When respected authorities speculate about why transit ridership is falling in the US, they usually cite a 2015 paper by the (respected) Mineta Transportation Institute, authored by Bhuiyan Alam, Hilary Nixon, and Qiong Zhang.

The paper has one blindingly obvious conclusion that we shouldn’t need statistics to prove: If you want ridership, you have to run service. The quantity of service, measured several ways, overwhelmingly determines ridership outcomes. My comments about the paper in no way question this conclusion.

Still, the paper has problems that are common in papers in the statistical social sciences. To some extent, I’m not even critiquing the paper so much as the discourse from which it arises.

(And if this is tl;dr, by the way, there’s a “Conclusion” section you can scroll down to.)

Useful Findings, Misleading Interpretation

The study seeks to explain the variation in passenger boardings per capita, an imperfect but easily calculated measure of ridership. It looks at a large set of things that could explain this variation and concludes that:

The results indicate that gas price, transit fare, transit supply, revenue hours, average headway, safety, transit coverage, and service intensity show statistically significant impacts on transit demand by bus.

All of these except gas price are internal. In simple language, an internal variable is a thing that someone could change, while an external one (like the weather) is one that they can’t. [1]

But their interpretation of this is deeply misleading:

The results show that the internal variables, the factors that transit managers and operators control, are predominantly the significant predictors of transit travel demand by bus mode. Seven out of eight internal variables in the OLS regression model proved to be significant factors in determining travel demand by bus. [emphasis added]

It is utterly false to say that the internal variables are under the control of “transit managers and operators,” unless you think they can print money. Again, these variables are “transit fare, transit supply, revenue hours, average headway, safety, transit coverage, and service intensity.”

Transit managements can turn fares up or down, and they can be more or less careful about safety, and they can hire firms like mine to help them redesign their networks. But the larger reality of service quantity — the most important point of the entire paper — is mostly the result of investment decisions made above their level. Transit is mostly subsidized due to its public benefits, and the level of that subsidy is controlled by some mix of elected officials and voters. Management has a marginal role in how efficiently that subsidy is translated into service quantity. [2] Mostly, you get in service what you’ve paid for in subsidy.

This mistake goes to a critical problem in the way the bus ridership decline is being discussed, and why so much activism around the issue is misfiring. More people are yelling at their transit agencies than are yelling at the elected officials who actually control service quantity The Mineta paper’s careless language encourages that confusion. There is no point in telling transit managers that they should run more service. They agree with you. You need to tell elected officials this.

What Doesn’t Matter?

The findings about what matter to transit ridership are interesting, but so are claims about what factors don’t matter. Here the authors make sweeping claims about how clueless we transit planners are:

The study found that certain variables that many transit planners view as important determinants of transit demand did not have significant impacts on transit demand. … Variables such as transit orientation pattern, median household income, percentage of college population, percentage of immigrant population, vehicles per household, and MSAs in the South … do not impart significant effects on transit demand by bus. … Population density and the percentage of households without cars show insignificant impacts on transit demand …

To which I can only say, it depends on how you measure these things.

The finding that population density doesn’t matter is based on a common mistake. The authors measure the total density of Metropolitan Statistical Areas, which are aggregations of US counties that may contain vast expanses of rural area and even wilderness. (More on this, with photos, here.) But even average density of the truly urban area is not what matters. What matters is density adjacent to transit service. (The late Paul Mees made the same mistake in his book Transport for Suburbia, as I discuss here.)

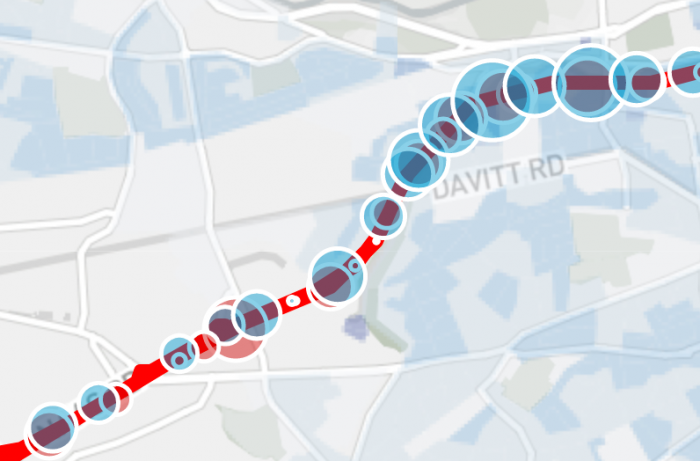

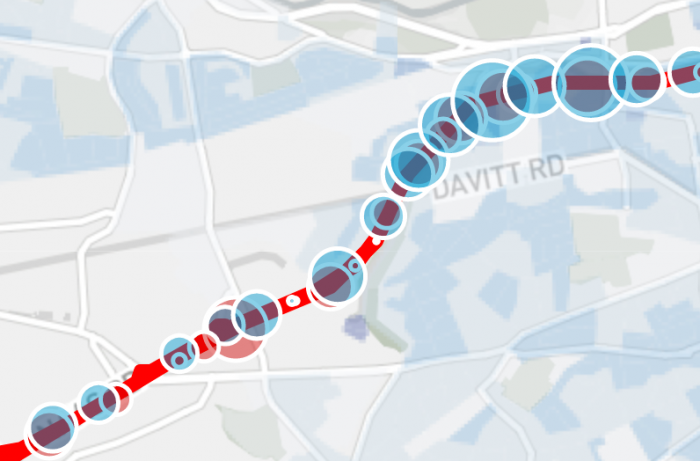

This is an example of a case where some geometric thinking would have helped, which is what I tried to do in my transit ridership explainer. The residential density that matters to transit is the number of people within a fixed radius of a transit stop. If ridership wasn’t twice as high where density is twice as high, this would mean that individuals living at low density are more likely to use transit than those living at high density. Such a claim would not only be wildly counterintuitive, it’s also disproven by virtually every transit agency’s stop-by-stop ridership data, as long as you focus narrowly on density near transit.

A segment of Dublin’s bus route 13, with passenger boardings as dots and residential density in the background. More density right around the route means more ridership. Makes sense, doesn’t it?

Problems with Rates

The confusion about how to measure density also affects a confusion about terms expressed in percentages, medians or averages, as most of the demographic variables are.

The authors run correlations with the percentage of people who are immigrants or college students. Vast parts of an urban area where transit isn’t abundant enough to be useful, if it exists at all, are counted in these rates. The median income of an entire city matters less to ridership than the median income of the parts of the city served by useful transit. These are always very different things.

That’s why our firm almost never studies or maps percentages; instead, we study densities. We draw maps of the density of poor people, or students, or seniors, or whatever. Because only that shows you how many people we’re really talking about, and where they are.

Conclusions

Too often, social science papers rely on correlations without thinking about what transit is spatially. Everything I’ve said here will be blindingly obvious to any practicing transit planner — not just because they show up in properly granular analyses but because the mathematical consequences of them not being true are so nonsensical. That’s why I’m confident in relying on geometric claims in my own work. They tend to win arguments in the political world because they don’t require anyone trust a black box of analysis that’s studded with assumptions, or to assume that experts always know best.

The biggest single mistake in this and most similar studies is the false confidence in aggregating data across a metro region. It is geometrically inevitable that any remotely viable transit agency will distribute its benefits very unequally across the land area of its region — especially in response to density — and the way that transit’s benefits are distributed over a city means that total inputs and outputs at the citywide scale don’t matter very much.

But these papers are at their most exasperating when their resistance to geometric thought is coupled with unfounded claims about how clueless we practitioners were before this paper enlightened us. As a PhD myself, I have the highest respect for the work of scholarship. But a regression analysis is only as good as the assumptions that went into it, and these need much firmer grounding in geometric reality, as well as in the reality of how transit decisions are actually made.

Nevertheless, the main point of the study, and the one for which it’s most often cited, is indisputable: Network design projects can help improve ridership for a given amount of money, but for step-changes in ridership, you have to fund more service.

[1] The internal/external distinction, routine in the social sciences, is entirely relative in ways that should be more clearly marked in papers. Whether a factor is internal or external depends on the selected point of view. My reaction to seeing transit quantity described as internal is that it is not in control of the stated point of view, namely “transit managers and operators.” Weather used to be the paradigmatic example of an external variable, but now that we know it’s partly the result of human actions, it could be internal if you take the long view of human agency.

[2] Not a zero role, but very small compared to the magnitude of cost involved.

In her spare time, Toronto Chief Planner Jennifer Keesmaat hosts a podcast series called

In her spare time, Toronto Chief Planner Jennifer Keesmaat hosts a podcast series called  Austin.

Austin.