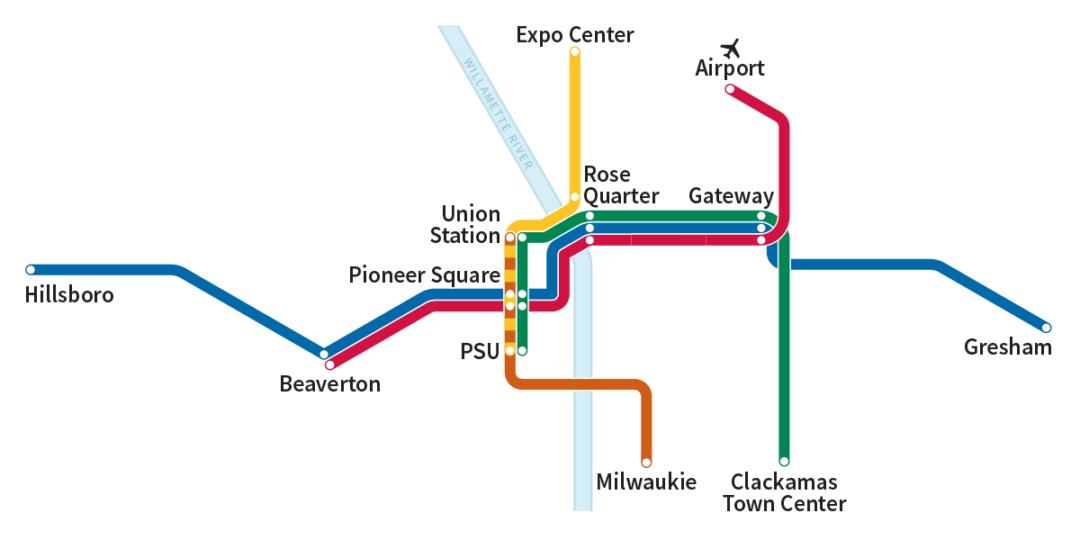

If you have an hour and 40 minutes to spare, you can go from Gresham to Hillsboro without leaving your seat! But should that count as access? Source: Trimet, Portland, OR.

For example, in Portland, where I live, a single light rail line will take you across the region, from Gresham to Hillsboro, in one hour and 40 minutes – far too long for a one-way commute. But under the current method, all the jobs in Hillsboro would be counted as providing value to someone in Gresham, while the jobs that are less than an hour away – on a trip that requires the train and a bus – count for nothing.

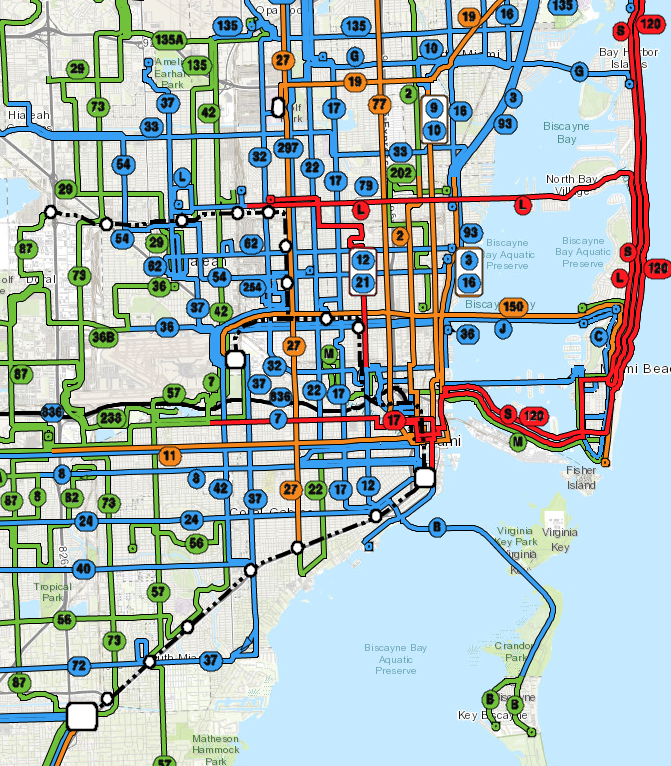

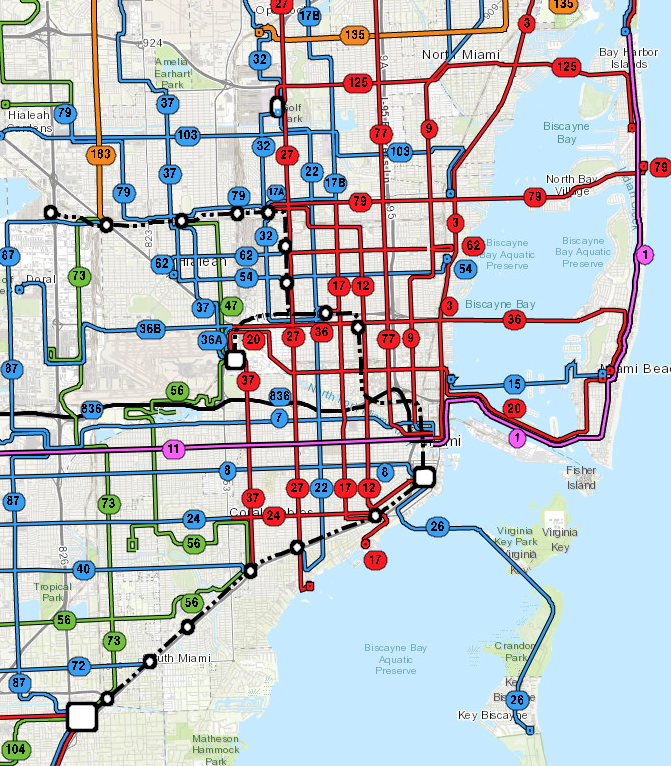

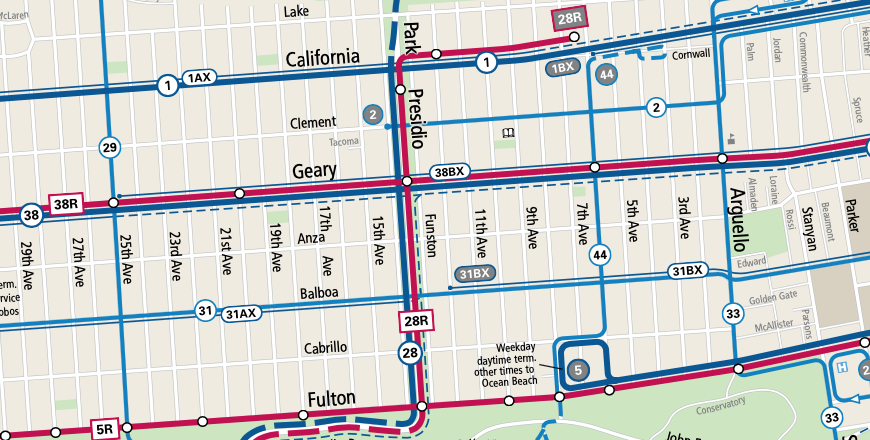

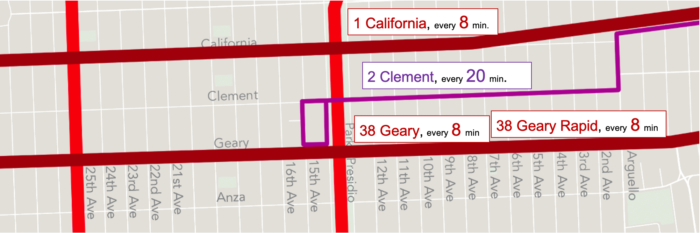

So “Employment served by the system” is really just “Employment served by the line” Likewise, the measure gives zero value to populations that are not at stations but that can get to stations easily via connecting buses. In short, the measure excludes all the benefits of actual networks, which are a bunch of lines working together to expand where people could go.

How would an access metric change this approach? Suppose the measure were something like “increase in the number of resident-job pairs that are connected by a travel time of 30 or 45 minutes.”

A resident-job pair is an imagined link between every resident and every job (or school enrollment). Each link represents a possible commute, which is an opportunity that someone might value, now or in the future. The number of resident-job pairs in a region is the number of residents times the number of jobs (or school enrollments). A very big number, but we have computers!

If we measured access in this way, what effect would it have on how FTA evaluate projects?

- It would still quantify the benefit of land use intensification around stations. These areas tend to get the largest access improvement from a project, so that improvement, multiplied by the density of population and jobs, would generate a higher score.

- It would measure what that density achieves for mobility. From a transportation perspective, the value of density around a line is that it provides the line’s benefits to more people, so that more people can get to more useful places sooner. So maybe we should measure what we’re really talking about.

- It would consider land use in the whole area that benefits from the project, not just around stations. It would reward communities that have thought about the total transit network more deeply and made some commitments about it. The tendency to propose a line in isolation, without thinking about its role in a network, is a very common problem in US transit infrastructure.

- It would refer to something that everyone cares about: their ability to go places so that they can do things.

What about equity? The current criteria specifically measure the quantity of affordable housing near stations, and its likely permanence – an important tool to discourage displacement due to gentrification. That measure definitely still matters.

But in addition, you could measure the access experienced by various racial or income groups, and make sure that this isn’t much worse what the entire population experiences. For low-income people, you could look at their links to low-wage jobs and educational opportunities, so that it emphasize the commutes that they are most likely to need or want. This would ensure that every element of the land use pattern is equitable in its most important aspect: the way that it ensures fast access to many opportunities.

Finally, FTA specifically asks whether access to “education facilities, health care facilities, or food stores be considered”. The answer is surely yes, because most transit trips are not work trips. We must measure access to all these things for populations likely to care about them, to the extent that the data permits.

For example, you could construct a database of all resident-grocery store pairs and run the same calculation, probably using a shorter travel time budget like 15 or 30 minutes. You could do the same for healthcare. You could construct a database linking school-age residents to school enrolments, and young adults to university and college enrolments. Retired people could be excluded from the residents-jobs database but included in databases of, say, links from residents to healthcare, food, etc. There are many ways to broaden the diversity of travel desires that a good network needs to serve.

The relative importance or weighting of all these measures would need more debating, possibly based on the size of each market in the region’s travel patterns with some bonus weighting for equity.

But to sum up: When we talk about existing land use as a transportation criterion, what do we really mean? I think we mean that the land use pattern contributes to a transit project’s ability to expand many people’s ability to get to many places in a reasonable amount of time. So let’s measure that!

Access or Prediction? A Broader Question for FTA

Land use is just one of the six criteria that FTA uses, and the one they have specifically asked about. The others are:

- Mobility Improvement

- Cost Effectiveness

- Environmental Benefits

- Congestion Relief

- Economic Development

Except for Economic Development, all of these are built on the same shaky foundation: a prediction of ridership well into the future. Access analysis may help to shore up those foundations, because an access calculation is much more certain than a prediction.

That should be especially obvious during the Covid-19 pandemic. The utterly unpredicted ridership trends of 2020 are just an extreme example of the kind of unpredictability that we must learn to accept as normal. As I argued in the Journal of Public Transportation, we can’t possibly know with certainty what urban transportation will be like in 10-20 years, or how our cities will function, or what goals and values will animate people’s lives.

Still, ridership prediction models generally begin with something like an assessment of access. If a project improves travel time for a lot of possible trips, that’s the starting point for a high ridership prediction. But then, predictive modeling mixes in a bunch of emotional factors that amount to assuming that how humans have behaved in the recent past tells us how they will behave in the future. This is equivalent to telling your children that “when you’re my age, I know you’ll behave exactly the way I do.”

Of course some human behavior is predictable. We’ll still need to eat. But the world is changing in non-linear ways, which means that the recent past is becoming less reliable as a guide to the future. So if we measured access, we’d still be measuring ridership potential, but without all the uncertainty that comes from extrapolating about human behavior, or telling people that you know how they’ll behave 20 years from now.

Here’s how the access concept could illuminate each of the FTA’s criteria:

For the Cost Effectiveness criterion, Congress has required that FTA measure the capital and operating cost of a project and divide that by the total number of trips (predicted by a model) to effectively measure the cost per trip. Since it would take an act of Congress to change this measure, it stands to reason that FTA should be looking to access measures as factors to use for other criteria. However, we should also assess projects based on the increased access provided per dollar expended.

For the Congestion Relief criterion, FTA measures the number of new riders on the project, yet again based on ridership prediction. We know that transit expansion by itself doesn’t solve congestion, just as road expansion doesn’t either. But transit expansion can do very important things much better than road expansion: it can allow for drastically more economic growth and development at a fixed congestion level and improve the ability of those who cannot drive to participate in the life of the community. It does this by expanding the access to opportunity that’s possible without generating a car trip. So, there’s a good role here for access measures as an indirect way to tell us whether a transit project has a high likelihood of providing an option to avoid congestion.

For the Environmental Benefits criterion FTA looks at changes in predicted air pollution, greenhouse gases, energy use, and safety benefits. Most of these factors are calculated based on predicted ridership. So, FTA is building many measures on the questionable assumption that ridership is predictable. Again, we know that greater access tends to mean greater ridership, which means great environmental benefits. Perhaps we need more research to be able to quantitatively tie improvements in job access to environmental benefits. If FTA sticks with its current measures for environmental benefits, it makes the case for using access measures in other criteria even stronger, if nothing else than to provide a wider range of measures that aren’t tied to one modeling outcome.

For its Economic Development criterion, FTA evaluates how likely a project would induce new, transit supportive development in the future by looking at local land use policies. How might access be a useful measure here? It depends a lot on what kinds of real estate investors we have in mind. The real estate business already calculates car access for practically every site they consider. They should be encouraged to care about transit access (and they sometimes do).

To Sum Up

All of the FTA’s criteria are attempting to answer the question “Which of these potential transit projects across the US is the best investment and therefore worth of funding?” That begs the question of what we, citizens of the US, think we value about our investments in transit. Access starts with one insight about what everybody wants, even if they don’t use the same words to describe it. People want to be free. They want more choices of all kinds so that they can choose what’s best for themselves. Access measures how we deliver those options so that everybody is more free to do whatever they want, and be whoever they are.

Should we be investing in projects that score well on predictions of what we think people will do in the future? Or should we be investing in projects that we can geometrically prove will drastically increase the average person’s access to opportunity?

Whatever your view on these topics, now is the time to respond to the FTA’s questions!

When I started my transit planning career in the early 1990s, we faced this kind of suburban street but the stakes were usually lower, because transit wasn’t carrying huge volumes of people to these places. Most of the ridership in major metro areas was in the relatively walkable pre-war inner city. But all that’s changed for the worse. Today, in many US transit agencies I study,some of the highest ridership bus services are on these suburban arterials. People who need transit are forced to live and work in these places, so they have no choice but to dash across those nine lanes, if they are fit enough to dash. My father, in his 70s, used to have to cross a street like this one to catch the bus. He couldn’t dash. He could only hope.

When I started my transit planning career in the early 1990s, we faced this kind of suburban street but the stakes were usually lower, because transit wasn’t carrying huge volumes of people to these places. Most of the ridership in major metro areas was in the relatively walkable pre-war inner city. But all that’s changed for the worse. Today, in many US transit agencies I study,some of the highest ridership bus services are on these suburban arterials. People who need transit are forced to live and work in these places, so they have no choice but to dash across those nine lanes, if they are fit enough to dash. My father, in his 70s, used to have to cross a street like this one to catch the bus. He couldn’t dash. He could only hope.