Taras Grescoe. Straphanger: Saving Our Cities and Ourselves from the Automobile. Macmillan, 2012.

When the publisher of Taras Grescoe’s Straphanger asked me to review the book, I felt the usual apprehension. Shelves are full of books that discuss transit from a journalist’s perspective. They often get crucial things wrong, as do many journalists’ articles on the topic. I wondered I was going to endure another four hours of watching readers being innocently misled on issues that matter.

Grescoe does a little of that, but he also shows why spectacular writing compensates for many problems of detail. Straphanger is a tour de force of compelling journalism and “travel writing” – friendly, entertaining, funny, pointed, and (almost always) compelling. Like any good explainer, he announces his prejudice at once:

I admit it: I ride the bus. What’s more, I frequently find myself on subways, streetcars, light rail, metros and high-speed trains. Though I have a driver’s license, I’ve never owned an automobile, and apart from the occasional car rental, I’ve reached my mid forties by relying on bicycles, my feet, and public transportation for my day-to-day travel … I am a straphanger, and I intend to remain one as long as my legs will carry me to the corner bus stop.

Grescoe and I have almost all of this in common, but I felt a pang of regret at this posture. To the mainstream, car-dependent people who most need this book’s message, Grescoe has just announced that he’s a space alien with three arms and a penchant for eating rocks. But there’s a positive side: once you decide you’re not in danger, eccentric tourguides can be fun. Perhaps I have a poor dataset from living in “officially weird” Portland, and before that in San Francisco, but in a culture that seems increasingly welcoming of eccentricity and difference, there may be an audience for Grescoe among the motoring set.

Because this is what Grescoe is at heart: A great tourguide, in this case a travel writer, showing you around some fascinating cities, exploring intriguing transit systems, and introducing us to vivid and engaging characters, all while having fun and sometimes dangerous adventures. These last are important; Grescoe has had enough traumatic and confronting experiences that he can describe straphanging as a form of endorphin-rich adventure analogous to mountain climbing or skydiving. I look forward to the movie.

Statistics are cited lightly but to great (and usually accurate) effect. Effective and quotable jabs are everywhere:

“The personal automobile has, dramatically and enduringly, broadened our horizons. In the process, however, it has completely paved them over.

Grescoe has a great eye for characters, too. Who can fail to be charmed, for example, by this portrait of a character I hadn’t known: Bogotà mayor Antanas Mockus, alter-ego of his successor, the aggressive and practical Enrique Peñalosa:

Working with a tiny budget and no support from district councillors, Mockus focused on … undermining cycles of violence through jester-like interventions in daily life. He dismissed the notoriously corrupt traffic police and hired four hundred mimes to shame drivers into stopping at crosswalks. … Taxis drivers were encouraged to become “Gentlemen of the Crosswalks,” and every new traffic fatality was marked with a black star prominently painted on the pavement. To discourage road rage and honking, he distributed World Cup-style penalty cards to pedestrians and motorists, a red thumb’s down to signify disapproval, a green thumbs up to express thanks for a kind act … Seeing tangible evidence of municipal progress, citizens once again began to pay their property taxes … and the once-bankrupt city’s finances began to recover.

What’s wrong with this book? Well, if it’s travel writing, nothing; travel writing is about the adventure, and while you learn things from it, you expect to learn subjective, unquantifiable things that may be inseparable from the character of your guide. Journalism, on the other hand, has to get its facts right, or at least state its biases. Grescoe gets a pass on his largest biases, mostly because he’s entirely aware of them and happy to point them out.

But there are a few mistakes. Like many commentators, Grescoe throws around meaningless or misleading data about urban densities. Here’s a typical slip:

Thanks largely to the RER, the metropolitan area of Paris, with over 10.2 million residents, takes up no more space on the Earth’s surface than Jacksonville, Florida, a freeway-formed city with fewer than 800,000 residents.

This doesn’t seem to check out, unless some subtle and uncited definition of metro area is being used. (Wikipedia tells me that the City of Jacksonville is 882 sq mi in area while the Paris with 10.3 million residents is 1098 sq mi.) But even if it did, this is the classic “city limits problem.” Jacksonville is a consolidated city-county whose “city limits” encompass vast rural area outside the city, whereas “metro Paris” is by definition a contiguous area that is entirely urbanized. An accurate comparison with metro Paris would look only at the built-up area of Jacksonville, which is tiny compared to Paris. The point is that any talk about metro areas or cities is prone to so many different definitions, including some really unhelpful ones, that it’s wrong to cite any urban density without footnoting to clarify exactly what you mean, and how it’s measured. Grescoe is far from alone in sliding into these quicksands.

As with many journalists, Grescoe’s sense of what would be a good transit network is strongly governed by his emotional response to transit vehicles and technologies. Grescoe is very enamored with rapid transit or “metro” service to the point that he sometimes misses how technologies work together for an optimal and liberating network.

He claims, for example, that there should be circular metro lines around Los Angeles, Chicago, and Toronto. In fact, circular or “orbital” services (regardless of technology) rely not just on network effects but also on being radial services into major secondary centers. This is why the Chicago Circle Line made no sense: Chicago is so massively single-centered that there are few major secondary centres sufficient to anchor a metro line until you get way out into the suburbs, at which point concentrations of jobs are laid out in such transit-unfriendly ways that no one line could serve them anyway. Chicago is going the right direction by improving the speed and usefulness of its urban grid pattern of service – a mathematically ideal network form that fits well with the shape of the city. Toronto has similar geography and issues. As for Los Angeles, this is a place with so many “centers” that the concepts of radial vs orbital service are meaningless. Especially here, where travel is going so many directions and downtown’s role is so small, the strong grid, not the circle, is the key to great transit.

Grescoe is clear enough about his strongest bias:

“I don’t like buses. … Actually, I hate them.”

Despite his opening statement that “I ride the bus,” Grescoe repeatedly associates buses with losers, and with unpleasant experiences. In correspondence with me, he wrote: “The anti-bus bias you perceive was a concession to North American readers whose experience of buses tends to be negative.” Again, this is understandable as travel writing, but it’s tricky as journalism and very tricky if the purpose is advocacy. When you presume a bias on the part of your reader, with the intent of later countering it, you can’t really control whether you’ve dislodged the bias or reinforced it. I felt the bias being reinforced; other readers may have different responses.

Again, the problem with anti-bus bias is not that I don’t share it. The problem is that if you set transit technologies in competition with one another, the effect is to undermine the notion that technologies should work together as part of a complete network. If you want a network that will give you access to all the riches of your city, buses are almost certain to be part of it – even if, as in inner Paris, you have the densest subway system in the world. Hating buses – if that becomes your primary focus — means hating complete networks.

When it comes to Bus Rapid Transit, Grescoe accepts the common North American assumption that the place to see BRT is Bogotà or Curitíba. So he comes back from Bogotà with the near-universal reaction of North American junketers there: The massive structuring BRT is really impressive in the numbers it carries, but hey, this is the developing world. Not only is car ownership low but it’s more authoritarian in its politics, giving mayors the power to effect massive transformation fast without much consultation. What’s more, these massive busways are effective but really unpleasant as urban design – not something I’d want in my city. Respecting the effectiveness and utility of the Bogotà busways, Grescoe does endorse Bus Rapid Transit in secondary corridors, but he has not seen busways done completely for a developed-world audience.

North Americans who want to experience successful Bus Rapid Transit in a developed-world context should skip South America and visit Brisbane, Australia, where a wealthy modern city moves, in part, on a complete network of beautifully designed, landscaped, and highly functional busways that flow into an underground segment right through the heart of downtown, and that are designed to provide an extremely frequent rapid-transit experience. There are some European pieces of good busway, such as Amsterdam’s Zuidtangent. But you have to go to Brisbane to see an uncompromised developed-world busway network, one that provides reliable operations end to end.

While Straphanger’s flirtation with anti-bus stereotypes was troubling to me, there’s a limit to how much Grescoe can be criticized for this. This is journalism of its time, and the bus=loser stereotype is still of our time in some cities. It’s up to each of us to decide whether to seek experiences that confirm our stereotypes or those that might contradict them, but nobody can challenge all of their stereotypes at once. Grescoe does eagerly challenge many other destructive attitudes throughout the book, and the brilliance of a book lies in the way it brings delight and confidence to the experience of both using and advocating transit and great urbanism. I heartily recommend this fun, enlightening, and inspiring read.

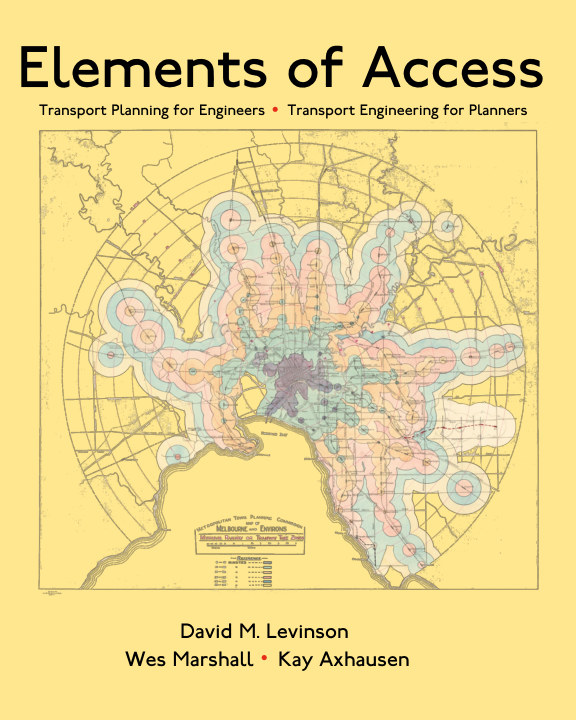

Access — where can you get to soon? — is, or should be, the core idea of transportation planning. David Levinson has long been one of the leaders in quantifying and analyzing access, and this work kicks off this fine new book. The cover — a 1925 map showing travel times to the centre of Melbourne, Australia — captures the universality of the idea. Access is what I prefer to call freedom: Where you can go determines what you can do, so access is about literally everything that matters to us once we step out our front door.

Access — where can you get to soon? — is, or should be, the core idea of transportation planning. David Levinson has long been one of the leaders in quantifying and analyzing access, and this work kicks off this fine new book. The cover — a 1925 map showing travel times to the centre of Melbourne, Australia — captures the universality of the idea. Access is what I prefer to call freedom: Where you can go determines what you can do, so access is about literally everything that matters to us once we step out our front door.