by Christopher Yuen

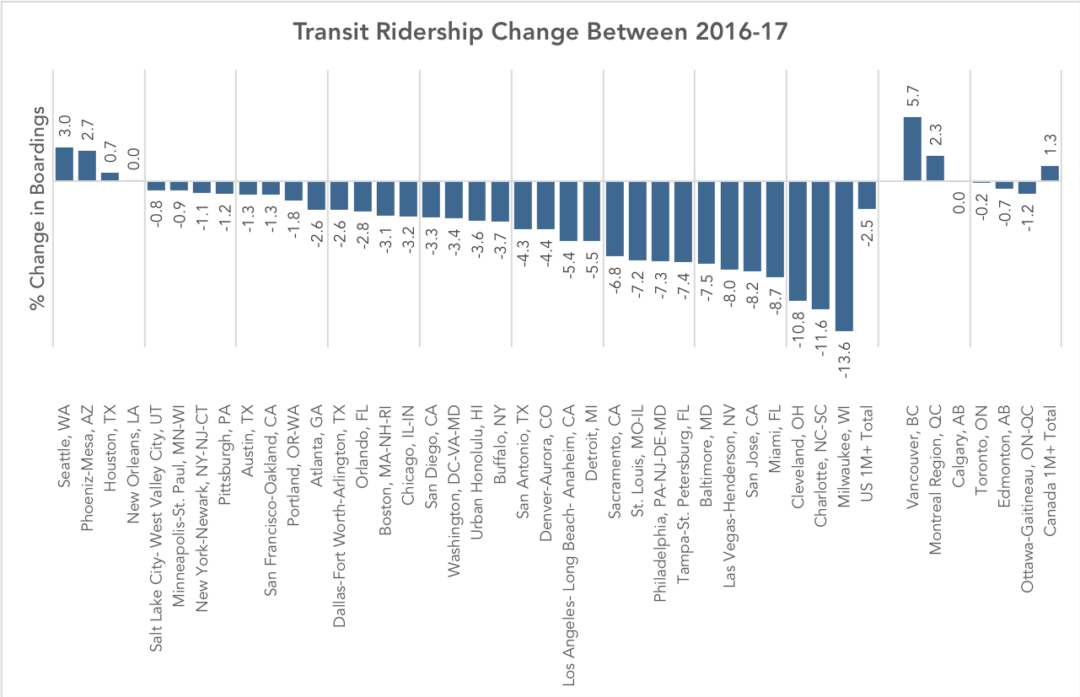

With only a handful of exceptions, transit ridership has stagnated or been falling throughout the US in 2017. The causes of this slump have been unclear but some theories suggest low fuel prices, a growing economy fueling increased car ownership, and the increasing prevalence of ride-hailing services are the cause.

A few North American agencies have bucked the trend, including Seattle, Phoenix, Houston, and Montreal. By far the biggest growth was at Vancouver, BC’s Translink, which saw a ridership growth of 5.7 percent in 2017.

But notice the big picture: In a year when urban transit ridership fell overall in the US, it rose in Canada.

Transit ridership urban areas with populations of over 1M are included in this chart. Ridership of major agencies that serve the same region are added together. (Source: National Transit Database; APTA 2017 Q4 Ridership Report)

There are three interesting stories to note here.

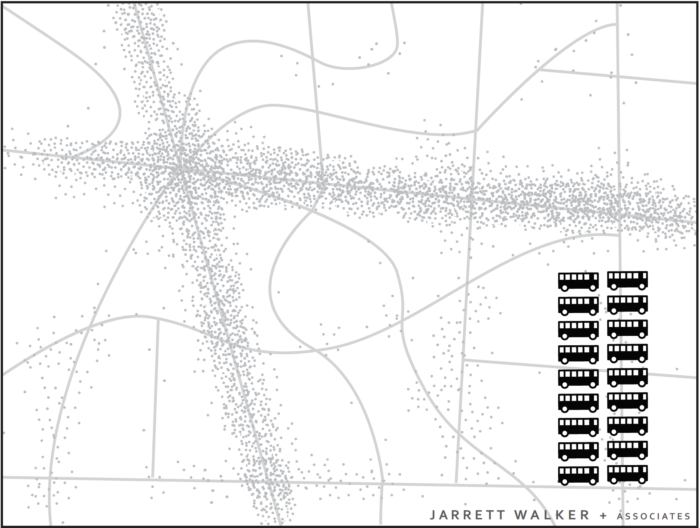

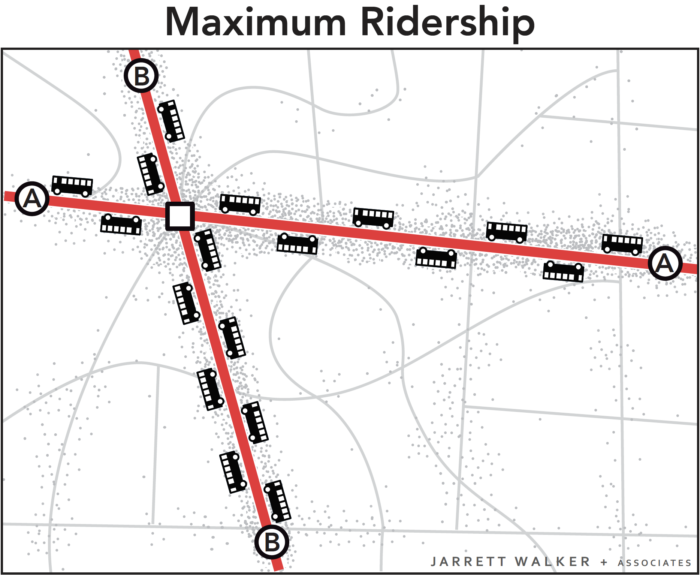

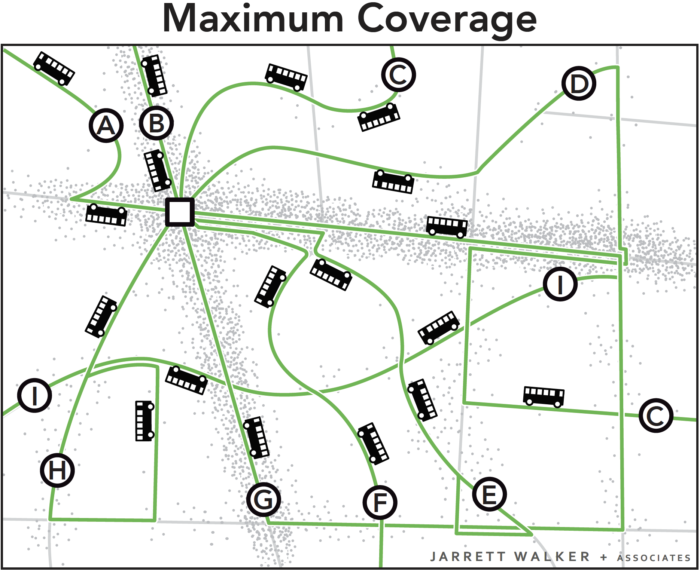

1. If You Run More Service, You Get More Riders

Canadian ridership among metro areas with populations beyond one million is up about 1.3% while regions of the same size in the US saw an overall ridership decrease of about 2.5% in 2017 despite the broad similarity of the countries and their urban forms. Why? Canadian cities just have more service per capita than the most comparable US cities. This results in transit networks that remain more broadly useful in the face of competition from other modes. Note, too, that Canadian transit isn’t cuter, sexier, or more “demand responsive” than transit in the US. There is simply more of it, so more people ride, so transit is more deeply imbedded in the culture and politics.

2. Vancouver Shows the Effect of Network Growth, Higher Gas Prices, Great Land Use Policy, and No Uber/Lyft

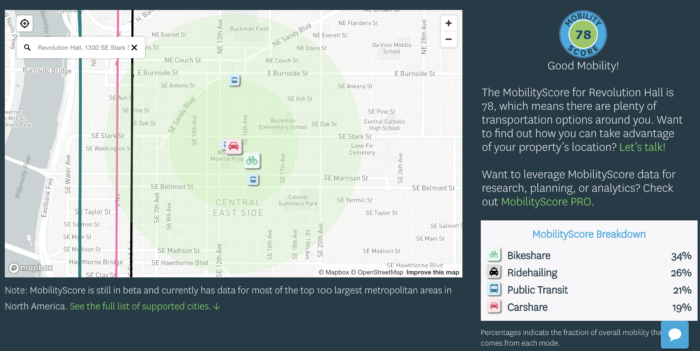

Vancouver’s transit ridership has historically been higher than many comparable regions as a result of decades of transit-friendly land-use and transportation policies, including an early regional goal to foster density only around the frequent network. (The Winter Olympics also had a remarkable impact: ridership exploded in 2010, the year of the Olympic games, but then didn’t fall back after the games were over; apparently, many people’s temporary lifestyle changes became permanent.) By North American standards, Vancouver is remarkable in the degree to which development is massed around transit stations.

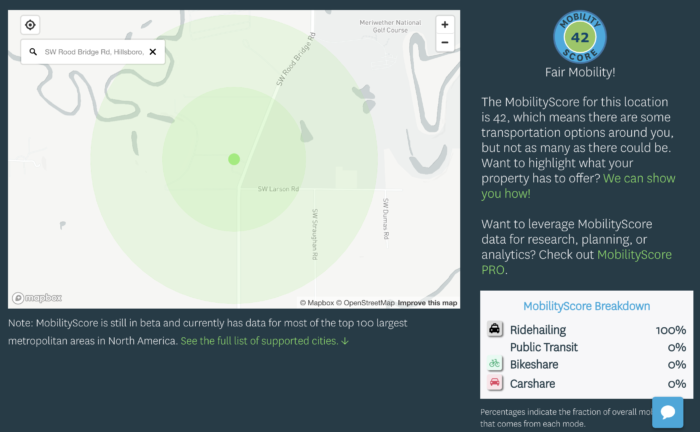

But Translink attributes its 2017 ridership growth to continued increases in service, high fuel prices, and economic growth. The 11km (7mi) Millennium-line Evergreen Extension just opened prior to 2017, directly adding over 24,000 boardings a day. Fuel prices in Vancouver have also reached an all-time high, at $1.5 CAD / litre (4.4 USD/ gal), an anomaly in North America, although still lower than in Asia and Europe. Economic growth has also been consistent, with the region adding 75000 jobs in years 2016 and 17. Notably, ride-hailing services like Uber and Lyft are not available in Vancouver due to provincial legislation.

3. There is Conflicting Evidence on the Impacts of Economic Growth on Ridership

Many commentators suggest economic growth to be a factor of the 2017 trends in transit ridership but there seems to be two conflicting theories, with economic growth cited as both a cause ridership growth and a cause of ridership decline. The positive link is obvious- economic growth leads to more overall travel, some of which will be made by transit. Contrastingly, the negative link is based on the theory that increasing incomes allow for more people to afford cars. Both theories seem plausible, but for both to be true, the relative strength of each must differ between cities.

Most likely, economic growth in transit-oriented cities is good for ridership, and growth in car-oriented cities, which encourages greater car dependence and car-oriented development, is bad. This would explain the roaring success of Seattle, Vancouver, and Montreal, though it doesn’t explain why Houston and Phoenix are doing so well.

As North American cities work to reverse last year’s losses in ridership, they may best learn from Canada, and a select few American cities, to leverage economic growth for ridership growth.

Postscript by JW

For Americans, Canada is the world’s least foreign country. There are plenty of differences, but much of Canada looks a lot like much of the US, in terms of economic types, city sizes and ages, development patterns, and so on.

So why is Canada so far ahead on transit? All Americans should be asking this. Ask: Which Canadian city is most like my city, and why are its outcomes so different? We’ll have more on this soon.