English

Por los últimos 18 meses, hemos estado rediseñando la red de autobuses para la agencia de transporte público del Condado de Miami-Dade, Florida (MDT, por sus siglas en inglés) con el grupo local Transit Alliance. Según se estaba acabando la última fase de participación ciudadana, la pandemia llegó a los Estados Unidos, y como muchas otras agencias, MDT entró en estado de crisis. Por lo tanto, nuestro trabajo estuvo en pausa por cuatro meses.

Según progresó la pandemia, se hizo evidente que la agencia necesitaba más de una red de transporte público lista para implementar. Necesitaba un plan que se pueda adaptar a una variedad de futuros impredecibles. Nadie sabe cuanto va a durar la pandemia, o que impactos tendrá en el dinero que la agencia recibe mediante impuestos.

Por lo tanto, mientras terminábamos la nueva red, trabajamos con la agencia y Transit Alliance para desarrollar un Plan de Resiliencia para guiar la toma de decisiones en el futuro sobre como se debe aumentar o reducir el servicio.

Pero primero, vamos a hablar de como llegamos aquí.

En la primera fase del proyecto, desarrollamos un Informe de Opciones para analizar la red existente y discutir preguntas claves que determinan como se debe diseñar el sistema. Tomamos información del público y diseñamos dos redes conceptuales que señalan la diferencia entre enfocarse en cobertura o enfocarse en alta frecuencia. Tuvimos otra fase de participación ciudadana para preguntarle al público hacia donde se inclinan entre las dos redes conceptuales. Recuerda que nunca es uno o el otro; alta cobertura y alta frecuencia representan los dos extremos de un espectro. Basado en los comentarios del público, diseñamos un Plan Borrador entre los dos conceptos y ahora lo acabamos de revisar para hacer el Plan Final.

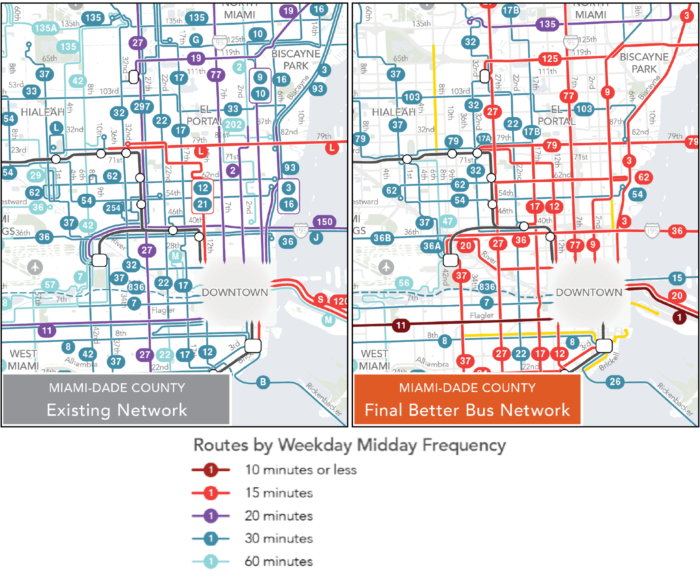

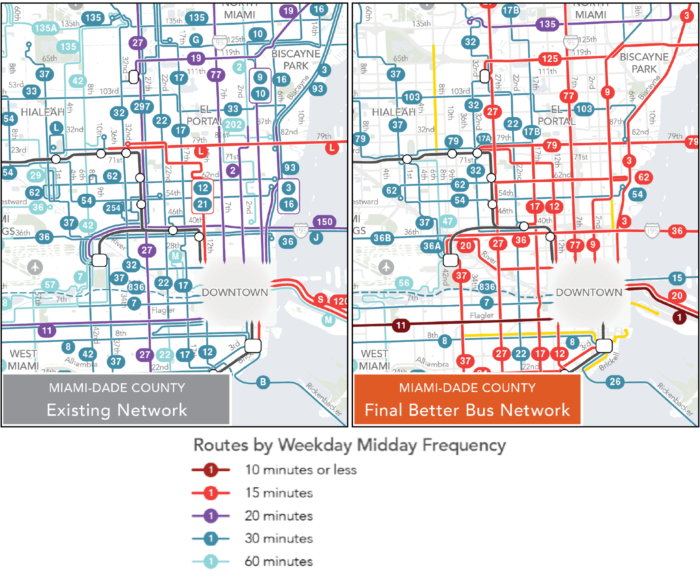

A continuación, hay trozos de la red existente y la nueva red en el centro de la región (haz clic abajo para ver cada mapa entero).

Una comparación de los mapas de la Red Existente y la Nueva Red en el Condado de Miami-Dade, Florida. Nota que los colores de las líneas indican la frecuencia a mediodía.

Haz clic aquí para ver el mapa completo de la Red Existente

Haz clic aquí para ver el mapa completo de la Nueva Red

El nuevo sistema crea una red frecuente que ayuda a los residentes llegar a más lugares en menos tiempo. Con esta red, 353,000 más residentes viven cerca de una ruta frecuente (un aumento de 13% sobre el sistema actual). Con la nueva red, el residente promedio puede llegar a 36% más trabajos en 45 minutos usando transporte público y caminando.

La red frecuente significa que es más fácil cambiar de rutas y llegar a muchos más lugares dentro un tiempo razonable. La animación a continuación muestra a donde una persona puede llegar en 45 minutos usando transporte público y caminando desde Liberty City (NW 12th Avenue y 62nd Street). La zona gris muestra a donde una persona puede llegar con el sistema existente y la zona azul clara muestra a donde se puede llegar con la nueva red. Con la nueva red, alguien que vive en Liberty City, puede llegar a 60% más trabajos y 50% más personas. A esto es que nos referimos cuando hablamos del acceso a oportunidad.

Este mapa muestra los lugares a donde se puede llegar desde Liberty City en 45 minutos usando la Red Existente y la Nueva Red.

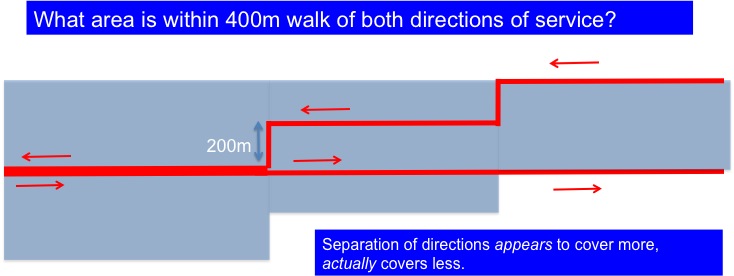

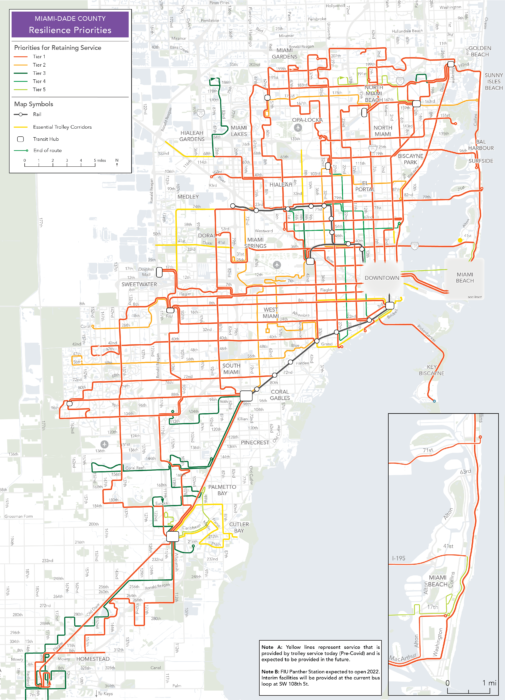

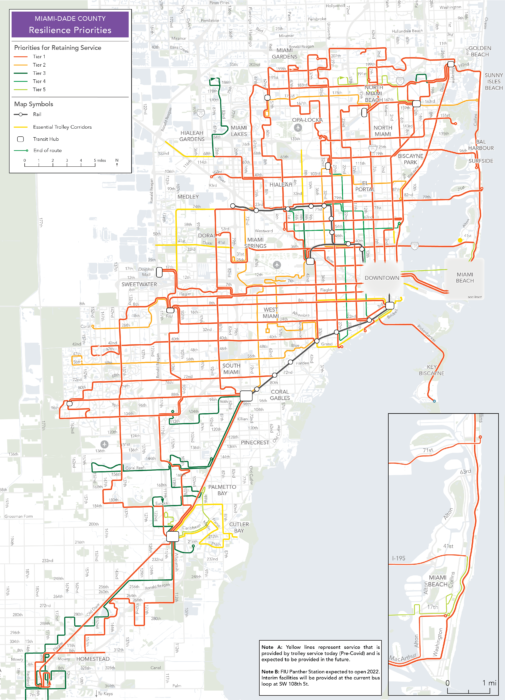

Esta amplia expansión en acceso solo es posible por la red frecuente. Esto significa que, si MDT tuviese menos dinero, pero quisiera maximizar el acceso de esta manera, tienen que proteger la red frecuente. Eso es lo que hace el Plan de Resiliencia. Los corredores del sistema están divididos en niveles para establecer que servicio se debe operar bajo diferentes niveles de fondos.

El Plan de Resiliencia protege la red frecuente en caso de una disminución de fondos.

En el nivel económico más grave (Nivel 1), la red solo sigue operando corredores frecuentes cada 1.6km (una milla en la cuadrícula vial de Miami) y algunas rutas de cobertura que son críticas para asegurar acceso equitativo. Sí, esta red hará que la gente camine distancias más largas. Pero cuando lleguen a una ruta, el autobús siempre viene pronto. Si MDT tiene más fondos, puede añadir el servicio del Nivel 2 y así sucesivamente.

Nadie quiere ver esta reducción de servicio, pero si fuese necesario, MDT podrá minimizar el daño al acceso a oportunidades usando el Plan de Resiliencia. Por el otro lado, si MDT decide recortar servicio como se suele hacer – manteniendo todas las rutas con menos frecuencia – el acceso a oportunidad se reducirá drásticamente. Consolidar rutas para hacerlas más frecuentes puede hacer que los viajes sean más cortos, aunque haya que caminar más.

Esta red final ahora esta en las manos de la Comisión del Condado para endosarlo, y si lo aprueban, será implementado por MDT. Probablemente habrá más oportunidades para comentar sobre este plan antes de que se implemente. Si viven en Miami-Dade County, recuerda someter un comentario o decirle a tu Comisionado sobre este Plan, especialmente si te gusta. Lamentablemente, la mayoría de los comentarios público sobre planes de transporte público son negativos incluso si a la mayoría de la gente le gusta el plan, porque la gente falsamente asume que se implementará como sea. Este plan no se implementará si no atrae mucho apoyo positivo. MDT quisiera comentarios constructivos sobre el plan, que se usarán para hacer que la implementación final sea aún mejor. Pero si te gusta el plan, ¡es importante que lo digas también!