I’m just home from a week in Montreal, one of Canada’s most complex and intriguing cities for urbanism and transit, thanks to the Quebec public transit association ATUQ. In addition to speaking at the ATUQ conference, I had breakfast with the nonfiction writer Taras Grescoe (author of Straphanger and the matching blog), gave a lecture at McGill for the access scholar Professor Ahmed El-Geneidy, did happy hour with the team at TransitApp, and had an interesting two hour meeting with executives of the Longueuil transit agency RTL, which serves the southern suburban area. The weather (everyone made sure to remind me) was unusually nice for late October, perfect for very long walks, and the trees of this tree-rich city were screaming for my attention.

Montreal is mostly a large expanse of more or less European density, almost all very walkable and with an extensive system of separated two-way bike lanes. Architecturally, it’s an engaging jumble, with some buildings seemingly imported intact from Haussmann’s Paris while many others are of elegant industrial brick.

Over it all looms the spectre of Brutalism, about which most locals have strong feelings. A major building spree in the 1960s left a vast legacy of this polarizing style. It’s often prominent on the skyline, as though installed by colonists to surveil the quaint old city.

About half of my time was spent in the newer suburbs of the south shore. I had a chance to experience two very dense recent developments, one around the Longueuil metro station which includes the University of Sherbrooke’s local campus …

… the other in Brossard, on the new REM driverless train line, an impressive Vancouver-scale knot of density, still partly under construction, that all dates from the last few years.

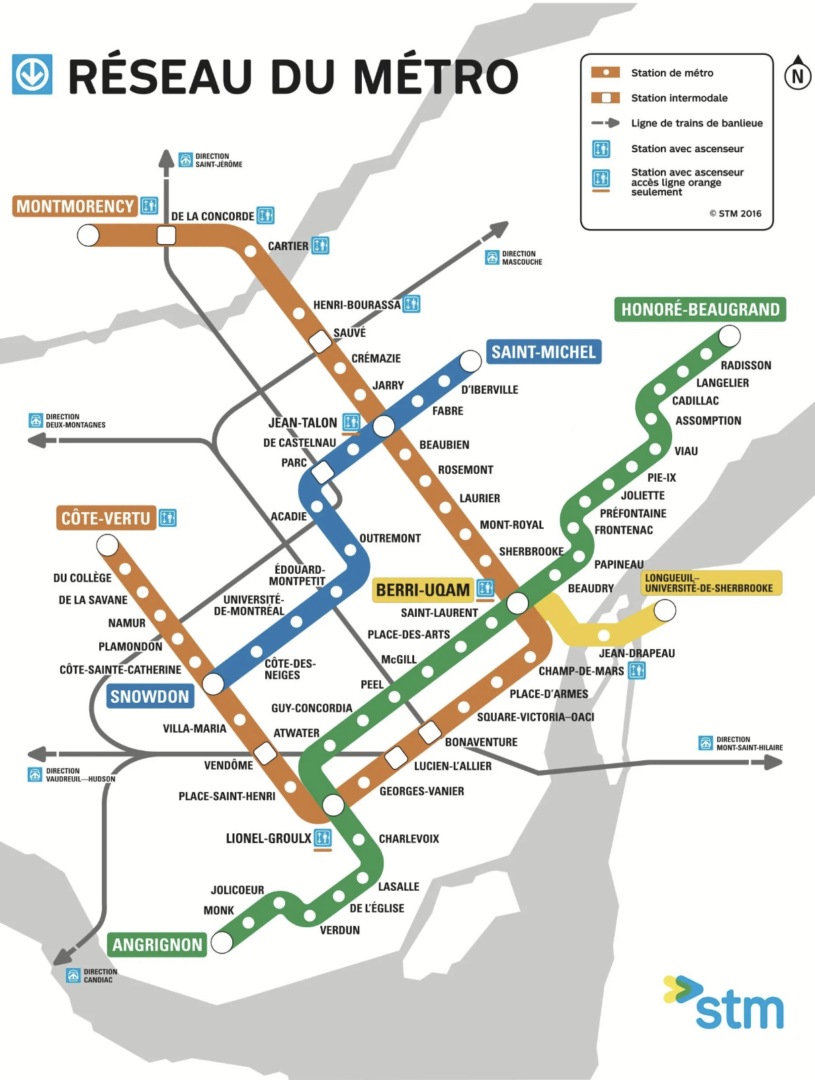

It is great to see such density around rapid transit but I noticed some odd things about the network. The famous metro, which dates from the 1960s, is not kind to Longueuil, serving it with a stubby three-station Yellow Line that requires one transfer to go almost anywhere, with quite a long walk at the key hub of Berri-UQAM.

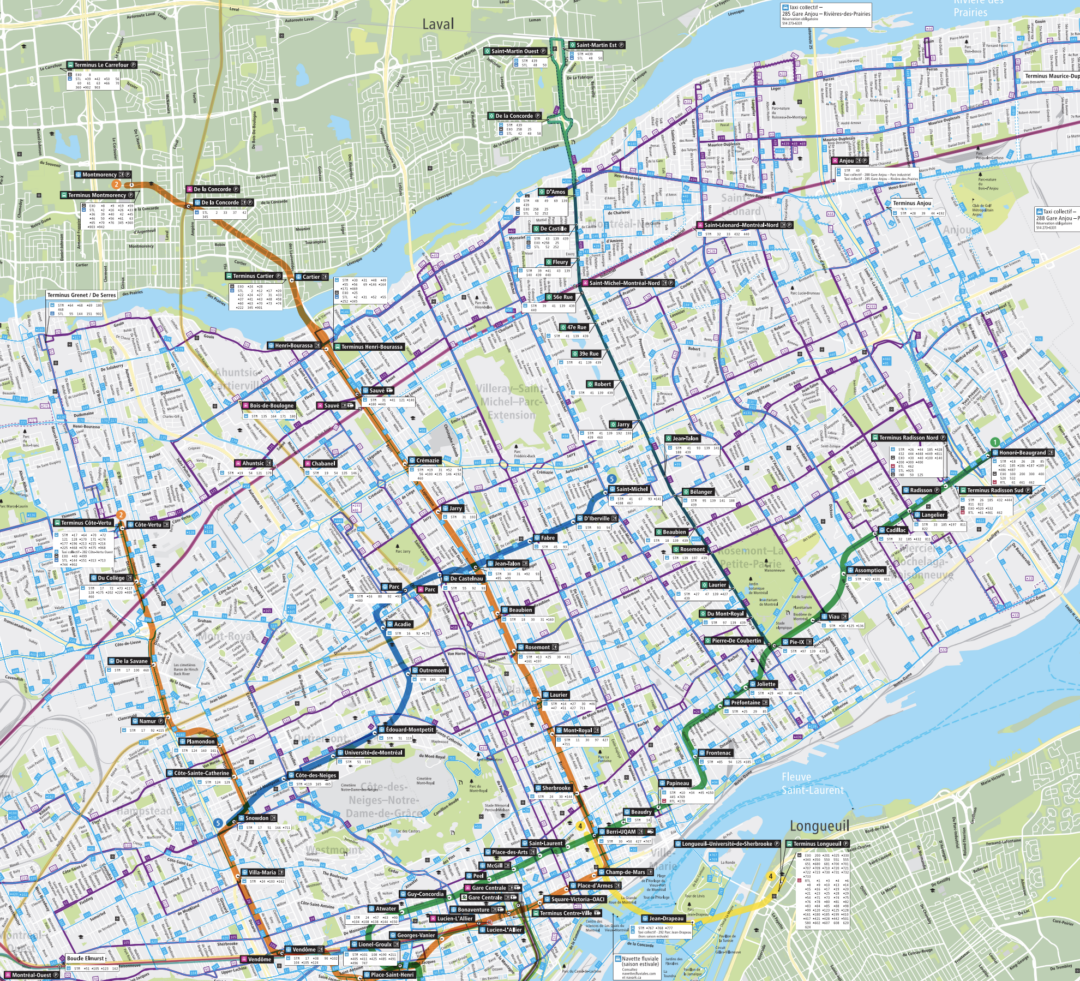

Apart from this, the structure of the metro is good for Montreal, a city of continuous high density in a mostly grid pattern, interrupted only by the royal mountain just north of downtown. This slice of the STM network map shows how frequent buses (purple) and one BRT line (the north-south dark green line) fill in gaps in the metro grid across some of the densest parts of the city. Unfortunately the city’s transit agency, STM, recently retreated from their “10 minute network” under budget pressure, but the purple lines are still, I assume, no worse than 15 minutes at most hours.

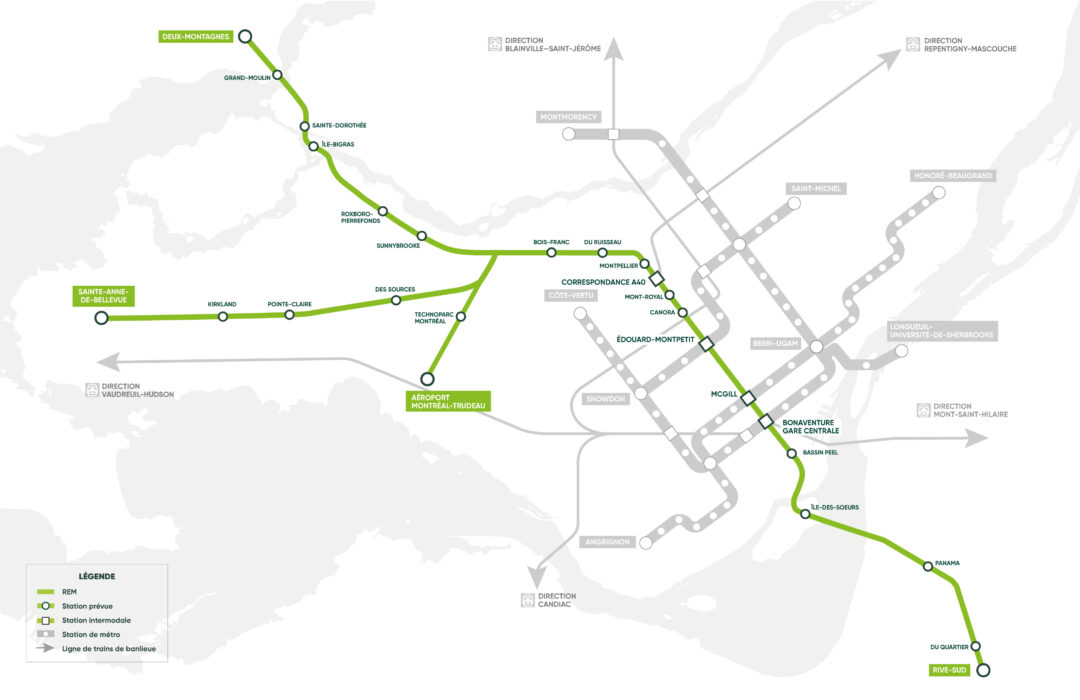

Many people bent my ear about the new driverless REM, which is currently just a short line from downtown Montreal south to Brossard but will soon expand into a large system with three lines reaching into northern and western suburbs, including one to the airport. (Click to enlarge and sharpen)

Planned REM network, with the existing Metro in wide grey lines and the infrequent commuter rail in narrow gray lines. The segment open now is from Bonaventure/Gare Centrale south to Brossard (marked “Rive Sud”). The segment between McGill and Édouard Monpetit is the existing tunnel under the mountain. McGill is downtown and Édouard Monpetit serves the University of Montreal. Source: REM https://rem.info/fr/actualites/la-vraie-facture-du-rem

And yes, I know some of you need pictures of trains, so here is REM sliding into the station behind the platform doors:

Here it is in the median of the freeway at Du Quartier station. Interesting that it’s overhead pantograph technology, not third rail.

Like the Canada Line in Vancouver, it was a project of a pension fund, which will make good money off of the resulting densification. But as such, it bypassed many of the usual planning processes in ways that I heard some grumbling about. It is also taking over the historic rail tunnel under the mountain between McGill and Édouard Monpetit stations, which is currently used by much less frequent commuter rail. That’s good news for getting more access benefit out of the old tunnel, though I heard some displeasure from people who had wanted to route a future Toronto-Montreal high speed rail link that way. The tunnel deserves frequent transit not just because it’s a link between downtown and the large University of Montreal, located just west of Édouard Monpetit station, but also because the result is a new north-south element all the way across the grid and extending into the suburbs north and south. The ultimate planned frequency is 10 minutes on each branch (including one to the airport) so about 3 minutes on the common segment.

Overall, I think the REM is a great contribution. The pension fund has learned from the notorious mistake on Vancouver’s Canada Line, which was to undersize the platforms to the point that that line is already out of capacity. REM is clearly built with room for growth.

I expect the REM’s Brossard segment to remain a tourist attraction, at least as far as Ile de Soeurs. As the train leaves the underground station at Bonaventure / Gare Centrale, it immediately makes a languorous S-curve over an industrial area, as though intentionally offering every passenger a photogenic view in all directions. (Train geeks will also enjoy looking down at the various passenger trains stored in the rail yards below.) It reminded me a bit of the gratuitous circuitousness of the Disneyland monorail. This long curve, sure to be costly in terms of travel time, is doubtless a concession to available right of way. But it certainly produced a great view of downtown — dramatically backlit in October by the bright red forested hills — and I hope many future generations will delight in the same vista.

The Montreal region certainly has its transit challenges. They have a Provincial funding source for transit operations (unusual in Canada) but the Province is trying to reduce it, demanding “optimizations” from the transit agencies. This term, of course, only makes sense if there is a shared notion of the goal of public transit, which in North America there usually isn’t. In my remarks at the ATUQ conference I focused on the tradeoff between ridership goals and coverage goals, because until you think about that, you won’t know what you should be “optimizing.”

The tangle of agencies raises all the usual challenges, and I heard some people express envy for Vancouver’s single-agency structure. There are three large local-serving transit agencies (one each for Montreal, Laval, and greater Longueuil) plus several smaller ones. There’s also a regional commuter rail service (Exo). Now REM is yet another organization in the mix.

The fare structure is challenging. There is a fare card, but it works in the Parisian manner, storing various tickets but not allowing a pure stored value, which is a hassle for visitors and occasional riders. No machine would put a one way ticket from Montreal to Longeuil on my smartcard, so I had to deal with a human ticket agent selling me pieces of paper. (I hadn’t dealt with a human ticket agent in French since my 1980s sojourn in Paris as a young man, so there was a slight frisson of nostalgia to this experience, but only slight.)

Over it all is the recently created ARTM, a new regionwide agency that is supposed to take over all the long-range planning, and through which Provincial funding for each agency will flow. I asked several informed people to describe ARTM’s role and its division of labor with the local agencies, and got several different answers. Obviously, such an interconnected region needs some kind of regional authority, but for now, some anxiety among the transit agencies is understandable as they figure out their roles. As I’ve argued before, there are many strengths to having multiple local-serving transit agencies in a big urban region as long as they are well integrated and coordinated. It will be interesting to see this new agency step into this role. We can expect Montreal to continue to be one of North America’s most interesting transit cities.