Blaise Pascal knew he was dying. He was in his 30s and had been sick most of his life, but at least he didn’t have to worry about being forgotten. He had already made transformative innovations in mathematics, physics, philosophy, and theology, and in his spare time he was assembling a collection of thoughts about God that would become the Pensées, which has been praised as some of the finest prose ever written in the French language. He was fortunate to live at a time (the mid-1600s) when, if you were born to the right parents, nobody told you you needed to specialize.

So what did he do with the last lucid days of his life? He invented fixed route public transport.

The vehicle used by Pascal’s service. Note that each had a fixed sign advertising the endpoints of the route. But who cares about the vehicle? What matters is the service. Source: Taras Grescoe’s Substack.

Wikipedia currently says he invented the bus line, but that’s too narrow. Pascal’s network, which he called carrosses a cinq sols or “five penny carriages” used eight-passenger horse-drawn carriages, but they did what fixed route public transport does. They operated predictable frequencies along multiple connecting routes, forming a network. This is not just the ancestor of every city bus, but also of every train or tram.

Had this really not been done before? Apparently not on land. Ferries are an ancient idea, both for crossing water bodies and for traveling along them. They are fixed routes, of course, but that’s mostly because the shore is fixed. Pascal’s idea was that even though carriages could go from anywhere to anywhere on Paris’s street network, a special kind of usefulness would arise if they didn’t do that, but instead followed paths that people could remember and plan around.

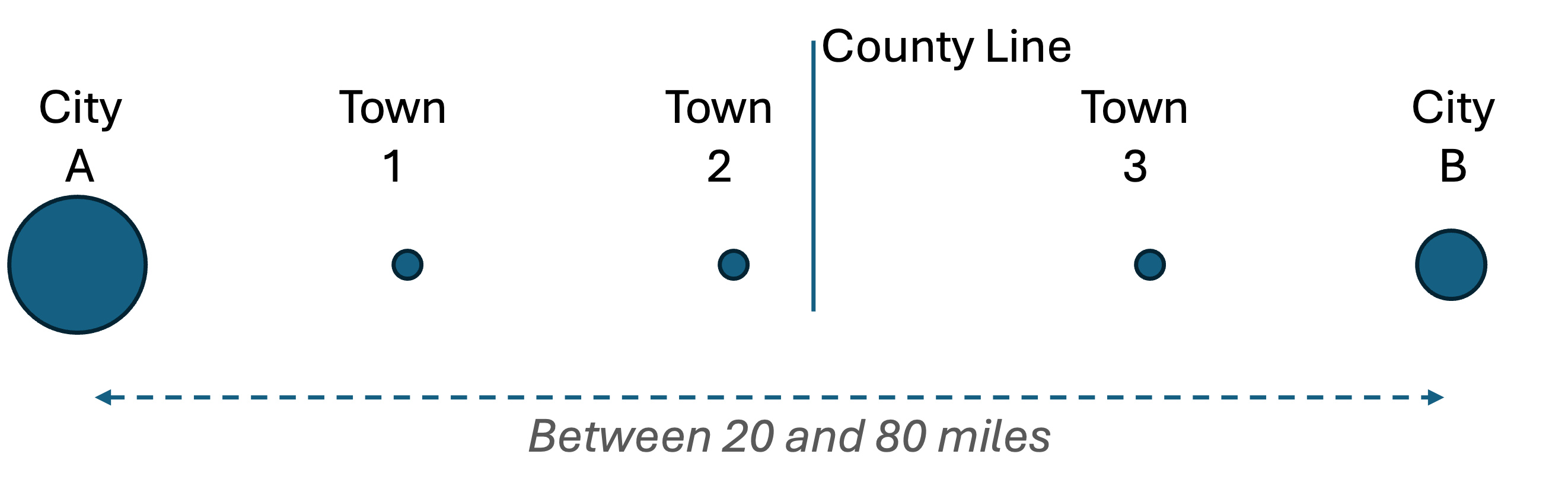

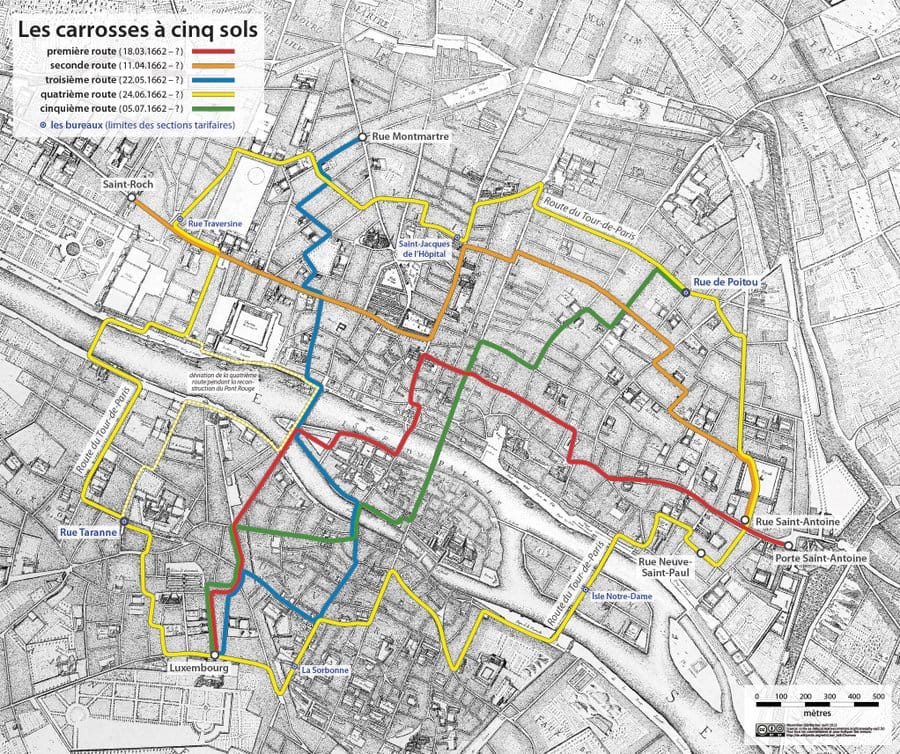

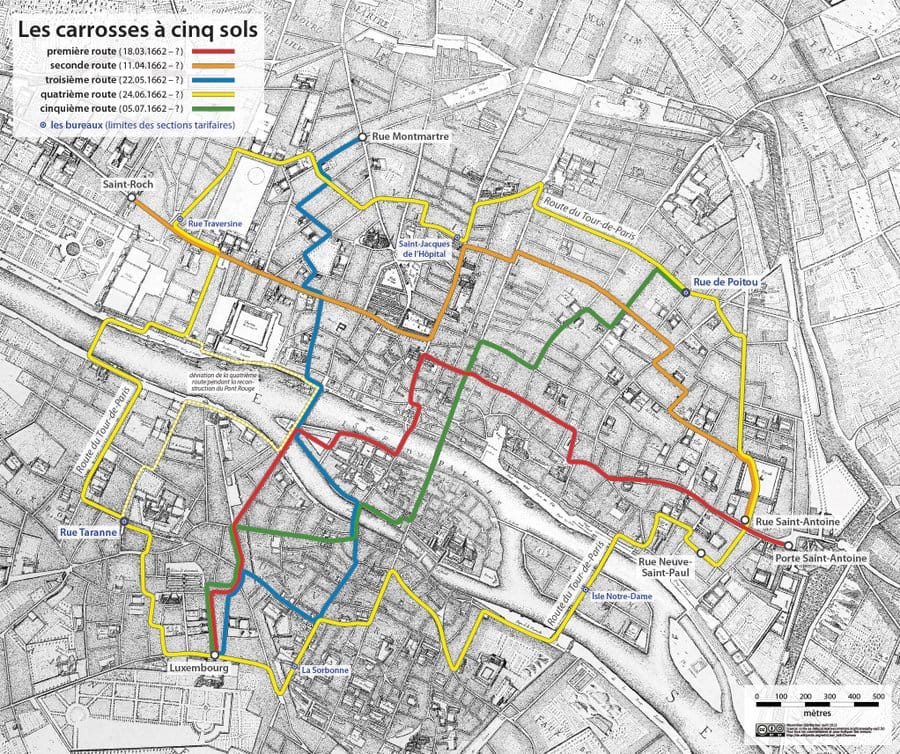

Here is the map of his complete network design:

Frequency ranged from 7.5 minutes to 15 minutes, so these came often enough that people could just go out and wait for them, not worrying about a schedule. Their main failure was overcrowding and pass-ups, which of course is a kind of success. Obviously, someone needed to invent a larger horse-drawn vehicle for this purpose, but that would wait a while still. The first line began on March 18, 1662 and the whole network was operating by July, just before Pascal’s death, a pace of implementation that is hard to imagine today. It’s likely that Pascal spent many of his final days thinking about this, when he wasn’t writing immortal prose about God.

If you want to trace the history of public transport from its roots in Pascal’s invention, please read this beautiful piece by the transit-obsessed travel and food writer Taras Grescoe. Here, I want to go a little deeper into understanding what this service was.

Gazing at the map, I recognize many of the eternal principles of fixed route transit planning: The lines try to remain far from each other, converging only on major destinations. They are often perpendicular, which maximizes the odds that a connection between those routes will make lots of trips possible. There are more or less straight lines running across the city — because where demand is spread uniformly, a straight line is more likely to match people’s desires than a winding one — and there’s an orbital line, yellow on the map that goes all the way around the edge in a two way loop. Orbitals are a common shape because they make such effective connections with radial lines, and their length means they connect an unusual number of origins and destinations directly.

At age 11, Pascal had re-derived much of Euclid’s geometry from scratch because his father kept the books from him, thinking he was still too young. So, dying at 38, Pascal probably could sense that these principles were mathematically right, even though they’d never been written down before.

But as a network designer I wanted to know more. How did this map come about? Did Pascal ever explain the design himself? What explains the biggest exceptions to the principles? The routes aren’t as straight as they could be. And why do so many of the lines converge at Luxembourg Palace in the southwest? Much of the government was around there, but still, was that really such a hub of citywide demand? I asked this question in English and French on both X and Bluesky, but I am not plugged into the French Enlightenment Transport History networks that must be out there, and most of Pascal’s biographers didn’t think this invention merited much discussion. I did find this French article by Rémi Mathis[1] which shares some speculations. (My loose translation.)

The first route [red on the map above] leads from Rue Saint-Antoine to Luxembourg, serving the Châtelet, the Île de la Cité and the Saint-Germain fair: it is clearly aimed at the bourgeoisie and la petite robe …and one will notice too that the routing links Pascal’s house with that of [his close friend and collaborator] Roannez while passing by that of the Arnauld family [close friends and the leaders of the abbey where Pascal’s sister lived].

A second and third route soon opened. They had to re-sequence their priorities when the king asked if there could be a route passing through the Louvre [presumably the orange line above]. The public mobbed the services to the point that often, several would pass by before there was room to board. Attempts were then made to take advantage of this influx of customers: “The merchants of the rue Saint-Denis are asking for a road with such insistence that they even talk of submitting a request [presumably to the king] for one.”

Finally, in order to connect the routes together and allow connections with the whole city, the fourth route [yellow on map above], opened on June 24, 1662, was circular.

Now, this sounds very much like how you might think bus network planning is done, if you just follow journalism about it: It’s easy to assume that key leaders first look after themselves, connecting their own homes and destinations.[2] Then, various powerful interest groups ask for a route, and the strong temptation is to draw a separate route for each of them. Finally the local equivalent of royalty get involved, “asking” in ways that everyone understands to be a command. This story is sometimes partly true in my experience, but tends to be exaggerated. Many journalists are rewarded for making people angry about the selfishness of the powerful, so they tend to emphasize that aspect of the process. You might not even know that, if your community is lucky, some smart planners are actually thinking hard about how to serve the whole city well.

Pascal was one of those smart people. His network design is much more logical than many of the networks I’ve seen that grew through the selfish demands of the few. He’s running the fewest possible route miles to sustain the highest possible frequency, for example, rather than letting routes “fray” into infrequent variants in order to get closer to more important people. On his map, the L-shaped red line, the first to be opened, looks rather political, but the rest all roughly fit the pattern of a network of radials and orbitals, designed to connect well with each other and thus maximize the number of origins and destinations connected in a reasonable travel time.

The fare, which was part of the service’s name, was intended to be affordable to a broad midsection of the Parisian social and economic scale. Obviously, urban elites continued to hire carriages just for themselves, just as they grab an Uber for all their trips now. But for the rest of the population, the only option had been to walk long distances across the city, often on muddy or icy streets whose poor maintenance and informal sanitation functions are barely imaginable to us today.

It worked. It wasn’t just popular, but it achieved a degree of social mixing that characterizes all large-scale public transport. One commentator notes that some relatively fortunate people still chose them:

Sauval, historian of Paris, states that “everyone after all, for two years, found these carriages so convenient that auditors and masters of accounts, advisers at the Châtelet and the court had no difficulty in using them to come to the Châtelet and the Palace”

Here is another distant echo of a pattern from today: Government employees are more likely to use public transport than private sector employees. But more generally, a service designed to be efficient and thus affordable will attract a diversity of riders, including many who don’t really need the fare to be that cheap. As a result, public transport, then as now, is a place where classes mix, and find no reason to be fearful of each other.

Again, read Taras Grescoe’s fine piece on the full legacy of Pascal’s invention. Today, I just wanted to share my incomplete probings on the network design. I will update this post if I learn more. Meanwhile, if you know anyone who is likely to know more about this, please share this with them.

[1] Hat tip to Emmanuel Marin, who writes the blog Sortir de Paris à velo (Getting out of Paris on a bicycle).

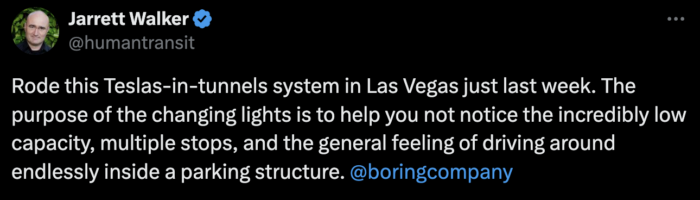

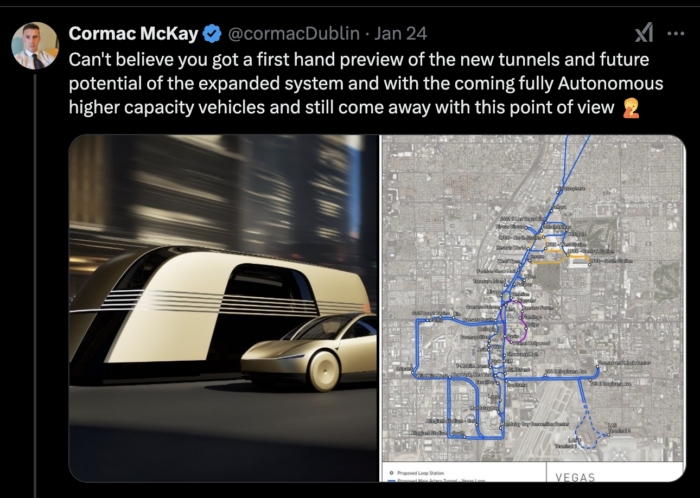

[2] For example, when Elon Musk was trying to promote his Boring Company car tunnels in Los Angeles, his first idea for a corridor extended from near his home in Bel Air to near his office in Inglewood.